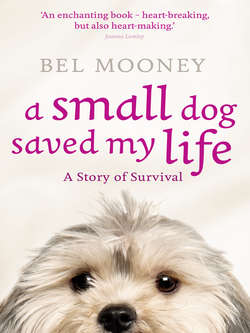

Читать книгу A Small Dog Saved My Life - Bel Mooney - Страница 6

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеWhat counts is not necessarily the size of the dog in

the fight; it’s the size of the fight in the dog.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, Address,

Republican National Committee,

USA, 31 January 1958

When I look in the mirror I see quite a small person: not tall and quite slight. My skin bruises easily and as I grow older I notice more and more weaknesses, from wrinkles to stiff limbs to hair that is no longer thick and beautiful, as it once was. This is, of course, all inevitable. I can do no more about it than I can change all the experiences, good and ill, which have shaped the mind and spirit within this vulnerable, mortal frame. In this respect I am exactly like you, the über-reader I always imagine as a friend when writing. We can (men and women alike) anoint ourselves with unguents in an attempt to keep time at bay but the most useful exercise for the soul is to square up to your life, no matter how much it terrifies you, and try to make sense of it. That is the true business of self-preservation and it is what I try to do in this book – in the hope that this small, individual journey, one woman’s personal experience of love, loss and survival, may (quite simply) be useful. Most of us have endured, or will endure, pain in our lives. If this book has any message it is that recovery and salvation can come from the most unexpected sources, and that largeness of spirit will most equip you for your personal fight.

Working in my study one summer day, writing the journalism which pays the bills but wondering if I would ever return to fiction and slightly desperate for something – anything – to break that block, I flexed a bare left foot which touched my Maltese dog, Bonnie. She sleeps on a small blue bed, patterned with roses, which sits beneath my home-made work surface. All day she waits for attention, rising to follow me wherever I go in the house, longing for the moment when, feeling guilty, I at last suggest a short walk. At which point she leaps up, races up the stairs from the basement and scrabbles wildly at the front door, like a prisoner incarcerated in the Bastille who hears the liberators outside and screams, ‘I’m here! Save me!’

On that day in 2008 I suddenly realized how great a part my dog had played in my own salvation, and that I wanted to write about that process. I was encouraged by the experience of an artist I admire very much, David Hockney, whose paintings and drawings of his two dachshunds, Boodgie and Stanley, show the pets curled on cushions, lapping water, rolling on their backs. You don’t have to be a lover of small dogs to be delighted by these works, and yet they should not be underestimated, despite their simplicity. What looks like a set of speedily executed images of two faintly absurd, brown sausage dogs adds up to an idiosyncratic statement about love.

In the introduction to Dog Days (the 1998 book which collects this work) Hockney writes, ‘I make no apologies for the apparent subject matter. These two dear little creatures are my friends. They are intelligent, loving, comical and often bored. They watch me work; I notice the warm shapes they make together, their sadness and their delights.’

What does he mean by ‘apparent subject matter’? He’s painting his funny tubular dogs, isn’t he? End of story. Yet not so. In an online interview the artist explained, ‘I think the real reason I did them was as a way of dealing with the recent deaths of a number of my friends … I was feeling very down. And I started painting the dogs and realized this was a marvellous subject for me at this time, because they were little innocent creatures like us, and they didn’t know about much. It was just a marvellous, loving subject.’ Asked (mad question!) if the dogs had any sense they were the subject of Hockney portraits, the artist replied, ‘The dogs think nothing of them really. They’d just as soon pee on them. They don’t care about art since they’re simply on to higher things – the source of art, which is love. That’s what the paintings are about – love, really.’

So, on an unconscious quest to deal with loss and celebrate love, one of the most popular artists of our time stayed at home and ‘saw the nearest things to me, which was two little dogs on cushions’. Similarly, on my own quest to understand how love can survive even an ending, how a marriage can go on reverberating even after divorce and how the process of reinvention in a human life reflects the very movement of the universe and must be embraced, I stayed at home and stroked the nearest thing to me, which was a tiny white dog with a feathery tail who needs me as much as I need her. I had so much to learn from the force of devotion within that minuscule frame.

Dogs are patient with us; they have little choice. They continue with their dogged work of saving our lives, even if we don’t know it’s happening. Long before my foot reached out to rub her soft white fur that day, my lapdog was asking me to regard her as Muse. She was demanding proper attention, as well as instinctive affection. She was saying, ‘I’m here!’ And it worked. Since then my ‘animal companion’ (as the modern phrase insists, implying equality rather than ownership) has inspired my ‘Bonnie’ series of six books for children, which stars a small white dog from a rescue home who, as the saga progresses, helps to cheer and restore one unsure, unhappy boy and his family.

Now she is the beginning, middle and end of this book’s story too – and, like Hockney, ‘I make no apologies for the apparent subject matter.’ I am writing about what happened to me between 2002 and 2009, using my dog as a way into a painful story, and a way out of it too. During that time my marriage ended and life was turned on its head. What do dogs know about marriage? Probably a lot – because they are in tune to our feelings and it’s hard to hide things from your dog. As I get older I want to share more, hide less. That’s why I’m willing to invite others to come along on a walk with my pet, in the hope that the activity might act as ‘therapy’ for them, as it has for me. Dogs are good at therapy – so mine will help me tell this story of a love (affair). Or, rather, a tale of many loves.

It’s not easy to embark on anything resembling autobiography, although bookshops are flooded with usually ghosted ‘celebrity’ tomes and there seems to exist an avid readership for the recollections of (say) a footballer or his wife who are not yet 30. Too often that sort of thing is little more than an extension of newspaper or magazine gossip. What is written will be inevitably full of half-truths and blurred ‘fact’ as the celebrity dictates the view he or she wishes to present. Even the finest biography will be hampered by unknowing.

If the biographer feels impelled to smooth over instead of flay (and much flaying goes on these days, both in books and column inches, which I doubt adds to the greater good), how much more will the writer of a personal memoir feel the need to evade? As I was working on this book I was entertained (as well as appalled) to read a prominent newspaper diary item about my work in progress which shrieked ‘Revelation!’ – although not in so few words. The journalist predicted that I would be blowing the lid off relationships within my ex-husband’s family, and so on. Now I ask you, why would I want to do that? I agree with the nineteenth-century historian Thomas Carlyle that in writing biography sympathy must be the motivating force. I have no aptitude for slashing and burning, and am glad to say that I shall go happily to my grave never having learnt the arts of war.

A partial life is a slice of reality – a taste which leaves us wanting more. The multifaceted art of memoir suggests that even a few months within a life, when something extraordinary happened, can offer a story of almost mythic power. In the ‘new’ life writing (a fascinating topic now, especially in the United States) the freedoms of fiction have been introduced into autobiography and obliqueness is allowed. The writer can say, in effect: ‘This is what happened that summer, and afterwards. It’s not the whole story by any means, because much must remain private. Still, I offer this as an act of mediation. If it happened to you, this might help you survive. This might well stand between you and your nightmare.’ That is what I am trying to do in this book – although not without knowledge of the pitfalls.

At the end of 2003 I encountered a successful woman writer who had read in the newspapers about the end of my 35-year-long marriage. ‘I hope you’re going to write a book about it!’ she said with glee. I shook my head. ‘But you must!’ she went on. ‘Tell it like it was! And if you don’t want to write it as a true story, just turn it into a novel. People will know it’s the truth. You’ll do really well.’ When I protested that I hated the idea, she asked, ‘But why shouldn’t you?’

Maybe her counsel made commercial sense, but her avidity drove me further towards reticence. There is enough personal misery swilling around the shelves of bookshops without me adding to the woe, I thought. After all, any celebrity autobiography nowadays is required to take us on a turbulent ride from trouble to trouble – dodgy parents, colon cancer, mental illness, alcohol and drug abuse and the rest. The non-celebrity stories deal in poverty, ill-treatment, sickness and perversion to a degree that would astound even Dickens, who knew about the seamier sides of life. A publishing bandwagon rolls along fuelled by pain and suffering, with the word ‘misery’ going together with ‘memoir’ – like ‘love and marriage’ or ‘horse and carriage’. Happy lives, it seems, don’t make good ‘stories’. But some of the stuff published is not so much gut wrenching as stomach churning.

So this is not a misery memoir. No, this is a happiness memoir, although it deals with unhappiness and recovery. It is just one portion of the narrative of a few years in my life and in the life of one other significant person – the man I married in 1968. Other people close to us have been left out; I do not intend to embarrass either his second wife or my second husband, or indeed to reveal what members of our respective families said, thought or did. Still, since I told that person that I had no intention of writing about the dramatic break-up of my first marriage, things have changed – although my rejection of the notion of ‘telling it like it was’ is the same. For there is always more than one Truth. Because the experience and its aftermath would not go away, I found myself keeping a ‘quarry’ notebook for the novel which will remain unwritten, as well as my essential diaries and notebooks, and realized that my own process of learning from them would go on. In the end the impulse to write became like a geyser inside. The aim must always be to find meaning in what happened, for what else can a writer do? I have to agree with the screenwriter Nora Ephron who was taught by her writer parents unapologetically to view her own life as a resource.

So, yes, a memoir of happiness of sorts, because the good times and the bad are indivisible in my memory and roll on forever in the mind’s eye like a magic lantern show, or (to be more up-to-date) what Joan Didion calls ‘a digital editing system on which … I … show you simultaneously all the frames of memory that come to me now … the marginally different expressions, the variant readings of the same lines’. Writing about the deaths (within days) of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, and her daughter, Quintana, Didion explains (in The Year of Magical Thinking) that the book is her attempt to make sense of the period that followed the deaths, which forced her to reconsider so many of her ideas about life, luck, marriage and grief.

Like Joan Didion I was forced to confront not physical death but a different sort of bereavement: the end of a way of life I had thought (somewhat smugly) would continue into a cosy old age. The shattering of that conviction made me confront a myriad of other certainties and set me upon a strange path through the woods – which led, after a while, to the decision to write this book.

‘No,’ I said to people during that process, ‘I’m not writing an autobiography – I’m writing a book about dogs.’ The oddness of that statement was enough to stop questions. It came to me one day that all the qualities we associate with dogs, from fidelity to a sense of fun, are ones I admire most in human beings. I also know that small dogs display those qualities in a concentrated form – pure devotion distilled to fill the miniature vessel. Of course, anthropomorphism is dangerous. It pleases us to attribute virtues to canine creatures, who have no moral sense, and when the decision was taken to erect a magnificent monument in central London to all animals killed in war, I remember thinking it feeble-minded to use words like ‘loyalty’ and ‘heroism’ and ‘courage’ about creatures who had no knowledge of such abstracts.

There’s a famous Second World War story about an American war dog called Chips who was led ashore by his master, Private John R. Rowell, when his outfit landed at a spot known as Blue Beach, on Sicily’s southern coast. They were advancing on the enemy lines in darkness, when they came under machine-gun fire from a pillbox which had been disguised as a peasant’s hut. The troops flung themselves to the ground, but the dog charged the machine-gun nest, despite the stream of bullets. Private Rowell said, ‘There was an awful lot of noise and the firing stopped. Then I saw one Italian soldier come out of the door with Chips at his throat. I called him off before he could kill the man. Three others followed, holding their hands above their heads.’

I doubt Chips was a titchy Maltese, a Yorkshire terrier or a papillon, although a feisty little Jack Russell might have done some damage, despite his size. Still, the issue is: can you call a dog ‘brave’? Was a contemporary writer accurate to assert that ‘this American war dog single-handed and at great risk to his own life eliminated an enemy machinegun position and saved the lives of many of his comrades’? Even the most passionate dog lover must admit that the soldier who acts does so in full knowledge of the consequences, carrying within his heart and mind images of parents, wife or girlfriend, children – and risking life despite all. But the dog does not. Men and women act from courage; animals merely act.

Is that true? I do not know – and nowadays I don’t really care. In her profound work Animals and Why They Matter the philosopher Mary Midgely points out that ‘a flood of new and fascinating information about animals’ in recent years has educated people who mentally place animal welfare ‘at the end of the queue’. She states her belief in ‘the vast range of sentient life, of the richness and variety found in even the simplest creatures’, and believes it irrelevant that a dog’s experience is very different from our own. Philosophers and writers alike have long suggested the idea of the dog as (yes) a moral teacher. This is not fanciful. Anyone who has (for example) studied the psychology of serial killers will recognize the ‘flies to wanton boys’ argument behind Kant’s words: ‘He who is cruel to animals becomes hard also in his dealings with men … The more we come into contact with animals, and observe their behaviour, the more we love them, for we see how great is their care of their young.’

Once I was an ignorant young woman who professed dislike of these animals. Now in my sixties, the more I read about dogs and learn what an influence they have had on their owners and the more I love my own small example of the genus, the more I understand Franz Kafka’s statement: ‘All knowledge, the totality of all questions and answers, is contained within the dog.’

This story asks questions and offers some answers about change and how we can deal with it, in order to survive. It is also about dogs in history, art and literature, dogs as therapy, dogs as everything they can be to humans, helping us in the process of living. The narrative is aided by those diaries and notebooks which were such a catharsis and by a few extracts from my published journalism. I choose to tell this slice of a life discursively, because I have never trodden a straight path and love the side turning which leads to a hidden shrine. During a long career which began in 1970 I have worn many hats – reporter, profile writer, columnist, children’s author, commentator on women’s issues, travel writer, critic, radio and television presenter, novelist – but it is my latest incarnation which provided the final driving impetus to write this book. In 2005, rebuilding my life, I became – quite by accident, as I will explain – an advice columnist on first one, then another national newspaper. The truth is that, although I have loved all aspects of my working life, I find this the most significantly useful role I have ever played, apart from those of wife, mother, daughter and friend.

But the work causes me much sorrow too. So many letters, so much heartbreak, all transferred and carried within me, with none of the safeguards in place for the qualified psychotherapist. This has opened my eyes, in a way impossible before, to the pain caused by the end of love and the destruction of marriage, although the two do not necessarily go together. Oh, I know about the other forms of loss as well. When widows or widowers write to me from their depths of grief and loneliness, it is very hard to know what to say. Death has to be faced, but no such glib statement of the truth of existence is any use to those in mourning. Still, I do my best. I have never been afraid of writing about bereavement. It’s easier than addressing vindictiveness, selfishness and despair.

How do you advise people who are dealing with the end of love, or (especially) the ‘death’ of a long marriage? What resources can be drawn on to cope with the loss of all you were and all you think you might have gone on to be, with that person at your side? How do we make ourselves whole again? The entirely unexpected end of my long marriage confronted me with those questions, and I bring some of the knowledge gained to my job and to this book. Some people will think that all should remain private but I have never been able to shut myself away, and remain unconvinced that battening down the hatches is useful. For one thing, the act of remembering halts the rush of time, as well as being profoundly healing. Seamus Heaney expresses this idea in Changes: ‘Remember this. It will be good for you to retrace this path when you have grown away and stand at last at the very centre of the empty city.’

Second, I know it is helpful to share stories. My work as an advice columnist has proved to me without doubt that there is valuable consolation for others in telling how it was for you. To hell with privacy, I say – though not with reticence. We need each other’s stories, all of us, just as I need my small dog. We have to be courageous, just as my dog is brave, no matter how small. We can learn from each other and go on learning, as I have learnt from her. The poet and naturalist David Whyte perfectly encapsulates the motivation behind this evocation of life and dogs:

To be human

Is to become visible

While carrying

What is hidden

As a gift to others.