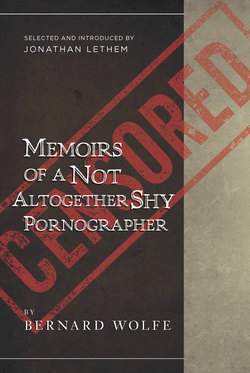

Читать книгу Memoirs of a Not Altogether Shy Pornographer - Bernard Wolfe - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

PREPORN/WHAT’S WHAT

You never know exactly why you got hired for a job You put yourself in the boss’s shoes, you think back to what a fine froth of a boy you must have looked when first you bloomed into his office, babyass cheeks, glassied shoes, neatened nails, cutlery creases in the trousers, morning-mown hair, famously faked work record, panache of a free and independently wealthy soul who’s totally unpressured and going more for inspiration than occupation—you still don’t know.

I did my time in pornography, as this book will tell. In, not for. I didn’t print, illustrate, shoot, exhibit, sell, act in, pose for, or slobber over it, I wrote it, one fat and flamy volume after another. It was far and away the best job I’d ever, by age 24–25, found, and I thought myself smiled on by the gods, if smirkingly, and I prayed it might go on forever. But I never could figure out why they saw me as qualified for this line of work, and actually took me on, those being depression times—the soup lines long, and the competition for all jobs tough.

I went on the payroll well after the Munich Umbrella Caper and in the wake of the Maginot Line Erasure.

My stint in the porno business is not to be rated on the Richter Scale with nation mashings, no. But it could be argued, as here I won’t bother to argue, that all these items are parts of one picture, and maybe the business wouldn’t have been flourishing so, and therefore might not have had an opening for me, if there hadn’t been a lot of Munichs and Maginots happening and in the air.

I was a spic and span lad, all right, toothsomely shaved, barbered, shined and suited. A word about that word “suited.” I was wearing a hand-tailored suit of velvety cashmere, lined with what appeared to be a fabric woven of filamented platinum. When J. Press delivered it to the Yale student who’d had it made to custom, the cost was something like $250, enough in those days to feed a family for months. When it was sold to me by my friend Attilio, the Western Union messenger boy, days after it had been handed to its original owner, judging by its mint condition, the price had come down to $12.50, suggesting that this fellow was more interested in rapid turnover than heavy return.

I never was told how that choice garment came to the Western Union messenger so soon after it arrived at the student’s rooms. I figured it this way. Most likely Attilio had delivered a telegram to the dormitories. Most likely it contained good news, maybe word from a girl up in Vassar that she would be coming to the thé dansant or that she was back in the flow of things after all and not to worry. The student had probably wanted to give my friend a nice tip. There probably wasn’t any loose change around. But J. Press cashmere suits? These were all over the place. Attilio, by the way, was always getting tips of suits, camel’s-hair coats, wristwatches and bags of golf clubs from the Yale students. He must have brought them lots of cheerful bulletins from Vassar.

So for Pierson Quadrangle I was smashingly well suited. This tells us nothing about why the porno people took one look at me and decided I was similarly suited for them. Porno is not the most nepotistical power pyramid around when it needs new blood, but neither does it bend over backward to make openings for rank beginners. Some ranknesses it doesn’t have use for. A few.

• • •

I refuse to believe that luck was the whole or even the main story. I think it was a matter of talent too. I think I had a thousand rare gifts tailormade (like the cashmere suit for the Yale student) for this kind of work and those in charge were smart enough to spot them. What puzzles me is how.

Whether or not I was a writer I could do the things that writers do and that the porno people wanted done. I had the looked-for talents, if not the vocation. The thing that shook me was that my employers could see them when they were nowhere on display.

I thought for a long time they were seeing things and trying to suck me into their hallucination. They did convince me, finally. They paid me good money for my products and everybody knows that money talks louder than words, loud enough sometimes to drown out all other sounds; including those of your own doubts.

A voyage of self-discovery. Shit to the moon and back, we’d better find a way to talk to each other for a change, that isn’t language that can get some human facts across it’s writing. The sort that people who write do more than writers.

Say I entered into the porno world shapeless, nameless, a blob, a nobody, and came out of it wearing a badge of office that wouldn’t rust too fast and could be accepted without giggle by the outside world and, more importantly, me. It wasn’t a perilous sailing on the high inner seas, or a long and parched staggering across the baking deserts of alienation to the oasis of healed identity, or a mountain climber’s inch-by-inch crawl up the sheer cliffs of inauthenticity to the sunny if austere peaks of inner-direction. No, sir, it didn’t have any of the high-rise drama found so regularly in poets’ trips and so rarely in real-life ones, it can’t be called anything so dramatic as discovery if that means some moment of rosy epiphany dispatched from stage-wise heavens with a Jack Lemmon sense of timing, say, rather, it was a game of slow-motion tag, that’s closer. Not all the way there, but close enough. A game I came out of with an identification tag on me that was useful and even comforting.

Not all labels are to be sneered at. The ones that are transparent so they can’t be used as masks, and give real names instead of aliases and real addresses you can be sent home to in case you’re hit by a truck or get clouded by amnesia, they can do something for you. Get you back where you’re known and belong, should you stray. Jog your memory as to your rank and serial number if you get a little hazy, as everybody does at times.

Nobody’s ever going to prove himself a writer by doing porno for the commercial market but it’s a hell of a good place to go to find out in a hurry if you can write. Some people take correspondence-school exams, some enter limerick contests, some keep composing letters to the editor—I tried my wings at porno, as will unfold here, and wump, I was airborne. If I was lucky to come across the porno barons in their time of need, they had an equally charmed moment, were really on the sunny side of the hedge, the day they found me needy and therefore available to them.

My hat’s off to those sharp-eyed people for seeing my stashed merits and drawing my attention to them.

The Eastern Seaboard was overrun with people not so sharp-eyed. Twentieth-Century-Fox said no, absolutely not, neither now nor in this lifetime, to my request for a post in their New York publicity office. Yale University Press, while granting that the subject might with profit be looked into sometime during the next hundred years by somebody who knew something about it, had turned down my project for a study of the tendency in even the most Jacobin of revolutions to lurch on to Thermidor. Over and over Time-Life had informed me that they had no openings I could fill and did not see a time in the next decades when they might have a space that odd-shaped.

That bothered me, since a lot of Yale graduates had the impression that the strongest qualification you could have for a staff job at Time-Life, next to writing sentences backward, was to be a Yale graduate, and I was. (I could also write sentences backward.) I was, of course, also a Jew (more accurately, was called that by others who seemed fairly sure of themselves), the son of a factory worker, and for some years a Trotskyite, moreover a recent member of Trotsky’s household staff, traits which very few Yale graduates could boast, especially in that rich mixture, especially those who made their way to Time-Life. If Henry Luce’s proconsuls failed to see the virtues in me that the porno people later spotted and bid for, the burden of explanation is on them, not me.

They didn’t need me and were determined not to make room for me on all the magazines and newspapers in the Greater New York Metropolitan Area. They’d forged a policy of keeping me at a safe distance from all the Madison Avenue ad agencies, all the radio stations, small independents as well as big network affiliates. When I answered classified ads for trade papers and house organs, ghosting agencies and vanity presses, for jobs composing mail-order brochures, how-to-do manuals, throwaways, comic books, seed catalogues, they scrupulously did not let me hear from them.

There was a terrible depression on, sure, but even national calamity didn’t explain why all of American industry, even, as you’ll see in a minute, the sectors that made and sold things other than words, had gotten together to lock one man out. Say they did have grounds for suspicion when a Jew, a Yale graduate, a son of the proletariat and a recent Trotsky boarder showed up on their doorsteps all in one person. They still had no right to assume so automatically that the one reason a man so configurated would want to get on their premises was to blow them up—that’s stereotyped thinking and not in the American spirit of judging a man by what he can do rather than by what he came out of.

• • •

Most of the economy was still creaking along but one branch of it, war industry, was beginning to buzz. I went to a Manhattan employment agency that specialized in factory work. They said military-hardware plants were looking for technical writers. Was that in or around my line? I informed them that I’d taken a course in engineering drafting at Yale, that the blueprint hadn’t been drawn that I couldn’t read, that if they wanted the plain facts blueprints were my favorite reading matter.

Next morning I was sitting in the personnel office of a giant electronics firm over in New Jersey, so close to the Secaucus pig farms that you had to keep blowing your nose so they couldn’t tell you were holding it.

The manager gave me a blueprint. He wondered if I’d be good enough to point out what I recall as the intermeshing backup reverse-feed alternate-bypass switch-trip voltage-trap breaker circuit. Partial to curves of all types, I put my finger fast on an ingratiating cluster of chicken tracks in a circular pattern.

No, he said, this element wasn’t part of the wiring system. Then I got the whole truth: it didn’t have anything to do with the internals of this piece of apparatus, in fact what I was pointing to was one of the ball-shaped feet the console rested on, the right front one just this side of the tuning dial. The chicken tracks, I now saw, were just the draftsman’s indication of the roughened texture given to the foot’s plastic surface for a better purchase.

The reference to tuning interested me. What did this dial tune, I asked, a radio set?

Not exactly, he said, this was a control unit for the sonar sounding system for a submarine, useful in locating other subs and traveling torpedoes it would be good to know about. Besides, if I didn’t mind his mentioning it, what I now had my finger on wasn’t the tuning dial, it was the manufacturer’s trademark embossed on the casing.

Letdown, though I tried not to show it. For a quick minute I’d had the happy thought that I might be getting into the radio end of the up-and-coming communications industry, if only in the manufacture of consoles.

The manager asked if at some time in my early life I might have experienced a trauma with liquids, say a swimming accident that left me leery of waters over my head or any reminder of them. He thought this might be a possibility because the suggestion of deep waters seemed to panic me to the point of incoherence, not a good state of mind in which to study electronic circuits for sub-surface vessels nine to five. He wondered if a man with my emotional setup wouldn’t have a happier life writing assembly and operating manuals for a talking-doll factory, say, or the people who make Lionel trains.

I was in his palled eyes every inch a writer, that highly specialized type of writer who can’t read, and he wanted every inch ejected from his office so it could go back to smelling no worse than Secaucus.

Once, only once, I scared up some action from the help-wanteds.

A publisher was looking for a bright young man wanting to go places, good starting salary, unlimited opportunity, fast advancement. Said bright young man had to have a good plot mind and a knack for snappy dialogue. I knew I had a nimble plot mind, I’d been plotting for years to keep eating and so far wasn’t losing weight. I had proof of my knack for snappy dialogue in the number of times I’d been removed from rooms by other people who countered with their knack for it. Anyhow, I got off a letter full of unrestrained enthusiasm for myself. A man with a voice to dislocate seismographs called to invite me down for an interview.

The address was on the Lower East Side, just off Delancey Street. It turned out to be a fifth-floor loft that had to have seen better days, otherwise it would have been condemned by the building inspectors the day the roof went on. This I estimated was around the time Peter Stuyvesant was being fitted for his fourth or fifth pegleg. Possibly Peter was one of the building inspectors. The shredding wooden floor had a lot of holes that looked like knotholes but could have been pegleg perforations. The room was bare and dusty and smelled of printer’s ink. From another one to the rear came a labored chinking sound, the sort small printing presses make.

The man who greeted me had no part that was not alarmingly pendulant. All his tissues seemed to have been systematically displaced downward, as in a melt suddenly interrupted, giving the queer impression that forehead was where nose should be, nose where lips, wrists where fingertips, and so on—a landslide of a man. His outstanding feature was his nose, I mean it stood out as though it was ready to leave home and had already taken the first step, yet what I remember most is the lips, they were really in love, constantly kissing and moving apart like a fish’s.

There was something fishy about this man all around; if you looked through the window of the big aquarium at Marineland and spotted him lazing along with the carp and manta rays you’d have thought he was at home, except for the matching argyle sweater and socks. I guess he wanted something in him to match, his eyes certainly didn’t, one was dramatically blackened. Our conversation went like this:

“How’re you at dialogue, kid?”

“I use it all the time.”

“We’ll start again. How are you at dialogue?”

“I keep up my end.”

“Suppose you had to keep up both ends.”

“I’d keep them up and play them both against the middle and have one hand free to write some dialogue for you. That’s a sample.”

“That’s a sample. Tell you what to do with that sample. You go make up some more, then take that one and chew it and swallow it before the cops get their hands on it. You’ll have ptomaine for a few days but that’s better than the electric chair. You think you could tell a whole quick-moving story in dialogue, say 15, 20 lines at the most?”

“If spoken by people with 15 or 20 things to say, sure.”

“I see you’re a wiseass but I’ll tell you, we could have some use for a wiseass. We specialize in fumy stuff around here and maybe with a lot of coaching a hotshot joker like you could come up with a tickle line or two. You acquainted with the Tijuana Bibles?”

“I’ve heard a lot goes on in those border towns but not much that calls for religious reference works.”

“These bibles they don’t use, they make, and fast as they come off the presses they go over the border.”

“Oh. You’re in bibles on the manufacturing end. Well, I could be very useful to you there, I’m not familiar with the Tijuana Bibles but I’ve read a lot of others and if you want some more bibles written I’m your man. I’ve made a study of how to get in the right frame of mind to write messianic copy, you think yourself into the position of the Pied Piper, say, or a white hunter, or the soldier who walks point in a patrol, any frontrunner type, then you think a halo around your haircut and start looking upward more than sideways or over your shoulder, and pretty soon some real leadership prose starts—”

“Put the stopper in, kid, you could sprain your tonsils. I’ll explain it to you, Tijuana Bible’s a nickname for a certain type funnies, like so.”

The thing he took from his desk drawer to pass across was a comic book, in full color, on paper that upped five or six grades could have been used for Kleenex. All the characters, I saw as I leafed through, were known American ones, but their words as captured in the balloons oven their heads were all in Spanish, more, they’d all lost their clothes, every last button and string, and were heel-kickingly happy about it, judging from the shrapnel they all were generating—ripples, shimmers, shooting stars, pows, bams and exclamation points, judging further from the interpersonal antics they were engaged in with all portions of their bared anatomies. These carefree cutups didn’t have any problem relating to others, they were relating in every way the epidermis allows, variously coupling, tripleting, communing, nosing, mouthing, fingering, backbending, splitting, three-decker-sandwiching. Moon Mullins was ringmaster for a tightly interwoven daisy chain that Dagwood was working hard to unravel. (Thanatos forever trying to undo Eros’s best work, where will it end.) Mickey Mouse had had a knockdown fight with Minnie Mouse. He’d decided to cut all troublemaking females out of his life and go it on his own. Just now he was exploring the insertive possibilities in a slab of Swiss cheese while over on the far side, unknown to him, Minnie was energetically reaping the benefits of his probes. The Katzenjammer Kids were here revealing themselves as powerhouse-jammers. The object of their ramrod affections was none other than Little Orphan Annie. Aided and abetted by a slavering Daddy Warbucks, they were using that diminutive Brillo-haired lady as a human pincushion, entering her at every passageway as though to make the point, long before Sartre, about there being no exits. I took no pleasure in what was being done to that little slip of a girl though I’d always thought she was too big for her britches (now missing) and needed to be taken down a few pegs for her protofascist leanings.

“—by the carload down there,” the man was saying. “The art work’s right on the nose, sure, they draw fine, but where they fall down is with the continuity, see, the talk give and take, their dialogue writers don’t cut the mustard—”

“I’ve often wondered about that.”

“About what?”

“Why any mustard should be cut. Most mustard, if you cut it it’s back in one piece the second you take your knife out, so I don’t—”

“You’re a smartski. You’re a button buster, no doubt about it. All right, here’s where a weisenheimer like you could come in. We take over the drawings but leave the Spanishy crap out of the balloons and fill in our own lines in English. We need people to write the lines. Bright young fellows who can turn a phrase without it saying ouch. We can pay for the words pretty good because we get all this art work for free, we lift it from these thieving Mexes so we come out way ahead on the graphics end. You by any chance read Spanish, kid?”

It happened I did, and said so. I’d taken Spanish in high school and applied myself a lot more than I did later in college to engineering drafting. He handed me another comic book, this one with the Spanish balloons intact.

“Here you got a Tijuana original we’re right now in process of knocking off. Study the human situation, the dramatic setup, then read the dogass words those chumps put in and you’ll see our problem.” I studied the human situation. This was a full-page drawing he’d opened the book to, one featuring Popeye the Sailor Man and his girlfriend Olive Oil. They, too, had separated themselves from their clothes and were respectively, balls naked and pudendum naked. (Will Wimlib’s study of the sexism permeating our language be complete without a close look into the circumstance that we have all sorts of lively terms for male nudity but none, none at all, for female?) Popeye had insinuated himself into Olive Oil from the rear. His footloose organ was exiting from her mouth to the tune of maybe two feet worth. She looked slack-jawed and crosseyed, understandably; he was puffing absorbedly on his corncob. The exchange they were having went:

POPEYE: Don’t you worry about me running short, little cactus flower, in case you need a few more feet I got plenty to spare, I just ate two whole cans of spinach.

OLIVE OYL: You might run through another yard or so if it’s not too much trouble, my heart, that should be enough to mop the floor with where you spilled all that spinach juice, you’re sure a sloppy eater.

I thought that was damn good writing, if a little wordy, considering the limited possibilities. The text was not prurient and I found it to have redeeming social value. It didn’t capitalize in an obvious way on the setup. It didn’t try to put any icing on the already rich cake. It showed an original turn of mind, a free-wheeling imagination ready to work against the given materials, which takes courage. I couldn’t see how these lines could be improved on but the man for some reason was not satisfied.

“Well, sonny boy, let’s see what you can do,” he now said. “Take this page. As you see it’s a proof of the same drawing but with the balloons blank. O.K., you fill them in. Give us some lines that grow out of this interesting situation and sort of round out the visual picture, tell some kind of a little story. Here’s a pencil. Don’t rush, I got all afternoon, we’d rather have it right than Tuesday.”

My plot mind had retired to the old soldier’s home. My knack for snappy dialogue was out on some street-corner selling apples. After several false starts this was the best I could think of to write in those balloons:

POPEYE: Where do you stand on a third term for Franklin D. Roosevelt?

OLIVE OYL: Is that with one “o” or two, I never seem to remember.

The man studied my effort. He studied it for quite some time. He looked out the window and whistled soundlessly, which is said to be an ominous sign. His one black eye appeared to be getting blacker.

“All right,” he said. “I’m counting to five. I’d count to one but I’m not primarily a murderer. When I get to five should you not have your smart ass halfway down the stairs it’ll be leaving by this window—”

I was in rapid transit. I was never to know just who had given him that black eye but there were all sorts of possibilities, any one of the Tijuana publishers he stole from, any one of the American cartoonists they stole from, any of the bright young men he gave his balloon-inflating tests to, the NAM (for the way he maligned a pillar-of-the-community capitalist like Daddy Warbucks), the American CP (for his demeaning of an honest proletarian like Popeye), come to think of it, even Little Orphan Annie, for assorted indignities.

That man—when I picture him today I see him with argyle hair, too—did not know his own business. He was of the opinion that I lacked the golden touch for porno. Wait till you hear.

Why did I keep going after jobs in the word industry? Well, what are you going to do when non-word industry up and down the land keeps slamming its doors in your face?

One sector of it, the war plants (they were beginning to acquire a more amiable face by being called defense plants) was, if I can put it this way, going great guns. But every time I showed up they had to exert themselves to keep from leveling all those guns at me. My plight had something to do with my being a college graduate. That biographical detail was everywhere, and especially by people in hiring positions, taken to be an ID, not just a clue as to where I’d spent the four years after high school.

They were good Manicheans, those personnel people, last-ditch dualists; where they saw any trace of psyche they wouldn’t allow for the merest soupçon of soma. Assuming that college had pumped my head too full, they also took it for granted that my body had somehow gotten lost in the cerebral shuffle and dropped off, and bodies were the items in short supply in their booming defense plants, and over-bred heads they were making short shrift (an organic-food variety of shortbread) of. Language was where I had to get some occupational footing because language was where I was dumped by the industrial body-snatchers.

All the things I’ve just said are true but not the truth. There had been signs along the way that words and I were a good deal more than kissing cousins, were, indeed, as Damon to Pythias, Sears to Roebuck.

Item. From any number of people who were around at the time, presumably with hands pressed to ears, had come the report that I was speaking whole sentences, loudly and firmly, before my first birthday. I’ll save my main comment on this noisy prodigality until later. Here I’ll record the one thought that at that time, somewhere along in 1916, I probably didn’t have much to say, just the urge to say it well, fully, emphatically—some well-chosen words, no doubt, as to how badly things were already going, and how much worse they could be expected to get, and how this was in no way my doing, indeed went counter to all my plans and objectives, and how the swarms of people out there on all sides whose doing this transparently was were all bobbing and weaving in the most disgusting manner to dodge the responsibility, and how they’d probably be getting away with their who-me act if I hadn’t been endowed with the set of tonsils to denounce them and itemize their assorted shoddinesses for the world to shudder at. A few such marginalia from a beginner with lynxy eyes and none of that existential passivity toward the given, the latest form of do-nothing stoicism.

Item. An English teacher in New Haven’s Hillhouse High assigned us to write a page or two of description with a warning to avoid trite subjects like trees, snowflakes, flowers, bunny rabbits and sunsets. She seemed to take a particularly dim view of sunsets. I sat down and composed a piece of surging, singing prose about a nightfall to end all nightfalls, a lyrical accolade which was in one part a forerunner of today’s psychedelic light shows, in another an anticipation of Hiroshima.

I was determined, you see, to get it established that for such as me no subject was trite, my flashing prose would make the most overdone matters all shiny and new. Somewhere in France at just about that time, and unknown to me, James Joyce was recording his immortal line, “I can do anything I want with words.” In this early essay, I see now, I was making the same statement.

My aim, it has to be faced, was not altogether literary. This teacher, by name Nora, was very young, very blond, and luscious, which New England teachers of English at that time were conspicuously not. If I thought I could do anything with words one of the things I most meant to do was make her aware of my presence, pay attention. I thought it worked but I wasn’t sure. Nora did give my paper an “A.” She also wrote in the margin, “If we have more sunsets like this, sunrises are going to go out of business.”

Item. As a result of such virtuosity I became president of the Hillhouse Writers Club, then editor of the class book and the literary annual. I can’t remember much about the first honor except that I somehow made use of it to get excused from gym, maybe on the grounds that in born writers the head has so overshadowed and sapped the body as to render it unfit for physical exertions. (A lesson about the literary life I’ve never forgotten: it can, if you work it right, get you exempted from lifting things, including yourself.)

Unwilling to compromise on quality, I undertook to fill the pages of the literary magazine with the best prose around, my own. My first appearances in print were in this annual. One item was an essay entitled “On Being Lazy,” a treatise elaborating on all the delights of not working, designed, clearly, to annoy the many Yankee partisans of the work ethic who presided over the school. Another contribution was a short story about a gifted young student who has to work nights in a factory. He’s in a state of exhaustion. One night he sinks down on a comfortable leather belt to take a catnap, whereupon the belt is somehow activated to feed him into a grinding machine. The factory was pretty much modeled after the one my father worked in, and the high-potential young student had a variety of things in common with me, indicating, I suppose, how far back my paranoia about American industrialization took hold.

This story was by all standards a piece of proletarian literature, though the term had not yet come into currency. Two short years later writers by the hundreds had shed their Brooks Brothers gabardines for blue denim work shirts and the Proletarian Novel was swamping the American literary scene. Nowhere, however, in that massive body of workingclass literature will you find one word acknowledging the highschool junior who sparked the movement. But that’s always the fate of the frontrunner. No prophet is so scorned in his own country as the one whose pioneering work is taken over lock, stock and barrel by his plagiaristic countrymen.

I contented myself with the knowledge that of the 100 or so prolecult novels that flooded the bookstalls few came up to the literary level of my early effort, and practically none added anything to my innocent-victim thematization of the contest between nice young lads and carnivorous old free-enterprise machines.

(That wasn’t meant cynically. I’m still of the opinion that our means of production are really consumers, savage meat-eaters, even, I would now add, when the social relations of production have been drastically changed—in form, anyhow. It has dawned on me, though, that young fellows who try to catch 40 winks on a shaft-driven transmission belt, no matter how worthy and no matter how tired, are, to put it mildly, mastication-prone.)

Item. There was a national essay contest for high school seniors. I entered it and won it. My subject, since I was oriented toward science to get away from letters, rather, from the kinds of people who usually teach letters, was, the future of soil-conditioners in American farming. Or, “Whither Fertilizers?” Something in that line. I made up a joke about this contest—maybe you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear but you sure can get together a big pile of horseshit and come up with a prizewinning essay.

I was breathing hard in anticipation of some cold, hard cash. What they handed me was a leather-bound commemorative volume honoring a dean at Harvard who’d been helpful to several generations of incipient writers when they were undergraduates, among them John Dos Passos. The dean’s name was Riggs, or Briggs, or Griggs. I’m pretty sure it wasn’t Tetrazzini. I’ve never read that book. Not that I had anything against this dean—what put me off was that they should give me payment in kind, instead of the kind payment of money.

It simply did not make sense, in or out of the Great Depression, to reward words with words. This seemed to imply that the most important thing for an incipient writer to do was read, not eat. That committee on awards turned its collective back on the strong possibility that neither reading nor writing was going to be feasible for me if I suffered from malnutrition, and in those days an awful lot of people, including writers both incipient and well-launched, were doing just that.

I don’t know if that copy of the commemorative volume is still around. Maybe it’s buried in a carton in my brother’s cellar outside New Haven, I haven’t seen it in decades. I rather wish I had it now, I’d like to read about Dean Riggs, or Briggs. I understand he was very nice to John Dos Passos. For some years I’ve been trying to be nice to incipient writers at UCLA and I’d be interested to see how our techniques compare.

Item. So we can say that at 15 I was by any definition an incipient, as well as malnourished, writer. Further proof came in my first year at Yale when I won some sort of freshman essay contest. My subject this time was the development of the esthetic of realism, which my survey traced, hastily and in big jumps, from the early cave drawings to Norman Rockwell and Raymond Chandler.

This time, too, I got not a penny, just a voucher entitling me to $25 worth of books at Whitlock’s Book Store. I pleaded with the people at Whitlock’s to convert that useless piece of paper to negotiable currency but those incorruptible Yankees—whose enthusiasm for steady habits (Connecticut had way back nicknamed itself “The Land of Steady Habits”) did not seem to extend to eating—wouldn’t hear of it. I finally took my payment in Modern Library novels, sat up several nights devouring them two or three at a time, there being little else around to devour, then sold them for whatever I could get. With the proceeds I bought a meal ticket at the Greek’s on Chapel Street, where they offered a marvelous thick and crusty breaded veal cutlet drowned in tomato sauce with a heap of spaghetti and two fat buttered rolls for 35 cents.

For once, however devious the operation, I’d managed to convert award-winning words into food, and you will not mistake my meaning when I say it whetted my appetite.

Item. Words finally did bring in some moneys at college. With my good friend Johnny Dorsey I started a ghosting agency for people like football players who had no time to write essays and term papers and who in any case had probably so sapped their heads by overnourishing their bodies that they couldn’t write anything. (If the Manicheans have at times kept me from employment, at other times they’ve made profitable work for me.) We charged four dollars a page if the client was satisfied to squeak by, but hiked the price to six if he wanted a guaranteed “B” or better.

I must say that when we gave a grade guarantee we stood behind our product and we never missed. This can be interpreted in a couple of ways. It might mean that we were incredibly talented writers. It may, on the other hand, suggest that Johnny Dorsey and I knew a lot of the young reading assistants who graded papers for the professors, were alert to their crochets, and got good at assessing their tastes. For a couple of years there Johnny and I ate well at the Greek’s, and any number of varsity members did their double-shift wingbacks at the Yale Bowl with an easy mind.

Item. After some pointless months in the Yale Graduate School I quit to take a teaching job in a school for women trade unionists which operated on the Bryn Mawr campus during the summers. Here I reached new heights of eloquence, though of the oral rather than written order, particularly when I addressed the noontime assembly on current happenings around the world.

One noon I lectured forcefully as to why the political tensions now mounting in Paris would have to explode with a military bid for power by the labor-hating fascists in the Croix de Feu. Two days after I made my categorical prediction there was a fascist uprising, Francisco Franco’s in Spain. I quickly appeared before the assembly again to announce that my analysis of the class struggle in Europe had been absolutely right but that I’d gotten the country wrong, that was all. I overwhelmed these girls the first time and I overwhelmed them equally the second without shifting any essential gears.

Right after that I came down with a bad case of gastric poisoning and had to spend several days in the campus infirmary. Nobody visited me on my bed of pain to crow over what happens when a man has to eat his words (I thought I’d avoided that rather neatly) but oh, how my stomach hurt.

Item. After Bryn Mawr I hung around New York for a time producing for the Trotskyite publications (The Militant and The New International) words covering the Spanish Civil War, the one I’d misplaced geographically, plus book reviews and an article or two. I discovered that the best way to report any overseas war is to sit in a Greenwich Village room and redo the dispatches of the New York Times correspondents who are required by their task-master bosses to make personal appearances at the fronts. (The approach I picked up in this period was to stand me in good stead during World War II, in which I avoided personal appearances on a wide variety of fronts.) The technique is simple, you keep the facts cabled home by the front-line reporters, since you don’t have any of your own to substitute for them, and just correct their blurred vision with Bolshevik-Leninist bifocals.

One piece I did for The New International was an exhaustive study of the theoretical errors vitiating all schools of criminology past and present. The thematic burden of this analysis was that the criminal in capitalist society is simply a revolutionary who through an oversight has neglected to join a Marxist party and coordinate his rebelliousness with other people’s. It beats me how I happened to wander into the field of crime and its causes. It could be that more of the Puritan work ethic had seeped into my head than I realized and prolonged unemployment was making me feel like a criminal. Certainly writing articles on the unconscious politics of footpads and second-story men wasn’t giving me any sense of gainful employment, whereas the criminal welcomes any opportunity to present himself as a politician—it’s a promotion, though a slight one.

(This is in no way to make light of the current politicalization of our prison populations. That is progress all around. But if we want to keep our bearings, particularly those of us on the left, we’d better see the difference between prisoners who take to politics in a mighty striving for mind expansion and those—their numbers may not be negligible—who reach for politics as a handy, because fashionable, mask.)

I feel now that this analysis done in 1938 was defective in key respects. It seems to give less than the full story about a number of disorderly and impatient types, from the Boston Strangler to Charles Manson. I’m relieved, in retrospect, that my article did not bring a rush of recruits to the Socialist Workers Party from the chronic lawbreaking strata—if the Stranglers and Mansons ever decide to flock to a leftwing movement their comrades will have to put on bulletproof vests and hire bodyguards to see them home from meetings.

My real point is that the words I was turning out in this period, if totally wrong, were uniformly effective. My comrades thanked me many times for setting them straight on both the Spanish Civil War (which they never knew I had located in France) and the blind alleys all criminologists but me had gotten themselves into.

Item. In the course of time I was invited to join Trotsky’s small secretarial and household staff in Mexico, where he’d received asylum after being expelled from Norway by Trygve Lie’s whimsically and skittishly socialist government. This was another nice, if not in any way remunerative, recognition of my dexterity with words—they needed somebody who knew English, could translate documents from French and German, prepare news releases and in general handle the press. It was clear to me that Albie Booth (star quarterback and captain of the Yale football team when I was in school) would not have qualified for this job, so it looked like my exemptions from gym had not been in vain. I won’t dwell on my literary activities during this year in Mexico because, although my output was high, its form was minor: mostly postcards.

Item. When I got back from Mexico I was taken on by the Connecticut WPA Writers Project to head a research and writing team that was said to be preparing an ethnic study of the peoples of Connecticut for ultimate publication by the Yale University Press. More about this job later. I’ll just point out here that I would never have gotten it if I hadn’t appeared to the WPA bureaucrats as a writer, at least somebody who could write, and, further, if a good friend of mine hadn’t happened to be doing the hiring. This appointment would have seemed sure proof of my literary calling if I hadn’t observed, right after reporting for work, that Albie Booth could just as well have wangled the job and passed unnoticed no matter how much writing he didn’t do, all the people present being too drunk or too hung-over to check on anything but the Alka-Seltzer.

I elected to do my main research in Yale’s Sterling Library, where if the ethnic components of the Connecticut population were not highly visible the furniture was at least softly upholstered. I spent most of those 18 months sleeping in the splendid sofas of the Linonia & Brothers Reading Room. It was in this vaulted chamber, soothingly reminiscent of the Union League Club, that one day I picked up an avantgarde magazine from Paris and read Joyce’s haunting sentence, “I can do anything I want with words.”

My reaction to that chesty line should be recorded. I thought, here I am, ready, willing and able to do anything anybody wants with my words so long as they’ll pay modestly for them . . . dying to get some words out tailored to the needs and interests of some market, any market at all . . . my full literary equipment is there on the block, and they’re all too busy reaching for the Alka-Seltzer to take me up on it, make a bid, draw some guidelines, notice me at all.

You might say that under the circumstances, since I was drawing a paycheck every week—nothing great but enough to eat on—I might have used my great gobs of free time to do something I wanted with my unemployed words. But that was just the trouble. There was nothing I wanted to do with them, nothing I dared to do, except put them up for sale and lament the absence of buyers.

One more item, this going back to the Mexican days, and you’ll have the background picture.

It wasn’t a soft life we had in that broken-down villa in Coyoacán, then a backwash village outside Mexico City. It was, all in all, a radical departure from the sculpted panels and puffy pillows of Linonia & Brothers. We lived in a one-story house built around the thee sides of a patio, all of the single-file rooms opening on the internal garden. There was no heating system. When the panes of the French doors got broken they didn’t get fixed. It turns cold nights on the Mexico City plateau, up 7,500 feet. You look to the snow peaks of Popocatepetl and you feel that snow in your bones, in your teeth.

We were often up nights in that drafty, unheated place, feeling the Popo snows. We had to be. In addition to the day’s chores of paper work and seeing to security we, the members of the secretariat, kept a rotating guard shift through the night. There were three of us, a Frenchman, a Czech, and myself. That meant we split the night into three watches, early, middle, and late. That meant that every third night I could expect to be up through the most miserable hours from midnight to almost dawn, huddled in a soldier’s ratty fur wraparound left over from Red Army days, blowing on my fingers, trying not to let the cold blow my mind.

Lots of nights I sat in the dining room at the 20-foot-long lemon-yellow wooden table that we used at one end for eating, at the other for our typewriters and papers, taking apart the Luger I’d been issued, then putting it together. I had no strong interest in the insides of a gun, though I’d never examined them closely before. The idea was to have some project, focus the head, keep busy. The cold wouldn’t go away but it could, with strategy, he banished for periods to the outskirts of mind. I had to use my fingers somehow. I couldn’t think of anything to do with them at the typewriter, having written all my postcards hours before and having no nobler literary projects in mind. I broke that Luger down till it couldn’t be reduced any further except with an acetylene torch. Night after night I did this, getting it all apart, then getting it all together.

Once, very late, the Old Man came through the dining room on his way to the bathroom, and saw me with parts of the gun in my hands and more parts spread on the table. He was always alert to how the young people around him behaved with weapons, afraid that their tendencies to kid around and show off might make them careless.

His hands-off style wouldn’t allow him any tone of chiding or lecture. He just said quietly and seriously, “You know, in the Revolution we lost more people than the enemy could claim credit for. Many young comrades killed themselves with their own guns and suicide was very far from their minds.”

I said, “You don’t have to worry about me, L.D., I always take the clip out and make sure the chamber’s empty, there’s no danger here.”

I couldn’t detail for him all the ways in which there was no danger. Minutes before he’d appeared, just as I was beginning to fit the barrel back into its housing, there’d been a whiffing noise and I’d watched some spring from the firing mechanism fly out the French doors. I was vague as to the spring’s location in the innards of the gun and in the dark as to its function. But wherever it operated and whatever it did, I knew it was important. Just before the Old Man came in I’d proved to my satisfaction that the gun would not fire without this obscure coil. The perfect gun, you might say, for Russian roulette.

The Luger was never to fire again. That night, and many cold nights after that, I spent hours on my hands and knees around the cactus and pieces of Aztec statuary in the patio, looking for the spring. It was nowhere to be found.

I really don’t want to talk about the state of our weaponry in Coyoacán. I’m simply drawing your attention to the fact that in that cold room on those cold nights I had to get my hands working at something. Since guns wouldn’t do it for me indefinitely, sooner or later I had to face the fact that there was another piece of apparatus present whose springs wouldn’t take flight so readily—a typewriter. And so began some writing on my nights of vigil because there was nothing else available to keep me from climbing the walls, which were black with tarantulas.

It was hard to get started. If in those days there was any relationship between me and words it was one in which we warily circled each other, unable to come together, unable to break it off and go our separate ways. As a result I was a little stiff with the writers who came visiting at our house. There were many—Jim Farrell, who was later my good and helpful friend, Michael Blankfort (later to be president of the Hollywood Writers’ Guild, currently my neighbor in the Beverly Hills rat trap where I have my office, and am writing these notes), Herb Solow and Johnny Macdonald (both of whom wound up as editors on Fortune), Suzanne LaFollette, Benjamin Stolberg, Charles Rumford Walker, on and on. I felt a bit guilty to be presented to them as someone with a political identity, guiltier yet because my deepest urges were toward writing and I couldn’t say a word about them. What was there to say? That I read like a demon? That I knew a shitpile of novels? What does such information communicate about a man except that he’s an insomniac, and pretty anti-social to boot?

There was my problem. The fancy name for it these days is identity crisis—in those simpler times all we had to say about this shaky condition was, Shit or get off the pot. I had to appear as, and go through the motions of, a politico, at which I really wasn’t very good, mainly I just repeated other people’s phrases. I had to keep under cover those appetites and curiosities about which I could really hold forth because that’s all I’d ever done about them, hold forth, not work with or build on. As a result I was invisible. When later my good friend Ralph Ellison brought out his novel Invisible Man I knew exactly what he was talking about, though my own long bout with invisibility had taken place in a nonracial context.

But, you know, writers were in a certain sense the niggers of the left movements. These days all groups that feel set upon like to apply to themselves the labels of the oppressed black—students talk about being treated like niggers, as being the Harlem of the young, and so on. Writers had plenty of reason to see themselves that way in revolutionary circles. They were looked down upon as cafeteria intellectuals, parlor activists, undisciplined and irresponsible bohemians. They were defined as incorrigibly petty-bourgeois, constantly slapped in the face with their non-prolism. In all respects that counted they were held to be inferior people who if they had any loyalty to the cause of social overhauling at all would allow their names and public weights to be used without ever presuming to question the hallowed fulltime politicos who used them. This anti-egghead arrogance was most vicious in Stalinist circles but it was by no means unknown among certain Trotskyites.

For example. Jim Cannon was the titular head of the tiny Trotskyite movement in those days. He had plenty of reason to feel grateful to Suzanne LaFollette. Suzanne was not in any sense a Trotskyite but she’d been sufficiently repulsed by the Moscow Trials to take an energetic lead in organizing what became known as the John Dewey Commission of Inquiry into the Moscow Trials. That Commission had spent weeks interrogating Trotsky in Coyoacán. (One of the main reasons I’d been sent to Mexico was to help prepare documents for these hearings.) Then it had returned to New York to prepare its two-volume report, which exonerated Trotsky from all charges made against him and established the Trials as complete judicial frame-ups. This was an enormous service to Trotsky and his followers, one they could never have performed for themselves. I had come back to New York to help Suzanne get the documents and verbatim transcripts in order for the publishers, Harpers.

Although spending most of my time with Suzanne, once in a while I ran into Jim Cannon. He was always more curious than I thought he had any right to be about what was going on with Suzanne and her associates from minute to minute. The Commission’s Report was getting put together, it was going to clear Trotsky and indict the Stalinists, that was all Cannon had any call to be concerned about, but his questions didn’t end there. I sensed he was irked that a group of brainy people working on matters vital to him were beyond his control.

At one point he cornered me to insist that a certain formulation in the Report be worded in a certain way. There was no world-shaking principle involved, it really didn’t matter one way or the other, but I saw he was dead serious about this, meant it as a test of strength. When I next saw Suzanne LaFollette I passed on Cannon’s views without comment. Suzanne was smart enough to see that the issue was trivial in itself and that Cannon was simply trying to flex his bureaucratic muscles a bit with the heavy heads. She gave me a message for Cannon which I took some pleasure in delivering: under no circumstances would the passage in the Report be worded his way, further, he was to lay off, the Commission was in no sense an arm of the Trotsky party and did not intend to let itself be so used.

Cannon’s craggy face clouded over when I repeated Suzanne’s words. His cheeks got very red. His tight lips moved just enough to say, “Those pigfuckers.”

I thought of a man capable of calling literary people pigfuckers because they didn’t accept total dictation from him, of such a man rising to the top position in a new workers’ state. I thought of how intellectuals might fare under his short-tempered regime. (Workers too.) I was very sure I’d be in bad trouble if I were among those intellectuals. This was not speculation. We’d had 10 years of Stalinism in Russia. We’d seen a lot of valuable writers disappear into Siberia, from Victor Serge to Isaac Babel. (Serge was to appear again but not Babel.) And many others of no proven value, many not even visible, like me.

So—I was ashamed of the incipient writer in me on several interlocking grounds. On the one hand, because he wasn’t getting anything done, he was being carefully sat on. On the other, because such an inner man, if he could get out, would not be an object of admiration in my circle of activists. I couldn’t get him in the open, I was afraid of the hoots and catcalls he’d be greeted with if I did. Damned if you do and damned if you don’t.

But he wasn’t to be sat on entirely. It was too damned cold in that dining room in Coyoacán. I huddled there in the small hours with my detriggered Luger and began to write a short story. A young fellow is opening his eyes in a bare room. As they focus he begins to study the cracks and flakes on the ceiling. Lying on his cot, he traces all sorts of significant items on that dingy, crumbing rectangle.

As I remember I did a stunning job of bringing that decaying ceiling all the way to life. Cosmic overtones were discovered in the expanse of sooty plaster, proliferating symbols in each irregularity, each flyspeck. I wrote the opening pages of this story, then wrote them over, then recast them a third time, and that was just warm-up. The trouble was I couldn’t get past that ceiling.

I know exactly why I lingered so. Once I’d exhausted the potential of that ceiling, milked it of all its meaning, I would have to go on to other matters, look into my main people, get a situation set up and some sort of story going, initiate some action—and I didn’t have the least idea where to go once I left the ceiling and came down to earth.

The writing was more or less matchless. I think I’m safe in saying that the literature of the Western world contains few passages about ceilings so impactful. Writers know that some of their best writing gets done in this static mood, this kind of endless lingering over a trifle, inspired by a dread, really, of moving along, of plunging in. Far easier to stay put, meander, blow trivia up into larger—and more inert—than life elements.

This sort of writing is the literary equivalent of jogging in one place. Its source, I will insist, is a serious blockage, an inability to carry a project through to the end, see the people, grasp their situations, develop an interactive dynamic between them, get them into motion toward some culminative finale or at least some turning-point. The incapacity to move forward can generate a lot of sideways crawling.

I’m saying, in short, that a great deal of eloquent prose, at times extremely effective, is triggered by a massive writing block. So much for the simple souls who are undialectical enough to think that the writer who’s dammed up doesn’t produce words. Look at Hemingway. He made a whole new kind of literature, think of it what you will, out of the minimality that comes from chronic clogging. He made stoppage into a style. That’s not to say that Thomas Wolfe was not a torrential bore.

So there were my endlessly rewritten pages about the forever disintegrating ceiling as observed inch by inch by the permanently immovable young man, all of them buried under piles of newspaper clippings and press releases about the Moscow Dials. And Eleanor Clark came visiting.

Eleanor (now, and for many years past, Robert Penn Warren’s wife) was very young but already beginning to be known as a writer of talent. She was aside from that an editor at Macmillan’s—all in all a figure from the literary world. She and the Czech were rummaging in the papers on the work table one afternoon when I was off in town trying to find out how many limonadas con tequila I could wash down with limonada con tequila. They found those pages about the ceiling and were struck by their lack of connection with the Moscow Trials or anything else this household was concerned with.

Thinking it over today, I suspect they liked the writing, though it gave no indication of going anywhere. Chiefly what impressed them was the painstaking evocation of a moribund ceiling. It was a whole new note in literature. Recent fiction had tended to slight ceilings, being fixated on sidewalks and gutters. When I met them later for a drink they asked a natural question—had I written those pages?

With the rapidity of a tic, a reflex, hand flying from hot stove, I said—no, what pages were they talking about? They described the pages. I said I’d never heard of them and had no idea where they might have come from.

When a grown man is accused of unzipping his fly in a kindergarten playground, if even the thought of so doing has crossed his mind once or twice, he will loudly and hastily deny it. It was in similar spirit that I washed my hands of any responsibility for those pages. The thing about furtive writers is that it is hard for them to make a clean breast of it in public, they being addicts of the dirty breast.

It was slashingly clear from the circumstances in our household that nobody else with access to our premises could have written those pages and deposited them on the dining-room table. A fair number of people in our circles, no doubt, had spent time in close proximity to ceilings of this order of decrepitude, but I was the only one who might be trying to recapture them on paper.

Eleanor was a sensitive and sensible girl. She understood without more being said that it was of burning importance to me to disown my words, though she couldn’t have guessed at all the complicated emotions that led me to it. She changed the subject.

The minute I got back to the house that night I burned the pages. It’s really too bad. That was a most superior rendition of a decomposing ceiling; I’ve never seen it equaled. I’m sure I could make good use of it in this or that book, now that I’m putting my name on my words. No matter what kind of story you’re writing there’s bound to be a ceiling in it somewhere, or room to work one in.

You’re probably confused about the time element here. That would be because I am. This has been coming out in a jumble for the simple reason that that’s how it came in, that’s how the years happened and looked. I’m trying to give the facts as they showed up, in all their sprawl, not a writer’s tidy-up, which always calls attention to the tidier and slights or distorts the facts.

There was no continuity in our lives in those days, just a stewing around with now this bobbing to the surface, now that—that’s my point. If you want the truth I don’t remember the porno months in the context of the calendar at all. They don’t fit into the slot after Munich and Maginot, no, they stick in my head as the time I wasn’t rolling my own. In those years we used to come together in somebody’s room with several of those devices for rolling cigarettes out of cheap bulk tobacco, and play poker and roll, talk politics and roll, drink and roll, sometimes just smoke and roll. When I got into porno I gave up these homemades because I had enough money for store-boughts. During my porno months I was nice to myself, I treated myself to Murads and Melachrinos, so to me porno will always have the faintly musky odor of exotic Turkish tobaccos, will, as a matter of fact, suggest shapes oval rather than round.

Art makes order out of chaos, do they still teach that hogwash in the schools? It’s liars who give order to chaos, then go around calling themselves artists and in this way give art a bad name. Here high up on their cerebral peaks are all the artists sifting and sorting out the facts and pasting them together any old way to show how neat it all is and how they’re at the controls of the whole works, and there under their feet the facts go on tumulting and pitching them on their asses over and over, and what’s the whole demonstration worth? Don’t tell me the real artists are tidiers. Céline is in the grand spatter business. Henry Miller spatters too, though a good part of the time by plan, by program, and that’s his tension. Hemingway held it all in his tight hand and pretended it was one packed ball of wax till the end, then his true spewing self came out and he spattered all right, spattered all his order-making brains over the living room, and the lie of having it all together was done for he arrived at the moment of going at his authenticity, his one moment of truth. When do you see Dostoevsky laying out his reality with a T-square?

No, the ones who want to make a big display of how they master facts through words, all they master most of the time is words. The words tend to get in the way of the facts. The words get to be lies because they don’t reflect and illuminate the runaway facts, they conceal them. The worst thing about an art that’s forever making packaged sense out of the world is that it leaves no room for the randomizing senselessness that pervades most of the daily scene. In Hemingway’s neat print world held together and presided over by the code of grace under pressure there’s just no room for graceless berserkers who with enough pressure blow their heads off—such unstyled people are even made fun of, and often are Jews.

What a new and exhilarating art we’d come to, finally, if artists set out to feature the amuckness of the world instead of their own imposed and irrelevant designs—an art that faced the simple roughhouse facts and told the plain ramble-scramble truth—revolutionary! This is by way of saying that I mean to tell this story, no world-shaker, I admit, I insist, in the hit or miss way it happened. If at times I seem to go every-whichway, well, that’s pretty much how things were going back there at the tail-end of the rampageous Thirties, without let-up, around the clock, and it seems to me all that needs recounting, not rendering.

I hope I’ve shown you in these introductory words where I was before porno—nowhere. On the outer limits of all matters. Limbo. Beyond any pale you care to name. You will appreciate that porno came into my life not as a pardon or commutation of sentence, nothing that histrionic, but at least as an opportunity to discharge some words from that mass of language pent up and squirming in me, a needed bleeding in the last skinny nick of time.

It had to appear to me as a bountiful gift from the gods I did not believe in. I clutched at it as the drowning man at a cabin cruiser, one well stocked with supplies and, more important still, equipped with a powerful shortwave radio.

Somebody out there in the wide, wide world actually wanted me to write something. They wanted my words. They were more than ready to pay me for them.

I’d be eating, the precondition for writing. I would write, the only way I knew to eat. Words and money had finally been introduced to each other in my life and made partners in my head.

I suddenly felt wanted. Not, for once, by the authorities; they assuredly were much too busy looking for my employers.

I’m going to stop calling it porno. The vowel ending makes the stuff sound Italian or Spanish, something foreign and a little greasy, an importation, which is far from the facts. Without question this country has had its own homegrown or homespun pornography as long as it’s had a Constitution, very likely as long as it’s had printing presses.

I suspect that the Puritan fathers, by emphasizing how many things in this world were pornographic either in quality or potential, succeeded in calling the public’s attention to this whole area of life. There’s nothing like a negative endorsement from the clergy to get the public interested, stir up a good word of mouth, as they say in PR, when you’re introducing a new product a bumrapping from a churchman is worth more than any special introductory offer, 30-day trial with no obligation to buy, money-back guarantee, 5,000 Blue Chip stamps for bonus, entry in the milliondollar sweepstakes with each box top—look how a Boston banning used to make any sappy book into a bestseller.

From here on in I’ll call it porn. Porn has a very American ring to it. It sounds a little like corn and a little like pone, and cornpone’s about as American as mom’s apple pie, a product, by the way, which by a sort of backlash effect has made a lot of Americans run toward pornography pretty much for the same reason that the diabetic runs from sugar.

You see, then, what I’ve been trying to do in these opening pages, give you some picture of me preporn, preborn.

The setting: I was dividing my time between New York and New Haven (my home town, if I haven’t made that clear). I’d be unemployed in New York for a while. I’d get out on the Boston Post Road and hitch a ride east. I’d be unemployed in New Haven for a time. I’d get out on the Boston Post Road and hitch a ride going west. I rolled a lot of homemades in both towns, maybe a few more in New Haven because I had my family there, and there were trees to walk under, and snow wasn’t processed into a slushy gray muck 10 minutes after it fell. Then through some fluke I got a job in a factory up in Bridgeport. Then this girl Bettina wrote me from the Village. She’d run into this woman named something like Zoma or Zo-Zo. Zoma or Zo-Zo knew this fellow named Barneybill who had some things going. If I wanted to come down and meet Zo-Zo in order to get to meet Barneybill I might, it was just possible—read on, you’ll find out how it all happened, how from the very pyorrheic jaws of crisis I snatched the loose tooth of identity. . . .

This is going to be hard, I feel myself tensing up, I’m not used to writing about myself. Not that I’m coy, I just get restless looking at the same thing day in, day out. I’ve got a short attention span, which discourages autobiography.

Some writers write nothing but successive editions of their autobiographies in various fake guises, telling even more lies than straight autobiographers do. I can’t put myself in that self-circling frame of mind and don’t warm up to people who do. (Céline excepted. Céline looks so hard and deep into his insides, he sees the whole damn world deposited there.) A page sprinkled with first-person pronouns puts me off. People whose subject is forever themselves seem to me to be operating under two handicaps, one, that they suffer from tunnel vision, two, that they don’t have much to say, a characteristic of tunnel workers. On their horizons their own persons bulk so large as to blot out the world about, and without a not-me surround to point up where they end and the impersonal materials begin they can’t even see themselves, their one subject. Writers who are eternally running round and round inside their own heads and recording each lap for posterity will eventually tamp down and deaden major portions of their brains, that delicate stuff isn’t built to take a heavy foot traffic, it’s there to be used, not trampled on.

Paradox: the more you comb through your insides the less you come up with to write about. Besides, there’s more to look at out there than in here, and it’s less fogged over. You’ve got to learn more from three billion people than from one, it’s a matter of arithmetic. Again, it’s the writers who keep their eyes on the world about who tell us the most about themselves. What’s a man after all but his vision? Blinders and all? What’s he going to convey to us about his vision if he keeps it trained on his own insides, which he’ll never see? But I suppose every writer has to do this me-myself-and-I softshoe one time out, to show how versatile he is and that he hasn’t got two left feet.

Stay with me, I’ll get the hang of it. I think we can begin. . . .