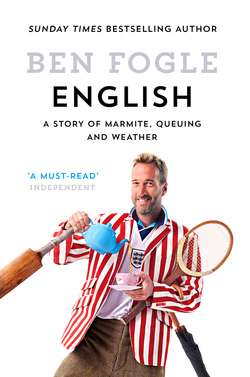

Читать книгу English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather - Ben Fogle, Ben Fogle - Страница 8

WHATEVER THE WEATHER

Оглавление‘Sunshine is delicious, rain is refreshing, wind braces us up, snow is exhilarating; there is really no such thing as bad weather, only different kinds of good weather.’

John Ruskin

Millbank Studios, opposite the Houses of Parliament, was a hive of political activity as I made my way into the entrance hall.

‘Hello Ben,’ smiled a smart-looking man in full naval ceremonial dress.

‘Hello sir.’

It was Lord West of Spithead, former First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff. During my Royal Naval Reserve days, he was kind of a big deal. He also happens to be the father of my great friend, Will.

‘What are you doing here?’ he enquired. ‘About to climb Everest?’

‘I’m here to be a weather presenter.’ At which point I think I lost his attention and he marched off towards Parliament with a wink.

I was ushered down a narrow corridor, through a high-security door and into a large TV studio, ITV Weather’s dedicated meteorological nerve centre. I had decided that any quest in search of Englishness had to start with a visit to the place we go for our daily weather fix.

‘Hello Ben,’ smiled Lucy Verasamy. ‘Cup of tea?’ she asked (obeying rule one of Englishness).

There was no need for weather small talk here. Lucy is weather. She lives the weather and she loves the weather. ‘What percentage of your life do you spend talking about the weather?’ I asked.

‘About fifty per cent,’ she smiled.

When it comes to dinner-party conversation, Lucy’s job must make her the best guest. All her weather small talk is big talk. She knows everything about it. She positively oozes weather fanaticism, speaking at 100mph. I thought I was good at talking until I met Lucy.

‘Do you want to see the studio?’

I felt like a child in a sweet shop. I’m sure I’m not supposed to be this thrilled by a weather studio, but apparently I’m not alone. ‘People do get pretty excited,’ she admitted as we walked into a large empty room with a huge green piece of fabric hanging from the wall. ‘Same one Harry Potter’s cloak was made from,’ she winked.

She walked onto her presenting mark and immediately an image of her standing in front of a large map of the British Isles appeared on one of the monitors. This is the picture of the professional weather presenter we’re used to seeing.

Given that we can now access the weather from multiple sources, I wondered what the role of a weather presenter is in 2017.

‘You can get weather apps, weather online, weather in social media, in the papers, on the radio,’ she explained, ‘but the weather presenter’s role is to interpret that data and translate it for our viewers.’ A digital weather report can’t predict humidity, hay fever risk and all the other important effects of the conditions on our lives.

‘What’s the most common question?’

‘“Is it going to snow at Christmas?” followed by “Will it be a hot summer?”’

You can’t say we aren’t predictable.

Of course, all weather presenters are now marked by the most notorious weather-presenting ‘moment’ on 15 October 1987, when Michael Fish got the forecast wrong in spectacular style. ‘Earlier today a woman rang the BBC and said she’d heard there was a hurricane on the way. Don’t worry. There isn’t,’ he announced cheerily during the weather slot on the One O’Clock News that day. That night, force 11 winds gusted across the south of England for several hours, uprooting 15 million trees and causing total mayhem. Fish’s legendary ‘blooper forecast’ has since had more than half a million hits on YouTube.

In a typically English way, Fish has lived up to the ‘gaffe’ – though he maintains he was talking about a different storm system over the North Atlantic which didn’t reach England, not the depression from the Bay of Biscay that caused the damage. He makes regular appearances on comedy shows, reliving the ‘hurricane blooper’ with self-deprecating humour. Thanks to the bankability of weather as a topic of interest to the English, the controversy has spun its own cultural sideshow. The term ‘the Michael effect’ was coined for the tendency ever since of weather presenters to predict a worst-case scenario in order to avoid being caught out. Fish appeared as guest presenter of the weather news on the twentieth anniversary of the Great Storm. A clip of his original bulletin was immortalized and given global exposure as part of a video montage in the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Summer Olympics.

Back in the 1980s and early 90s, weathermen really were a big deal. Ulrika Jonsson began her career as a ‘weather girl’, becoming the nation’s sweetheart. Michael Fish’s weather rival was John Kettley, and together they were immortalized in a 1988 novelty hit by A Tribe of Toffs from Sunderland, ‘John Kettley is a Weatherman’:

John Kettley is a weatherman

a weatherman

a weatherman

John Kettley is a weatherman

And so is Michael Fish

‘People still talk about Michael Fish,’ Lucy marvels, ‘even people who weren’t born till after the storm.’ It’s one of my first observations about our obsession with the weather that weather forecasters can become national treasures. Lucy trained under the eye of another great weatherman, Francis Wilson. Amongst Francis’ many accolades is he was the first to use computer-generated graphics on British television.

‘Have a go on the weather map,’ Lucy says. ‘Use the map, but engage with the audience,’ she explains as I stand in front of the invisible map ‘hidden’ in the green screen. I glance at the monitor and there, in full Technicolor glory, is my face and arms, gesticulating to the map.

‘We are one of the few live TV broadcasts not to use autocue,’ she says with pride.

Behind me on the television monitor is a map of Britain with moving weather arrows to show the direction of wind, and large green patches to show the rain and showers. More easily identifiable are the yellow and orange circles showing the temperature – the deeper the orange, the hotter the forecast temperature.

‘It will begin cool in the south before getting warmer.’ My attempt at presenting makes me feel slightly fraudulent. And then I remember that ITV Weather alone has 15 million viewers a week and realize the responsibility of the job.

The problem with Britain is that most of the big weather is in the north, while the majority of the dense populations are in the south. The result for a weather presenter can be arms waving wildly high and low on the map, like some Karate Kid impersonation. ‘Francis always told me not to look like I was dancing or chopping with my arms,’ Lucy explains.

‘People love to grumble about the weather,’ she smiles, ‘too hot, too cold, too windy. I suppose it plays up to our national stereotype of a nation of grumblers.’ Interestingly, she attributes the vast number of weather apps now available to our eternal search for ‘the right weather’: if people don’t like a weather prediction, they will look for one that suits them. Trying to tame the untameable weather.

Lucy explains that there are several features that make the English weather what it is, changeable and famously unpredictable. As part of the United Kingdom, England lies between latitudes 50 and 56 degrees north. An island country, it sits on the western seaboard of the continent of Europe, surrounded by sea. The English live at a point where competing air masses meet, creating atmospheric instability and unsettled weather. In The Teatime Islands, my first book, I described England/Britain from the perspective of a faraway outpost as ‘this small rainy island in Western Europe’.

On the other side of the country, our geographical position on the edge of the Atlantic places us at the end of a storm track, a relatively narrow area of ocean down which storms travel, driven by the prevailing winds. As the warm and cold air fly towards and over each other, the earth’s rotation creates cyclones and the UK bears the tail end of them.

What makes our climate so mild is the Gulf Stream, which raises the temperature in the UK by up to 5°C in winter. It also adds moisture to the atmosphere, which makes it much harder to predict the weather as it adds to the number of variables that need to be forecast.

These variables mean vastly unpredictable weather. I can remember both snow at Easter and also such heat that the chocolate eggs were melting. November can be hotter than June, and winter often doesn’t arrive until February. We are more likely to have snow at Easter than Christmas. We can wear T-shirts in November. It’s all topsy-turvy, and that is what we love to talk about. Even within England, some regions are more susceptible than others to certain kinds of weather as the air masses jostle for dominance. North-west England is buffeted by the maritime polar air mass, which can bring frequent showers at any time of the year. North-east England is more exposed to the continental polar air mass, which brings cold dry air. The south and south-east are closest to the continental tropical air mass, which carries warm dry air. The south-west is the area most exposed to the maritime tropical air mass, which ushers in warm moist air. Wet, dry, warm, cold, it is a proper maelstrom. ‘There’s a lot of weather about today,’ meteorological sages like to say mysteriously, as if the skies are full of gods of the elements whimsically calling the shots with thunderbolts and winds, lightning and storms. No wonder so many folk sayings ‘reading the weather’ remain popular. ‘Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight. Red sky in the morning, shepherd’s warning’ first appears in the Bible in the Gospel of Matthew but has led to variations such as ‘Red sky at night, sailor’s delight. Red sky in the morning, sailor’s warning’. ‘Rain before seven, fine by eleven’ is another which emphasizes the variability of the weather systems passing over our green and pleasant land.

Lucy has presented hundreds if not thousands of weather reports over a decade. ‘The thing about being a weather girl is that the weather always leads,’ she smiles. ‘We are merely the messengers, we can’t change the weather.’

While it’s fair to say I will probably never become a weatherman, at least Lucy has a warm studio in which she can shelter from the worst of the elements, which is a lot more than can be said for what is arguably England’s most extreme forecasting job, that of the Fell Top Assessor. This was the next port of call in my English weather odyssey.

A bitter wind ripped across the car park as I made my way to the waiting Land Rover. It was midwinter and I was joining a man with one of the most unusual weather jobs in England.

I have always loved the Lake District. I will never forget the first time we went there as a family. I couldn’t believe that England had such a magical, watery landscape. I still get that childhood excitement whenever I visit as I hurtle back to my childhood. It is the location of Swallows and Amazons.

But today I was in the Helvellyn range of mountains, between Thirlmere and Ullswater, ready to climb Helvellyn itself. It is a dramatic, rugged mountain – at 3,117ft the third-highest point in England – and from its summit, on a clear day, you can see Scotland and Wales. Alfred Wainwright, the celebrated fell walker and guide book author, described one ridge to Helvellyn Plateau as ‘all bare rock, a succession of jagged fangs ending in a black tower’, which makes the fact that there have been a number of fatalities on the mountain over the years understandable.

The rocks of Helvellyn were forged in the heat of an ancient volcano some 450 million years ago. It inspires poetry as well as respect for its dangers. Coleridge and Wordsworth both wrote about it. This is the final stanza of Wordsworth’s poem ‘To ——, on Her First Ascent to the Summit of Helvellyn’:

For the power of hills is on thee,

As was witnessed through thine eye

Then, when old Helvellyn won thee

To confess their majesty!

The mountain has attracted lots of odd adventurers. In 1926, one man landed and took off from the summit in a small plane. Today, though, Helvellyn is arguably best known for one of the strangest weather-forecasting jobs in the world: that of the Fell Top Assessor, whose role is to assess both meteorological and ground conditions to provide an accurate local forecast for the estimated 15 million visitors to the Lake District National Park each year. The key is to check the ground underfoot and predict avalanche risks.

Dressed in multiple layers against the bitter wind, soon we were in the cloud as the temperature plummeted and the trail became increasingly icy. Thick grey cloud clung to the Cumbrian valleys. Drystone walls disappeared into the gloom as we began our hike. We were forced to strap crampons to our boots as we ascended the snow and ice. Gripping my ice axe in one hand, we beat into the wind that had dropped the temperature to a freezing minus 9°C. Ice formed on my eyelashes as we continued past half a dozen hardy mountaineers.

Soon we had reached the summit, where the Fell Top Assessor’s real work begins. He pulled his tiny notebook from his jacket and assessed the conditions. Tiny horizontal icicles, known as hard rime, had formed on every surface, including us. These miniature formations of spiky ice grow into the wind, giving an indication of the prevailing winds on the summit. Wind speed and wind chill measured, within minutes he had gathered the necessary data, and after a quick mug of tepid tea from a Thermos flask, we began our descent.

Every day, come rain or shine, wind or snow, storm or hurricane, the Fell Top Assessor climbs the peak to report on weather conditions from the summit. That’s every day. Working seven days on and seven days off, the two assessors will take it in turns to make the daily climb, often braving temperatures as low as minus 16°C. It is estimated that the fell top assessors climb the equivalent of Everest every two weeks.

Unsurprisingly, candidates must have ‘considerable winter mountaineering experience and skills, preferably with a mountaineering qualification’, according to the job description, which continues, ‘You will provide information and advice to other fell users to ensure safe and responsible use of the mountain. You will also identify and carry out basic rights of way maintenance on the routes.’ Other skills required include the ability to write concise reports, assess snow and ice conditions and use a map and compass.

Jon Bennet, who has been a fell top assessor on Helvellyn for eight years, says: ‘Fell top assessing is the best job, and to be out in the hills doing something as worthwhile as this is a perfect combination.’ The job is not without its perils, however, as several walkers have lost their lives on the peak in recent years.

In October 2016 Robert Pascoe, a 24-year-old RAF engineer, was killed when he lost his footing while walking with a companion on the Striding Edge side of Helvellyn and fell 650ft down the mountain. In 2010, Alan Burns, thirty-nine, from Preston, Lancashire, suffered fatal head injuries in a fall from Swirral Edge. Three days later, Philip Ashton, forty-three, from St Helens, Merseyside, fell from the same ridge while walking with friends and died later in hospital.

Yet Helvellyn is one of the most popular fells with walkers in winter and summer, attracting ramblers and experienced mountaineers who come to enjoy the views and the diverse topography. And the Striding Edge route to the summit is one of the busiest.

And as far as jobs go, being the Fell Top Assessor probably beats sitting in front of a computer screen for eight hours a day. At least, that’s what the adventurer in me thinks. More generally, the job tells me that English people are prepared to go to any extreme to provide others with the most precise information about the weather.

‘What’s the weather like?’ asked my mother as I clung to the side of a tiny rowing boat in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. I was on a satellite phone, 1,500 miles from land, and my mother was asking about the weather.

‘Warm, a little rain, beautiful cloud formations,’ I answered. ‘What about you? Is it cold?’

‘Freezing, I had to scrape a thick layer of ice off the car.’

‘We’re expecting rain later.’ I replied.

I was six weeks into a gruelling and frankly rather dangerous bid to row across the Atlantic Ocean, and my rare link to the outside world via satellite phone was dominated by chats about the weather. How English is that?

We love to talk about the weather. It’s all about the weather. I have lost count of the number of conversations I have had around the world that have been about weather. And now here I was on one of my most dangerous trips, and my mother’s main concern was the prevailing weather conditions.

The first time I met the Queen (apologies for the humble brag there – very unEnglish, maybe it’s the Canadian part of me coming out), it was at Windsor Castle. It was December and I was, quite honestly, a little nervous. She had gathered the great and the good from the world of rural and agricultural life to celebrate the countryside.

‘What am I going to talk to her about?’ I worried as I made my way to Windsor. There were so many things I could tell her, about the places I had been and the adventures I had experienced. I would tell her about Antarctica, and of the time I met a tribe in the jungles of Papua New Guinea. Perhaps I would recall meeting the Prince Philip Island cult, or the time I met some of her Labradors.

‘It’s terribly cold, Ma’am, isn’t it?’ I smiled as I shook her gloved hand.

‘Warmer than last December. Though we could do with a little rain,’ she replied.

We both nodded, and she headed off to chat to the next guest.

And that just about sums it up. My first opportunity to chat to Her Majesty, and I talked about the weather.

I have found myself in the most unlikely situations around the world discussing the nuances of the English weather. And here’s the thing: we don’t really have weather. As Lucy Verasamy told me, it can be a little rainy, a little windy, sometimes a bit sunny – but let’s be honest, the strangest thing about the English weather is that it’s all a little meh. Compared to other countries it really is quite benign.

If you doubt me here, just take a trip to the Andes, or Borneo or even the US, and you will see what I mean by BIG weather. I’m talking about hurricanes, tornadoes, freezes, heatwaves. In England we have variables, but most of our weather-related conversations revolve around too much rain, or too little rain, or it being too warm, or too cold. And that is about it. It amazes me that we are capable of talking about the weather so fluidly and constantly when it varies so little.

Visitors from abroad are thoroughly bemused by the English fixation with the weather – because the only extreme aspect of our weather is its changeability. The conditions our climate might usher in from one day to the next induce inordinate anxiety, even though we technically ‘enjoy’ a temperate climate, with temperatures rarely falling lower than 0°C in winter or rising higher than 32°C in summer. English weather plays out its repertoire of conditions right in the middle of the range of potential hazards – certainly without the blizzards, tornadoes, hurricanes, killer heatwaves and monsoons that plague other geographical zones. We don’t have to batten down storm hatches, switch to snow tyres or build homes to strict storm mitigation codes (as they do in New England). We don’t have companies offering storm-chasing adventure holidays. It is said that, on average, an English citizen will experience three major weather events in their lifetime. The singular characteristic of the English weather is that it changes frequently and unexpectedly.

And this leads on to another point about our relationship with our weather: our propensity to complain about it. This is at odds with the Blitz-like spirit of ‘mustn’t grumble’, but we do. I think we have a tendency to be a pessimistic nation, particularly when it comes to the weather. Is there such a thing as ideal weather for the English? Isn’t it always too hot or too cold, a bit grey or intolerably windy, unbearably humid or relentlessly drizzly? It’s rarely right.

How many times have you heard someone saying the weather is perfect? Even on those rare cloudless, windless summer days of unbroken blue sky, there is often some reason to lament the weather: ‘It’s too hot’, ‘The grass is turning brown’, ‘We need rain’, ‘Careful or you’ll get sunburn’. You get the point.

But somehow the weather is part of our psyche. It may have something to do with our geographical location in the North Atlantic and the resulting propensity for it to rain.

Here are some English weather stats. The hottest recorded temperature was 38.5°C (101.3°F) in Faversham in Kent on 10 August 2003. The hottest month in England is August, which is usually 2°C hotter than July and 3°C hotter than September. The sunniest month was over 100 years ago, when 383.9 hours (the equivalent of thirty-two 12-hour days) of sunshine were recorded in Eastbourne, Sussex in July 1911. The lowest August temperature was minus 2°C on 28 August 1977 in Moor House, Cumbria. Highest rainfall in 24 hours was 10.98in (279mm) on 18 July 1955 in Martinstown, Dorset. The largest amount of rain in just one hour was 3.62in (92mm) in Maidenhead in Berkshire on 12 July 1901. The lowest temperature recorded in England was minus 26.1°C at Newport in Shropshire on 10 January 1982.

Wherever I am in the world, I am asked about the weather at home. I never know whether this is genuine curiosity about the renowned unpredictability of English weather or a reliable conversational gambit – an ice breaker, so to speak – because it is assumed that anyone hailing from England is totally fixated on the weather. As Professor Higgins told Eliza Doolittle when he launched her into society in the film My Fair Lady, it is advisable when making conversation to ‘stick to the weather and everybody’s health’.

It’s true that the English always hope for a White Christmas or a Summer Scorcher, and worry about a Bank Holiday Wash-Out or a Big Freeze. Weather warrants capital letters. It has status in everyday life. But the obsession is not just with the big picture; it is about the minutiae of each day’s conditions. There is no doubt that the English are genetically tuned to be on tenterhooks as to (a) what the weather is looking like each morning and (b) whether conditions are exactly as have been forecast.

We secretly like the fact that our weather continually takes us by surprise, often several times in the course of one day. The changeability of the weather has been a source of marvel, anxiety and unfailing interest since the year dot. In 1758 Samuel Johnson wrote an entire essay entitled ‘Discourses on the Weather’. ‘It is commonly observed,’ he pointed out, ‘that when two Englishmen meet, their first talk is of the weather; they are in haste to tell each other, what each must already know, that it is hot or cold, bright or cloudy, windy or calm …’ He went on to explain that

An Englishman’s notice of the weather is the natural consequence of changeable skies and uncertain seasons. In many parts of the world, wet weather and dry are regularly expected at certain periods; but in our island, every man goes to sleep, unable to guess whether he shall behold in the morning a bright or cloudy atmosphere, whether his rest shall be lulled by a shower or broken by tempest.

So, long before our national addiction to social-media alerts, breaking newsflashes and live online updates, the English had the weather to spice up conversation on an almost minute-by-minute basis.

Enter a particularly English social stereotype: the weather obsessive. An article in Country Life in 29 August 2012 surveyed the type, which has existed since medieval times. ‘Who, from the hotly contended field, takes the Golden Barometer as Britain’s most possessed weather obsessive?’ asked Antony Woodward.

Would it be William Merle, the so-called Father of Meteorology, who had the curious idea of keeping a daily weather journal in 1277, persisting doggedly for 67 years? Or William Murphy Esq, MNS (Member of No Society), Cork scientist and author of little repute, whose 1840 Weather Almanac (on scientific principles, showing the state of the weather for every day of the year), despite correctly predicting the weather for only one day, became a bestseller?

How about Thomas Stevenson, one of ‘the Lighthouse Stevensons’, who measured the force of an ocean wave with his ‘wave dynamometer’ before going on to devise the Stevenson Screen weather station? Admiral Beaufort, perhaps, whose eponymous wind scale sailors still use? Or the artist John Constable, whose ‘skying’ cloud paintings ushered in a new scientific approach to the depiction of the heavens? Dr George Merryweather, inventor, is surely a contender for his 12-leech ‘tempest prognosticator’. Then there’s poor Group Capt J. M. Stagg, on whose knotted shoulders rested the decision of whether to go, or not to go, on D Day. Or perhaps it’s the humble Mr Grisenthwaite, who’s assiduously kept a two-decade lawn-mowing diary (and why not?) that was, in 2005, accepted by the Royal Meteorological Society as documentary evidence of climate change?

In all honesty, I’m surprised that there aren’t more examples of English people obsessed with our weather.

And the funny thing is, we still look to the weather for daily interest – even more so, now we have a myriad of forecasting apps, widgets and websites with names like Accuweather, Dark Sky, Raintoday, Weather Bomb, Radarscope and so on. Rather than eradicating uncertainty about how the day will pan out, forecasts with detailed features surely useful only to a few – such as hourly UV level predictions and dew point information – simply add more variables to a reliable topic of conversation.

‘Lovely day, isn’t it?’

‘Yes! It’s 17°C, but at 3 p.m. it will feel like 12°C because of an east wind blowing in with a chill factor of minus 5!’

Amateur meteorology is a quintessentially English hobby, requiring kit, dedication and lots of specialist vocabulary. All over England people have set up independent weather stations in their own back gardens with hygrometers, anemometers and sunshine recorders. To join this club you need a Stevenson Screen, a sort of box which is the standard means of sheltering instruments such as wet and dry bulb thermometers, used to record humidity and air temperature. Every aspect of its structure and setting is specified by the World Meteorological Organisation, which states for example that it should be kept 1.25m above the ground to avoid strong temperature gradients at ground level. It should have louvred sides to allow free passage of air. Its double roof, walls and floors must be painted white to reflect heat radiation. Its doors should open towards the pole to minimize disturbance when reading in daylight, and so on. As one observer has quipped, ‘It’s like bee-keeping without the bees. The Stevenson Screen even looks like a beehive.’

Often, weather watching is done for a purpose. Pilots, especially of gliders and microlights, need to find optimum windows for their sport. Ditto sailors. Surfing has introduced a whole new meteorological community: wind and waves can be constantly monitored via mobile phone and laptop before the dash down to find ideal surf at West Wittering or Newquay.

One thing the English weather can be relied upon to do is to throw up all sorts of dramatic variations, such as the infamous ‘wrong kind of snow’. This phrase became a byword for euphemistic excuses after the broadcaster James Naughtie interviewed British Rail’s Director of Operations, Terry Worrall, asking him to explain how a period of light snowfall could have caused such severe disruption to services in February 1991. The laughable exchange went like this:

WORRALL: ‘We are having particular problems with the type of snow, which is rare in the UK.’

NAUGHTIE: ‘Oh, I see, it was the wrong kind of snow.’

WORRALL: ‘No, it was a different kind of snow.’

Despite this attention to every nuance of different types of inclement weather, the English always seem to be endearingly ill-prepared for a change in conditions. There is an almost annual fuss about why the gritters haven’t treated the roads before icy conditions strike. Who has a can of de-icer to hand on the first few days it’s forecast to freeze? And who is ever dressed appropriately for weather different from that seen from the window first thing in the morning? We are as addicted to weather-watching as we might be to a long-running soap opera, only in this case the drama comes from being caught out by a sudden shower or ambushed by a freak hailstorm. In July 2006, higher than average temperatures caused a series of power blackouts in central London, closing shops and businesses in the West End, due to the unforeseen amount of electricity used by air conditioners. That could only happen in England. Our weather may have prompted the invention of waterproof outerwear and the Wellington boot, but we rarely seem to be prepared. Perhaps it’s a case of hope over expectation? In Wimbledon, we host the world’s greatest tennis tournament, the only Grand Slam contested on grass – a surface which means play has to stop with every raindrop, unlike the clay of Roland Garros where play continues in drizzle. We persist in picnicking in less than ideal weather. Why not? It’s what we do. We’re English!

Even when prevailing conditions tend to be overcast (England has an average of one in three days of sunshine), the topic itself is never dull. What other country’s newspapers print daily photographs of morning mist, evening cloud formations, thunderous skies marbled with lightning or spectacular moody sunrises? What other language has so many weather-based phrases? The English can be ‘under the weather’ or ‘as right as rain’, ‘snowed under’ or ‘on cloud nine’; we have ‘fair-weather friends’, we ‘sail close to the wind’, find ‘every cloud has a silver lining’ and, if we’re lucky, rejoice in ‘a windfall’. Or so many ways of describing cold: chilly, nippy, fresh, freezing, icy, parky, raw, snappy, numbing, cool, crisp, brisk, bleak, wintry, snowy, frosty, icy-cold, glacial, polar, arctic, sharp, bitter, biting, piercing? And that’s without all the regional dialect or slang. What other nation’s government would commission a survey to find out how often the average citizen mentions the weather? (YouGov in 2011 found that the average Briton comments on the weather at least once every six hours.) Where else is the population so pinned to its meteorological environment?

Well, perhaps there is one reason. The English can be thankful to the weather for many random legacies that affect aspects of our lives.

It was weather that inspired the most popular hymn in the English language, ‘Amazing Grace’. An intense Atlantic storm in March 1748 so terrified slave-ship master John Newton when travelling aboard a slave trader en route to Ireland that he prayed for divine mercy. Twenty years later, Newton, now a minister and ardent abolitionist, referred to his ‘great deliverance’ and described his salvation in a hymn co-written with the poet William Cowper:

Amazing grace! (How sweet the sound)

That sav’d a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.

It was prolonged snowfall in 1908 that resulted in the invention of the windscreen wiper. Gladstone Adams was travelling back to his Newcastle home after driving down to Crystal Palace Park to support Newcastle United against Wolverhampton Wanderers in the FA Cup final. The snow was so heavy he had to continually pull off the road to clear snow from his windscreen. Furious, he folded down the windscreen and arrived home frozen, vowing to invent some mechanical means of keeping the windscreen clear. Three years later he patented a design: it was never built, but the prototype is on display at Newcastle’s Discovery Museum.

We owe so much to unpredictability and variety. Would Turner, perhaps the greatest English artist, be so celebrated as a painter of light and atmospheric effects if he lived in a country without so much fog, light rain, storms and volatile cloud formations? Would the Glastonbury festival be the renowned event it is without the mud and the fashionable way with wellies? The iconic cover of the Beatles’ 1969 Abbey Road album – with Paul, John, Ringo and George filing across a zebra crossing – would not include the quirky touch of a barefoot McCartney had he not whimsically decided to discard shoes and socks due to the sweltering heat on the day it was shot.

The Norman Conquest, 1066 and all that, might never have happened: stormy weather in the Channel allowed William to land unopposed. Wind and a violent storm saved us from invasion by sinking the Spanish Armada in 1588.

The weather throughout history has given telling insights. On 9 February 1649, for example – the day Charles I was due to be beheaded – it was so cold that the Thames had frozen. Records reveal that Charles was led to the scaffold wearing two shirts. He had taken the precaution so that he would not shiver in front of the huge crowd, giving the impression that he was afraid. ‘I would have no imputation of fear,’ he said. ‘I do not fear death.’

I’m not done with the weather in this book. There is still so much to explore, but so far I think we can safely say that as a nation we love to talk about the weather. Or perhaps we love to grumble about it. Our forecasters are household names and often national treasures, and we have people so dedicated to giving us the most accurate information that they’ll risk life and limb in the process. The weather seeps into our national fabric, from our language to our inventions to our history.

No one has put it quite as well as the New Zealand band Crowded House, who might be commenting on the New Zealand weather but it rings so true about our weather:

‘Everywhere you go, always take the weather with you …’