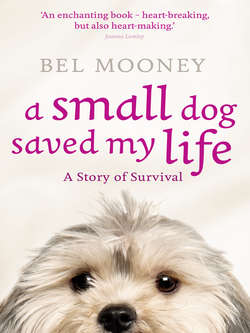

Читать книгу A Small Dog Saved My Life - Bel Mooney - Страница 7

One FINDING

ОглавлениеThere is much to learn from these dogs.

And we must learn these things over and over.

Amy Hempel

I never knew where she came from and will never know. The central mystery will always be there when I look at her, reminding me that my mirror offers a similar puzzle: who are you? It is a Zen question, the one Gauguin must have been thinking when he painted Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, every vibrant brushstroke telling us that the answer can never be known and the central mystery has to be accepted in your journey towards the end. All this I knew. But the coming of my little dog was to herald a deeper awareness: that we cannot know what will happen to us. Not ever.

Yet I have always needed to control things. Spontaneity makes me uneasy. I like to know the history of a house, the provenance of a picture, the origin of a quotation, because such knowledge is a hedge against chaos. I plot and plan. My books are arranged alphabetically or (depending on the subject) chronologically, and my shoes and gloves have to be ordered according to the spectrum. Years ago, having children presented me with a philosophical shock to match the physical and emotional pain, because those outcomes I could not control. A stillborn son and a very sick daughter served only to increase my need for form and structure. Retreating within the four walls of the life I planned was the only security. This was Home. Everything therein could be organized, a perfect bastion created to face down the imperfections in the world outside.

Then, quite unexpectedly, there came from nowhere the smallest dog. She pitter-pattered into my life before I could think but, had I stopped to consider, she certainly would not have been let in. These are the moments when the universe smiles and plays a trick. You get up one morning with no inkling that the day will bring a life-changing moment. The face of a future lover seen across a room, a sudden stumble which leaves you with a black eye, a phone call which will seem to leave your career in tatters, at least for a while. There can be no knowing what will pop out from under the lid of the scary jack-in-a-box – so be ready for it all (I advise people), because then you won’t be surprised. But Bonnie surprised me. She slipped in under the radar. My permanent high-alert system must have short-circuited, leaving me wide open. The small dog arrived with the unstoppable force of a Sherman tank, changing things for ever.

You should always share things with the people you love, and make decisions together, but I decided on this tiny creature on impulse. I told no one – not even the most beloved of my heart – that a ‘toy’ dog, an animal fit only for laps and satin cushions, would come to live on our farm. What did I think when I first saw her – apart from the obvious, ‘Ahh, how can a dog be so small?’ As I said, I did not think at all. But looking back, with fanciful hindsight, surely I knew she was destined to share my life. Hers was the face of the lover seen across a room – the new person, the One. How could I have known that this dog spoke to an urgent need I had not identified, whilst her mixture of vulnerability and toughness would prove an exact match for my own? Bonnie the abandoned creature was to become my saviour during my own time of abandonment; she who was so small taught me most of what I was to learn about largeness of spirit. The lessons carried within the soul of my little dog go on and on. But that is to jump ahead …

This is how it happened.

On 13 June 2002 I drove to Bath’s Royal United Hospital for a meeting of the art committee. Our task was to cheer the corridors of the hospital with artworks, and to commission an original work of sculpture with funds from the National Lottery to ‘animate the aerial space’. I liked that phrase; it would be a sort of hanging, flying creation in the atrium. It might distract patients afraid of this part of their life journey, reinvigorate families who face so much waiting and generally cheer up everyone who passed that way, from the consultant to the cleaner. My own life is enriched by art every day; naturally I agree that hospitals should be too. So I said I would join the committee, and give time and enthusiasm to the ‘unnecessary’ decoration of a necessary place.

But I dislike meetings; my claustrophobia kicks in within minutes and I want to leave, do a runner, get the hell out of the ‘good works’ and go home to a glass of wine and Al Green blasting loudly in the kitchen. I feel a fraud: a ‘public’ figure who is really somebody disreputable, who wants to hang out and do nothing. Yet the desire to flee fights with my need to give something back – for if you lead a life full of blessings you need to keep them topped up. This is karma: the meals on wheels of a good life. That day it was taking me nearer to my soulmate dog.

The committee met in the hospital’s charity office and we were all sitting around waiting to start when the door opened and Lisa (one of the younger committee members) came in, holding something in her hand. Because of the table, I couldn’t see properly; she came further into the room and I realized it was a dog lead. With something on the end of it. I craned my head and glimpsed a flurry of white. It was the smallest dog I had ever seen.

Lisa was the head of fundraising for the RSPCA’s Bath Cats and Dogs Home. Strangely, J and I had been there for the first time ever, just two days earlier. We went to recover his beautiful Labrador Billie, my fiftieth birthday present to the husband who had everything else and therefore needed a dog. Here I must explain that I was never a dog lover – not as a child when my grandmother got a snappy corgi called Whiskey, nor at any other time in my life. Yet when J and I first met in our second year at University College London and went to visit his mother, I was entranced by his way with the family Labradors, Bill and Ben.

That was the end of 1967; I was 21 and in love and all was new. Everything that the 23-year-old philosophy student did entranced me: the way he hunched his shoulders in his navy pea coat, strode out in his green corduroys and whistled to those sleek black animals, his voice dipping and elongating their names – ‘Biiiiill-eee! Bennn-eee!’ – with musical authority. I was awkward and nervous as I stroked their velvety ears, making up to the dogs because I wanted to impress him – the cleverest, funniest, sexiest, most grown-up man I’d ever met. Those ‘real’ dogs seemed an extension of his capability. But I was incapable of seeing the point of his mother’s precious little dachshund.

Twenty-seven years later, in January 1994, I knew that if I chose to buy him a black Labrador for his July birthday I would have to learn to look after a dog, for the first time in my life. It was a serious decision, for since J was away a lot, the main care would fall to me. And so I, who had resolutely set my face against our son Daniel’s pleas for a dog all through his school days, finally capitulated to the reality of dog hairs, dog smells and tins of disgusting mush. I chose Billie (named by me after Billie Holliday. A control freak will even name a man’s birthday dog) and liked her, but I didn’t know how to love her. Naturally J was delighted by the surprise, and equally happy when, 18 months later, I gave him Sam, a scruffy Border collie, for Christmas. Anyone might think that I had turned myself into a dog lover, but it wasn’t true. I liked them, but that’s not enough for dogs. They aren’t satisfied with being liked. I was a dog minder, that’s all.

This is partly a story of home, for dogs know their place in the pack, and the pack needs its lair, its fastness, its refuge. In 1995 we had moved to our farm, J’s dream home, in about 60 rough acres of pasture which we would farm organically. It was a mile down a track, just outside Bath’s city boundary, and hung on the edge of a valley like Wuthering Heights, with winter weather to suit.

J briefly employed a girl to exercise his horses and one day, somehow when she was riding with the dogs near the road, Sam came home with her but Billie did not. Nor did she come for supper.

She was missing.

This was June 2002. In the warm night, pierced by the sharp cries of foxes, J roamed the fields with a torch, calling her name, fearing her stolen – for Billie-of-the-velvet-ears was a beautiful bitch. He was in despair. The next day I wrote a round robin letter, got into the car and posted my note through every letter-box within a radius of about half a mile. An hour later the telephone rang and a couple living up on the main road along the top of Lansdown (the ridge which saw one of the decisive battles in the Civil War) told me they had found a collarless black Labrador on the main road and called the dog warden. Billie was safe.

We left the house at a run and went to the RSPCA home to collect her. One of the many glorious things about dogs is that you need no proof of ownership – not really. Of course the microchip is a failsafe – but the point is, your dog knows you. When she was brought from her holding pen, Billie’s face showed relief and joy to match our own. This is something non-doggy people do not understand: the expressiveness of the canine countenance. Dogs’ faces change, just like their barks and body language; they may not be as evolved as our primate cousins but human love serves to ‘humanize’ them in the most expressive way.

Holding tightly to her lead, we saw rows of cages and heard the mournful sounds of dogs wanting to be found homes – a desire of which they could not possibly be cognizant, in the sense that we know, all too painfully sometimes, our own innermost wishes and needs. Nevertheless the desperate wanting was there in those barks and yelps, in the lolling tongues and mournful eyes of the homeless dogs, the pets who were not petted, the working dogs with no jobs. The dogs who wanted to be known as much as Billie knew us.

‘Let’s have a quick look,’ I said to J.

We wandered about, but it was too sad.

‘Let’s go home,’ J said.

So we did. Sam welcomed Billie with bounds of joy and lolloping tongue, snuffling his welcome. Even the cats, Django, Ella, Thelonius (Theo for short) and Louis, looked faintly pleased, because cats like the world over which they rule to be complete.

Then, just two days later, Lisa is entering that office with a dog on a lead, but not just any dog. My dog.

‘I have never seen such a small dog,’ I said. ‘What on earth is it?’

‘I think she’s a shih-tzu’, Lisa replied. ‘She’s in the dogs’ home. I’m keeping her with me tonight – that’s why she’s here, because I’ll go home after the meeting. These very small dogs get quite distressed in the home overnight and so if one comes in all of us take turns.’

My first assumption was that the small white dog was lost, as Billie had just been lost, but that was not the case. Lisa explained, ‘She was abandoned – left tied to a tree in Henrietta Park.’

Henrietta Park is a pleasant patch of green but very central in the city, and I simply could not believe anyone could abandon such a small dog in a place where – who knows? – drunken oafs might make a football of her.

‘Impossible,’ I said. ‘No way! Somebody must have had to rush off for a dental appointment or something, and forgotten her for a while.’

Lisa explained that it had happened two days before, and nobody had telephoned, and if the dog remained unclaimed in seven days’ time, ‘We’ll be looking for a new home for her.’

By now I had the anonymous shih-tzu on my lap, but she was eager to get off. She wriggled and looked for safety in the person who had brought her, but I was overwhelmed by a need for her to settle down – to like me. This was the magical moment of rescue.

‘I’ll give her a home,’ I said.

‘Are you sure?’

‘Quite sure.’

Looking back, I know that moments of rescue cut two ways.

I gave no thought to the muddy farm (no place for a white lapdog), or the cats (one of which, Django, scourge of rats and rabbits, was certainly bigger than this miniature mutt), or to J, a lover of ‘proper’ dogs. Real dogs. Big dogs.

Couples should discuss decisions together – I knew that. But in that second of saying ‘I’ll give her a home’ – that spontaneous, expansive welcoming of the small white dog – I knew instinctively that the personal pronoun was all that mattered. This was to be my dog. If I were to mention the idea to my husband, son, daughter, parents or friends they would all shake heads, suck teeth, remind me of hideous yapping tendencies and say it was a Bad Idea. They would talk me out of it, and this small dog would be taken by somebody else, who couldn’t possibly (I was sure) give her as good a home as I would. So I would stay silent. This was nobody else’s business. I who had never had a dog of my own because I had never wanted a dog of my own was transformed, in that instant, into a lady with a lapdog.

I knew Chekhov’s story ‘The Lady with the Little Dog’, described by Vladimir Nabokov as ‘one of the greatest stories ever written’. This tale of an adulterous love affair tells us much about human beings – but once I grew to know and love my dog I felt it showed less insight into women and dogs than I had thought. Before I am accused of trivializing a great work of literature because it lacks dog knowledge, I should point out that the mighty art critic John Ruskin was no different when he wrote, ‘My pleasure in the entire Odyssey is diminished because Ulysses gives not a word of kindness nor of regret to Argus’ – the faithful dog who recognizes him after 20 years.

Chekhov tells how a chance love affair takes possession of two people and changes them against their will. The story closes with them far apart and rarely able to meet. Gurov and Anna are both married. He works in a bank in Moscow, Anna lives in a dead provincial town near St Petersburg. Each has gone on a stolen holiday to Yalta, a fashionable Crimean resort notorious for its casual love affairs. Gurov is an experienced 40-year-old philanderer with a stern wife; Anna is married to a dull provincial civil servant, ten years older than she. The opening sentence of the story dryly establishes the holiday gossip which leads to Gurov’s interest: ‘People said that a new person had appeared on the sea front: a lady with a little dog.’

The dog is key to Anna’s identity; wherever she goes ‘a white Pomeranian trotted after her’. The dog is clearly inseparable from his mistress. Gurov’s hunting instinct is aroused. One day he sees Anna sitting near him in an open-air restaurant. Her dog growls and he shakes his finger at it. Blushing, she says, ‘He doesn’t bite.’ Gurov asks if he may give the dog a bone … and so the affair begins.

But here is also where the problems start for the lover of small dogs. A week later Anna and Gurov kiss and make love. But where is that Pomeranian? That’s what I want to know. The affair goes on – lunches, dinners, carriage drives, evening walks, bedroom intimacy – with no mention of the creature who was so inseparable from his mistress, ‘the lady with the little dog’. No dog. For all his great knowledge of human nature Chekhov understands little about ladies and their little dogs, or more specifically, the protective and possessive nature of the Pomeranian tribe. The dog would have been ever present. Those growls would certainly not have ceased, especially when this strange man became intimate with the human being the dog loved. Small dogs do not give themselves as easily as women. Easily bored Gurov would likely have been irritated by the yapping and surely suffered a nip. As a real-life lady with a lapdog, I know this. The dog could not have been written out of the narrative so easily by a man who understood.

Small dogs keep loneliness at bay for women on their own. Small dogs take you out along the promenade, because you must think of your dog, no matter how you are feeling. That Pomeranian would surely have consoled Anna when she reached out a hand in the night to curl her fingers in soft white fur, wondering perhaps if any man was worth so much pain. Or any affair.

Bonnie too was to growl at men. So great was her natural hostility to the faint whiff of testosterone, we speculated that it must have been a man who had tied her to that tree, or an unscrupulous puppy breeder who had decided her back legs were a touch too long for breed ‘standard’, or an unpleasant son whose elderly mother had succumbed to dementia and couldn’t be bothered with her pet. The novelist in me made up stories, but never convincingly, since my imagination quailed at the image of anybody tying this vulnerable young dog to a tree and walking away. I pictured the small creature straining to follow, then being choked back by the lead. Or was it a rope? I never discovered the details.

Men she might not like, yet she was never hostile to J. He was in London on 20 June when I was telephoned by the rescue home and told that nobody had come forward and so the dog could be mine. I should explain that it is policy to make a home visit to be sure that the putative owner is responsible and the place is suitable – but Lisa knew our home, knew us well, and so there was no need. In the time between ‘finding’ my dog and collecting her I had researched and discovered the ‘shih-tzu’ was in fact a Maltese, and had already named her Bonnie, after Bonnie Raitt, the singer whose music I always played in my car. This habit of naming animals after musicians (Sam was Sam Cooke, Billie, Billie Holiday) was a foible of mine; it gave cohesion to the menagerie.

I left the house at a run, went to the supermarket for unfamiliar small-dog food and straight to the home to collect her, paying them a goodly sum for the privilege. They estimated her age at six months but, other than saying she was in good condition when found, still knew nothing about where she had come from. Bonnie would never give up her secrets; I looked into her jet-button eyes and wondered who she might be missing, what kind of house she knew, what damage had been done to her. Those who study dog psychology and behaviour know that dogs from rescue homes frequently display separation anxiety – but at the time I didn’t know this. Bonnie and I were only just setting out on our journey together.

She was still my secret, not mentioned to anyone – neither daughter and confidante Kitty, nor close family friend Robin, a photographer who rented the cottage next door to our farmhouse (and with whom I occasionally worked on assignment), nor my parents – and certainly not the husband. I knew he would not want this silly scrap of a creature, and therefore need only know the fait accompli. But he was out when I called with the news, leaving me to recount my triumph to a disbelieving daughter, who was then living in our London house.

‘You? You’ve got a little dog? No!’

A day later came J’s voice on the phone – cool and faintly accusatory.

‘What’s this about a little dog? It hasn’t got a bow in its hair, has it?’

‘Not yet,’ I replied.

He did not sound pleased.

Two days later J arrived home after his Sunday political programme on ITV, arriving at the farm after the two-hour drive from London, glad to be home. As always, Billie and Sam raced to meet his car – and right from the beginning Bonnie raced everywhere with the big dogs, who regarded her with puzzled amusement. With no practice, she became part of the welcome committee. Seeing her, J dropped on his knees in his Italian suit and, as the Labrador and collie pranced around their master, held out his arms to the small dog, who covered his face with licks. That, you see, is the point about true dog lovers – those in touch with the canine spirit. They can retain no sizeist prejudice when they realize that, although the eyes are tiny and the tail is an apology for a silk whisk, the potential for devotion which characterizes proto-dog abounds in the toy. J adored her – and it took just one week of us attempting to put her to bed in the ‘dog room’ with the other dogs and the four cats, one week of hearing her jump out through the dog flap into the darkness rich with smells of foxes, badgers, owls, stoats, rats, before she wangled her way on to our bed. And this is where comfort dogs belong.

Do you believe in signs? I do, for Billie going missing and taking us to the RSPCA home was one such. And less than a month before I first saw my small dog I had met two others, who had fascinated me. For some years I had been presenting a yearly series on BBC Radio 4 called Devout Sceptics, which took the form of a one-to-one interview about faith and doubt, a searching conversation between me and someone well known in fields of literature, politics, science and ideas. In May 2002, with my producer and friend Malcolm Love, I had been in California, to interview Dr Pamela Connolly in Los Angeles, Amy Tan in San Francisco and Isabel Allende in San Rafael. On 24 May we were up early to fly from LAX to San Francisco. Coming in to land I felt that old lifting of the heart with excitement, not just caused by the eternal promise and threat of travel, but because I love the United States and always feel truly myself there.

We took a cab to the Holiday Inn on Van Ness and California, and checked in, but had no time to change, because our appointment with Amy Tan loomed. I was looking forward to the interview; I loved Tan’s novels and anticipated a good conversation about God and destiny. Having looked up our destination, in the smart, leafy Presidio area of the city, Malcolm suggested that on such a fine morning it would be good to walk there. I agreed, but neither of us remembered that San Francisco is up hill and down dale – with the result that when we arrived at the address I was flustered and sweaty, which state seemed to increase as Tan’s PA showed us into the huge, elegant condominium, furnished thickly with oriental furniture and fine objets which made you afraid to move. There was a crescendo of yapping from one corner; at the sight of us two miniature Yorkshire terriers created a tiny commotion behind a 10-inch barrier which penned them in. I gaped at the dogs – at that time, the smallest I had ever met. But they made me feel better, for when Amy Tan herself glided into the room, astonishingly beautiful in green pleated silk and soft leather ankle boots, I was able to disguise my discomfiture at being less than elegant by fussing over her pets. This much I knew – all people like to have their pets fussed over.

What I did not realize was that Bubba and Lilly were far more than dogs to Amy. We settled down for the interview and Malcolm fitted out microphones, noting with approval how quiet the condo was, the acoustic deadened by thick carpets, drapes and all that furniture. The little Yorkies nestled on her lap and Tan’s slim fingers played with their ears as Malcolm took a sound level. Then he stopped.

‘Er … Amy … I’m picking up noise from the dogs.’

‘Oh really? Doing what?’

‘Licking your hands – and snuffling. Er … do you think they could wait in another room while we do this?’

There was one of those moments of silence when the temperature drops a fraction and you know, as an interviewer, that this faux pas could spoil things. I caught the corner of Malcolm’s gaze, knowing how much he (a man of great sensitivity, especially to women) wished he could recall the impertinent suggestion.

Then Amy Tan said coolly, ‘The dogs have to stay. The dogs are essential.’

‘Of course they are!’ I cried.

Malcolm backtracked. ‘Yes, I absolutely understand … Uh … but maybe they don’t have to lick your hands?’

Pause.

‘Sure.’

The novelist kept her hands out of reach of her pets’ pink tongues, and the dogs settled down to sleep amidst the folds of her green silk, except for the occasional moment when I would intercept a beady gaze asking me what the hell I was doing there. Or perhaps sourcing that slight odour of perspiration. They yapped once during the next hour, but the interview was going so well by then it didn’t matter. And when it was over Tan (more relaxed now) told me how she hates to travel in Europe since she can’t take her dogs, how she loathes being in hotel rooms alone and how she dreads the thought of anything happening to her beloved pets. Her words intensified my impression of fragility wrapped in self-contained eccentricity.

As Malcolm and I walked to the restaurant she had recommended for lunch, I delivered myself – solemnly and with a certain degree of patronizing pity – of the opinion that those ‘teacup’ Yorkies were surrogate children for Amy Tan and her husband, Louis. Oh, statement of the obvious! What did I know? In the same way, years before when we were young, I had found some pathos in the fact that J’s elderly aunts, who lived together, posted birthday cards to each other signed from their toy poodles, Lavinia and Amanda-Jane. Later I would shake my head in disbelief on reading, in a magazine profile, that the novelist Jilly Cooper kept a picture of her dead mongrel in a locket. I was smug in my refusal to acknowledge true value in that level of affection for an animal. How fitting it was that hubris would arrive on my horizon shaped as a small dog.

Malcolm was to tease me a few weeks later, when he was editing out those yaps and one or two small dog breaths for the finished programme, and I had already fallen in love with Bonnie. He laughed that the day in San Francisco had turned me into an aspirational copycat who realized that real literary ladies must have dogs. I huffed and puffed at the joke against myself – still resisting the notion that I could be perceived as one of those women with a handbag dog.

What matters is how profoundly I’ve come to understand what it meant to Amy Tan to have those comforting dogs on her lap as talismans and as inspiration. And now it is I who, with no irony, describe myself as my dog’s ‘Mummy’. She is as necessary to me now as Amy Tan’s two were to her, and just as restricting of the impulse to travel, or even go to restaurants. I send cards from her and expect them back. Just three weeks after the encounter with Amy Tan and her dogs my diary entry reads, ‘I adore Bonnie. She has transformed everything.’

But even then I could not have known that the real transformation would be a work in progress. The dog would make me take myself less seriously – changing me into a foolish woman who would later buy a cushion saying ‘Dogs Leave Paw Prints on your Heart’ in Minnesota; a petit point of a Maltese in Portland, Maine, as well as a lobster-patterned macintosh, lead and collar set; a Navajo jacket and turquoise suede collar and lead complete with silver conchos in Santa Fe; a pink outfit in Brussels; a red set in Cape Town; cool Harley-Davidson accessories in Rapid City, South Dakota; ‘bling’ sparkles from a shop in Nice; and more. Not to mention purple mock-croc from an internet site for her bridesmaid’s outfit … but that was much later. Small-dog madness, I was to discover, is a worldwide phenomenon.

I concentrate on the trivial deliberately. These are necessarily small steps towards the big jump into that unknown which Bonnie brought with her but which was to drag me, too, into a pit of unknowing.

Smallness, I began to discover, fills some people with an irrational hatred, when they see a chihuahua, a Pekinese, a Yorkshire terrier, a Japanese chin, a shih-tzu, a pug. ‘What’s that?’ asked a young man I know when I took Bonnie to his parents’ house for lunch. Not to be outdone, his father joined in, suggesting with gentle mockery that Bonnie was ‘not a proper dog’.

‘Is the wren any less of a bird because he’s small?’ I demanded, drawing myself up to my full height (without heels) of 5 feet 3 inches.

‘Aren’t we allowed to tease you over your dog?’ he asked, dryly.

I made a measured so-so movement with my hand and the subject was dropped.

One day in Bath a pierced and tattooed man in his late twenties said loudly to his big dog, who was pulling menacingly on its string towards Bonnie, ‘Leave it! It’s not a dog, it’s a rat on a lead!’ I was filled with a protective fury which took me by surprise. This new feeling was one of many signs that I too had entered into an ancient transaction, known to all owners of small dogs throughout the centuries. What else is this but an example of Darwinian survival? Survival, of course, will gradually unfold as the subject of this book – and so it is fitting to introduce it here, in the destiny of the small dog.

Of course Bonnie, like all canines large and small, is descended from wolves and somewhere – way, way back in her genetic blueprint – a part of her soul is roaming the forests and hills, filling the night with mournful howls to others of her kind. But I admit there is little of that behavioural memory evident in the animated powder puff on my lap. Now I am her kind, the leader of her small pack, and it is I to whom she calls, in those unmistakably shrill tones. She knows I will hear, swoop, soothe, hold fast. Out there in the wild the small dog would certainly perish, and therefore it has evolved an effective method of survival: being loveable. The transaction says, ‘I will adore you and, in exchange, you – my very own human – will protect me. Where you go I shall go, when you are full of sorrow I shall comfort you, and in return you will be my shield against the world.’

Or, as Elizabeth Barrett Browning put it when she fell in love with her small spaniel, Flush, who became her consolation and saviour: ‘He & I are inseparable companions, and I have vowed him my perpetual society in exchange for his devotion.’

Those who dislike small dogs on principle sometimes ask, ‘What are they for?’ The acutely intelligent Border collie is bred to herd sheep and when not trained to do so it will neurotically round up anything it can, as if to be deprived of your function is to lose identity. Working dogs have a purpose. The veterinarian Bruce Fogle explains that the domestic dog (Canis familiaris) has the same number of chromosomes as the wolf, 78, and that over eons different canine cultures emerged. There were hunting dogs, herding dogs, guard dogs and, later, breeds to ‘flush, point, corner, retrieve, or sit quietly on satin cushions’.

Later Fogle asserts that the chihuahua ‘was bred to act as a hot water bottle’, which contains some truth – and yet I suspect that two references to cushions in his book The Mind of the Dog indicate a man whose love of dogs grows in proportion to their size. Many men proclaim a dislike of small dogs. Is the opposite of a proper dog a fake dog? Or might it be an ‘improper’ dog, carrying with it a sense of scented, snuggling, sensual, stroking intimacy, such as would make any man jealous? In the sixteenth century a clergyman named William Harrison included in his Description of England a satirical assault on women and lapdogs:

They are little and prettie, proper and fine, and sought out far and neere to satisfie the nice delicacie of daintie dames, and wanton womens willes; instruments of follie to plaie and dallie withal, in trifling away the treasure of time, to withdraw their minds from more commendable exercises, and to content their corrupt concupiscences with vain disport, a sillie poore shift to shun their irksome idleness. These Sybariticall puppies, the smaller they be the better they are accepted, the more pleasure they provoke, as meet plaiefellows for minsing mistresses to beare in their bosoms, to keep companie in their chambers, to succour with sleepe in bed, and nourish with meet at bord, to lie in their laps, and lick their lips as they lie in their wagons and couches.

I wondered, from the tone of this, if the Canon of Windsor’s wife had taken up with a toy spaniel. In fact, I find he was plagiarizing a scientific work published seven years earlier by John Caius, MD, court physician to Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth I and President of the Royal College of Physicians. Our Western concept of breeds was first recorded in his Short Treatise of English Dogges in 1570. In this useful work I meet Bonnie:

There is, beside those which wee have already delivered, another sort of gentle dogge in this our Englishe soyle … the Dogges of this kind doth Callimachus call Melitoeos, of the Island Melita, in the sea of Sicily, (which this day is named Malta, an Island in deede famous and reoumed …) where this kind of dogges had their principall beginning.

He continues, ‘These dogges are little, pretty, proper, and fine …’ and so on, although the magnificent phrase ‘Sybariticall puppies’ is the Revd Harrison’s own. Dr Caius goes on to make a perceptive point about lapdogs, which I would not have been able to understand in 2002, when Bonnie was so new, as I do now. Criticizing a female tendency to delight in dogs more than in children, he guesses at mitigating circumstances: ‘But this abuse peradventure reigneth where there hath bene long lack of issue, or else where barrenness is the best blossom of bewty.’ The small dog as child substitute? Of course – for there are many ways to save a life, and this is one to which I shall return.

That summer we took Bonnie to stay on our new boat, a Puget Sound cabin cruiser which was moored at Dittisham, on the river Dart in Devon. J bought the dog a tiny ‘pet float’ and each morning he would rise early, dress her in her red life jacket and row to the shore so that she could relieve herself. My lack of rowing skills was a good excuse, but in truth, he never once complained. I would stand on deck and watch him, remembering our honeymoon in that very village (so cold in February 1968, while this July gave us the hottest day of the year) and loving the fact that he was so at home on the water which scared me, a non-swimmer. By now he loved my dog; why else would he have agreed that she should come on holiday while Billie and Sam and all the cats remained behind on the farm, taken care of by my father? The dog came everywhere with us and when, after a few days, I developed an inexplicable pain in my right arm, my daughter suggested it must be a repetitive strain injury, caused by clutching Bonnie so tightly. Of course.

Bonnie was sitting between us as J and I heard Devout Sceptics broadcast at 9.00 a.m. on Radio 4, Amy Tan’s voice filling the cabin as the waves made their soft slapping sound against the blue hull and J listening with his characteristic intensity. I imagined those tiny Yorkies on her knee, her long fingers held carefully out of reach of their tongues, as she talked about her belief that there is a benevolent spirit in the world, larger than any individual. ‘That works with the concept of a god,’ she said – and went on to link it with the idea of, not so much forgiveness in the Christian sense of the word, but compassion. Her voice was quietly firm as she told me that her aim was to learn about ‘this notion of compassion’, about empathy with her fellow human beings – which she defined as ‘another way of saying Love’.

She added that of course you cannot measure love – it cannot be scientifically proven, no more than the idea of an afterlife. Yet she could say, ‘Yes, I believe this,’ because she finds ‘intuitive emotional truth’ in the idea each day of her life and in the writing of her novels.

As I re-read her words today (the interview was printed in my book, Devout Sceptics) I realize how much Amy Tan’s philosophy informs my own life, and that the meeting with her and her small dogs was significant in more ways than one. Everything that has happened to me since Bonnie arrived from nowhere has at once tested and confirmed it. What’s more, the entirely serious lessons my little dog has taught me confirm her optimism. There is no doubt in my mind what small dogs are ‘for’.

But it was still so new. My diary entries record the process of dog intoxication – for that is indeed what it was. As the American genius Amy Hempel wrote in her short story collection The Dog in the Marriage, ‘… you don’t just love the dogs, you fall in love with them.’ In the summer of 2002 I wrote in my diary:

27 June – Bonnie has transformed things. She is so sweet I want her to be with me all the time.

3 July – I find it hard to concentrate on the novel because I spend too much time fussing over Bonnie.

23 July – Bonnie continues to delight me. It is a strange feeling – to love a dog.

Bonnie fitted easily into the Devon part of our life, although some of the old friends teased the lady with the lapdog. I suppose I can understand, because it was so unexpected to see me in that role; nevertheless we must all allow people to change. And I had changed. Instead of being impatient on the boat and feeling marooned I relaxed, strolling with the dog and gazing at the water, soothed by the ceaseless pinging of rigging in the breeze. Looking back, that summer seems idyllic. Robin had rumbled into the village on his Harley-Davidson, and joined us on the boat. Our son Daniel arrived, tense but liberated at the end of a long relationship. Kitty’s boyfriend left early and she was upset. We spent time with the grandparents, I cooked meals in the boat’s small galley, J took care of Bonnie’s needs … and so family life went. From the time they were babies our children had loved that village, the scene of our many shared family holidays, not to mention our honeymoon.

The weather was hot, but a sudden squall disrupted J’s birthday celebrations on the last day of July. No drinks on the boat for family and friends, but dinner in the local café for a pile of us. My diary records, ‘The wine flowed and the noise rose and Bonnie sat on my lap and I thought how lucky we are to have all these talented, interesting and deeply kind Devon friends. It was a fabulous night.’ On another evening we joined friends for a beach barbecue. Suddenly fireworks from a celebration up the river filled the sky with falling flowers and stars and ‘illuminated the evanescence of it all’.

The year 2002 marked the jubilee of Her Majesty The Queen. The country which had in March confounded all republicans by mourning the death of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother joined in celebration of the fifty-year reign of her daughter. J and I had watched the London procession on television. We are both monarchists: my grandmother cleaned houses for a living and served lunches in a girls’ school, yet the Royal Family was part of her sense of identity, like her quiet belief in God and love of her family. She liked to show me pictures of the young Prince Charles and Princess Anne, cutting them out of the Daily Mirror. She liked the smart woollen coats with velvet collars and buttons worn by the children of the upper classes.

In contrast, J’s father, Richard Dimbleby, was an icon for my grandparents’ and parents’ generation: the most famous broadcaster the country had ever known, revered by the public first for his fearless war reporting, for his shocking, shattering dispatch as the first journalist into Belsen, and then for his commentaries on great events (the funerals of George VI, Sir Winston Churchill and John F. Kennedy and the coronation of Elizabeth II) when the poetic dignity of his spoken prose expressed the deepest feelings of the majority of British people. When I first met the philosophy student (two years after his father had died) and told my parents I was dating ‘Richard Dimbleby’s son’ they were awestruck. It was hard for me to believe too.

From different worlds we came, J and I, meeting in the second year of our respective courses and marrying after just three months, so much in love there was nothing else to do. It was just like fireworks – and naturally the years of married life would whoosh, crackle and bang too, sometimes so dangerously. Yet those first flames still had the power to warm, and the showers of stars still hung in the sky, even if sometimes behind clouds.

In 1994 he had published his much-admired biography of the Prince of Wales, a considerable achievement which came not without stress – largely due to the fact that J’s simultaneous two-hour documentary about the Prince on ITV had included a short admission of adultery. The world seemed to go mad. J, a political journalist who was initially dubious about taking on the Royal project, knew that he had to ask the Prince about the state of his marriage to Princess Diana and his relationship with the then Camilla Parker-Bowles. He felt that the boil of sleazy gossip and tittle-tattle had to be lanced – and so, under firm but gentle questioning, the Prince revealed to the watching millions that once his marriage to Diana had irretrievably broken down he had started a relationship with Camilla. He would have been damned if he hadn’t but was damned for telling the truth. At the same time, many people said that J ought not to have asked the question, although had he not he would have been pilloried for failing to do his journalistic job.

It was an exhausting time. Side by side we faced it all down but, seasoned journalists as we both are, we were unprepared for the tabloid feeding frenzy and the level of vitriol that was unleashed upon the heir to the throne – a much-misunderstood man whom J called in the closing words of his biography ‘an individual of singular distinction and virtue’. I recall J standing in our garden or sitting in the library at the farm doing endless interviews with CNN, ABC, Sky, etc. and for a while it seemed as if he was almost the only one who would analyse and interpret not just the Prince of Wales but the British monarchy to the rest of the world. Although he did it with cool insight it was not a role he relished – not at all – but it was to be repeated after that terrible day at the end of August 1997 when Princess Diana died in a car crash in Paris with her lover, Dodi Fayed.

Looking back, the era of his biography and TV documentary seems oddly innocent. It is astonishing to remember that the Prince of Wales had wished to protect his estranged wife by not revealing all the detailed information J had in fact discreetly accumulated about Diana and her many problems. A few years later a slurry of cheap, gossipy books, prurient television programmes and mean memoirs by seedy staff would ensure no compassion or respect whatsoever for the dead Princess or for her living sons and ex-husband. Britain was turning into a pit bull of a nation.

The Prince loves dogs and in J’s documentary one of his two Jack Russells appeared, jumping about in a Land-Rover as Jack Russells will, and being told in no uncertain terms, ‘Get down, Tigger!’ Tigger had puppies; one went to Camilla Parker-Bowles and the Prince kept another, which he called Roo but Prince William renamed Pooh. In April 1995 Pooh vanished at Balmoral. This became an instant news story, the animal-loving British public responding with all the interest a beloved lost dog deserves. Jilly Cooper wrote a heartfelt piece about ‘poor little Pooh’ in the Daily Mirror, while the Daily Mail ran photos of the dog captioned ‘Pooh: loved and lost by a prince’. The Jack Russell had been on a walk with her owner and her mother, when she ran off into the woods. Charles’s whistles brought no response, and a three-day search by estate workers was fruitless. Neither an advertisement in the local paper nor the Daily Mail’s offer of a good reward brought forth anyone who had seen the dog. As a heartbroken Prince headed back to London on 21 April there was no shortage of theories about Pooh’s fate. Some suggested that the dog had become stuck in a rabbit hole, as Jack Russells will, while a psychic asserted that she had ‘a very clear picture’ of Pooh stuck in a sewer. The News of the World gleefully theorized that she was devoured by a feral cat dubbed the Beast of Balmoral.

Such a fuss about a dog. Yet the true dog lover – the person I was metamorphosing into in 2002 – understands it. Once you love a dog you cannot bear the thought of losing your pet and you will torment yourself imagining your dog being kidnapped, or dying. No wonder the Prince of Wales put up a memorial to Tigger at Highgrove, when, in 2002, his beloved dog had to be euthanized because of old age.

That same year, Bonnie accidentally went to Highgrove and met the heir to the throne. For most human beings this would have been exciting, but it was quite an event for a nobody, a dog from nowhere who, just months earlier, had been left tied to a tree – a progression surely worthy of Eliza Doolittle. Yet like Eliza, she took it in her small stride.

Needless to say she had a royal welcome.

For centuries the Royal Family has embraced dogs as their favoured pets. Formal portraits from the seventeenth century onwards show kings, queens and their children happily posing with their beloved animals, from pugs to greyhounds, King Charles spaniels to corgis. Although we associate the British aristocracy with hunting dogs, big dogs with a serious role in life, the Royal Family has always loved smaller hounds too. Some pets have even merited their own portraits, and (as in many households) were considered members of the family. Photographs from the Royal Collection prove how much dogs were valued. A photograph of Queen Victoria’s son, the Duke of York, shows him with his pug and is full of a playful humanity we can all recognize. The dog is wrapped in a greatcoat and its royal owner has tied a handkerchief around its head. The dog looks at the camera, the Prince looks down at the dog, full of mirth.

In 1854 the total cost of photographing the dogs in the Royal Kennels and mounting the prints in a special handsome album came to £25 19s. – the equivalent of around £1,650 today. When Queen Victoria’s beloved collie Noble died at Balmoral in 1887, he was buried in the grounds of the castle and given his own gravestone, which reads:

Noble by name by nature noble too

Faithful companion sympathetic true

His remains are interred here.

A terrier named Caesar belonging to Edward VII was given even greater status when, having outlived the King, he walked behind His Majesty’s coffin in the funeral procession.

Elizabeth II favours the corgi. The breed was introduced to the Royal Family by her father, George VI, in 1933, when he bought a corgi called Dookie from a local kennels. The animal proved popular with his daughters, so a second corgi was acquired, called Jane, who had puppies, two of which, Crackers and Carol, were kept. For her eighteenth birthday, the Queen was given a corgi named Susan from whom numerous successive dogs were bred. Some corgis were mated with dachshunds (most notably Pipkin, who belonged to Princess Margaret) to create ‘dorgis’. The Queen’s corgis travel with her to the Royal residences, and Her Majesty looks after them herself as much as possible. Other members of the Royal Family own dogs of various breeds. The Duchess of Cornwall owns two Jack Russell terriers, Tosca and Rosie.

The day Bonnie went to a Royal residence the country was tossed by storms, with gales of up to 90 mph which screamed around our farm on the hill. Branches cracked from the beech wood and the trees groaned as if in agony. In my diary I wrote, ‘I feel overwhelmed by all I have to do, but Bonnie is such a consolation’, but on that day it was hard to walk out with the three dogs and not be blown sideways by the power of the gale. Looking at Bonnie you would have thought she could be blown away, like a tuft of thistledown.

Earlier in the week we had been at the Booker Prize dinner, to see the outsider Yann Martel awarded the plum for The Life of Pi and to mingle with peers and swap gossip. When at such events I always feel two people: one at home within the glitz, the literary glamour, but the other detached, wanting to be at home – especially once the Maltese came to stay. The diary captures this feeling, recording, rather than a desire to be in London, ‘I want to be home to see Bonnie. The little dog ties me to the farm emotionally more than ever.’ I also wrote, ‘Home, home, home’, with no explanation, as if the repetition of what gave me security would fix it for ever. Now I see that scribble as a litany of faith. It was the only faith that possessed me completely.

On Sunday night J and I were due at Highgrove for dinner, and our friend and neighbour Robin offered to drive us. The journey is only 35 minutes’ drive from where we lived, yet it would have been less than convivial for J to refuse a glass or three of wine, and even less wise to exit past the policemen having done so. So we left the dogs and barrelled along past fallen trees to arrive at the handsome Georgian house, just outside Tetbury, in Gloucestershire. I loved going there. The house is not overly grand; nor does it have an intimidating atmosphere. From the hats, boots and baskets at the entrance to the comfortable furniture which sometimes bears the marks of dogs (I remember an old chintz that had been shredded and was waiting repair) Highgrove is a genuine home, full of family photographs and treasured mementos.

Camilla was driving herself from her own home, and was late. The Prince fixed us drinks from the trolley, and as always I sensed a hunger within him to talk to someone like J about the issues he cares about: agriculture, the environment, education and so on. As on many previous visits he seemed strangely lonely: a good man marooned in a difficult role, frequently misunderstood and feeling it too keenly for his own good. At last Camilla blew in like a gust from a rather more robust world. My diary observed: ‘She is warm and full of mirth – rejoicing that the Panorama programme about her is on TV tonight but she doesn’t have to watch it because she is with us!’ While the men talked about serious things she and I perched on the leather fender and smoked a cheeky cigarette, puffing the smoke up the chimney as we chatted.

It was a good evening – and when the time came for Robin to pick us up, we were surprised to see Bonnie scamper into the room. With advance warning from the gate the staff had opened the front door and in she went – small dogs do not stand on ceremony. Robin told us later he hadn’t had the heart to leave her behind, since she made such a pathetic fuss as he put on his coat. Astonished by her size (very small compared to a Jack Russell) the Prince and Camilla gave her maximum attention and were fascinated by her story of abandonment and rescue. Camilla’s elderly, almost-blind terrier smelt the sweet young female and noticeably perked up, chasing her about. Bonnie responded flirtatiously and, vastly entertained, the Prince roared his contagious, bellowing laugh of which Falstaff would have been proud.

On the way home J and I agreed how much we liked ‘doggy’ people. At last I was including myself in their number.

The Royal Family’s traditional affection for dogs might well be an antidote to the fuss that surrounds them. The Prince of Wales is, to his dog, just an owner, a human companion who offers treats and strokes and is always ready to stride out into the indescribably thrilling grass and trees. The dog is always there, always loyal. He will not sell his memoirs; nor will he bite the hand that feeds him. There are no complications; the dog does not have to say ‘sir’ or bow, and yet he will obey. I can imagine the Prince striding over the countryside he loves and telling a dog everything, knowing that whatever he says will never get back to the newspapers, nor be captured by any paparazzo’s telephoto lens.

I would be telling lies if I told you that at this stage in my life I looked at my small white lapdog and saw in her a teacher. Yet I should have done, for the lessons were already beginning. For example, one day I hit her – for the first and last time. It was not a savage blow. The big dogs would not have noticed such a swat and the cats would have easily avoided it. But a padded envelope arrived containing a copy of my latest children’s book – the first off the press. It is always an exciting moment for an author – that pause of satisfaction when you hold the fruit of your labour in your hand, look at it, admire your own name and think, I made this. That day I had put the book down on the futon in my study, gone to make coffee and returned to find that the young dog (less than one year old after all) was chewing the corner of my new book. And so I picked it up, swatted her and yelled, ‘No!’

I did not know (neophyte that I was) that ‘No!’ is the cruellest word you can shout at a dog, even if sometimes you must. Nor could I have predicted that she would shrink back, raise just one paw as if for protection and shiver with terror. The lesson I learnt that day, as I cried with remorse and bent to cuddle her, was how quickly she could forgive. She licked me as if to say she was sorry, it was all her fault, it was all right, I shouldn’t upset myself any more, all was well. There were no sulks. The tiny creature was bigger than I could have been – and I was astonished. Much has always been written about the fidelity of the dog, and yet this quality of forgiveness should not be underestimated.

Saturday 12 October was beautiful. The sun glittered on the pond, where water spurted into the air from the spring swollen with autumn rain. The trees in the beech wood had crisped to russet, and the silver birch by the pond was weeping gold, like a metamorphosed princess in myth. J and Robin decided to go logging on our land, ready for winter. The big dogs raced, because they liked nothing else than to be down in the rough fields, smelling rabbits, foxes and badgers and rolling in mud. As always, the cats glided around on the perimeter of the action. But I had to leave the gang and drive the one hour to Cheltenham to take part in a discussion on marriage at the Literature Festival. As I backed my car from the car port I saw J scoop Bonnie up, then turn with her in his arms to tramp down to where the tractor waited in a gilded landscape.

I had contributed to a short book called Maybe I Do: Marriage and Commitment in Singleton Society, published by the Institute of Ideas. Over the years, as a prolific journalist, I have written many thousands of words on this subject, and in 1989 I compiled an anthology of poetry and prose about marriage. It had started as a silver wedding present for J, but ended by being published and dedicated to him. We had perfected a double act: reading a selection from the book at festivals and for charity. I liked being married and saw (as I still do) the institution as the bedrock of society – although with no illusions about how difficult it is. ‘The greatest test of character any of us will have to face,’ was how I described it in my anthology introduction.

Now a group of us were gathering to discuss marriage before a sold-out audience in the Town Hall in Cheltenham: the novelist Fay Weldon, journalist and novelist Yvonne Roberts, radical journalist Jennie Bristow, Claire Fox from the Institute of Ideas (my publisher) and me. It was a good, wide-ranging discussion and as usual I was the most conventional of all the speakers, banging a drum for what I truly believe in: the importance of stable marriage to the upbringing of children. That is, when it works. My chapter in the book was called ‘For the Sake of the Children’ and ended with these words – which sum up the essence of my platform contribution:

Of course marriages go wrong, but I do not believe anybody has the right to put their own needs/feelings/wants before those of their children. Most of us could have skipped out of our marriages at some time or other, in pursuit of romance – by which I mean, fresh sex. ‘Staying together for the sake of the children’ became a much derided mantra, but I see it as a potential source of good. Who knows – by putting Self on the back burner, many a married couple may find they weather the storms and ease themselves into the best of friendships, to share old age together, in married love.

Now I regret the trite cynicism of that phrase ‘fresh sex’ but admit that the last sentence is pure autobiography, not theory. It was where I thought we both were, what I most wanted.

That night we went to a dinner party near Bath. Beautiful converted barn decorated with impeccable taste. Schubert floating through the scented air. Logs roaring in the wood burner. Excellent champagne, cold and biscuity in tall glasses. So many people; we didn’t know them all. Such a buzz. Conversation about the arts amongst (mostly) practitioners. Delicious food cooked and served by our perfectionist writer-hostess and free-flowing wine to match its quality. The long, long table, lined with merry faces, as the laughter rose to the ceiling.

How many such evenings had we enjoyed, by the autumn of 2002? How many people had we met, talked to, flirted with, become friends with, forgotten in time? Both social beings, J and I always enjoyed gatherings where conversation was sparkling yet unstuffy – and this one was one of the best. He was sitting at the opposite end of the long table, between our hostess and a blonde woman whom I had not noticed during the pre-dinner drinks. I did not even notice her face in the candlelight; she was too far away. And why indeed would I notice? J and I had come too far together to fret that the person next to one or other of us at dinner might come to mean something.

Yes indeed, the moments do come when the universe smiles and plays a trick. Yes indeed, you get up one morning with no inkling that the day will bring a life-changing moment. The face of a future lover seen across a room, a sudden stumble which leaves you with a black eye … There can indeed be no knowing what will pop out from under the lid of the scary jack-in-a-box, to shake the foundations of the world you know. As we drove home, exchanging details of conversations and swapping gossip and opinion as we always did, J told me about his neighbour at dinner. He liked her a lot but was, he confessed, slightly bothered because it turned out she was a very well-known opera singer, just making her mark on the international stage, and yet he had not heard of her. Nor had I.

Her name was Susan Chilcott.