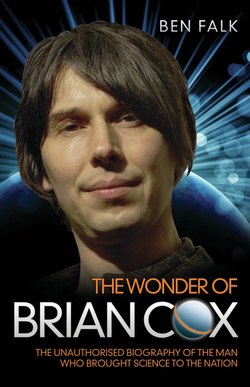

Читать книгу The Wonder Of Brian Cox - The Unauthorised Biography Of The Man Who Brought Science To The Nation - Ben Falk - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеThere’s not an arm-patch in sight. Instead, a young-looking man with a mop of black hair settles comfortably in a chair on the stage of the Royal Festival Hall in London, bespectacled colleague to his left. He’s wearing a grey T-shirt, black jacket and trainers – the trousers, of course, black. The whoops die down. That’s right, there was whooping when these two men in their early forties walked casually onto the stage in front of 2,500 paying spectators, who had come to hear them talk about quantum physics. It’s an eclectic crowd – young, old, male, female – not the fusty audience you might expect for what amounts to a discussion about two-slit theory and how it’s possible for a particle to skip to any part of the universe in a heartbeat. Personally, I struggle to understand what they’re talking about, but then I gladly gave up science at GCSE. It’s not that I don’t appreciate the subject, it’s simply my brain is not equipped to deal with these kinds of concepts.

Professor Brian Cox, for it is he beneath the floppy black fringe (though thin strips of grey are beginning to poke through), believes anyone can understand the basics of quantum mechanics with a bit of application and over the next 45 minutes, he and his colleague, Professor Jeff Forshaw, try to do just that. It probably works for some people; it doesn’t for me. But whether they understand it or not, the packed house is on the edge of their seats. When Cox opens up the floor to Q&A after their lecture, hands shoot up so quickly and strenuously they are practically wrenched out of their sockets. For the most part, he answers the questions patiently, stopping to rant about how angry he gets when scientists are equated to an interest group, to make fun of the way he sometimes speaks on television and occasionally gives short shrift to someone, like the man who earnestly enquires about a true vacuum and whether it’s possible to create one. The answer, says Cox, is no. Though one person does request tips on seeing the Northern Lights, no one asks if they can marry him, or have his babies, or have him sign their breasts – at least not out loud. But as he stands in his familiar way, legs fairly wide apart as he clarifies a point on a large teacher’s notepad, it’s clear that Professor Brian Cox is without doubt the most famous and celebrated scientist in Great Britain right now and possibly of the last 10 years.

The funny thing is, it’s not because of something he’s discovered, or because of the Nobel Prize he won. Instead, Cox – labelled jokily by his friends as the ‘Peter Andre of particle physics’ – has become as famous as he is because of his ability to communicate science. His 2010 BBC series Wonders of the Solar System averaged a staggering 5 million viewers a week, while the 2011 follow-up, Wonders of the Universe, did even better, with an audience of 6 million viewers a week. Because of this, he’s mentioned in the same breath as Sir Patrick Moore, or Sir David Attenborough – science presenters who have captured the zeitgeist. A particle physicist by trade, Cox is also a professor at Manchester University, where he completed his doctorate, as well as a Royal Society University Research Fellow. He has worked on the H1 project at HERA accelerator in Hamburg, a predecessor to his current official job as a researcher on the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Geneva, Switzerland. And he has also published a number of successful academic papers in addition to four books. In other words, he really knows his stuff.

Yet there’s another reason why Cox is so comfortable on stage at the Royal Festival Hall. His past life includes stints in the chart-topping band D:Ream, as well as the rock band Dare, playing keyboards on tours around the world and on BBC’s Top of the Pops. David Attenborough can’t say he was in the band at the Labour Party election victory bash of 1997. Nor can Patrick Moore lay claim to being one of People magazine’s Sexiest Men Alive, a poll in which Cox was included in 2009. Furthermore, he’s universally considered a nice guy. If you’re looking for tales of drug abuse, broken hearts and plates thrown at assistants, you won’t find them here. Try as I might – and for the sake of balance I did try – I couldn’t find anyone who questioned his integrity or personality, though some took issue with his screen presence, while others showed disgruntlement at his ubiquity.

All this and more will be examined here, including several exclusive interviews with those who knew Cox as a student at Oldham Hulme Grammar School, a post-graduate student in Germany, a big-haired rocker behind the keys onstage at Maple Squash Club in Oldham and beyond. Although he hasn’t participated in this book, there are exclusive, never-before-seen quotes from the man himself. I interviewed him just before he became really famous in February 2010 when he was starting to promote Wonders of the Solar System. According to my emails, he was very difficult to pin down, his insanely busy schedule and desire to do it all already proving tricky to manage. I finally managed to contact him at his house in Battersea, where via an occasionally poor phone line (not sure why when it was just across the river in London, shouldn’t he be able to fix it?), he talked with passion about his programmes and future plans.

Though I knew little about him, I was already intrigued as to how someone who has been hired as a professional scientist rather than a professional presenter finds time to ensure he maintains his academic credentials and whether he senses resentment from within his own community. ‘I’m fairly sure it’s accepted now that someone needs to [do these sorts of programmes],’ he told me. ‘We’re always having funding crises one way or another and we’re always fighting for public and governmental support. It’s changed over the last 10 years and it’s widely accepted that some people have to do it. As long as you have a small number, it works.’ Still, he continued: ‘I think the reason you’re valued on TV or writing articles is because you’re a scientist and have a particular way of looking at the world, or an attitude that comes from being a research scientist. I think if you lose it, you become less good at presenting it.’

More than two years on and a whole load of fame later, it’s interesting to wonder whether he sticks by that edict. One former boss revealed to me that following the first series of Wonders… he bumped into Cox at a party, where the Professor told him that he was returning to science. Other fellow scientists suggest maybe his greatest achievement will be his ability as a communicator. There’s no doubt Cox has used his fame, such as it is, for the good, whether visiting schools and encouraging pupils to pursue physics, or arguing with relevant government ministers for better funding for science. Indeed the so-called ‘Brian Cox Effect’ which will be examined in more detail later has been bandied about by the media, who argue more kids have taken up science as a result of his documentaries.

Cox’s great hero, the American writer and scientist Carl Sagan, wrote in his book Cosmos of his belief of man’s inherent desire to understand the building blocks of our world, our connection to the universe and how this would best be communicated through the language of television. Sagan’s similarly-titled TV series was three years in the making and its estimated audience was ultimately 140 million. In his 1980 text to accompany the landmark show, he wrote: ‘Whatever road we take, our fate is indissolubly bound up with science. It is a matter of simple survival for us to understand science.’ As Cox himself told me: ‘Someone’s got to do the actual science or you’d have nothing to talk about.’ But as CERN continues to learn more and more about the fabric of our universe and neutrinos fly around the world at speeds we cannot possibly fathom, perhaps it’s down to Professor Brian Cox to tell us all about it. And if he happens to have been part of a band who had a No. 1 hit, then hey, why not?

One thing should be pointed out here. Obviously, the publishing industry cannot predict the speed of scientific progress. As such, all science facts contained herein are correct up to the end of January 2012. If aliens show up or someone decides to go back to the future after that, please forgive me for not mentioning it within these pages.