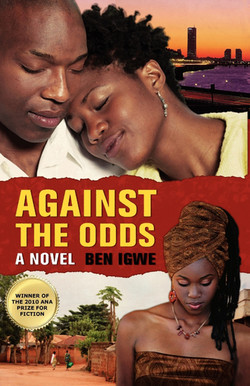

Читать книгу Against the Odds - Ben Igwe - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSix

Jamike was twenty-seven years of age when he left for America. Villagers gathered in the compound on the morning of his departure. There was movement of people here and there. Some huddled to talk. It was not difficult for an outsider to perceive that something important was going on. Passersby stood around the entrance to the compound trying to find out what happened. People moved about, some with their hands clasped and others with gloomy faces. Uridiya wept with both joy and sadness as she embraced her only child, now a man.

Jamike was ruggedly built with broad shoulders. He was a charming young man with a broad face and a full crop of dense hair that reminded older villagers of Nnorom, his late father. Since his childhood, Jamike often heard people say that he was every inch like his late father. The only resemblance to his mother was his large eyes. Jamike’s body exuded strength. As he grew older, especially in his late teens, his height and perceived strength enabled him to ward off people who might have had any intentions of doing harm to his mother.

With tears in her eyes, hands trembling, Uridiya knelt down, clutching her son’s legs in her hands. Looking up at him, she raised her two open palms to his face, and said:

“Jamike, look into my heart and into my soul. Remember your mother. My life is in your hands now. Do not do anything that will cause my death if I hear it. I want to stay alive and live long enough to hold your child, my grandchild, on my lap. Remember the headmaster who help ed you. Know that without him you would not have been able to complete elementary school. If you forget everyone else, do not forget him and his family. He saved us many times. I know you will not forget anybody who took me for a human being. Almighty, the creator of heaven and earth, will guide and protect you.”

Tears welled in Jamike’s eyes. Relatives and passers-by that witnessed this spectacle were moved beyond words. When they learned that he was going to be away for many years, the emotions were mixed. The first son of the village to study overseas was leaving for America. It was a thing of joy, yet some looked sad, as if they wished he would stay in the village with them. As a teacher his presence in the village was a thing of pride and conferred some status on them. Some of the old kinsfolk were downcast because they probably thought they might not see him again. He felt the same way, too, as he embraced old kinsmen and women―some of whom walked with canes.

Many relatives followed him to walk the two-mile distance to the tarred road junction where he boarded transport. Uridiya would have preferred not to see him board the bus. The trip to Onitsha from Aludo took nearly three hours. At Onitsha he boarded a bus that made the Lagos journey in ten hours. A contact the headmaster had made with an old schoolmate bore fruit. Mr. Kamalu was at the motor park and had waited nearly two hours before Jamike’s bus arrived. It was his second time at the motor park that Friday. The description Jamike had of Mr. Kamalu made it easy to recognize him. It was almost eleven o’clock at night when they got to Kamalu’s home in Apapa. It was the next day that Jamike met his host’s family.

Mr. Kamalu arranged for the taxi driver who took Jamike to Lagos International Airport, where they arrived at six o’clock in the evening. The driver was a neighbor, and Mr. Kamalu gave him strict instructions not to stop anywhere but the airport. Once he came out of the taxi Jamike was harassed by porters who wanted to carry his small suitcase through the throng of passengers, panhandlers, pickpockets, and thugs to join the check-in line. He held on tight to his suitcase as he entered the terminal building. Jamike was overwhelmed by the huge airport terminal, the large number of people, the hustle and bustle, restaurants, stalls filled with crafts and assorted goods travelers might need, shoe shiners, male nail manicurists seeking business, money changers, and, perhaps, money-doublers too―all manner of people.

At exactly eight o’clock, check-in began. Once he was checked in, Jamike went through customs and immigration and proceeded to the waiting area. He did not talk to anyone, because he did not know anyone. He was still apprehensive about whether or not his suitcase that was taken from him at the check-in counter would be in America when he got there. He consoled himself because other passengers gave their luggage to the check-in clerk. Boarding began at ten o’clock, and it was past midnight when the aircraft’s turbo engines began to rave as it readied to move. Many thoughts ran through Jamike’s mind as he sat quietly in his economy-class seat.

“So this is it. I am leaving home,” he mused. “Leaving with no idea of when I will be back. I wish it was not midnight so I can see the bushes and trees on the horizon.” What he saw instead were dazzling, colored lights on the runway and the blinking lights on the wings of the airplane. Jamike Nnorom was not sure whether this was a dream or reality. He believed that God has a plan for everyone and it is etched on the palms of each person’s hands. His people call it “akalaka” and believe that a person’s fortunes and tribulations are in accordance with the meaning of the configuration of the lines on his or her palm.

Pan American Airways Flight 114 to New York moved slowly in a slight drizzle on the silent, undulating runway, sometimes almost slowing to a halt. It took one turn, and then another before it finally came to a squeaking halt. The runway it faced was studded with blue light bulbs and looked so straight and tapering it seemed it ended in infinity. The aircraft heaved, raved, and roared to a deafening sound as it sped away at breakneck speed, shattering the silent night. Jamike made the sign of the cross, covered his face with his palms and prayed as he always did whenever he set out on a journey. The plane lifted itself up and was airborne. Already he was overwhelmed by the size of the supersonic jet and the hundreds of passengers on board and wondered how it would keep itself in the air for the number of hours he was told it took to be in America.

Jamike Nnorom, the son of Uridiya, a widow, who struggled hard to survive with her child, despite the rancor of devilish relatives, was on his way on a journey that would change him forever. He was in an airplane that no one in his entire village had seen before. Jamike remembered that as children they would rush out of the compound to strain their eyes looking up in the high sky if they heard the rumble of a nearly invisible airplane. The only thing they would see was a tiny object thousands of feet in the clouds. At these times the youngsters and some old women prayed the pilot for some generosity. Some would say, “Aeroplane kindly drop a bag of money to me.” And others said, “Aeroplane kindly drop a bag of money to us.”

Jamike, who had an aisle seat, wished he sat near the window so he could lean against it and sleep, but he did not know he had to request it at the check-in counter. The passenger occupying the window seat was an elderly woman who, he later found out from her escort, was visiting America for medical treatment. Her face appeared painful. Her jaw was out of symmetry, perhaps, due to a recent stroke. She appeared anxious and nervous. Jamike took a quick look at the woman and greeted her, but he might as well have been speaking to a wall. He came to the realization that when people are in pain or preoccupied with life’s uncertainties, response to a stranger’s greeting would not be of priority.

It was not long before a man came and spoke to the woman in a language not understood by Jamike, apparently to find out if she was comfortable. The man introduced himself as the woman’s escort. He covered her with a blanket up to her neck and appealed to Jamike to assist the woman who he said was going to receive medical treatment in America. He tried to engage in a conversation with Jamike, but his thoughts were on what he was experiencing and on the village he’d just left. He was not prepared for that conversation. The first time in an aircraft, going to an unknown land, Jamike’s mind was occupied with his own private fears. He was thinking about what he would do if this aircraft fell into the water, because he learned that they would be crossing the Atlantic Ocean. He thought about what he feared to think about, whether or not he would see his mother again. To Jamike, engaging the man in conversation rather than being concerned with his inner thoughts would amount to chasing a mouse that ran out of a burning house instead of focusing on putting out the fire, as his people would say.

Once he was fairly comfortable, or rather had adjusted to the discomfort of his narrow economy seat, Jamike kicked off his shoes and stretched his legs under the seat in front of him. Now and then he would try to sleep, but whenever there was a noticeable turbulence of the aircraft, he would open his eyes to check on the reaction of other passengers. Since the pilot informed them that the flight to New York was across the Atlantic Ocean, Jamike had focused some thought on that. He did not know how to swim. What would happen if the plane fell into the ocean? If any such thing happened, he thought, that would be the end of him, and as an only son their household and lineage would permanently come to an end after his mother passed away.

Jamike’s other thoughts were of the village and the people he had known, and the village square that was the center of his childhood and adolescent life. When would he be able to see all that again? What would his mother be feeling that night and in the days to come? She must have been lost in thought of him. But Jamike was glad the headmaster would check on her the following morning. What of the old village church where he sometimes taught catechisms to small children? What of Oriaku, the old blacksmith, for whom he used to fire the mud furnace when he was a youngster? Again, he thought about his inability to swim as they were crossing the Atlantic; he remembered that knowing how to swim might not be helpful to even the best of swimmers, because they would not know where to swim to in the vastness of an ocean with no horizon in sight. These and other thoughts interfered with his attempt to sleep. He kept awake and reminisced.

As he relaxed, Jamike reminisced about the farewell party that the villagers gave him in the church hall. The remarks made by the elders contained a litany of what Jamike should do and should not do when he gets to America. As the elders spoke, Jamike’s mother lapsed deep in thought, both palms holding her chin, a favorite position when in thought, her facial expression wavering between sadness and joy.

Ikonne, an elder, who spoke at the reception, told Jamike never to forget his origin, village, or his country. There were many good things, they heard, that were sweet in America. He should not allow himself to be deceived by such things. A second elder told Jamike that they had heard that American women were very beautiful, their skin so shiny it reflected the image of the beholder. “So are our own women, too, if you look carefully and closely,” he told him. “Remember, if you say your mother’s soup is not good enough, people will believe you and help you spread the word.” He continued:

“Do not go there to marry a foreign woman. I say to you, look around this hall. Apart from the young ladies here who are related to you, there is no type of woman you will not find among them and in all Aludo. Big ones are here, so are small ones. Tall women are here, so are short ones. There is no shape you will not find. As you see them here, so will you find them in all the villages from which we marry. Just point to the one, and we will marry her for you before you come back. Or if you want, we can send her over there. You know, if you marry a wife from there your mother will die of heartache before you bring her home. American people have a language we cannot speak or understand. If you marry one of them, you have to bring Uridiya to America to learn the language too.” There was plenty of laughter.

As these remarks were being made, Uridiya murmured a few sentences to the effect that if her son would want to cause her death, he could go ahead and marry a foreign woman. One of the oldest men in the village stood up to speak. The hall was now rowdy but he was not going to allow that to deter him. He kept standing with his walking stick in hand, waiting for the noise to die down. That did not happen until the headmaster stood up and clapped his hands many times to get their attention.

Raising his wine cup made from a cow’s horn, the old man invoked the spirits of the ancestors in a libation. He implored the spirits to share in the food and drink. He committed Jamike to their hands, asking them to protect and guide him as he set forth on a journey that was just a dream to the villagers. Since this had not happened to them before, it might be for the good of the village. To everyone’s surprise the old man added, “Everybody has given you all kinds of advice. I am sure your ears are full by now. They have all told you not to marry an American woman. But I tell you the opposite. If they are human beings like us here, nothing stops you from marrying one of them if the two of you agree. If we cannot hear what your wife says, maybe she will teach us.”

He joked that by the time Jamike would return to his fatherland, he too could be talking like American people, and they all might need an interpreter to understand him He turned to Jamike’s mother and told her,

“If your son comes back with an American woman and you do not know what to do with your daughter-in-law, you can send her over to me. My wife has been long dead as everyone in this village knows,” he said, “I think an American woman could prolong my life, and those waiting for my death would have to wait longer or even die before me.” Continuing, he added,

“There are many things a white woman can help me to do. She can stoke the fire so I can keep warm at night. I can teach her how to rub my aching back. I don’t have to speak her language to do that. She too can teach me the rascality men and women engage in these days. I am not too old to learn that. I know some of you are expecting my funeral, but I tell you, I am not dying yet, not if you give me a woman from the white man’s land to take care of me.” He sat down and the hall broke loose with mirth!

Jamike was about to respond to the advice given to him, when the traditional head of the town arrived. He greeted all the people in the traditional way with his wide leather fan adorned with peacock feathers. Once he sat down and was recognized, Chief Ekele made his remarks.

“I greet all who came to this happy occasion. We are glad that Jamike has passed all the examinations required to go overseas to study. Your son, Jamike, has done what no one expected. We thank him and advise him that the road that has been opened for him should not be closed. He should not close it for others as some people would do, but instead he should keep it open. America is not for one person, and we will like for others to go there too. As our custom goes, the Chief’s council will meet to set a date to prohibit everyone from harvesting their palm trees. This prohibition will last for eight weeks.” He continued,

“After this period, the village will harvest them communally, and money realized from the sale we will send the sum of one hundred pounds sterling to Jamike.” Then he asked them, “Is this our custom or not?” The villagers answered that it was their custom. He continued, “I believe we have done this for one or two of our sons studying in our country. We now have to pray for good harvest. Anyway, I know that those making it possible for Jamike to go to America will see that he completes his education. Going to America is not a play matter for a mother and her child, as we say. Carry on and enjoy the merriment, as I have to leave because I came out in the middle of a meeting to be here. You know that the absence of the Chief from this type of occasion would be misunderstood.”

Chief Ekele left the hall without eating or drinking. When Jamike began to speak he thanked the chief who had already left, for his presence and kind words. He said that he has heard all their advice and remarked that he would only pray to God to hear their prayers for him. He told them he would not forget where he came from and he would not eat up everything presented to him in America. He would surely save and bring back some to them, as only a sensible child would do. Whatever achievement he would make in America would not be for him but for them.

Then he added that as the elders said, “When a child picks a snail in the bush, it belongs to the child, but when he gets home, the snail belongs to the village. Marrying or not marrying an American or foreign wife is not the reason I am going to America. I recognize that my primary mission is to receive an education, and that is what I am going to face when I get there.”

Recollections of his send-off party in the church hall that Sunday afternoon came back to Jamike vividly as he sat in the plane. He thought of his mother and prayed that God would keep her until he returned. Jamike looked at his watch, a gift from Mr. Ahamba and his wife, Asamuka. The headmaster was around to comfort and encourage Uridiya the morning after Jamike left for a place she referred to as “white man’s land,” where Uridiya already said neither her hand nor her voice could reach any longer. To the villagers, anywhere overseas was regarded as white man’s land.

Distance meant nothing to Uridiya. If America were nearer, maybe her voice would reach there. When Jamike was a youngster she would call him at the top of her voice if he went to a faraway bush to cut firewood, or even to the stream deep in the valley to fetch water, and failed to return when she expected him. Uridiya would walk up and down along the village dirt road and narrow paths, stretching her voice to call Jamike while passersby would wonder if she was sane. In those instances, she would tell them, “I am calling my only seed from God, and I am not calling him with your voice. You have to bear with me; you know the elders said that if a blind person fails to pick the Udala that he felt with his foot, how could he be sure he would stumble on another.”