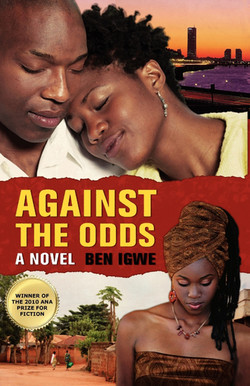

Читать книгу Against the Odds - Ben Igwe - Страница 12

ОглавлениеFour

It was during his second year of teaching that Jamike met Paul Laski when he went to play tennis on the secondary school lawn. Laski was a member of the American Peace Corps who was posted to Aludo’s new Saint Silas Secondary School where the town’s parish priest, Reverend Father Thomas Murrow, was also the principal. Father Murrow had almost given up on his request for a science teacher when the Ministry of Education sent Laski, a man in his late thirties. Laski had a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry from the University of California at Los Angeles and was teaching in a high school in Richmond, Virginia, when he joined the Peace Corps. Africa fascinated him, and while at the university he decided to join the Peace Corps upon graduation. On his application form he indicated he would like to be sent to any English-speaking country in Sub-Sahara Africa, and he was glad to be sent to Nigeria.

Laski was a fitness addict who enjoyed lawn tennis. Jamike learned to play tennis at the Teacher’s College where he was engaged in various sports. Saint Silas Secondary School was not far from Jamike’s home, and he always went there to play tennis, often playing with novices he taught the game. After watching some tennis games one evening Laski identified Jamike as a good player and invited him to a game. They enjoyed playing each other, as both were good at it though Laski had more experience.

Jamike became Laski’s tennis partner and they played on weekends and some evenings. Jamike’s tennis partnership with the American grew into friendship. Most evenings, after a game, Jamike would go to Laski’s house located in the secondary school compound to refresh and talk. He asked many questions about America, some of which Laski found funny or even silly. Jamike wanted to know many things about America because of the fantastic stories about the country. Each person in the village who heard something about America had always added one or two more fantasies. In addition to questions about the land and people, Jamike also wanted to know if everyone in America was a millionaire and if there were cowboys on the streets shooting people.

Jamike was also curious to know if many Americans engaged in magic. He told Laski that when he was a boy, itinerant magicians went from one primary school to another performing amazing conjuring and disappearing acts. Before the magician began his act, he would work the crowd up into frenzy, exhorting them to chant:

Come and see America wonder

Come and see America wonder

Come and see America wonder

Come and see America wonder

As the crowd sang and clapped their hands, the magician would exhort them to sing even louder and faster, while shouting “Abracadabra, abracadabra.” Then he would open his mouth so they could confirm it was empty. After much dancing and joining in the singing, he would start pulling out handkerchiefs tied end-to-end from his mouth. He would further amaze the crowd of school children by igniting a blaze on a rod and shoving it deep into his mouth and down his throat to extinguish the flame. Many children closed or turned away their eyes because they thought the magician would choke.

One Sunday evening when Laski invited Jamike for dinner, they talked about education in America, among other topics. Jamike was fascinated by the differences between education in America and in Nigeria. He was surprised to learn that what was called college in Nigeria was high school in America, and what was called college in America was called university in Nigeria. Jamike showed so much interest in American education that Laski thought it might be good for his tennis partner to be exposed to it. He put a question to him.

“Have you considered studying in the United States?”

“Well, I believe to consider that would amount to dreaming. I cannot even begin to entertain such a dream. I think people usually stretch their hands as far as they can reach.”

“Not exactly, at times people stretch their hands beyond their reach and hope to attain their goal. They may not always succeed, but they wouldn’t succeed unless they tried.”

“You may be right, but I don’t have any basis for hoping to go to America to study. As the saying goes around here, who would give a toad a gift of a coat?”

“That’s funny. You are not a toad, what are you talking about?” Jamike laughed.

“That would be an impossible dream. It was almost impossible for me to finish primary school had it not been for the school headmaster, Mr. Ahamba.”

“How then did you go to get a teaching diploma?”

Jamike always felt emotional when he had to recollect aspects of his growing up. They reminded him of the hardship he and his mother went through, and especially of relatives who were unkind to them. It was a past he would rather put behind him.

“It was the Catholic mission that gave me the scholarship to go to Teacher Training College,”

“How did that come about?”

“After completing primary school, I wanted to go to the city to look for a clerical job. My mother said she would commit suicide if I left her for the city, because she was informed that people who live there easily forget home and parents for a life of enjoyment and rascality. She did not want her only child so exposed. She wanted me to stay in the village and engage in some petty trading or learn some handiwork.”

“What did you intend to be?”

“I wanted to be a clerk. I admired the clerks who were sent by the bishop to invigilate primary school final examinations.”

“Being a clerk is not a bad ambition.”

“It was while my mother and the headmaster considered what I would do after primary school that the parish priest sent for me.”

“Was that Father Murrow?”

“Yes. He informed me that I was one of few students in the diocese selected by the bishop to attend Teacher Training College.”

“Was there any basis for this?”

“It was at the time the diocese needed teachers for local primary schools. The bishop decided to select and train as teachers the top three students in the First School Leaving Certificate Examinations, the final examinations in primary school. In addition to this there was also the diocesan examination set by the Catholic mission. Father Murrow told me I had one of the best results in both examinations. The bishop gave all three of us scholarships.”

“How long did this training last?”

“It was a four-year teacher training course. Each student was bonded to teach for two years in one of the primary schools in the diocese after completion of the course. When Father Murrow invited me to his house and mentioned the possibility of furthering my education, I told him my mother could not afford any more schooling for me. Then he asked if I would further my education if someone else paid my fees.”

“I would,” Laski interjected.

“That was exactly what I told Father Murrow. He then informed me I had the Bishop’s Scholarship to attend Teacher Training College. I could not believe it. He brought out the college prospectus and went through the requirements with me. After that, he gave it to me, blessed me, and wished me well. When I informed my mother of it, she doubted me. Her response was, “I will believe it the day I see you bring out your portmanteau and tell me you are on your way to whatever place you call it.” The following Sunday, during church service, Father Murrow announced my name as one of the students who received the Bishop’s Scholarship for Teacher Training College. It was then my mother believed it.” Jamike noticed that Laski showed keen interest in his story, because he smiled and nodded approvingly many times.

“Your mother is an interesting woman.”

“She did not want to hear anything about more education. She believed I had enough, and she had no illusions about how expensive education was.”

“I would say you have been lucky. It is an amazing story.”

“That is my story, and I thank God.” Jamike asked for a drink of water.

“I believe I told you in one of our conversations that I will be returning to the United States at the end of this year when my tour of duty ends. I intend to obtain an advanced degree and later look for a teaching job in a college in a rural part of the country. If I do I might be able to help you come to the United States to continue your studies. I am not making any promises, but I will try. I think you will benefit from an American education.” Jamike was baffled.

“Are you serious? Even if in the end it is not possible, the thought alone is sufficient. But I tell you, that will be in my wildest dream. As they say, seeing is believing.”

“No, just think positive about it. It is when you believe strongly in a thing or want it badly that it actually comes to pass. It is a fact that is not easily appreciated.”

“You are right. The Igbo people have a saying similar to what you just said. They say that whatever one affirms, his chi or god will also affirm it. Now, I am going to believe it will happen. I will be in America! Alleluia!” Jamike hit both hands on the table; they laughed and shook hands. For the rest of that evening before he went home with a flashlight, they played a card game.

Paul Laski left for the United States in December of that year and within six months after his departure a civil war broke out in Nigeria. The Eastern part of the country seceded and declared itself the Independent Republic of Biafra. The war lasted thirty months, and during that time young men were conscripted into the armed forces. First, Jamike worked in civil defense and later for CARITAS, the Catholic relief organization. He assisted Father Murrow in overseeing the distribution of scarce food items like salt, stockfish, corned beef, corn meal, milk, baby food, and other essential commodities needed for life’s sustenance. Uridiya’s friends enjoyed her generosity during the war.

The ravages of war did not get to Aludo, located in the heartland, and villagers believed that had to do with their ancestral name, Aludo, which meant land of peace. Villagers could hear the sounds of heavy military artillery like mortar shells from the faraway city of Umuahia. One time a fighter jet plane flew over Father Murrow’s house but dropped no bomb. The two-storied building had a huge Red Cross sign painted on the zinc roof. Apart from one letter Jamike received from Laski before the war broke out, the two friends lost touch for the duration of the war. In the meantime, Laski had gone on to the Pennsylvania State University to get a doctorate degree in science education and began teaching at Regius State College in rural western Pennsylvania.

When the civil war ended, Jamike received Laski’s letter inquiring whether he made it through the war. He was worried about his friend because of horrible pictures of the war on television and news stories from Voice of America. These and the images that appeared in magazines and newspapers, gave Laski concern for his friend. Soon correspondence was re-established between them. Shortly after their renewed contact, Laski informed Jamike that he was leaving for a two-year teaching contract in Okinawa, Japan . For about six months, Jamike did not hear from Laski. Once he settled in his new teaching position, Laski wrote Jamike, and their correspondence continued until Laski returned to the United States.

Not long after Jamike began teaching, Mr. Ahamba suggested that he inquire from older and more experienced teachers in the school about the correspondence courses some of them were taking from Woolsey Hall and Rapid Results College in London, England. These courses prepared one who did not attend or finish high school to sit for the Ordinary Level of the General Certificate of Education examinations as an external candidate. He urged Jamike to start such a course so that after he passed the necessary examinations, he could move up to become what was called a pivotal teacher with a high school equivalent and a teacher’s training certificate. It would enhance his status and prestige. Two years later, Jamike obtained the General Certificate of Education in four subjects: Economics, British Constitution, English History, and Government.

Laski returned to Regius two years later. Not quite three months after he was back in Regius, Jamike received an application package that included forms for tuition remission for Regius State College.

Fate was about to smile again on both Uridiya and her son in a way that would marvel the village. No one believed that the little boy who walked about naked in the village, hunted rodents, chased rabbits and squirrels wherever he sighted them, and who many didn’t think would survive ill health as a child, would one day become a teacher. And little did they think that Jamike would be the one to make the village proud, for he would now travel to America to further his education. He would be the first in his village to set out on an educational mission to a land that the most imaginative villagers could only dream about ―a land they had only heard by name, a fairyland, America.