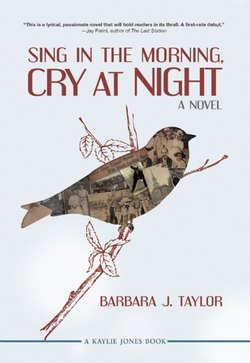

Читать книгу Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night - Barbara J. Taylor - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER EIGHT

OWEN SAT IN FRONT OF BURKE’S, where he rented a furnished room by the week, balancing his beer-filled growler on one knee. He could see the pink edges of daybreak above the black culm banks as he watched for Tommy Davies. In the month since he’d left home, he’d started meeting the boy at the square, so they could walk to work together.

Owen had started carrying beer in his lunch pail, but only so he’d have something to drink at the end of his shift, when the pain became unbearable. He knew the mine held countless dangers and alcohol only added to them. No telling how a man might meet his end. Burned, suffocated, drowned, buried under tons of coal. Roof squeezes happened often enough. Sometimes a man miscalculated the number of pillars needed to support the ceiling in a gangway or chamber. Other times, a roof fell in spite of the properly spaced columns of coal. The odds of a squeeze always increased when their bosses ordered them to “rob the pillars” after a mine had been worked to its limit. Countless times, Owen had been sent to some back chamber to take as much coal from the pillars as possible. Like all the other miners, he knew the practice was illegal and could cause a collapse, but he also knew that speaking up would get him fired.

The stories of fallen miners always made several passes through town, offering information to satisfy each listener. The women usually focused on the tragic loss. He was someone’s husband, son, or brother. The miners pored over the grisly details. Was he intact? Did he have all his limbs? Was the face recognizable? That’s why they wore those round metal tags each time they stepped foot in a mine. Often, a man could only be identified by the number pressed into the center of the oversized coin.

Everyone who heard the stories listened for a mention of last words. Such remarks seemed to bring comfort to the listener. They suggested the miner had not died alone.

“Morning,” Tommy said as he crossed the street.

Owen nodded his greeting as he stood. “How’s everything next door? Grace still letting you fill the coal pails for her?”

“Yes sir.” Tommy studied his feet as he spoke. “Most days.”

Owen could hear discomfort in the boy’s voice. His mother, Louise, had surely sided with Grace, as well she should. She’d probably instructed her son not to answer any questions Owen might ask about his wife and daughter. Let him come home and find out for himself, he could hear her saying. Nonetheless, Tommy was his only connection to Grace at the moment, so he continued: “And you’re tending to the ashes?”

“As best I can. Don’t see her around much, though,” he added in anticipation of Owen’s next question, the same questions every day.

“And Violet?”

“Don’t see much of her, either. Probably inside with Mrs. Morgan,” he reasoned.

“I trust you’ll tell me if something needs doing around the place.”

“Yes sir.”

Owen decided not to press the boy further. The two turned the corner in silence and plodded toward the colliery.

Although men had been working this part of the Sherman for better than fifteen years, folks still referred to it as the “new mine.” Long before George Sherman was born, his father Oskar had opened a slope mine on the land. Men blasted and picked their way through eight chambers in about as many years before exhausting most of the resources. Engineers knew that rich veins of anthracite lay far below the mine’s floor, and by then, excavation methods had improved enough to get at them. Oskar Sherman had two choices: convert the existing mine into a vertical one with multiple underground levels, or dig a companion mine adjacent to the old one. Since the slope mine still had about a year’s worth of anthracite left in its walls, he instructed his engineers to blast alongside the existing operation. His decision proved to be a lucrative one. Between mining the walls and robbing the pillars, his men had enough work to see them through the colliery’s expansion, and they brought in enough money to pay for it.

Tommy stopped at the above-ground stable. “Be needing some salve for one of the mules. His harness keeps chafing.”

Owen nodded goodbye and continued on to the mine’s entrance.

A dozen men stepped into the cage and, after a signal of two whistles, were lowered into the mine to begin a twelve-hour shift. Owen pegged in with the fire boss where he received his assignment: continue driving the new gangway on the fourth level. After adjusting the flame in his lamp, he fingered for luck the numbers 1-9-4 on his metal tag and waited for the other men to pass by. Like every morning these days, Owen walked the rail alone, and remembered.

* * *

He knew he should have stepped inside the moment he heard the squabble in the kitchen, but he’d figured Grace could handle it this one time. After all, she seemed to be in better spirits lately, and a man deserved an hour of leisure now and again. Owen required no other holiday than a pipe, a copy of the Scranton Truth newspaper, and his rocker on the porch. Unlike most folks, he reveled in the scorching Fourth of July sun. He liked weather in all its forms. Hot, cold, rain, snow, no matter. Variety. Outdoors. Life. The coal mine was another story. Stagnant air, sunless hours, a constant temperature of fifty degrees. An underground womb stripped of its soul. Owen thought himself fortunate to have had daughters. The mine might support his children, but it would not claim them.

He stood up and called through the front door, “Everything all right in there?” Silence after a ruckus always alarmed him. Owen stepped into the kitchen and found Grace sprawled on the floor in a huckleberry puddle. He eyed each girl to determine the course of events. Daisy stood not two feet away, her white dress speckled in purple. Violet hung near the door.

“Now look what you’ve done,” he directed at Daisy for no other reason than proximity. He squatted down next to Grace, pushed errant wisps of hair in the direction of her bun, and lifted her off the floor. “And don’t think you’re excused,” he said to Violet. “This has your hand all over it. Moping all morning. Nothing more disappointing than a jealous child.”

“Hooligans, the pair of you.” Grace twisted the back of her long skirt around front to inspect the damage. “Ruined.”

“It’s her fault.” Daisy pointed at her sister. “She started it.”

“Not another word, young lady.” Owen scooped the berries into the dustbin. “I expected more out of you. Your mother working so hard to make the day nice, and what do you do? Ungrateful, that’s what I say.”

Tears welled in Daisy’s eyes, and Owen immediately regretted his impatience. Words of apology circled his mouth, but reprimand fell into line ahead of them. “Outside, both of you, while you still can.”

That was the moment he couldn’t bear. The shame of it consumed him. The last time he’d ever see his daughter whole, and he’d turned away from her to tend to Grace. “Let’s get you cleaned up,” was all he’d said as he guided his wife toward their bedroom.

* * *

Up ahead in the mine, Owen heard Davyd Leas, one of the elders from Providence Christian, leading some of the men in prayer as he did every morning before they started their shift in earnest.

“Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death . . .”

Owen walked past the men and onto the gangway, refusing to acknowledge any God who would take his child.