Читать книгу Land Rover: The Story of the Car that Conquered the World - Ben Fogle, Ben Fogle - Страница 9

A LOVE STORY

ОглавлениеYou never forget your first Land Rover. It was a rusty grey pick up that seemed to be held together with baler twine. The doors didn’t close properly and baler twine was doing the job of holding them shut. Inside, her seats were ragged and torn, transformed into a fabric reminiscent of Emmental cheese by the farm rats. The front windscreen was cracked and there was a large hole where a stereo had once sat. A thin coat of dust coated the interior and an even thicker layer of mud swamped the footwells. Various gloves and farm tools had been wedged into any spare space. She had a sort of musty, fuely smell that overwhelmed the senses.

On starting, she would rattle and vibrate violently. A thick black cloud of smoke would temporarily envelop the whole car with a toxic cloud of diesel fumes that threatened to choke you as it seeped through the gaping seals where the doors failed to close.

I must have been about 9 or 10 years old; I was on a farm in West Sussex where my parents had rented a tiny cottage, which was next to a working beef and dairy farm that the farmer operated with the help of an ancient Land Rover. I loved that smelly old broken vehicle, built purely for functionality.

So I have a confession to make. My first car was not a Land Rover. My parents didn’t drive one, nor did I learn to drive in one. Truth be told, I’m not even that into cars. I suppose to understand how I have come to write a book about the Land Rover, I should begin by exploring my own history with the automobile.

Our first family car was an ambulance. Not any old ambulance, but an animal one. My father, a vet, bought a Honda camper van that he converted into the ‘Mobile Animal Clinic’, a slogan which was emblazoned down the side in green ink. He wasn’t allowed blue flashing lights so the van had a green one instead. She had a little operating table in the middle and oxygen tanks around the sides. Although she was technically a caravan or a mobile home, she was like a little box fitted behind a tiny cab. The seats in the back were configured around the operating table, which meant that not only could we use it to do our homework on the way home from school but we could play endless games of monopoly during long car journeys. She was, without doubt, the most distinctive vehicle on the school run.

Sad was the day when my father retired our little animal ambulance, to be replaced by the Space Cruiser, with its state-of-the-art electric retractable roof. At the time, Toyota was one of the most advanced vehicle manufacturers in the world. Those were the days when Japanese vehicles were really coming into their own, and I think my father had been seduced by the Japanese during many of his lecturing tours. Everything in the Space Cruiser was electric – windows, sunroof – I can still recall my sisters and I standing on the back seat, with our heads protruding through the open roof as we drove through the country lanes of Sussex. Of course, driving regulations and safety requirements were a little more relaxed in the 70s; this was still the era of non-obligatory seat belts and of rear-facing seats in Mercedes-Benz. My abiding memories were of dozens of children crammed into cars and wedged into seats, often sitting on laps, heads lolling out of the open windows. Ah, those were the days!

Alongside the practical vehicles that our family owned, my mother had a lifelong love affair with the Italian Alfa Romeo. Her first was a blue model which she lovingly drove for nearly 20 years until she replaced it with a red Alfa, complete with spoilers and fins. My father could never understand her passion for the Alfa; they were expensive to run and, in his eyes, they weren’t even particularly good cars. My mother never agreed. She loved her Alfa.

Apart from my mother’s passion for the Alfa, cars were not a Fogle family obsession. They were merely functional; a means of getting from A to B or for transporting wounded animals.

One of my friends had a father who owned a Caterham. I can still remember the joy and exhilaration of being driven down a dual carriageway at more than 100mph with my head sticking out, free in the open air of the convertible. Bugs stung against my cheeks as we sped across Dorset.

When I turned 17, I decided it was time to get my driver’s licence. Looking back, I didn’t go about it in a particularly clever manner, though. Most people think logically about such important milestones and plan it with their family’s help. I was away at boarding school and short of funds so I decided to do one occasional driving lesson at a time, and then do another one once I had saved up enough money. This system worked well at first, but soon having just one lesson a month began to have detrimental effects. I have never been a quick learner and whenever I had a lesson it felt as if I was starting from scratch. This soon became apparent when I failed my first test, and then the second and the third and the fourth …

It took seven tests before I finally passed. I think this story nicely illustrates several points. First, that I am quite a stubborn individual, and second, that I really wasn’t into cars.

For the first year after I passed my test my father kindly lent me the silver-bullet Toyota Space Cruiser whenever I needed transportation. It was without doubt the most uncool car to be seen at the wheel of, but it did the job and I can remember driving piles of friends down to Devon and Cornwall in it. It was, as my father often reminded us, very ‘functional’.

The first car that I owned myself was a grey Nissan Micra. It was the archetypal bland, homogeneous car, but it was a very generous eighteenth-birthday gift from my father, who quite rightly pointed out that it was, as ever, economical and functional. My mother had tied a giant red ribbon into a bow on the roof when they presented it to me. I climbed in immediately and drove it to Hyde Park in Central London – and straight into a red Volvo. Within an hour of getting my first car it was a near write-off and was being towed away by a recovery vehicle. Once repaired, though, my little Nissan Micra served me well. I took that little car everywhere – to Scotland, the French Alps, Spain. She was a trustworthy little vehicle that didn’t break down once in the seven years I drove her.

Despite my early difficulties in learning to drive, I loved driving. As a family we used to drive a lot. Every weekend we would pack up the Mobile Animal Clinic, and latterly the Space Cruiser, with my two sisters, our two golden retrievers and Humphrey, our African grey parrot.

In the summers, my sisters and I would be packed off to live with my paternal grandparents in Canada, where we experienced another approach to driving. My late grandmother, Aileen, was anything but your ordinary grandparent – agile and strong until the day she died, aged 100, she always stood out from the crowd, so it is probably no surprise that her car of choice was a sports car, a green Camaro with a V8 engine.

The ritual packing of the car would continue on the other side of the Atlantic, as Canadian dogs and cousins were all herded into the tiny sports car for the two-hour journey from the city of Toronto out to my grandparents’ little summer cottage on the shores of Lake Chemong.

Land Rovers did not cross my path again in any memorable way until 1999, when I took part in Castaway for the BBC. This programme was a year-long social experiment to see whether a group of urbanites could create a fully self-sufficient society from scratch. For this, we were marooned on an uninhabited island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, in the Western Isles.

It was a remote, rugged place, and we were left there, isolated from the outside world. We had no internet, telephone nor television. It was just us and the windswept landscape of Taransay. The island had once been inhabited, but all that was left of its one-time occupation was a small farmhouse and an animal steading. Dotted around the island were remnants of its earlier history, in the form of black houses, their crumbling ruins a reminder of the crofters that had long ago worked the land.

The island topography was boggy and mountainous. There were no paths, tracks or roads, and crossing the island would involve a yomp through knee-high bogs and up the steep flanks of the hills that dominated the landscape. The absence of roads made the remains of the island’s sole vehicle even more remarkable and curious. Hidden near the animal steading that we had converted into the kitchen and communal area was the rusting body of a Land Rover Series II.

That Land Rover confused me more than almost every other aspect of island life. I couldn’t begin to fathom how such a vehicle would have been used, and why it was there. It wasn’t just the logistics of getting the vehicle onto the island that baffled me; rather, apart from the small area around which we built our settlement – which was about the size of two football pitches – I couldn’t imagine how the Land Rover would get across country. It seemed impossible that any vehicle, even a Land Rover, could make its way through this inhospitable geography.

The car had long since lost its engine, and its skeleton-like remains made a perfect place for the children to play and pretend they were driving somewhere. That island had a strange effect on all of us and even I used to sit in that dilapidated car and imagine I was on a journey, driving across a vast wilderness.

It was then and there that I resolved that I would one day get a Land Rover.

As our only communication with the outside world was via letter, and as the end of the year and the experiment loomed large, I wrote to my father to ask him to help me find a Land Rover for my return. When the end came it was a bittersweet moment. I longed to leave that island but I also worried about adapting to life back in the real world. For a year we had been isolated from the rest of the world, and suddenly, come 1 January 2001, having been stripped of our anonymity, we were about to be thrust back into civilisation – not to mention the public eye. It was a daunting prospect.

We were helicoptered off the island in a carefully choreographed live TV broadcast. I was last to leave. Tears streamed down my cheeks as we crossed that tiny body of turquoise water that separated us from the next main island of Harris.

Several dozen journalists and photographers had braved the Hebridean winter to gather on Horgabost beach ready for our arrival. It was the beginning of a new life in front of the media glare – and it scared me.

We transferred into coaches and began what seemed like a victory drive across the island to the Harris Hotel, where we would begin our decompression. I can’t begin to tell you how strange it was to be back in civilisation. A press conference was convened in the hotel’s dining room and we were thrust into the hungry grasp of the British press. It was quite a revelation. The questions. The spin. The stories. The money offers. The exclusives. Rival newspapers vied to outbid one another to get the scoop. We castaways became pawns in a game about which we knew very little. We didn’t understand the rules and we had very little help to pick our way through the minefield.

We were due to stay in the hotel for a few days to acclimatise and spend time with the show’s psychologist, but I found the whole experience overwhelming.

‘There’s something waiting for you in the car park,’ one of the show’s executive producers told me.

I escaped the claustrophobia and heat of the hotel and strode out into the wind and rain of the small gravel car park. There, tucked away in the corner, was the unmistakable shape of a blue Land Rover Defender. I pulled the handle of the unlocked door and climbed in. A set of keys had been ‘hidden’ beneath the sun visor. A smile enveloped my face. It was the Land Rover smile – more of which later.

I relaxed. It was as if all the fears and worries that had been brewing in that small hotel disappeared. I had my first Land Rover. It may seem strange, but I had no idea how it had got there, who had bought it, how much it cost or even if it really was mine. The world had become such a strange place that it never even occurred to me to ask.

While the rest of the castaways had been booked to fly back to civilisation from Stornoway, I had worried about flying back with my Labrador, Inca. She had only known freedom for a year; she hadn’t worn a collar nor been on a lead in that time and I couldn’t bear the thought of confining her to the hold of a plane in a cage, so driving seemed the natural solution to the problem.

My first night in a proper bed was not the luxury I had been anticipating. I found the central heating stifling and oppressive and the bed was far too soft – even apart from the fact that my mind was spinning and reeling. I was confused and, if I’m honest, I was scared, too.

I’m not sure what came over me or even why it happened, but I woke up in the middle of the night that first night – and left.

In retrospect it was completely out of character. I had planned to spend several more days with the show’s execs and the gathered journalists for interviews and photo shoots, but I was overwhelmed by the new situation I found myself in. So, quietly, I packed the Land Rover with my worldly possessions and Inca and placed the key in the ignition. The engine turned several times and then … spluttered to a stop. Several mysterious lights illuminated the dashboard. I tried again, willing the car to start, then finally the engine choked and spluttered to life. The whole car shuddered and vibrated. Inca sat in the passenger seat, her head lolling out of the window as we rolled out of town on the long journey home.

It was midwinter and sunrise was still hours away. I had been in plenty of Land Rovers through the years but this was the first time I had driven my own one. I felt a freedom that I had been deprived of for more than a year – a sense of liberty and sheer happiness at being able to explore, unfettered. That island had been like a prison, we had been confined by its watery limits, but here, now, aboard my mighty Land Rover, I felt invincible.

We drove past small shops selling newspapers that had my face on the front page as I drove up towards the ferry port of Stornoway. That had to be one of the more surreal experiences of my life.

Within hours of leaving the hotel, Inca, my trusty Land Rover and I were sailing away from the Hebrides and into the unknown of Scotland. I didn’t have a plan; all I had was my dog, a credit card and my Land Rover. Although I longed to see my friends and family, I wasn’t ready to return home just yet.

Aimlessly we drove through the Scottish Highlands. That Land Rover brought with it such a freedom. For more than twelve months I had been restricted to Taransay and now I had a wanderlust that was difficult to shake. Apart from the dizzying euphoria of movement, it was also a fear of stopping that overwhelmed me. If I were to stop I wasn’t really sure what would happen or if I would ever get moving again.

We drove until nightfall, when I pulled over to the side of the road and Inca and I curled up in the back of the Land Rover and went to sleep.

And so it was that I disappeared into the Scottish Highlands for a week. It seems strange now, but I don’t remember much about that time. I don’t recall where I went or even where I stayed. My Defender was like a ghost vehicle, winding its way through the mountains.

That Land Rover was my saviour. It offered so much more than just freedom; it also offered me opportunity and hope. And in many ways, this is the essence of the Land Rover spirit.

I kept that blue Land Rover for the best part of four years, but eventually the loan deal came to an end and I had to buy my own car. I’m not sure what came over me, but I bought a Jeep.

A Jeep? I hear you say. How did someone who had spent their life coveting a Land Rover end up with an American Jeep? It gets worse. It was a special Orvis edition pimped out with black leather seats and tinted windows. I am still genuinely puzzled by my decision to get that car. I wasn’t looking for it, it just sort of came into my life at a roundabout near Lord’s cricket ground.

You see, I am an experimenter. I like to experiment and test. I don’t like repeating myself. Perhaps it was a case of having spent four years bouncing and rattling around Britain in a Land Rover Defender that persuaded me to convert … to an American car.

To be fair, it was a cool car. Apart from the tinted windows – I hated those. Believe it or not, I didn’t notice those until after I had bought it. They didn’t stand out in the showroom and it wasn’t until I parked it outside my house and my sister commented on my new Gangsta credentials that I became aware of them.

I drove that Jeep for a year before I had a calling. I had been working on BBC’s Countryfile for several years when I rolled up to a Woad farm one day. ‘I thought you’d be more of a Land Rover man,’ smiled the farmer. It was like seeing the light. ‘But I am a Land Rover man,’ I replied, to the farmer’s confusion.

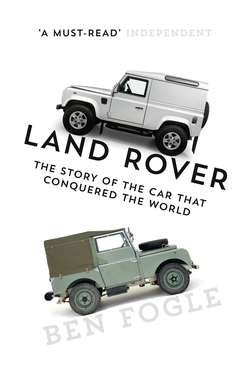

The Jeep was sold and I decided to do the unthinkable, what very few true Land Rover aficionados ever do: I bought a NEW one.

What was I thinking? We all know that buying a brand-new car off the factory line is like chucking money down the drain. The car depreciates as soon as the wheels leave the threshold of the showroom. I don’t think my parents had ever bought a new car. Not a brand-new one. The Fogles had always been rather sensible with money and we all knew that buying a brand-new car was a waste of money, but for some inexplicable reason I found myself in a Land Rover dealership on the A40 in West London putting in an order.

Buying the Land Rover was a big deal. Sure, I had been lucky enough to have cars of my own before, but this was different. I had worked hard for several years and I had saved up some cash. I have never been an extravagant spender (although my wife will probably disagree with that, but in truth it’s more that she is the spendthrift …!). All my life I had dreamed of walking into a showroom and picking out a Land Rover Defender, and here, finally, was my chance to do it. I can remember that day like it was yesterday; the excitement combined with a slight fear of the recklessness and extravagance of buying myself a new car.

The spec was really rather simple. The short wheelbase Defender 90 in silver. I wanted a silver Land Rover. Why silver? I don’t know. Car colour is a strange thing. I included some chequer body plating and three seats in the front. Now this is important – the three seats in the front is part of the Land Rover Defender’s DNA. If we look back to the early Series I and II they all had three seats in the front. It was part of the Land Rover design, but in the latter-day vehicles came the option to add a glove box in the middle.

I am always surprised by the number of Land Rovers that have gone for this configuration. I love the three seats in the front; it is the height of sociability. I remember peering into a McLaren once; the driver sits in the middle while the two passengers sit either side – the industry joke is that they are the seats for the wife and the mistress. With the Land Rover they are more likely to be for the wife and the calf. Next time you are in your car, have a look around at other vehicles and tell me how many have three passengers in the front. There are very few marques that do this – mostly vans. Have a look. Every van will inevitably have three grown men all sitting shoulder to shoulder. Sometimes there is a dog on one of the seats in place of a person, but you get my point.

There is something rather egalitarian about three seats in the front. It takes away the whole hierarchy thing for a start. What is it about the front seat? When I was a child it was like a throne. The front seat was the holy grail of seats and it was always allocated to a strict and unspoken rule of hierarchy, which was usually dictated by age. When Mum and Dad were both in the car there was never any question that they would sit in the front and we children, dogs and parrot would go in the back, but when it came to the school run and only one parent in the car, it became a war zone. ‘Shotgun!’ we would cry as we left the house and raced to the front door. Bickering and arguments would invariably ensue, followed by frosty sulking from the ‘backees’.

The three-seat configuration in the front gives all three passengers the same experience. It is much more inclusive, but of course there is a catch. Have you ever sat in the middle seat of a Land Rover?

A little like everything else about the Defender, it is not the most comfortable experience, indeed, some might call it uncomfortably intimate. The gear stick has to go somewhere, and in the case of the Defender it is located in front of the middle seat. While vans often have the same scenario, they are blessed with slightly more legroom and width. Not so the humble Land Rover, where the long gear stick is positioned between the middle passenger’s legs. Gears three and four are fine, but anything else requires full bodily contact with both gear stick and hand. It helps if you know and feel comfortable with the unfortunate passenger, but where’s the fun in that? I have lost count of the number of people I have taxied around in the middle seat of the Land Rover, their bodies contorted in a kind of twirl in order to avoid all physical contact.

Two months later, my Land Rover was ready. I couldn’t sleep the night before I collected her. I was surprised by my own emotions at the prospect of collecting a new car. She was a thing of beauty, with that unique factory smell that is impossible to replicate once it is lost. I can honestly say I didn’t stop smiling from the moment I stepped foot in that vehicle.

It still amazes me the power of a Land Rover to elicit emotion. Driving suddenly became fun again, and I don’t mean in a ‘pop to the shops as an excuse to get in your new car’ kind of way, but a ‘drive to Cornwall and back in a day’ kind of way. By this point I was working on a number of UK-based shows and I was covering more than 30,000 miles a year. My Silver Bullet went everywhere; although my growing green feelings erred on the side of train travel, I preferred the freedom and anonymity provided by my trusty steed.

Together we covered most of the British Isles. With my beloved Labrador Inca at my side we would drive the length and breadth of the UK to cover rural affairs for Countryfile. A great test of early girlfriends was to see if they could endure a Defender journey to Scotland and back – and I don’t just mean to the border, I mean right up to the Highlands and Islands. I’ll admit it, they were arduous journeys; the shaking and the noise left one feeling slightly frazzled. I must have done that trip a dozen times in a Defender. With nowhere to put a coffee cup or even a bottle of water and too much noise to listen to the radio, they weren’t the easiest journeys, but therein lies the sheer joy of Land Rover travel.

The beauty of the Land Rover lies partly in its characterful imperfections. No matter how noisy or bone-shockingly jarring a journey, I always smiled. She always left me feeling fulfilled. You see, a Land Rover really is so much more than just a vehicle – it becomes an extension of you. You begin to know and understand the nuances and quirks of your car. You can recognise every tiny feature of them. They become something so deeply personal that a criticism of your Land Rover is almost a criticism of you.

It is a well-known fact that the car of choice for the Chelsea mother is a 4×4. Indeed, the characterisation has led to its own term: the Chelsea Tractor. Drive past any school in London’s Kensington and Chelsea between 8am and 9am and you will see an ocean of 4×4s.

Now I will admit that living in Kensington and Chelsea and driving a ubiquitous 4×4 sometimes left me feeling a little guilty. ‘But I use it mostly in the country,’ I would invariably argue when confronted about it by one of my green-conscious friends. Indeed, the Silver Bullet probably saw more of the UK countryside than most Land Rovers, but she still retained an air of urban sophistication that meant she stood out just as much in the countryside. I would often deliberately drive up a couple of verges and through some muddy puddles before arriving at any farms or country fairs. I became conscious of her shiny metallic silver body that jarred against the standard-issue Land Rovers favoured by farmers.

All good things must come to an end, though, and in this case it really was self-inflicted.

Shortly before I rowed the Atlantic in 2005, I had started seeing a beautiful girl, Marina, who would later become my wife. In the early days of our relationship I decided it would be a good idea to drive her down to Devon in the Silver Bullet. It would be the early death knell for the Defender.

Soon after rowing the Atlantic I proposed to Marina. Our lives were amalgamated and Marina gently suggested that the Defender was no longer the most ‘suitable’ family car.

Now, this is far from unique. It is a time-honoured tradition that when a man gains a wife, he loses a car. Some of us fight for both, but one of them usually goes, and in my case I relented, but we wouldn’t lose the marque. We went for a Land Rover Discovery.

Before we took delivery of our black Discovery I had to decide what to do with the Silver Bullet. We didn’t need and couldn’t afford to keep two cars, so the Defender had to go.

I had let go of cars before, of course, but this was different. She really had become a part of me. Together we had been through so much. We had travelled the country together, she had towed my Atlantic rowing boat, we had been ‘papped’ together more times than I can recall (although I do remember the time we were papped on the phone together – me and the car, that is).

If I had had the means and wherewithal to keep her safe somewhere for the future, I would have done it in a flash, but she had to go.

I called some Land Rover dealerships to see if they wanted her and eventually settled on one just outside of Oxford. That final journey was like a funeral cortège. There was an overwhelming sadness as I found myself looking mournfully over her bonnet as we drove up the A40.

It may seem strange to mourn a car, and it had certainly never happened to me before, but there was a sense of finality when I handed over her keys. It was like closing a whole chapter of my life. This was the car I had dreamed of owning, and now that dream was over. It was like splitting up from a girl you still really like.

Now, don’t for a moment blame my wife. She was quite right. The Defender had served me well as a bachelor, but we needed something more suitable for the two of us. We were a partnership, after all, and it was a case of choosing a vehicle that met both our needs.

Marriage is all about compromise. Much is made about being ‘under the thumb’ and forced to make decisions you would never normally have made, but in our case it was about twinning our lives. I know of friends who had the same issues with their sports cars, who similarly mourned the loss of their beloved Porsche or Aston Martin on marriage.

Although it was time for the Defender to go, I resolved that one day I would once again drive the noisiest and most uncomfortable car.

The Discovery was a spaceship by compassion. It was like swapping from a Cessna aircraft to a Learjet. She was brimming with shiny lights, buttons and technology that the Defender could only ever dream of. But here’s the thing: the perfection obliterated the character and charm of her predecessor. I will admit that longer journeys took on a more comfortable edge, but I’ll be honest here, it never felt quite the same as getting into my old Defender. Without the quirks and the imperfections the Discovery became just a tiny bit bland. To use a male dating analogy, it would be like leaving an averagely pretty girl with a great personality for a supermodel. The supermodel is great for a while until you begin to miss character.

It is this that drives the world of the Land Rover aficionado. It is its spirit that we often talk about. The Defender is brimming with character and quirkiness. Each vehicle is different. Each one has its own tale to tell.