Читать книгу Land Rover: The Story of the Car that Conquered the World - Ben Fogle, Ben Fogle - Страница 7

INTRODUCTION

Оглавление‘Do not go where the path may lead,

go instead where there is no path and leave a trail’

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Sometimes you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.

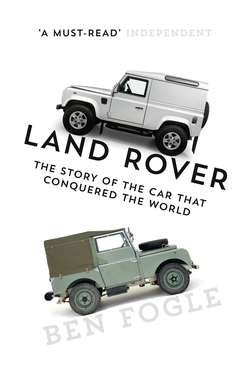

At 9.30am on 29 January 2016, the 2,016,933rd Defender rolled off the production line at Land Rover’s factory at Lode Lane, Solihull, on the outskirts of Birmingham. It marked the end of 67 years of continuous production of the world’s most famous vehicle. The final Defender.

In all those years, the workhorse Defender had served farmers and foresters, armies and air forces, explorers and scientists, construction and utility companies – in fact, everyone who needed a good, honest vehicle that would do a good, honest job anywhere in the world. And there were a lot more people who bought one just for fun, too – for its sheer brilliant off-road ability and austere utilitarian attitude that made it so different to the rest of today’s homogenised, jelly-mould automotive offerings.

‘Jerusalem’ was sung through the factory line as generations of engineers, mechanics and factory line workers paid tribute to the Land Rover Defender. This was a funereal send-off for a much-loved car that had conquered the planet. Media, journalists and film crews had descended from around the world to record this death knell. The world held its breath as the last ever Defender was driven silently out of the building.

This was an end that was marked by tears and sorrow, as Land Rover enthusiasts bade farewell to a familiar friend and the historic production line that had produced it fell silent.

The world mourned. This was the day the real Land Rover, the successor to the Wilks brothers’ 1948 original, died.

It is said that for more than half the world’s population the first car they ever saw was a Land Rover Defender. As quintessentially British as a plate of fish and chips or a British bulldog, the boxy, utilitarian vehicle has become an iconic part of what it is to belong to this sceptred isle. It is a part of the stiff-upper-lipped British psyche; it never complains, and neither do we.

You climb into a Land Rover – literally; in fact some people even need ropes to hoist themselves up into the rigid seats. The doors don’t seal properly, and freezing cold rainwater, overflowing from the car’s gutter (they really do have a gutter) cascades down your neck as the flimsy aluminium door invariably closes on the seat belt that dangles out of the door. The dashboard consists of a series of chunky black buttons and two analogue dials. Without heated seats, climate control options are freeze or fry. The windows ALWAYS mist, even if you hold your breath. I have to pull up a metal antenna from the bonnet to pick up radio, which I can only receive while driving at 30mph. If I crank her up to her limit of 60mph, the noise from the engine, gearbox, transfer box, differentials, tyres and the wind is deafening, and too loud to have a conversation let alone listen to anything from the speakers. There is no coffee-cup holder or hands-free. The gears grind and the seats cannot be tilted.

So on the face of it there is not much going for the Defender. It is noisy, uncomfortable, slow, uneconomical and, according to the USA, dangerous. So why is it that I, along with millions of other people around the world, am so hopelessly, obsessively in love with this car?

The Land Rover is an integral part of the fabric of our society, a part of the furniture. Nothing lasts forever, but some things come close. The Defender has survived the decades largely unchanged. It transcends fashion while somehow epitomising it. It has an ability to neutralise rational thought or expectation, and it has avoided the homogenisation of our vehicles in modern times.

The Defender is a beacon of safety and security, too. It is favoured by the military, the police, the fire service, NGOs, the UN, the Royal Palace, the Special Forces and explorers alike. These vehicles have discovered new regions, won wars and saved lives. Across the world, the Land Rover symbolises durability and Britishness, with her diversity and rigidity. It is estimated that three-quarters of all Land Rovers ever built are still rattling noisily across country somewhere in the world.

The Defender is a national treasure. We are reassured by its understated presence. It inspires a second glance but never a stare. Unshowy, unpretentious and classless, it is the car in which you can arrive at Buckingham Palace, a rural farm or an inner-city estate.

Over the years I have encountered Land Rovers in the farthest corners of the world. From steamy tropical jungles to remote islands, I have bounced across lonely landscapes in dozens, perhaps hundreds, of Land Rovers, many of them decades old.

Around the world, the Land Rover has become as much a part of the African savannah as acacia trees and elephants. The UK was still a colonial power at the Defender’s inception, and the car quickly spread across the Empire; from Tristan da Cunha, where a lone policeman patrols the island’s one-mile road in his trusty Defender, one of only a handful of vehicles on the island, to the Falkland Islands, which boast the world’s highest per capita Land Rover ownership – one for each of the 2000 residents who live there, earning itself the moniker Land Rover Island.

I have driven through the muddy trails of the Amazon basin and across the deserts of Chile in ancient Land Rovers bound together with baler twine. When my young family first came to visit me while I was working in Africa, there was never any question that we would embark on an expedition across the muddy plains of the Serengeti in anything other than a Defender. It always seems incredible that these international workhorses that have crossed some of the most challenging of landscapes in remote corners of the world originated from a former sewing-machine factory in Solihull, near Birmingham. Such an inauspicious birthplace for arguably one of the world’s most iconic vehicles.

When I drive through London in my Land Rover I get stopped not for my autograph or a selfie but for a photograph of my car. I have lost count of the number of notes slipped under the windscreen wiper with offers to buy my beloved car. The children love it. The dogs love it – and so do two million other people in the world.

Everyone from Fidel Castro to the Queen drives a Land Rover Defender. Idris Elba made his entrance at the 2014 Invictus Games’ opening ceremony aboard a trusty Defender. Ralph Lauren, Kevin Costner and Sylvester Stallone all drive the rugged vehicles. And now, after 67 years and two million vehicles, the Land Rover Defender has ceased production. It is ironic that the vehicle is more popular in death than it was in life. Interest has reached fever pitch for this icon of Britishness; it is a vehicle that transcended its original remit to knit itself into the fabric of the nation that created it.

A vehicle that can drag a plough, clear a minefield and carry royalty, the Land Rover Defender transcends the rapidly changing world in which we live. As cars become rounder, curvier and shinier, the Land Rover Defender still looks like a child’s drawing of a car, with its boxy shape. To climb into a Defender is like stepping back in time into a simpler, classier world.

The Defender was a car that didn’t just defy the fickle face of fashion but also changing mechanisation and economics. It was a car that was handbuilt until the end. It took 56 man hours to construct just one vehicle. Two original parts have been fitted to all soft-top Series Land Rovers and Defenders since 1948: the hood cleats and the underbody support strut – but these are just two of the over 7000 individual parts that make up each Defender.

This is a car that is instantly recognisable from its wing mirrors to its wings. Indeed, workers on the Land Rover production line have their own nicknames for parts of the vehicle: for example, the door hinges are known as ‘pigs ears’ and the dashboard is the ‘lamb’s chops’.

So what is it about this vehicle that has spawned such an obsessive, loyal following? How did the Land Rover so successfully take over the world? In some ways the Defender mirrors many of our national traits; stiff-upper-lipped and slightly eccentric. In the spirit of the great British explorers Scott, Shackleton, Cook, Livingstone, Fawcett and Fiennes, the Land Rover was a twentieth-century progression of the age of exploration.

The car has spawned an industry that includes dozens of publications, car shows and even model cars tailored to the passion of those who dedicate their lives to the Land Rover. In order to understand why this car is such a national treasure and excites such passion, I decided to embark on a road trip of my own in my trusty Land Rover to meet the people who live for this marque – the enthusiasts, the designers, the military, the police and the explorers who glory in this bastion of quintessential Britishness.

A Land Rover is a living breathing thing. The vehicles become characters. We name them. We learn their unique quirks and foibles. It is a sort of love affair. I know plenty of men who remember more about their old beloved Land Rovers than they do their ex-girlfriends. These cars seduce us with their charm – they are not supermodels, they are dependable, robust and loyal. There is a unique and almost unquantifiable relationship with a Land Rover. It is an emotional attachment like no other. How can a man-made object have such power over us?

Every Land Rover has its own unique story to tell. Here, in these pages, is the story of the world’s favourite car and how it conquered the planet and the hearts and souls of those who inhabit it … and me.