Читать книгу Jog On - Bella Mackie - Страница 8

ОглавлениеI ran for three minutes today. In the dark, slowly, and not all in one go. That’s three minutes more than I’ve ever run in my life. I’m out of breath and I’ve got a stitch and I already feel better than I have in years. That’s enough for a first attempt. Now I can go back home and have a cry. Or some wine.

Even as I lay on the floor of my sitting room, watching my husband’s feet walking quickly towards the door, I was already thinking about what was to come. When a marriage breaks down, there will be unbearable sadness, awkward questions, sometimes embarrassment. I could imagine all of them. Staring down at the rug, my mind had jumped ahead, blurrily plotting out the impending future. I even started to vaguely compile the inevitable playlist of terrible songs that I knew would be belting out mournfully at 4 a.m. for weeks to come.

I have learnt now that the actual moment of heartbreak can be astonishingly brief. It’s not always the drawn-out disintegration you imagine it might be as an adult, bits of love and comfort slowly breaking off over years, until there’s nothing left to say at all. Sometimes it happens in a flash, takes you by surprise, gives you no time to prepare. Someone stands across from you, looks directly into your eyes and tells you that they are leaving you, that they no longer love you, that they have found someone else, that you are not enough, and you think: ‘Oh, so this is the moment that I am going to die. I can’t possibly get through this.’ Somewhere, something in your body has savagely ruptured, and all you can think to do is to lie down on the floor and wait to be invited to walk down the inevitable tunnel of light.

I don’t know which way is worse. Both are hideous, most break-ups are. I once heard a story about a couple in a restaurant who ate in total silence for over an hour. When coffee came, the husband whispered something to the wife, who hissed back: ‘It’s not the coffee, it’s the last twenty-five years.’ A slow crumbling like that would be pretty appalling. But when you’re given the surprise approach, the moment of impact feels brutally physical. Despite this shock, it’s also, weirdly, the easy bit. Because sooner or later, you realise that you’re not going to die. And you can’t even stare blankly at the carpet for too long because you have to pick up your kids from school, or walk the dog, or go to work. Maybe you just need to pee. Your pain doesn’t even stand up to the most mundane demands of an idle Monday. And after this unwelcome realisation, you see the future quite clearly: you’ll stumble through this moment. But it takes such a long time. Heartbreak is brief. The way out of it is interminable, and sometimes you resent even having to try.

Even as I lay there, I knew that I would shortly have to get up off the floor. I even knew that, with the right coping skills, it might be OK in the end. But I also knew something else. I knew that unlike most adults, I didn’t have any coping skills.

We learn to feel long before we learn how to make sense of those feelings. Babies laugh and cry, and get angry, yet can’t tell us why. But as we grow up, we develop the methods we need to help us deal with stressful or traumatic events. Our teenage years are often spent feeling frustrated and confused, but we eventually gain insight into ourselves, and we learn how to better deal with mature emotions. We take these tools with us into adulthood, where we refine them and grow to develop a clearer understanding of how to face our own personal challenges. At least, most of us do. But right up until the moment I found myself lying on the floor, I had spent a lifetime running away from my problems. Anxious even as a very small child, I had let my worries fester, take control, and dominate my life. Mental-health problems had stunted my own growth, leaving me too scared to take on challenges, trying to rigidly control the environment around me to prevent any possible hurt. Quitting things when they got hard. Turning down opportunities that would push me, or give me independence. Being small.

I got used to hiding my head in the sand from a young age, and using magical thinking to ward off bad things. Instead of recognising I was ill, I’d come up with ways to cope with my worries and irrational thoughts, none of them successful. I’d spit if I had a scary idea, or blink hard to expel it. I’d avoid certain numbers, letters, colours, songs and places. All as a way to ‘compromise’ with my brain, in the hopes that the bad thoughts would go away if I just stuck rigidly to my little mechanisms. Nothing worked, and my anxiety mushroomed. My coping skills were all false friends and, as a consequence, I was agoraphobic, prone to panic attacks, intrusive thoughts, hysteria and depression. By the time my husband walked out on me, I’d had years of this. I (honestly) couldn’t make it to the supermarket on my own, much less navigate my way through a break-up of this magnitude. I knew I had to get off the floor but I didn’t know what to do next. Everything was draped in fear.

Anxiety is a slippery, sneaky thing. It’s an illness that manifests itself in so many different ways that it’s often not diagnosed until the sufferer is absolutely desperate. You might spend years having panic attacks you don’t even recognise as panic attacks. You might assume that you’re seriously unwell, as though you’re having a stroke or a heart attack (like I did aged eighteen in a nightclub, much to the hilarity of my drunken friends), or research high blood pressure obsessively. You might be so ashamed of your intrusive thoughts that you never dare confide in anyone, let alone allow yourself to think you show signs of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Instead of dealing with the horrible images and ideas that pop into your mind, recognising that they’re just thoughts and can’t hurt you, you might spend years trying to neutralise and silence them. All of this can make you severely depressed, as if you don’t have enough to cope with. It made me cry hysterically, it made me stay in bed for hours. It made me sleep away days. It made me watch more daytime TV than a happy person should or would. It made me lose all hope far too young.

By the time they reach this stage, a person with an anxiety disorder will likely have come up with their own mechanisms to deal with such frightening thoughts and sensations. Those coping skills will be rigid and hard to challenge, never mind break down. Almost none of these will be helpful in the long term. More often they provide some instant relief, but ultimately serve to tighten the bonds of the worry they’re having. With me, these tactics included never returning to a place where I’d had a panic attack. Sensible plan, I thought, to avoid the same horrible situation happening again. Except I ended up putting an invisible cordon around most of London, including my local high street, the park and most shops. This later widened to include planes, lifts, motorways, anywhere too far away from a hospital, and the Underground (I was a lot of fun at parties). The immediate comfort this gave me was deceptive, since I quickly found myself trapped – unable to go anywhere that my mind had designated to be ‘unsafe’. Though it’s clear to me now that I’d been in the grip of anxiety for many years, I was so used to my own shoddy bargaining methods that I didn’t seek effective help with it until these tactics had a vice-like grip on me, and I was at a standstill.

If ever there is a trigger to make you try and change something, it’s the shock of your marriage collapsing before you’ve even made it to a year. Given that people who get divorced in the UK have usually managed about eleven and a half years before they pull the plug, tanking your vows as spectacularly as I did felt like quite the feat. Any longer and it might just have been seen as sad, unavoidable, or chalked up to ‘young people not sticking at anything anymore’, but eight months? It would be unwise not to question your life just a little bit after that.

And even without the added inconvenience of a marriage breakdown, I already knew that I had reached a crunch point. I’d avoided everything I found scary for so long that my world had shrunk to the point where I felt like I was suffocating. Despite all my careful management and precautions (read controlling everything and employing wildly irrational thinking – like I say, fun at parties), the worst had happened. The framework I’d been building for myself since I was a child hadn’t protected me from harm or humiliation. In fact, it had greatly contributed to it.

After my husband walked out, I’d spent several days weeping and drinking after my sister forcibly pulled me up from the foetal position I had adopted on the floor. Forgive me if I don’t give any detail here – I can’t remember a thing about those moments. I’m grateful to my brain for that, one of the only times it’s served me well. There must have been talking, sleeping and food but all I can remember is watching an entire season of Game of Thrones and my sister getting angry that I’d binge-watched it without her.

I took one day off work and then went back to the office, alternately crying in the toilets (my husband worked for the same company, that was fun) and sitting mute at my desk, listening to bagpipe music on my headphones in a strange attempt to find some mettle whenever I saw him walk by. As an aside, this was strangely effective and I would recommend it to anyone needing to feel strong. Start with ‘Highland Laddie’.

I felt stagnant, aware that I had to endure these painful and difficult emotions, but also worried that I might never feel truly better. Life continues around you, no matter how much your own world has been shattered. I could see normality heave into view and I didn’t want it. I was back at work, and I suspected that within a few months I might be over the break-up but still locked in my small space, anxiety and depression my only real bedfellows.

It’s easy to behave like nothing is wrong, even when you have a mental illness and feel like you’re going to be consumed by it. Even at my most miserable, I was good at holding down my job, cracking jokes, going out just enough so I wasn’t seen as a hermit. Many people become experts at this, even tricking themselves. I could probably have gone on like this forever, living half a life, pretending that I was OK with it. But something had broken, and I couldn’t do it anymore. I’d done it for so long, and it had become exhausting.

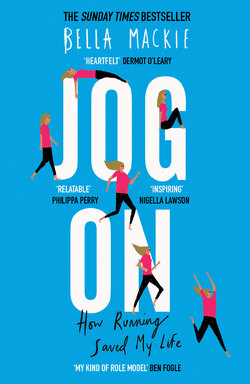

I saw myself exposed as a fraud – a cowardly kid play-acting as an adult, with no business being there. J. K. Rowling says that rock bottom became the foundation upon which she built her life – that because her worst fears had been realised, she had nowhere to go but up.[1] As it’s her, I can allow the cliché and even grudgingly admit that it fits. In Rowling’s case, she went on to create a magical world of wizards which helped her to become one of the richest women in the world. In mine, rock bottom spurred me on to go for a jog.

One week into my newly single life, I had the idea to run. There’s a moment in The Catcher in the Rye[2] when Holden Caulfield runs across the school playing fields and explains it away by saying: ‘I don’t even know what I was running for – I guess I just felt like it.’ Maybe I was just fed up with feeling so damn miserable, or perhaps I already knew that I had to try and do something differently, but that day I just felt like running.

I still don’t know why that was the tool I opted for in the midst of misery. I’d never done any kind of strenuous exercise before in my life. But I had spent a lifetime holding at bay the need to run away – from my mind, from my negative thoughts; from the worries that built up and calcified, layer upon layer, until they were too strong to chip away at. Maybe the sudden urge to run was a physical manifestation of this desire to escape my own brain. I guess I just wanted to do it for real.

Plus, I was impatient to bypass the ice-cream-binging stereotype of a break-up – I’ve always been keen for a quick fix. I wanted the bad feelings and heartache to be gone fast. A break-up is always a good time to try and do something new, after all. I had the added benefit of also wanting to break free of my lifelong fears, and I really felt like time was running out to do that. I was about to turn thirty, and I was terrified that I would use the break-up as another excuse to retreat, to box myself in even more, to be scared of life itself.

I was not ready to run across a playing field by any means. Being too scared to go to the supermarket put paid to any grandiose ideas like that. There was no climactic movie moment where I streaked across a prairie or raced through a downpour. In reality, I didn’t know what I was doing and I fleetingly wondered if I was in fact becoming delusional. It seemed like such a strange thing for me to want to do, and yet even as I argued with myself, I was gathering my keys and lacing up my trainers.

I put on some old leggings and a T-shirt and walked to a dark alleyway thirty seconds from my flat. It fitted two important criteria: just near enough to the safety of home, and just quiet enough that nobody would laugh at me. I felt absurd and slightly ashamed – as if I was doing something perverse that shouldn’t be seen. Luckily, the only sign of life was a cat who stared at me disdainfully as I mustered up the energy to move. I was grateful when the cat immediately vanished; and any hint of an approaching human would have made me stop instantly. This kind of private punishment was too raw to be seen by strangers.

With my headphones in, I searched for suitable music and settled upon a song called ‘She Fucking Hates Me’ by a band called Puddle of Mudd. Not to my usual taste, but the lyrics were suitably angry and I didn’t want anything that might make me cry (everything was making me cry). The song is three minutes and thirty-one seconds long and the line ‘she fucking hates me’ comes up as many times as you might imagine. I think I managed thirty seconds of jogging before I had to stop, calves screaming and lungs burning. But the song was kicking off my adrenaline and so I rested for a minute, and then started off again. I somehow managed to keep time with the shouting singer, mouthing the words as I screwed up my face and lumbered down the path. I managed an incredible three minutes in stages (nearly all the song!) before I gave up and went home. Did I feel better? No. Did I enjoy it? Also no, but I hadn’t cried for at least fifteen minutes and that was good enough for me.

To my own surprise, I didn’t leave it there. I wanted to, it had felt pretty grim, but something in me overrode all my internal excuses. I went back to that same alley the next day. And the day after that. Those first few attempts were all pathetic really. A few seconds, shuffle, stop. Wait. Go again. Freeze if a person emerged from the shadows. Feel ridiculous. Carry on anyway. Always in the dark, always in secret, as if I was somehow transgressing.

I didn’t know what I was doing, or what I wanted to get out of these alley runs. As a result, I got overly ambitious in the following weeks, and I encountered frequent and minor disasters. I got shin splints, which hurt like hell. I ran too fast and had to stop after wheezing uncontrollably. I tried to go up a hill and had to admit defeat and get on a bus when it became clear that the hill had bested me; I had a panic attack in a dark part of the local park when I mistimed sunset and realised that I was all alone. I fell over and cried like a child. Running felt like a language that I couldn’t speak – and not only because I was hugely unfit – it seemed to be something that only happy healthy bouncy people did, not neurotic smokers who were scared of everything.

Throughout my life, if I couldn’t do something well on the first attempt, I was prone to quit almost immediately. It was embarrassingly clear to me that I was not running well, or getting better at it. And yet, much to my own quiet disbelief, I carried on. I carried on trudging up and down the dark alleyway for two weeks. And when I finally felt bored rather than just merely terrified or out of breath, I went a little bit further. For the first couple of months, I stuck to the roads closest to my flat – my brain always looking for the escape route – looping around quiet streets, and cringing when cars passed by. I was slow, sad and angry. But two things were becoming clear to me. The first was that when I ran I didn’t feel quite so sad. My mind would quieten down – some part of my brain seemed to switch off, or at least cede control for a few minutes. I wouldn’t think about my marriage, or my part in its failure. I wouldn’t wonder if my husband was happy, or out on a great date, or just not thinking about me at all. The relief this gave me was immense.

The second thing, which was even more valuable, was that I noticed that I wasn’t feeling so anxious. Soon enough, I was reaching parts of the city that I hadn’t been able to visit in years, especially alone. I mean, I’m not talking the centre of Soho and its bustling crowds, but within a month I was able to run through the markets of Camden without feeling like I would faint or break down. I could not have done this if I’d been walking – I’d tried so many times but my anxiety would break through, palms sweating and looming panic taking over. But somehow, running was different. When your brain has denied you the chance to take the mundane excursions that most people do every day, being able to pass through stalls selling ‘nobody knows I’m a lesbian’ T-shirts suddenly feels like a red-letter day. By concentrating on the rhythm of my feet striking the pavement, I wasn’t obsessing over my breathing, or the crowds, or how far I was from home. I could be in an area my brain had previously designated as ‘unsafe’, and not feel like I was going to faint. It was miraculous to me.

Joyce Carol Oates once described how running enables her writing, positing that it helps as ‘the mind flies with the body’.[3] I take that to mean that your body takes your brain along for the ride. Your mind is no longer in the driving seat. You’re concentrating on the burn in your legs, the swing of your arms. You notice your heartbeat, the sweat dripping into your ears, the way your torso twists as you stride. Once you’re in a rhythm, you start to notice obstacles in your way, or people to avoid. You see details on buildings you’d never noticed before. You anticipate the weather ahead of you. Your brain has a role in all of this, but not the role it is used to. My mind, accustomed to frightening me with endless ‘what if’ thoughts, or happy to torment me with repeated flashbacks to my worst experiences, simply could not compete with the need to concentrate while moving fast. I’d tricked it, or exhausted it, or just given it something new to deal with.

Much research has been done on why running clears your head so effectively. Scientists seem intent on finding out why it works. I’m glad they are – I’d like to know exactly why running changed my life, but honestly I’m mainly just happy that it has. Studies have found that there is an increased activity in the brain’s frontal lobe after activity – the area linked to focus and concentration – in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and in elderly participants.[4] [5] Research on animals has shown that exercise produces new neurons – cells found in the hippocampus, associated with memory and learning.[6] It’s all fascinating stuff. But to my mind, none of this can adequately convey the rush that exercise promises to give you – that’s the main interest to most of us – the so-called runner’s high. (People with more experience with drugs than I have had will have to judge whether it is comparable to a more, er, recreational experience.) That an hour or so of energetic movement a day might fix our stressed and gloomy heads is understandably alluring, especially to those of us who’ve struggled with depression or anxiety for a sustained (read intolerable) period of time.

This is what I was beginning to dip my toes into. Weeks after my marriage collapsed, I was still sick with it all. At work, I would regularly go into the toilets and cry quietly. At home, I would put on my pyjamas the moment I got in and mindlessly watch whatever the TV had to offer. When I went out, I drank too much and would cry again (less quietly this time, to the delight of my friends). But when I ran, I left it all behind. Nobody could give me the dreaded sympathy head-tilt or an excruciating hug. Nobody even looked at me. I melted into the city, another tiresome runner in hi-vis. At home, I felt desperately lonely. I’d taken to sleeping like a starfish to head off the inevitable moment in the morning where I’d roll over and be met with a cold empty space, a reminder of all I’d lost. But when I headed out in the morning to run, I didn’t feel alone. I soon found that I was setting myself little challenges – go two minutes further today, run down that busy road that you’ve avoided for years tomorrow. The more I did it, the more I found that I was rediscovering the city that I lived in and yet barely understood – for so long a place fraught with imagined danger for me. I ran down Holloway Road looking at the tops of the faded old buildings that housed convenience stores and supermarkets. I discovered railway lines that ran like arteries through built-up estates, hidden from plain sight. I ran along the canal and found an expanse of brambles, wild flowers and baby ducklings swimming along next to me. The panic attacks were fading away. Not once did I feel the need to find the exit; my feet were in control and I was running purposefully, not running away. I was taking things in for the first time without my mind screaming warnings at me.

It would be taking things too far to say that I felt childlike when I ran, but it definitely gave me a sense of lightness and abandon that I only really see in young people (and drunk people, but they then have a sense of regret which I hope children don’t experience). This shouldn’t be a surprise; from an early age we are encouraged to skip, hop, dance, run and play team sports. As Louisa May Alcott wrote: ‘Active exercise was my delight from the time when a child of six I drove my hoop around the Common without stopping, to the days when I did my twenty miles in five hours and went to a party in the evening. I always thought I must have been a deer or a horse in some former state, because it was such a joy to run.’[7] We instinctively know that the young need to use their bodies, and not only for their physical health. Studies on this in the UK are somewhat limited, and usually cross-sectional, but a NICE study on children and exercise remarked on the results of one survey which reported a higher risk of depressive symptoms among 933 eight- to twelve-year-olds classified as inactive, and among children not meeting the standards for health-related fitness compared with those who were considered active.[8] Analysis of clinical trials looking at exercise and its effect on depressive symptoms in teens aged thirteen to seventeen seemed to show that physical exercise is an effective treatment strategy.[9]

I never gave myself the chance to learn this when I was younger. It would be simplistic to say that this was all because of anxiety, although it was certainly a contributing factor. I was chubby, rather unpopular and viewed sport as a hideous popularity contest. I hope that things have changed since I was at primary school, but sports were also determined by gender. You almost never saw girls on the football pitch, and it was perfectly acceptable for us to gather in sedentary groups around the playground as the boys burnt off their energy kicking a ball about. The divide is still marked – a 2013 study found that half of British seven-year-olds don’t get enough exercise, and the gap between boys and girls was one of the most worrying revelations.[10] Professor Carol Dezateux, one of the lead authors on the study, said of the findings: ‘There is a big yawning gap between girls and boys. We need to really think about how we are reaching out to girls … The school playground is an important starting point. Often you will find it dominated by boys playing football.’

The rate of exercise drops by as much as 40 per cent as children move through primary school.[11] And this decline didn’t stop for me at secondary school, where we were marched down to a sodden field to play hockey (I told you it was gendered, netball was the only other option). I would inevitably be picked last and then proceed to stand as far away from the action as possible. As we got a bit older, our options for exercise were an unaccompanied walk round the local park, or aerobics. Given that the park contained a) boys and b) cigarettes, guess where I went?

Women in Sport recently conducted research into the variation between girls’ and boys’ levels of exercise, and they found that just 12 per cent of girls aged fourteen got enough physical activity every week.[12][13] Despite this dismal number, 76 per cent of fifteen-year-old girls said that they would like to do more physical activity but were discouraged by the sports on offer to them. The other (and to my mind, sadder) reason that they gave for not participating was that they thought that sport was ‘unfeminine’. I remember that feeling clearly – a sense that exercise was just not dignified or elegant. It involved sweat and grunting and angry screwed-up faces, and could well end up in embarrassment, a thing all teenagers wisely (or perhaps just instinctively?) avoid like the plague.

As children leave full-time education, exercise rates can decline further. Sure, some will make time for a run or a gym session, but it gets harder. If you end up going to university, it’s unlikely you’ll be making time for sport when there’s so much work to do and terrible fancy dress parties to attend. There’s a reason why people gloomily talk about the ‘Freshers’ Fifteen’ – the old but accurate cliché that you put on weight in the first year of studying. This mirrored my experience, where activity meant getting out of bed past midday and possibly walking to the local shop for fags and crisps. A fairly normal experience for a student then, except that, unfortunately, this is also the age when some anxiety disorders are known to manifest themselves most severely – for example, OCD usually develops before the age of twenty.[14] While aspects of anxiety will be present in kids from a much younger age (phobias show up in children as young as seven), early adulthood is the perfect time for more serious aspects of anxiety and depression to hit, and hit hard. And that shouldn’t be surprising to anyone – after all, this is the time when the carefully regimented structures of education and family fall away and you are mostly in charge for the first time. Some thrive with the new responsibilities that they’ve been given, but many will not. I did not.

Having managed to leave school with most of my childish worries lying fairly dormant, I was knocked off my feet one day at university, when, completely out of the blue, I had a terrible panic attack in a courtyard. I was so unprepared for these feelings to rear up on me again that I deployed my trusty ostrich manoeuvre and tried to ignore it. Instead of questioning why it had happened, I simply avoided all thought of it. But the feelings of rising panic increased in a frighteningly short period of time, and within a fortnight I had developed a new symptom which horrified me more than any I had previously experienced: disassociation. The clever (not a compliment) thing about anxiety is that the moment you’ve got a handle on one thing (night sweats, panic attacks, dizziness, nausea, headaches – come sit by me), it’ll throw you another one, and you better believe it’ll be worse.

Disassociation (or derealisation) is a condition which makes the world suddenly seem unreal. Actually, I don’t think I’ve made this sound as heart-stoppingly awful as it is. It’s not just the world that feels unreal – it’s that the people you love the most seem fake, your home feels like a film set, your dog looks flat, your own face doesn’t look like your face. Everything feels staged and wrong and just … off. I later learnt that psychiatrists believe that it’s a sensation your brain employs when it’s exhausted from worrying – shutting your mind down (somewhat). So it’s actually an attempt at protection, but to me it feels a bit like a mate who sleeps with your partner and earnestly explains that they only did it to help you. I’m not saying thank you either way.

What would have happened if I’d just put on some trainers and tried to outrun these awful feelings? It’s something I’ve asked myself repeatedly in the years since. Nothing is as simple as that, and it would be insulting and irresponsible to even hint that it could be. Running is not a cure-all for severe mental illness, or anything else for that matter. It’s right to acknowledge that early on. But I often think of the girl I was in my twenties and wish I could go back and try other things, as many of my friends did when things got difficult. Your twenties are a time for experimenting, having fun and enjoying everything that life may offer you, or so we’re told. Instead, for many people, I think they are a time of massive insecurity, debt, and a sense of displacement – a decade of worry and fear. So I did what I could. I dropped out of Uni, went to a psychiatrist and took the antidepressants that I was swiftly prescribed. What else could I do? At this point, suicidal thoughts were creeping in, and even through my wildly unreal prism, I could tell that those thoughts would only lead somewhere I didn’t want to think about in further detail.

Despite all of this, I was extremely fortunate – it’s so important that I recognise that. I had a family who, while not fully understanding at all why their daughter was crying hysterically all the time and refusing to go out, had the resources to pay for me to see a professional. Seventy-eight per cent of students reported a mental-health issue in 2015, and 33 per cent of those had suicidal thoughts.[15] My NHS GP was kind, but could only offer to put me on the waiting list for therapy, which stood at six months back then. More than one in ten people currently wait over a year for any kind of talking therapy, with the same number having to scrape together the private funds to pay for help themselves. Some universities are now offering exercise classes (in tandem with the usual talking therapies) to students with depression and anxiety, an encouraging sign that experts in mental health are still linking up the physical and the mental in ways we’ve not yet fully explored.

It’s not just depression and anxiety that an activity like running has been proven to help with. Even as you read this, you might well be experiencing something equally as isolating: you might be feeling lonely. Loneliness is something that we increasingly recognise has a huge impact on our mental and physical health, yet so many people still feel unable to admit to it. The stigma that surrounds it can make us feel pathetic, unlikeable, inadequate, and it can be really hard to see a way out of it. People often say it’s hard to walk alone in life. Sometimes it’s bloody hard to run alone too. This may be why Parkrun has become such a hit across the UK. Every week, at 414 parks scattered around the country (and in fourteen countries worldwide), people congregate early in the morning to jog together.[16] Though I often need to run alone, some of the best routes I have taken have been with my sister, with an ex-boyfriend and with new friends, where we’ve shuffled along, gradually getting to know one another better while pushing each other forwards. When you’re unable to put on a front because you’re wheezing and sweating profusely, it’s genuinely astonishing how close you can feel to the person next to you doing the same.

As I was writing this book, a survey of more than 8,000 people was carried out by Glasgow Caledonian University to look at whether running can make you happier. The questionnaire used the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire, and asked people to answer questions using a rating between 1 (unhappy) and 6 (extremely happy). Parkrun participants emerged with an average of 4.4, compared to the general population, who scored an average 4.[17] The sense of community that running with others provides ranked highly with the responders, who said that the support and sociable elements of running with others was invaluable.

Sara, who suffered with postnatal depression after the birth of her first child, told me that running with a friend provided some light in the dark. Someone who would pick her up and force her out, someone who pushed her on and kept her going when she might not have bothered herself.

‘I’m quite a solo runner, and a bit of a hermit, so I actually like running by myself and get a lot of benefit from that, but at the same time I know the fact that I had one friend who kept pushing me (in a nice way) to run was probably a key part of my recovery that one time,’ she told me. ‘I might’ve done it myself eventually, but she certainly speeded things along. And, of course, having meaningful connections with other people is a big part of sustaining good mental health. I’ve always felt that it’s the physical act which is key for me, because I get kind of addicted to the physical sensations, but actually I realise now that without that key friend I might not have managed to get that far!’

So many people I spoke to during the course of writing this book spoke of the important social aspect that running provides. Running with a partner, or a friend, or just meeting people out and about can be a balm to the isolation that mental-health problems create. Even if you run alone, you’re connecting with the world around you, and it’s still surprising just how effective that can be when you’ve not spoken to another person in days.

Alongside the effect exercise can have on depression and anxiety, there have been some amazing clinical trials that have looked into whether aerobic exercise can help people who suffer from schizophrenia. A 2016 study at the University of Manchester reported that working out reduced the symptoms in patients with psychosis by 27 per cent.[18] Initial trials in the USA on veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have also found that exercise brings about a reduction in fear, along with a lessening of the physical symptoms. Of course, all these results do not negate the need for therapy, medication and other support structures, but they bring hope that there is perhaps also more that we can do to help ourselves.

The pills that I took definitely helped, and I was able to look at myself in a mirror again without wondering who the fuck was looking back at me. I got a job, was able to go out again (while always looking for the fire escapes), and managed a few relationships. I was patched up, in the most basic sense. Nothing was fixed, but I wasn’t staring at walls and hyperventilating either, so I took the pill. I say all this, not to give you a small insight into my not particularly special mind, but to show how easy it is to accept the most pallid imitations of existence when you’ve got a mental illness. To paint on a small canvas, and to pretend that you’re happy with the narrow perimeters you’re able to move within. Not at all a life wasted by any means, but a life limited in a variety of ways. It can feel just about fine, but it can also feel stunted, a compromise that takes a lot from you. So to find something that breaks you free of this can feel utterly miraculous. For some that may mean medication, for others meditation. My mother does yoga whenever she feels low. A colleague of mine lifts weights to keep depression at bay, and one friend boxes because he feels far too angry and it helps keep those thoughts under control. One girl I know with severe bipolar credits her treks across the local park with saving her in small ways every day. I even know somebody who cross-stitches when she feels that familiar anxiety rushing in. Somehow, after a decade of settling for merely ‘managing’, I’d found the thing that broke me out of it: I’d found running.

One day, after a few months of gingerly testing myself trudging around the local streets that I’d come to know with my feet, I decided to go further. I ran to my firmly set boundaries, and then I ran past them. I ran into the heart of the city, towards one of the bridges that traverse the Thames and beckon you over with the promise of light and air, and I headed across without a backwards glance. I crossed another bridge, intoxicated by the sunshine on my skin, and I ran into Parliament Square, thronging with the usual tourists and vendors and honking cars. I passed through Soho, marvelling at the noise and the rickshaws and the sex shops. I kept going, like a neurotic Forrest Gump, until I physically couldn’t go any further. And when I stopped, I wandered around. The pit in my stomach wasn’t raw, I wasn’t checking my breathing – I didn’t notice my body at all. I was able to take in my surroundings and enjoy them. I felt triumphant. I felt … happy.

When you do something that allows you a respite from misery, it can be hard not to get addicted to it. We all know that just as a person who uses drugs and alcohol can quickly become dependent on them, and in a different way, the same can be said of exercise. The rush I experienced that made me feel so happy that day in central London can be hard to say goodbye to, even briefly. Once you’ve found something that makes you feel halfway to normal, why would you not step it up? After all, exercise is healthy – we’re constantly being told to do more of it by our doctors, the media and now increasingly by Instagram stars and vloggers who preach about clean eating and physical exertion. But for someone who is looking for a crutch, or a way to feel less lost, exercise can move quite quickly from enabling you to dominating you. Although there are comparatively few studies on exercise addiction, one from 2012 found that 3 per cent of gym-goers fit the description of an addict, and another study suggested that number might be more like 25 per cent for amateur runners.[19] It can be extremely hard to notice when something that you feel is doing you good begins to take over your life.

Every person will have their own measure for how much is too much, but my criteria would include the following: Would you say no to a night out because you don’t want a hangover before a big workout? What about never having lunch with colleagues because you use that time to run? Or might you get panicky when there’s a weekend wedding coming up because you worry that you’ll miss a gym session? I would have to reluctantly say yes to two of these questions (I will absolutely run through a hangover, come on), because at times, running has unquestionably become an obsession for me. The utter joy I found in the absence of panic attacks, irrational thoughts and all the other symptoms that anxiety brings with it (there are over a hundred, just try to beat me) was intoxicating. Feel that heady haze often enough and it becomes easy to turn down other things. Online, you’ll quickly find countless stories of people who have made very real sacrifices in their lives to maintain their exercise routine – people doing workouts three times a day, those who would panic if they missed a cycle or a swim but became exhausted from the commitment. And this goes against what the person hoped it would do in the beginning. Running was something that allowed me to have a life – a real life, with friends and new experiences and even risk. It was a wonderful means to an end, but it was never meant to be my whole life.

After a life lived in varying degrees of fear, once you feel as though you’ve managed to find an even keel, you guard it fiercely. Any normal sign of panic or a fleeting feeling of doom can knock you off your perch – making you worried that you’re going to be sent straight back to square one, do not pass go. In those moments, I would step up my routine – putting on my trainers twice a day, pushing myself harder. At times like this I hated running. I felt like a hamster willingly signing up to a new wheel, but now unable to get off. I might have continued in this vein, were it not for something catastrophic that happened less than a year after my husband had pushed off. The woman that I loved as a second mother, the woman who gave me my first job, and taught me how to be an adult, and hugged me and laughed at me and screeched at my gossip: she died. She died far too young, and she took with her a joy that I haven’t seen in anyone since. In the days and weeks afterwards, as those left behind began to understand just what had been taken from us, we were enveloped in sorrow. I ran, hoping to ameliorate the grief, hoping that my fail-safe would do what it had been doing for the past nine months. And it helped, it truly did. You find it hard to cry when you run – for one thing, I think you’d end up feeling like you were in a music video from the nineties, weeping as you dashed through a downpour wearing something bedazzling – and running forces you to understand, in the most literal sense, that the world keeps moving even when you think it shouldn’t, even when you’re furious that it does. I’m not the first to use running to try and get over a great loss – the world’s oldest marathon runner, Fauja Singh (a sprightly 107), started running in his late eighties to get over the loss of his wife and children.

But while running provided a balm, an event of such horrible magnitude also showed me that it had its limitations. And that was something I needed to learn. I’m loath to say that the loss of a much loved friend can bring about anything positive. It just can’t. But I did come to understand that you should not fear real sadness, nor try to shy away from it. And that doesn’t mean that you’ll fall down the rabbit hole of mental illness again, nor that you’ll never recover. You can’t fully insulate yourself against true sorrow, but you can learn to recognise the difference between a natural and worthy emotion like grief, and an irrational and unhealthy one, like panic. I scaled back my escalating running schedule and allowed myself to feel sad sometimes. By doing that, I remembered why I had come to love doing it so much.

Running is not magic beans and I now know that I can’t expect it to inure me to the genuine sadness of life. But throughout tough periods in my life, and without realising it, I had finally acquired a coping skill, one that has helped me every day since I found myself on that floor, wondering how I’d ever get up. It’s something that has taken me out of my self-made cage, propelled me towards new jobs, new experiences, real love and a sense of optimism and confidence that I can be more than just a woman with crippling anxiety. It has given me a new identity, one which no longer sees danger and fear first. It’s not an exaggeration to say that I ran myself out of misery. It has transformed my life.