Читать книгу Jack's Book - Barry Gifford - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

America makes odd demands of its fiction writers. Their art alone won’t do. We expect them to provide us with social stencils, an expectation so firm that we often judge their lives instead of their works. If they declare themselves a formal movement or stand up together as a generation, we are pleased, because this simplifies the use we plan to make of them. If they oblige us with a manifesto, it is enforced with the weight of contract.

So it happens that, from Henry James on, Europe is regarded by Americans as a large lending-library of inspiration, and expatriation becomes something of a duty, whether fulfilled or not. Ernest Hemingway makes a market for wineskins. Mr. and Mrs. Scott Fitzgerald certify a dip in the Plaza Fountain as apt behavior for young Americans of a certain class and time.

Having derived an etiquette from their works, we hold these writers in our minds as creatures of the moment in which we noticed them. If they abandon our expectations, the literary critics and chroniclers put them in their place, like stamps that have been stuck onto the wrong page of the album. In this way we sometimes deny artists the ordinary chances at growth and change that are among art’s bare necessities.

This book is about a man who was a victim of this spirit of literary utilitarianism. Jack Kerouac is remembered as the exemplar of “the Beat Generation.” But the Beat Generation was no generation at all. The label was invented as an essay in self-explanation when journalists asked questions, but it was accepted at face value. Kerouac used the phrase above one of the first samples of On the Road to reach print (“Jazz of the Beat Generation,” 1955) and his friend John Clellon Holmes, who had described the same world in his novel Go, obliged the New York Times Magazine and Esquire with think-pieces about this new generation written in the style that the readers of those journals expected.

Kerouac was a writer whose belated success depended upon a new prose method, which he applied to a sturdy old form, a young man’s varied adventures. It was Kerouac’s misfortune that his fame—as distinct from his literary standing, a matter yet to be determined—owed more to the people and events he portrayed than to the way in which he portrayed them, as he later insisted he would have preferred.

Cutting away the amateurs, the opportunists, and the figures whose generational identification was fleeting or less than wholehearted on their own part, the Beat Generation—as a literary school—pretty much amounts to Kerouac and his friends William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. In life and in art the three relied upon one another in strong and complex ways, and, more than four decades after his death, Kerouac’s prose style lives on in the forms Ginsberg adopted to become the world-poetry voice he is today. Ginsberg shed his role as the earnest, necktie-wearing “Ginsy” of the 1940s and managed to utilize the dangerous energy of publicity in projecting an image useful to his motives as a poet. Burroughs, whose frosty distance and Coolidge-like silences evidently have been in his repertoire since boyhood, saw to it that he was left alone. A fourth figure, Gregory Corso, entered the circle late, and continues to play the poètemaudit, lately in France, where that role is a matter of accepted tradition. Kerouac’s failure to adopt any of his former cohorts’ survival tactics or to find a successful one of his own is the sad heart of the last part of this book.

When On the Road appeared in 1957, after languishing in Kerouac’s rucksack for years, Jack won the literary and commercial success he had wanted desperately, but had failed to achieve with his first novel, The Town and the City, published in 1950. Ginsberg asked him to write a brief explanation of his technique, and it was printed in The Black Mountain Review, the journal of that resolutely advanced Southern college, as “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose.” Kerouac’s method was a war on craft, but his notes were adopted as the excuse for a torrent of bad stream-of-consciousness prose and poetry. Kerouac, unwillingly, was set up as the avatar of a movement that he had no desire and little ability to advance. Suddenly, he found himself placed by the media at the center of a stage dressed with props from French existentialism (black sweaters, berets), late romanticism (footloose hedonism) and the whole race-hoard of ideas about drugs, from De Quincey to Anslinger.

Kerouac realized the threat of this role at once, but he reacted with an odd mixture of shyness and belligerence. He accepted the attention, at first, as a compliment. Its focus was an insult. Why didn’t the journalists examine the books as well as the man? As he told The Paris Review in 1967:

I am so busy interviewing myself in my novels, and I have been so busy writing down these self-interviews, that I don’t see why I should draw breath in pain every year of the last ten years to repeat and repeat to everybody who interviews me what I’ve already explained in the books themselves. . . . It beggars sense.

He began to say forthright things about his essential conservatism and religiousness, and they were duly quoted with the feature-writer’s skill at synthetic irony. Esquire portrayed him as a pathetic class-traitor, a hipster-as-Bircher. Although that particular insult was delivered only after his death, Kerouac did live long enough to recognize the imminent fulfillment of this prophecy he had delivered in 1951 across a midnight kitchen table to Neal Cassady:

A Ritz Yale Club party where I went with a kid in a leather jacket, I was wearing one too, and there were hundreds of kids in leather jackets instead of big tuxedo Clancy millionaires . . . cool, and everybody was smoking marijuana, wailing a new decade in one wild crowd.

He saw it coming before anyone else, and he got blamed for its coming at all.

This confusion between some of the social forms of the late sixties and the content of Kerouac’s work continues to do his reputation damage. In Exile’s Return, his book about the social side of American letters between the world wars, Malcolm Cowley describes The Saturday Evening Post’s thirty-year grudge against Greenwich Village, a vendetta replicated by the New York Times, which still maintains a specialist in critical attacks on “the Beats.” Students of English literature waited twenty years for the first scholarly edition of On the Road, and only in recent years has Kerouac’s work begun to prevail over what poet Jack Spicer called “the great, gray English Department of the skull.”

But despite the gap on the assigned-reading list, students at any school of a certain size, whether in Ann Arbor, Chapel Hill, Austin, or Cambridge, have always been able to step across the street and find a big selection of Kerouac novels, often in British paperback editions. The books live. On the Road has never gone out of print. Ginsberg and fellow poets have created a Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Buddhist college in Colorado, Naropa Institute. Movie companies are exploiting Kerouac’s novels again, and a play based on his life was produced in New York in 1976 and in Los Angeles in 1977.

As with Scott Fitzgerald, another drinking Catholic who gave out at the midpoint, there is a threat that Jack Kerouac’s legend may supplant his work, rather than merely overshadow it. Had he lived unto silvery literary senior-statesmanship, it is possible that one publisher or another would have fulfilled his wish for corrected and uniform publication (with the names straight, once and for all) of his “one vast book . . . an enormous comedy, like Proust’s.” He would have called it The Duluoz Legend. As it is, the one-vast-book notion cannot accommodate his first novel, The Town and the City, a fact Jack acknowledged. He would have set it aside. There are other problems. Tidy-minded publishers forced him to give the same characters exasperating strings of pseudonyms masking pseudonyms and even, in The Subterraneans, to disguise New York as San Francisco in a hedge against libel suits. His work is scattered among foreign and American houses, individual volumes popping in and out of print.

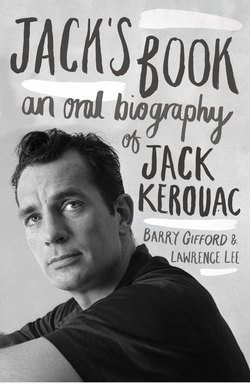

The idea of this book is to provide the framework for a first or fresh reading of Kerouac as a man who succeeded in giving us his one vast book, but in the bits and pieces the marketplace demanded. The authors are men born during or shortly after World War II who at first knew their subject only through his work, where they found the energy for the undertaking of learning as much as they could of his life.

Kerouac died in 1969 at the age of forty-seven, young in the terms of our time. Most of his friends survived him. Our idea was to seek them out and to talk with them about Jack’s life and their own lives. The final result, we hoped, would be a big, transcontinental conversation, complete with interruptions, contradictions, old grudges, and bright memories, all of them providing a reading of the man himself through the people he chose to populate his work.

The job took us back and forth across the country twice, mostly by airplane. The very roads have been replaced since Jack’s travels by the homogenized culture of the Interstate Highway system, but the people of Kerouac’s novels have survived. We talked to seventy or so individuals, thirty-five of whom speak here. We had no “Rosebud” to ask them about, like the friends and victims of Citizen Kane, nor, although more than one interviewee proposed the metaphor, did we feel much like the field investigators in the Roman Catholic Church’s saint-making procedures. Much of what we learned from these conversations has been used in the text that binds the excerpts from them together. We have let Kerouac’s friends speak a good deal about themselves because it seemed to us both possible and proper to provide a group portrait as well as a close-up of the man who stands at its center. Because the cast reached Russian-novel proportions, we provided the character key as an aid to following their appearances in this book and those of their fictional shadows in Kerouac’s.

In what follows you will read again and again, in many voices, that Kerouac’s novels were fiction, not reportage. We agree. It is fascinating to see the way in which real people, places, and events are utilized in the books, which then fed back to alter reality, but the technical leaps and the heartbreaking beauty of Kerouac’s prose take his novels into a realm far beyond that of the reporter or diarist. His books are the product of a genius at recollection. When he was a boy in Massachusetts Jack’s friends nicknamed him “Memory Babe.” To the editor who brought On the Road to light he was the recording angel. To his friend and fellow novelist, John Clellon Holmes, he was “the great rememberer.” And to a great many of those with whom we spoke, memories of Jack were mixed up with notions of sainthood. If miracles are required as evidence of his life, his books themselves should suffice.