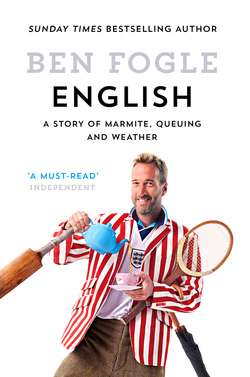

Читать книгу English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather - Ben Fogle, Ben Fogle - Страница 5

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеThere was a hubbub of excited chatter as, clutching steaming cups of tea, the women gathered around a series of small tables to admire the spoils of war. The Great Yorkshire Show had just finished and the crochet, patchwork, flower arranging and cakes had all ‘come home’. There was a general chatter of approval. The room was decorated with bunting and it had the air of a village fete. This was Jam and Jerusalem.

I was in Harrogate, North Yorkshire, for the weekly gathering of the Spa Sweethearts Women’s Institute. The WI, as it is known, was formed in 1915 to revitalize communities and encourage women to produce food in the absence of their menfolk during the First World War. Since then it has grown to become the largest voluntary women’s organization in the UK, with more than six thousand groups and nearly a quarter of a million members.

The Queen herself is a member, and the WI, in my humble opinion, understands better than any other organization how the country works. Always polite, it has a reputation for no-nonsense, straight talking. The chairwoman of the WI’s public affairs committee, Marylyn Haines-Evans, recently said, ‘If the WI were a political party, we would be the party for common sense.’ If anyone understands the quixotic essence of Englishness, it is the ladies who attend these regional WI gatherings.

I chose the location carefully too. Popular with the English elite during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, during the Second World War, government offices were relocated from London to the North Yorkshire town and it was designated the stand-in capital should London fall during the war. It frequently wins the Britain in Bloom competition and has been voted one of the best places to live in the UK. It is what I would call a solid Yorkshire town. The combination of Harrogate and the WI is, I think, the perfect English ‘brew’.

I had come along to one of the WI’s evening gatherings to find out what Englishness means to them. Rather uncharacteristically, I was a little nervous as I walked to the stage in the small hall. I had brought my labrador, Storm along as an icebreaker and for some moral support, and together we made our way to the centre of the stage.

It was a relatively small gathering, perhaps fifty strong, but these women have solid values and in my mind they are the voice of England. Ignoring the jingoistic reverence that a national sporting event or royal occasion generates, I asked them what Englishness means.

‘The weather.’

‘Queuing.’ A lot of nodding heads.

‘Apologizing. We are always apologizing,’ stated another woman to a chorus of agreement.

‘Roses and gardens.’

‘Tea.’ This got the loudest endorsement.

‘Baking and cakes.’

‘The Queen.’

I asked them whether they would ever fly the St George’s Cross from their homes. There was an audible gasp, accompanied by a collective shaking of heads.

‘Why not?’ I wondered.

‘Because it has been hijacked by the extreme right,’ answered one woman.

‘It represents racism and xenophobia,’ added another.

‘We aren’t allowed to be English, we are British.’

I asked whether we should celebrate our national identity more like the Welsh, Scots and Northern Irish. To which the whole room nodded in approval, not in a jingoistic, nationalist kind of way, but in an understated, English kind of way. It was a genteel, considered discussion of the virtues of Englishness and the erosion of our national patriotism.

‘The Last Night of the Proms is as patriotic as we get,’ explained another member of the group, ‘but that patriotism is about the Union.’

Here England was speaking. We have a solid idea of what it is to be English, we have a grasp of some of the character traits of living Englishly, but we no longer celebrate that Englishness.

I asked if it was time to reclaim our national identity and take pride in being English. There was a round of applause.

‘Reclaim the celebration of Englishness for us, Ben.’

And that is what this book is about.