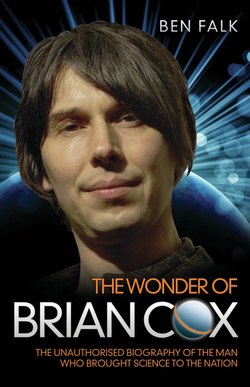

Читать книгу The Wonder Of Brian Cox - The Unauthorised Biography Of The Man Who Brought Science To The Nation - Ben Falk - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

DARE TO WIN

ОглавлениеIt’s not every day a rock star moves in round the corner from your house, especially if you lived near Oldham in the mid-1980s. So, word spread quickly when Darren Wharton, former keyboard player of legendary rock group Thin Lizzy, took ownership of a property close where Cox and his family lived. Not only that, but Wharton – a curly-haired, handsome man in his early- to mid-twenties – began drinking in the same pub as Brian’s father and before long, the former Lizzy-ite knew about the teenage Cox and his musical aspirations. We need to back up a bit first, though because the story of Dare, Cox’s real musical interlude from science and the band which almost deprived the BBC of its face of physics, starts a couple of years earlier.

Lancastrian Darren Wharton was a keyboard player and songwriter who as a teenager had been discovered playing in Manchester nightclubs and was recruited by legendary rock’n’roll band Thin Lizzy to play in one of their latter incarnations. But as Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott’s addictions took hold and the group disintegrated around 1984, Wharton found himself back in his hometown of Chadderton near Oldham, in a nice 18th-century farmhouse purchased from the proceeds of various rock records. Keen to make the transition to frontman and singer, Wharton turned down offers from other groups and signed a deal with Phonogram records as a solo artist. Following this, he set about putting together a band. He found lead guitarist Vinny Burns through a friend and the pair worked on material for about six months before beginning to sign up other members. Working under Wharton’s name, they hired Ed Stratton on drums and a BBC sound engineer with the single moniker Shelly on bass. They took photos and began rehearsing, but then Wharton’s deal with Phonogram fell through and the band found themselves without record company backing. Stratton was sacked – he didn’t get on with Shelly and also lived far away from the other guys in Northampton – and local lad Jim Ross drafted in on drums.

Wharton was also keen to change the band’s name to something else. While at Donington, he bumped into Lemmy from Motorhead and confided in him. Lemmy suggested Dare 1. Wharton didn’t like the numeral, so dropped it and Dare was born. Burns and Wharton continued to write and record songs, doing a deal with a studio in Manchester whereby they would play for free on radio idents and jingles; in return, Dare would get to record or rehearse in the studio. Until now, Wharton had been singing from behind a keyboard, but he now wanted more freedom of movement and decided to hire a second keyboard player, while using Eighties staple the keytar (Wharton’s version, which he fashioned himself using lashings of gaffer tape was dubbed ‘The Batmobile’). A youngster called Mark Simpson was hired and the band, which was starting to pick up momentum locally, continued to gig furiously. Record companies began to take an interest and Chrysalis were potentially keen to sign them; the band travelled to London for a showcase but the head of A&R at Chrysalis wasn’t interested. They recorded several demos and found their manager, Keith Aspden after he was introduced to them by someone who worked in that studio. However, the band ended up going their separate ways.

It was 1986 and Brian Cox was getting ready to go to university. He would drive around in his souped-up Ford Fiesta, listening to the music from Top Gun until he hit a lamp post and got charged for it by Oldham Council. He began listening to something more sedate. Aware of the rock star living round the corner and with a decent grasp of the keyboards, he had dropped a tape round to Wharton’s house a couple of years before. More importantly, Cox’s dad went to the same pub as the singer and had been round to his house a few times. ‘They talked about music,’ says fan Mick Taylor, whose love for the group led him to become head of the Dare fan club. When Mark Simpson left the band, Wharton remembered the tape he’d received and asked Cox Sr whether his son still played keyboards. With his spiky hair and sharp cheekbones, Cox certainly looked like a rock star. ‘I would say without a doubt Brian was the best-looking one,’ recalls Taylor. ‘You only need to look at pictures when he was in Dare and he was the heartthrob – he stood out like a sore thumb. My ex-missus said he was the best-looking!’

Wharton offered Cox – five-and-a-half-years his junior – a place in the band. Though he still had dreams of being a scientist, the 18-year-old didn’t think it would be too bad to take a year off and give rock stardom a go. It turned out to be a lot longer. ‘You don’t miss physics when you’re 18, in a rock and roll band,’ he once reminisced. Surprisingly, his parents didn’t mind the diversion. ‘They were actually really supportive,’ he told Radio 4. ‘They loved watching us live. They came to Manchester Apollo to see us and really enjoyed the process – I think they were quite upset when the band split up and I went to university. I think they enjoyed their time in the rock and roll sun.’ The Maple Squash Club in Oldham, near the football ground, became the band’s home from home. They knew the owners, Allan and Rita, who let them rehearse free of charge and soon they had a Saturday night residency at the venue.

‘We used to go every week,’ remembers Oldham resident Tony Steel, an early Dare follower. ‘We got hooked. It was before the first album, so they used to do all the stuff from the first album at the gigs.’ Steel is just one of the many fans who fell in love with the group from the start. ‘It was quite a small room, quite a low ceiling,’ he says of the Squash Club, which held about 100 people. ‘It was a bar/restaurant – very close, very personal. It was a great atmosphere, because it was rock, but you could hear the music and the words they were singing.’ The audience tended to be around the same age as the band and despite the loud music and the alcohol on offer, there wasn’t any fighting. ‘It was the same people, week in week out,’ says Steel. ‘[The band] brought their friends. It was the same faces. Then it grew a little bit each week to the point where if you didn’t get there by eight o’clock, you didn’t get in.’

The gigs were where the band honed their stage act. ‘Darren was confident because he had toured all over the world,’ recalls Steel. ‘Brian was a bit shy because he was the youngest one. He didn’t tend to speak – he stood in the back, hiding behind his keyboards. I remember him being quite shy compared to Darren Wharton and Vinny Burns. You could tell [Brian] was doing most of the keyboards. They all did little solo bits and you could tell he was actually playing it. He wasn’t just in the background for shows. He had long hair at the back and spiky on top. Not like punk spiky – the whole top was spiked up, a proper mullet – the usual Eighties band thing.’

Cox himself remembers ‘long hair, hairspray, ripped jeans, leather jackets…’ He would become transfixed watching Wharton cover himself in what he thought was chip fat before shows. ‘He used to grease himself up and run around!’ he laughed. ‘We were very Eighties.’ Unlike many of the acts in those days, the keyboard set-up was pretty small. Some of this was to do with the fact they already had two keyboard players but also because they couldn’t really afford any equipment. Shelly had to borrow a bass before every gig. It wasn’t until their record deal that they could splash out on new gear and any fees collected from the early shows were used to pay for a van to travel to the venues. Sometimes they even had to resort to dubious means to get around the transportation issue. ‘When I first started publishing a fanzine for Dare, I advertised it in the music papers,’ explains Mick Taylor. ‘Not long afterwards, I got a letter that had been sent from Her Majesty’s Prison Strangeways in Manchester. It was from a loveable rogue called Ian McGiffen, who introduced himself as Dare’s road manager. He had got himself into some trouble, so was temporarily unavailable!

‘Ian has sadly passed away now, but he told me that one day he was on tour with Dare and they were due to travel to a gig one night but their van had broken down; they were stuck. Ian was one step ahead and told the guys not to worry. A couple of hours later, he turned up with this van saying he had borrowed it from a mate but had to have it back the same day. The guys loaded up the van and off they went. After the gig had finished, Ian dropped everyone off and took the van back to where he had stolen it, ha ha! Little did the band know they were travelling around in a stolen van! Ian was very proud of his time with Dare and Darren later wrote a song with him in mind called ‘Breakout’, which was on the band’s second album, Blood From Stone.’

The Maple residency lasted almost 18 months and meanwhile the band continued to increase their following around the northwest. Cox dubbed them the ‘Oldham Bon Jovi’. They had a small crew, including Burns’ brother Russ and Ian McGiffen, and the shows were beginning to feel slicker, with good sound and a quality light show. In fact, they even managed to swing a 12-day tour of Hong Kong after a photographer friend lied to a promoter about who they were. It was only the second time Cox had been abroad (the first was a school ski trip). They did some gigs and appeared on a local TV show before heading back, where they were greeted with increased record company interest. It was the first time Cox appeared on television, smiling shyly from behind his keyboards. Amazingly, it looked like his dreams of becoming a rock star might just come true – and sooner than he thought.

‘I wouldn’t say it was dead easy,’ says Mick Taylor, but by all accounts three companies were fighting to land the band’s signature. EMI came to see them at a gig in Oldham and then MCA checked out a concert at the Maple Squash Club. RCA and A&M got wind that both labels were interested, so immediately headed up to watch the group perform the following week. Convinced they had found the next big thing, A&M told the boys to forget the rest and drew up an eight-album deal. In May 1987, Cox was a member of a band with a record deal and any ideas of becoming a scientist would have to be put on hold.

Though Dare had acquired a reputation as a formidable local live act, all they had to show for it as far as recordings went were some demos. ‘It was before mobile phones, so you couldn’t record it and play it back as you could do now,’ explains Tony Steel. There were live bootlegs kicking around, but not many. A&M were keen to get an album in the bag and into the shops, so they introduced the lads to Mike Shipley and Larry Klein, the duo who would produce their first album. Shipley was an Australian who had moved to Los Angeles in 1984 and worked with hundreds of acts as a sound engineer, including AC/DC and The Clash. Klein was a former session bass player, who had married folk singer Joni Mitchell and moved into producing. Dare had plenty of tracks ready to go – in fact, they already had the core of their first record. In January 1988, they all piled, hungover, into Cox’s Ford Fiesta and headed off to Hookend Manor in Berkshire, a mansion formerly owned by Pink Floyd’s Dave Gilmour that had since become a favourite recording haunt of music labels. They laid down some tracks, but the producers decided they needed to finish off the album in LA, so the band headed out there. It didn’t take much persuasion.

They stayed at the Sheraton Miramar in Santa Monica and recorded at Joni Mitchell’s property in Bel Air. ‘It was really fantastic,’ recalled Cox. But it wasn’t all rock’n’roll. During a day off, the band decided to visit Disneyland, south of the city. They drove their hire car down there and parked it in one of the huge parking lots. After enjoying the rides, they returned to pick up their car, only they couldn’t recall where they had parked it. Remembering the area for parked cars was the ‘size of Leeds’, Cox has said: ‘all we knew was that it was red!’ He added: ‘We had to wait until everyone had gone home and there was nothing left in the parking lot. And then they drove us around until we saw a red car. We had to wait until about midnight. That’s rock and roll, isn’t it? Lost in Disneyland!’

In those days, it was also crucial to make a video to accompany a single and with ‘Abandon’ chosen as the first song to be released off the debut album, the band returned to Los Angeles in August of the same year to shoot the promo. It was filmed in South Central LA, a down-at-heel part of downtown (especially so in 1988) and features the group rocking out against an industrial backdrop and lots of dry ice. Somewhat inexplicably, a sexy young woman (actually future Twin Peaks star Mädchen Amick, who would go on to become a successful TV actress in particular) meanders about, showing off her cleavage before climbing into a fancy car, supposedly having been abandoned. The video ends with the guys walking off into a smoke-filled distance. Cox doesn’t get all that much screen time as it is mainly focused on Wharton and Burns but there’s a moment when he can definitely be seen grinning. Considering what he might have been doing at the time had he not been shooting a rock video, it’s unsurprising.

A&M unveiled the band before the press on 25 October 1988 at The Marquee Club in Soho. As this was the group’s debut London show, they were understandably nervous. It wasn’t helped by a poor sound mix, which often drowned out the vocals. The record company were careful to mix the media in with a group of supporters from Manchester, so that it wasn’t simply an anodyne showcase. Journalist Valerie Potter – a self-confessed Dare fan – was there and wrote: ‘The band were obviously rigid with nerves and this made their performance a little shaky until they got into their stride. Nevertheless, I still stoutly maintain that this band is one to watch for in ’89. Second keyboard player Brian Cox puts in some sterling support from the back of the stage. There are still some rough edges that need to be smoothed away by regular gigging, but now that Dare have leapt over the hurdle of the “debut London show”, on their next London appearance, I think they’ll show us what they can really do.’

The band thought they had done a decent job. Vinny Burns later wrote: ‘We played it very safe and it felt more like being in a goldfish bowl than any of the other good Marquee gigs that we would play later on. The press seemed to go on more about the fact that A&M had done an over-the-top free bar for guests – we couldn’t even get served with free drinks ourselves, it was that packed. We knew we would be footing the bill for it all in the long run; we made sure that didn’t happen again. Still, it was good to play the Marquee and it was a good gig, too.’

‘Abandon’ was the first single to be released but it didn’t do very well, only reaching No. 99 in the charts when it originally came out (it spent two weeks getting to No. 71 when re-released in July, the following year). It had a couple of champions, though and for the fans, this felt like the start of great things. ‘It was a real shock to the system first time we heard it on the radio,’ remembers fan Tony Steel. ‘We started hearing it on Radio 1. There was a teatime DJ, Gary Davies. I remember him saying he was going to play something from a new band and it was one of the best intros he’d ever heard. That was “Abandon” and it is a fantastic intro.’ The fact that they were a local band made good made it all the more special for those who had been there right from the beginning. ‘It was like, “I know these, I used to go and watch these,”’ adds Steel. ‘It was quite a proud moment in that we’d helped them get there. If we hadn’t gone to watch them, they would have never made it – we felt part of the success.’

And the fans weren’t the only ones who were shocked. ‘Obviously there was a big fuss about him joining the group and having a single coming out,’ says school friend, Tim Haughton. ‘At the time, everyone thought it was a load of bullshit, to be honest with you. Everyone thought he was just talking it up and it would never happen, blowing his own trumpet. And then obviously it happened and everyone was like, “oh my God, he’s telling the truth!” One thing you’ve got in a school like that is you’ve a lot of intelligent people, there’s a lot of egos involved – you couldn’t go a week without someone starting a band, but a week later it had all dissolved into nothing. So, when someone says “I’m in this band, we’re going to be bringing a single out, we’re going into the studio and recording some songs”, everyone goes “yeah, great, what a lot of bullshit!” When it actually happened, everyone was gobsmacked.’

The album, titled Out of the Silence, was released not long afterwards. Because of a quirk in the Gallup charting system, which said only certain stores were counted as being valid for sales, it didn’t make the charts. Fans have pointed out that 89 per cent of the LP’s sales came from the Greater Manchester area and sometimes it was selling up to 300 copies per day. If that was the case, it would have been a Top Five record. It received positive reviews from the music press, with Jon Hotten in heavy metal bible Kerrang! giving it four and three-quarter stars out of five. ‘Dare have everything,’ he wrote. ‘Songs, instrumentation, production, but most of all they have that indefinable X ingredient that sets them apart and above the rest. Take “Abandon”, build around rich keyboards and vocal hooks that will tear you apart, but the album’s high point is without a doubt “Under the Sun”, a supreme example of dramatic atmosphere and how to create it around a lilting, minor-key piano accompaniment. Dare are there to be awed and AOR fans will lap it up. As a genre piece this excels and I love it. Don’t miss it.’

Elsewhere, the keyboards parts were described as ‘shimmering’ while another critic added: ‘the keyboards and guitars blended together nicely’. The album went Top 20 in Sweden and Cox’s youthful looks were noticed by some writers: ‘The man with the perpetual grin and baby face, which makes me wonder if he’ll ever start shaving,’ scribbled one hack. During live shows, Wharton continued to play his keytar, mainly because of the rich keyboard sounds on the album. ‘It was either that or use tapes,’ he told one magazine. ‘Brian couldn’t physically play what was on the album alone.’ Some articles go so far to suggest that Cox mostly played the rhythm lines on the record, while Wharton did the majority of the lead solo work. Certainly he did some solos while onstage, but it’s clear Cox did pull his weight. ‘It was more Darren and Vinny who wrote the songs,’ says fan club chief and aficionado Mick Taylor. ‘But I did go to watch them in the studios once, I think it was called The Greenhouse Studios, when they were rehearsing. You’d get Brian adding a little keyboard part and saying “what do you think of this?” So in a way, he was involved, putting his ideas in. But it was actually Darren and Vinny who wrote all the songs.’

For Cox, life was good. And the band was tight: despite their growing success, they remained good Northern boys at heart. One fan called Rob Till remembers missing his train after a gig, when the guys allowed him to sleep on the floor of their hotel. There were girls, too. Says Mick Taylor: ‘Obviously, there were groupies and that sort of thing.’ They indulged as you might expect, but Cox later insisted it was not so hardcore as some of their heavy metal contemporaries. ‘There were a few [groupies],’ he said, ‘although I was probably too naïve to notice at the time – I probably would have made more use if I had been older.’ He told Shortlist: ‘We were just a bunch of lads from Oldham who got a deal. If you’re 20 years old and you get plonked in the middle of LA with an expenses account, you’re going to have a drink, aren’t you? It was all quite innocent, really. I never crashed my Rolls-Royce into a swimming pool or anything – I had a rusty Ford Fiesta. And no pool to drive it into.’

With the advance they received, they paid themselves £75 a week and gradually increased this to £120. ‘We thought – “my God, we’ve made it!”’ They favoured Henry’s Wine Bar in Manchester and even impressed George Harrison. ‘After a gig one night we were sat in a bar and [Darren] saw this guy pushing in, so he told him to f*** off,’ Cox told Metro. ‘It was George Harrison. George said, “I haven’t been told to f*** off since 1965” and was so impressed, he bought us all a drink.’

Taylor, later the boss of their fan club, met the band around this time. ‘I was working at MFI in Rochdale,’ he remembers. ‘Me and my friend used to swap tapes with each other. One day he left a tape on my desk by Dare, who I’d never heard of. I listened to the tape and it was brilliant, so I asked him who they were. He said his wife’s cousin was called Darren Wharton and used to be in Thin Lizzy. I got that much into them that I started making a scrapbook. I went to see them live at a gig in Oldham. Unfortunately, they wouldn’t let me backstage, but I was with my friend and he was, so I left my scrapbook with him and asked if he could get the band to sign it. The next day at work, my friend said they were impressed with my scrapbook and next time I went to a gig, I should go and introduce myself. So that’s what I did. I went on tour with them and managed to get backstage passes all the time. In the end, Darren Wharton asked me if I’d run the fan club.’

Though Taylor tended to mix primarily with Wharton and Burns, he grew to know the rest of the band as well. ‘When I first met all of them, they were all quite young,’ he says. ‘Brian was the youngest in the band and the shy one, really. I wouldn’t expect in a million years that years later he’d be “Professor Brian Cox”. Back then no one knew that Brian was into science or what he was doing – he was just seen as a pop idol, if you know what I mean. He wasn’t the most talkative one. Obviously I did talk to Brian, but he was the quiet one in the band. I wouldn’t say it was hard to get him into a conversation, but he’d only answer questions that you asked him. It wasn’t that he was miserable – I think it was because I got myself more involved with Darren and Vinny and the other three members were in the background. It was a “hiya”, a shake of the hand and a nod of the head.’

A&M were keen to get the band playing more venues around the UK and abroad – especially on the continent, where rock music was particularly popular. In November 1988, they were sent out as a support act for Jimmy Page, ex-guitarist of Led Zeppelin for his UK dates. Neonbubble.com posted a humorous interview with Cox, in which he described his favourite hotel, talking about a place he stayed in while on tour with Page in Newcastle. ‘I can’t remember the name of the hotel but let me tell you this: mirrors on both sides of the bathroom!’ he said. ‘Luxury! You could look in one and see a reflection, and a reflection of a reflection and so on. In fact, I tried an experiment there by waving and seeing how long it would be before the distant reflections waved back – it was a test of the speed of light and how drunk I was – but some of the reflections didn’t wave at all and I got scared. That’s when I knew I’d never watch Poltergeist 3 again. And the towels were really fluffy – stole two.’

For the group, playing with Page was something of a dream come true, especially at the Manchester Apollo, the scene of many gigs they had watched as teenagers. They even got to see how realistic Spinal Tap was at a concert in Birmingham. ‘We did our set [at the Hummingbird],’ wrote Vinny Burns. ‘Jimmy came to our dressing room to say he enjoyed our show. He went out of the door and was about to walk down the steps to the stage (his intro was running). Darren shouted, “Have a good one, Jimmy!” and as he turned round to say thanks, he fell down the stairs. Oops! We were waiting to be booted off the tour but everything was fine.’

It’s hard to quantify just how successful Dare were in those early days but they had a solid live following. ‘If you went to a gig, the queues would be right round the block,’ says Mick Taylor. ‘I can’t understand why they weren’t huge. When we went to a Dare gig, it was brilliant. They’d get the crowd going and everyone was bouncing around – it was like a personal gig, in a way. It wasn’t like the stage was forty feet away and they were up twenty feet: they were there and you could actually touch the band.’ As well as their live reputation, Out of the Silence sold an impressive 50,000 copies in America (‘quite big, considering they were an unknown band,’ explains Taylor). And the critics liked them. Yet for some reason they didn’t quite break through.

‘I asked Darren why they didn’t go to the States to advertise their CD, but he said it was down to management,’ says Taylor. ‘They had poor management, really – that’s why they didn’t go to the States, or it might have been a different story today.’ The singles, too never really took off in the UK. ‘In England, the singles they released off the [first] CD did get in the low regions of the charts. It’s a shame, really but they were a good band and they had a great following.’ A second single, ‘The Raindance’, was released and got to No. 62 in the charts in April 1989. Distributed as a 7” gatefold vinyl, it featured five profile cards with trivia about the band members. Cox listed his pastimes as ‘squash, running and eating’. And despite being rock stars, he did retain some of his middle-class roots, playing squash with Wharton most mornings, since they only lived half a mile apart in Chadderton.

The band continued to work hard. ‘They did gig constantly,’ recalls Taylor. ‘I was surprised because when I first got into them, I’d go to one gig and think that’s it for another few months and then I’d be walking around Manchester and there would be an advert for another.’ While Brian and the guys were having fun, it never got too crazy. ‘We weren’t very rock and roll,’ Cox told the Sun. ‘The closest I got to mayhem was throwing a tea tray out of a window in a hotel room in Carlisle. We were only on the first floor and the teapot just bounced off the pavement next to a bemused passer-by. And we made sure to carefully open and close the window.’

The hotel was The Crown & Mitre in the city centre. So un-rock’n’roll was this particular episode that no one can remember it happening. ‘Roy, who worked here at the time, know who the band is,’ said a hotel spokesperson, ‘but doesn’t remember anyone doing that.’ A&M booked them a slot as the openers for Swedish rockers Europe, then riding high in the charts with the follow-up to their mega-selling album, The Final Countdown. The 58-date Out of this World tour saw Dare tour across the continent, playing to packed stadiums of more than 12,000 people in places like Paris and Stockholm. ‘This was one of the best times I have had on the road,’ wrote Vinny Burns. ‘The guys from Europe and all their crew were amazing. In over four months, there were no arguments between bands and the general vibe was a four-month party.’

The tour helped to improve Dare as a live outfit as they got used to the bigger venues. Wharton stopped using the Batmobile and being able to run around the stage meant their stage presence became even better. Shelly hooked up with Europe’s wardrobe lady, while Cox got his second taste of televisual fame when one of the concerts was broadcast on RTL in Germany. At the last gig, Dare ran up onstage to cover the headliners in cream as a practical joke. And while no one following the band knew particularly of Cox’s scientific inclination, it was clear that despite his musically enforced hiatus, it was never a subject far from his mind. ‘I remember Brian Cox with his big smile and an inquisitive mind trying to figure out the science behind the famous “Final Countdown” keyboard sound,’ says Europe frontman and founder Joey Tempest. ‘A very humble and warm individual.’

The tour reached Britain in late March 1989, with dates at the Birmingham NEC and London Hammersmith Odeon. A&M released another single, “Nothing Is Stronger Than Love”, which didn’t chart. But the band were getting itchy feet about recording new material: while on tour, they had been writing new songs and were keen to put them on tape. There was also something of a split within the group. Bass player Shelly and drummer Jim Ross appeared to have fallen out of favour with the rest of the band and ended up being replaced. In an interview with Hot Metal, Cox revealed: ‘By the time the final split came, Darren, Vinny and I had recorded about seven new songs, playing all the instruments between us.’ Nigel Clutterbuck was brought in on bass, while Greg Morgan took over the drummer’s slot.

Searching for a more layered sound, especially onstage, a young graduate from the Salford College of Music called Richard Dews was also hired as an extra guitarist. Cox survived the cull. ‘He was very popular with Darren,’ says Mick Taylor. ‘In Darren’s eyes it was Darren, Vinny and Brian – they were good friends.’ Certainly, Cox was now considered one of the senior members of the band despite still being only just into his twenties. And he was keen to affirm that the new line-up only made Dare stronger. ‘The whole band is so tight now, too,’ he said. ‘When we rehearse, we hardly need to do much of the old stuff because it’s all there. We tend to concentrate more on developing new material, which we are hoping to do in the new set.’ The band had been hinting at a different, heavier sound during their gigs, showcasing the new song ‘Breakout’. They were also playing some Thin Lizzy covers. ‘The crowd seemed to like it,’ he said. ‘I think it’s just good fun. We’re certainly now trading off the memory of Lizzy and considering Darren was in the band, we’ve got every right to perform a couple of their numbers.’

‘Darren thought the crowd wanted them to go heavier,’ says Taylor. ‘Out of the Silence was more melodic rock, but Blood From Stone was heavy.’ Blood From Stone was the group’s sophomore effort and on top of a harder sound, also had elements of a Celtic influence, which would feed into the group’s later records. It was recorded in Los Angeles with famed producer Keith Olsen, the man behind smash hits such as Whitesnake’s ‘Here I Go Again’ and Rick Springfield’s ‘Jessie’s Girl’ and released in September 1991. A&M said: ‘On a far heavier and unequivocally more representative album, [Dare] dispel for good the ill-fitting AOR title from their collective shoulders. The British have a fine musical tradition and when that tradition is enhanced by a passionate emerald hue, then you know that not only are you in for a consummate musical treat, but also that one of the very finest exponents is Dare.’

The critics were generally positive. It received four stars in Kerrang!, which wrote: ‘Darren Wharton and guitarist Vinny Burns have retained only keyboards man Brian Cox (who doesn’t have an awful lot to do anymore!).’ The first single was ‘We Don’t Need A Reason’, which was released a month earlier in August 1991 and reached No. 52. It was their highest-charting single. During an interview, one journalist compared Blood From Stone to the work of metal group Skid Row, much to the consternation of the band. ‘It doesn’t sound like Skid Row,’ opined Wharton, with Cox adding: ‘it doesn’t say “fook” on it 18 times either!’

Meanwhile, they were still incredibly popular around their hometown. Fans flocked to the Golden Disc in Hilton Arcade to have albums, posters, jackets and more signed by the band and to catch a glimpse of the new line-up when the single ‘Real Love’ was released in October 1991. It spent one week in the chart at No. 67. Cox talked of a return to the Queen Elizabeth Hall in Oldham for a homecoming concert, which would far outstrip their previous performances there. They even tried to emulate the likes of Def Leppard, who had created alter egos for themselves, forcing one game journalist to call Cox ‘Corky’ throughout an interview.

Despite their protestations, it became clear that the end was nigh, though. ‘A&M had done as much as they could and nothing was happening,’ explains Mick Taylor. ‘Then the manager left.’ In retrospect, Wharton realised Blood From Stone’s new sound hadn’t really worked. ‘I hate to say it but we were all sheep back then,’ he said subsequently. ‘Looking back, it was definitely the wrong thing to do. We should have had the maturity not to jump on the bandwagon. As far as Dare are concerned, Blood From Stone was too much of a change in direction and we suffered for it in the end, really.’

The constant touring was beginning to take its toll, too. One time, a roadie called Drac led a team which ended up with Cox gaffer-taped to a lighting rig for over an hour. ‘I was probably not behaving in a way deemed appropriate for a member of a band in the presence of road crew,’ said Cox. ‘I think I was just being a general, you know, pain. [Drac] was the tour manager, so he ordered the rest of the crew to put me on the ground, gaffer me up into a ball, put a harness on and then attach me to a lighting rig at the Hammersmith Odeon.’ Asked whether he could remember what drove them to it, Cox replied: ‘It was a build-up of absolute annoyance over many weeks.’ The final tipping point came in Berlin. ‘It was a proper fight,’ said Cox. ‘We were drunk and tired, and everyone just jumped on one another.’ He elaborated to Shortlist: ‘We’d been touring for four years and we were sick of each other. We all threw a few punches in a half-hearted way. Nobody’s nose got broken; it was slapping, mainly – like those fights that footballers have. But it was enough to split up the band.’

A&M were on the verge of dropping Dare anyway because Blood From Stone was a massive change and it didn’t do well at all.’ Indeed, the album spent one week in the charts and got to No. 48. Wharton has suggested that A&M were bought by Polygram and that’s why they were left out in the cold (in a strange echoing of his solo deal with Phonogram), but it didn’t really matter: the record company dropped them and it was decision-making time. News of Burns’ exit hit the music papers but was relayed to the heartbroken fans, along with a sad editorial about the split from A&M, in Dare’s official fanzine #8. The edition also added: ‘Brien (sic) is also leaving Dare! The reason for Brien (sic) leaving is that he is going to university some time this year, so we all wish Brian the best of luck, cheers mate.’

At first, despite Vinny leaving, it appeared that Cox would stick with Dare because Wharton suggested in an interview that he would continue working with the other members of the band. However, it’s clear that once A&M got wind of the lead guitarist’s departure and decided to terminate their contract, Cox decided it was time to get back to his academic pathway: ‘I just decided that I would carry on doing physics,’ he explained.

Dare did continue on. Not long after Cox left, they played Manchester Rockworld and he came to see them play. ‘They’re still going now,’ says Taylor. ‘Dare is really Darren Wharton and there have been various line-up changes, but Brian was there for the first two CDs.’ Vinny Burns went on to join Asia and Ultravox and then became big in Japan as a member of Ten. The Maple Squash Club was torn down years ago and flats built in its place. NL Distribution re-released Out of the Silence in 2008, probably to capitalise on Cox’s newfound fame. ‘I’ve got four albums on my phone and I regularly listen to them,’ says fan Tony Steel.

Taylor lost contact with Cox after he quit Dare. However, a random trip out with Darren Wharton after the band had split led to a mini reunion. ‘I did actually see Brian in the pub once,’ says Taylor. ‘Brian was asking Darren how he did his different tones of voice – you know, when you harmonise in a studio? He wanted to know about octaves and things like that and how to do them. So he was obviously doing a bit of singing with D:Ream or something in the studio with them. That’s the only time I’ve seen Brian after he left Dare.’

Cox’s hair metal days were over. Despite being his entrance into the music business and a fundamental era in moving from young adult to grown-up, Dare are only ever mentioned as an afterthought in interviews with the scientist. Instead, he’s known as the rock star physicist who played keyboards with D:Ream – ironic considering his position in Dare was far more substantive than in the late-Nineties dance act, as we’ll explore. In fact, when asked about his time in pop, Cox himself set the record straight. ‘My memory of music is not D:Ream,’ he said. ‘It’s more this band Dare I was in.’ The Maple Squash Club regulars will be glad to hear him say that. Despite leaving the band the long hair remained (and would so for a number of years), but it was time to head back to academia.