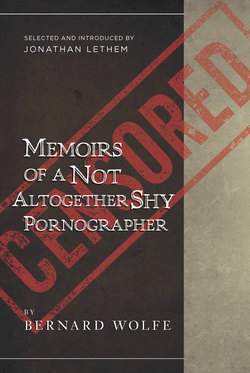

Читать книгу Memoirs of a Not Altogether Shy Pornographer - Bernard Wolfe - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION BY

JONATHAN LETHEM

Bernard Wolfe’s Memoirs of a Not Altogether Shy Pornographer comes into your hands as a book-out-of-time. Such republication efforts as these always collapse the shallow literary present into a more complicated shape, making a portal through history—who is this lost writer, we ask ourselves, and what is this lost book? But also: what views of a lost cultural landscape might be available through the portal this particular lost writer and lost book represents?

Make no mistake, the case of Bernard Wolfe is an especially interesting one, not least because, even in 1972, in the pages of his memoir when it rolled fresh off the presses into the hands of god-knows-how-few readers, Wolfe already presents himself as a man-out-of-time, in ways both helpless and defiant. Wolfe’s career was bizarrely rich: from time as Leon Trotsky’s personal secretary to stints in the Merchant Marine, as ghostwriter for Broadway columnist Billy Rose and author of early-TV-era teleplays, as editor of Mechanix Illustrated, and as exponent of the theories of dissident psychoanalytic guru Edmund Bergler (whose homophobia was obnoxious, but whose discarded theories strongly anticipate later thinking, and who could be seen as a kind of “lost American Lacan,” if anyone was digging for one), to his glancing participation in the realm of American science fiction, and his role as amanuensis, to jazzman Mezz Mezzrow, in writing a memoir depicting a prescient version of “hipsterdom” and which became a kind of bible of inner-urban American slang—Wolfe was practically everywhere in twentieth-century culture.

Yet Wolfe was also nowhere, in the sense that the present interest attaching to him doesn’t stem from the notion of “reviving” a writer with an earlier purchase on either popularity or the embrace of literary critics of his time. Wolfe had neither. A few of his books sold a bit; Limbo has kept an obscure reputation within science fiction and bobbed back into print a few times. Yet for his hyperactivity, Wolfe had little traction, and in 1972 was hardly a writer whose memoirs any publishers were likely to be clamoring for. Wolfe, restless, fast-producing, and seemingly impervious to indifference, wrote one anyway. When he did it was surely the “pornographer” of the title that drew Doubleday’s interest in publishing the result.

What the reader meets here is both fascinating and truly eccentric. The book is a writer’s-coming-of-age narrative, but a highly unsentimental one, describing Wolfe’s location of a habit and a craft and a discipline and a capacity, much more than it details his discovery of any definite sense of purpose as a writer. Wolfe’s vibrant intelligence, which picks up and turns over any number of vital subjects as if they were rocks concealing scuttling insect life, rarely settles on introspection, let alone seeks a tone of confession or remorse or self-doubt, such as we’d expect from nearly any memoir lately. Despite this, there’s a terrible poignancy to the material concerning his father’s spiraling mental illness, and the bizarre ironies attaching to Wolfe’s own role as a New Haven-townie-gone-to-Yale who gets a psychiatric fellowship at the same institution in nearby Middletown where his father is a semi-comatose inmate. Of course, a commissioning editor, nowadays, would have insisted that Wolfe punch this material up, goose it emotionally, and put it in the foreground (a contemporary point of comparison might be Nick Flynn’s fine Another Bullshit Night in Suck City). The same imaginary editor would surely, I think, have asked Wolfe to excise so much of the fading political context from the book, but for various reasons one can guess this book wasn’t so much edited as it was simply written and published. It’s in the politics that one can feel how deeply, and restlessly, Wolfe was, by 1972, testifying from an already-lost world. His passionate and still unresolved commitment to Marxism, a commitment betrayed (of course, and in so many different ways) by twentieth-century historical reality, remains the lens through which he views the “labor” of writing, and the social relations into which he projected himself as a hungry young writer in the wartime years.

Despite his engagement with history, there’s no attempt to make a wide-screen historical panorama of his book—what enters of political and cultural context does so through individual experience. Wolfe also doesn’t trouble much over the question of censorship, despite the great battles over Ulysses, Lolita, “Howl”, and others that he’d certainly be capable of drawing into the mix. Apart from Henry Miller, and one other generationally important writer who comes in as a bizarre punch line, late in the book, Wolfe doesn’t drop names. He doesn’t situate his writer’s life in terms of movements or generations, apart from dividing his future efforts from the drab proletarianism he sees as the Marxist writer’s obligated legacy.

That the “labor” young Wolfe found for himself was to create exotic, gussied-up porn novels for the private delectation of gentlemen-collectors, or maybe just one gentleman-collector—talk about your lost worlds!—is a perverse irony of which the book makes its primary meat. Not that the memoir is salacious in any way (in fact, Wolfe can seem prim), but the situation forms a puzzle for the young writer, one the older Wolfe’s still captivated by: how did I get here and what could it possibly mean? The book is a portrait too, a poison-pen portrait, of the disappointed, pretentious, and disingenuous publisher/go-between for the porn novels, who Wolfe calls “Barneybill Roster.” In his luxuriant and fascinated distaste for this man, Wolfe himself resembles Henry Miller in the grip of one of his long denunciatory ranting episodes, like his great novella A Devil In Paradise. This brings us to the matter of the book’s style—the weird, cavorting, punning, ruminative, aggrieved and deeply humane style that was Wolfe’s own. Like many things in the book, Wolfe’s astonishing and peculiar voice is deeply individual, but also historically characteristic. It shows, to me, the way Joyce’s influence, but also Henry Miller’s, was essential in the development of so much colorful “voice” in mid-century writers as seemingly otherwise unallied, or even divergent, as Mailer, Kerouac, Brautigan, Pynchon, Philip Roth, and so forth. Wolfe, in his novels, never quite rose into that company—his restless and motley enthusiasms may have catapulted him in too many directions, and he may simply not have had the luck or even the desire to apply such fixity to the novelist’s art—he’s almost a monologuist, a stand-up man, like Lenny Bruce or Lord Buckley. But the fellow who writes, here, “Words are problem-prongs” was a great man of language, and it’s a gift to be able to read him again. Wolfe lives.

— JONATHAN LETHEM