Читать книгу Jack's Book - Barry Gifford - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

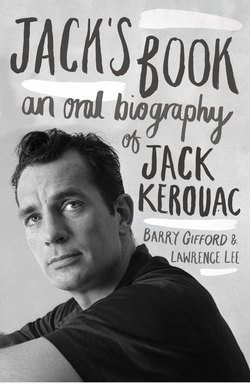

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION TO THE NEW EDITION

by Barry Gifford

On May 30, 1936, in a letter to Arnold Zweig, Sigmund Freud wrote: “To be a biographer, you must tie yourself up in lies, concealments, hypocrisies, false colorings, and even in hiding a lack of understanding, for biographical truth is not to be had, and if it were to be had, we could not use it. . . . Truth is not feasible, mankind doesn’t deserve it. . . .”

Heeding Freud’s admonition, Larry Lee and I chose the rather unorthodox (for that time, 1975) method of “oral history” to capture on record the brief life of Jack Kerouac. Larry called it “a rather more immediate form of biography”; the idea being that since most of Kerouac’s cronies and family members were still alive (he having died of alcoholism at the early age of forty-seven), if we could find and then persuade them to talk candidly about the subject, it would be left to us—and the reader—to sort through the revisionism and decide whose versions most closely approximated the ineluctable “truth.” It was Jack’s longtime cohort, the poet Allen Ginsberg, who pronounced, upon completion of his reading of the uncorrected galleys of the book: “My god, it’s just like Rashomon—everybody lies and the truth comes out!” Allen’s words are branded in my memory; I am not paraphrasing.

It was Allen’s well-meaning desire to see Kerouac presented in the “best” light, owing, no doubt, to the disrespect and disservice that Jack—and Allen, among other contemporaries—had received from critics and the news media during the heyday of the “Beat Generation.” Though Jack’s Book surely presents Kerouac warts and all, it was Larry Lee’s and my intention to get people busy reading JK’s eleven mostly ignored novels and other works. When we began our research for this biography, only three of Kerouac’s books were in print: On the Road, The Dharma Bums, and Book of Dreams. By 1980, two years after the publication of Jack’s Book, at least eight titles were available. In 2012, virtually all of Kerouac’s work can be found in new editions, films of his novels On the Road and Big Sur have been made, and he has become something of an industry.

Larry and I did not intend that Jack’s Book be a “definitive” study. We assumed that more scholarly approaches would follow ours—“Après moi,” wrote JK, “le deluge”—and, true enough, that avalanche fell in short order. In fact, it’s still falling. We wanted to create a conversational, novelistic (in terms of dialogue) reckoning of this man’s life. We wanted the people he knew and loved and hated, and who knew and loved and hated him, to say whatever they had to say without being given too much time, too many years, to think about it. In most cases, these people had not yet spoken on the record about Jack Kerouac. Their thoughts were fresh—they didn’t know what they thought until they’d told us, until they’d said it out loud. One reviewer declared, “If you’re interested in listening to what the talk of the fifties sounded like, and if you believe that literature may just have something to do with life, then read this book.” That was what we were after, the talk.

The novelist and journalist Dan Wakefield, later to himself chronicle the period in his memoir, New York in the 50s, magnanimously described our effort as “a fascinating literary and historical document, the most insightful look at the beat generation.” The key word there, for us, is document. Jack’s Book is constructed like a documentary, what Kerouac, in his novel Doctor Sax, called a “bookmovie.” Others of Mr. Wakefield’s generation decried the new attention being paid to Kerouac; they had disliked him and/or his work then, and they disliked him and it—and, by association, Larry Lee and me—now. That was all right with us; we, who cared enough about his writing to devote two years of our lives in an effort to get the Kerouac ball rolling again, expected as much.

We knew that just the mention of the name Jack Kerouac was enough to aggravate some people. We also knew that his novels had inspired thousands and thousands of readers—especially youthful readers—to get the hell out of whatever boring or dead-end situation they were in and take a chance with their lives. I’ll always respect the writer Thomas McGuane for going on record about JK, saying in an essay that he, McGuane, never wanted to hear a word against Kerouac because Jack had indeed worked a kind of salutary magic on more than a few. “He trained us in the epic idea that . . . you didn’t necessarily have to take it in Dipstick, Ohio, forever,” McGuane wrote. “Kerouac set me out there with my own key to the highway.” Kerouac’s literary standing aside, the man had the power to move others.

Jack Kerouac was no avatar and Jack’s Book was not meant as hagiography. This book—biography, reportage, collage, holy mosaic, unholy mess, however it’s been and will be characterized—contains some extremely emotional, confessional material; it’s not dull. Dr. Freud notwithstanding, there is at least a sort of truth to be found here. The book belongs to those persons who bared their souls in conversations with us about their dead friend or adversary. Therefore, it belongs to Kerouac, which is why I titled it Jack’s Book. These are letters to a dead man from people who for one reason or another didn’t tell him what they really thought of and about him while he was alive. It was Larry’s and my pleasure to provide them the belated opportunity.

I’ll never forget sitting with Jimmy Holmes, the hunchbacked pool-shark of Denver, in the stuffy parlor of his elderly aunt’s apartment, where he lived, and him saying to me, after I’d read aloud a lyrical passage from Visions of Cody that Kerouac had based on his life, and which Holmes had never read, “I didn’t know Jack cared about me that way. He really cared, didn’t he?” Or stumbling drunkenly along the Bowery in the wee hours one frozen February morning with Lucien Carr, who kept repeating, “I loved that man. I loved Jack, goddam it, and I never told him!”

This new edition is lovingly dedicated to the memory of Lawrence Lee, who died on April 5, 1990.

—BG, 2012