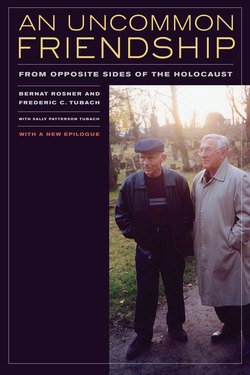

Читать книгу An Uncommon Friendship - Bernat Rosner - Страница 9

ОглавлениеONE

The Return of the Past

We humanize what is going on in the world and in ourselves only by speaking of it, and in the course of speaking of it we learn to be human.

HANNAH ARENDT

The end of the journey came five days after the train left Kaposvar. People spilled out of crammed cattle cars onto the platform of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp on a foggy morning in July 1944. The bodies of those who had died were left behind in cars whose heavy sliding doors had been barred shut the entire trip with iron and barbed wire. The only light had filtered through narrow ventilation slats, and the terrified victims now blinked in the daylight, looking for friends and family members on the platform. They shouted out names in Hungarian —Pista, Jozsi, Sanyi, Kato. But SS guards ordered silence, striking with rifle butts anyone who was too slow to stop searching for a familiar face or calling out names.

Twelve-year-old Bernat Rosner was unloaded from a cattle car together with his father, mother, and younger brother. Bernat tried to hold onto the family's small pile of possessions and to keep it separate from the others. He caught a brief glimpse of his Uncle Willy and of Jenö, one of his older cousins and playmates back home. But then he lost sight of them in the crowd.

All of those who had been designated car “leaders” before their departure by the SS crew in charge of the deportation were ordered to report to the camp authorities. As the leader of their freight car, Bernat's father did so, and disappeared—forever. Bernat and his ten-year-old brother, Alexander, soon joined the men and boys, but not before their mother admonished them to stick together. Then she too vanished forever, like their father had just a short while earlier. Now the two brothers stood in a group of males on the platform in the camp —a desolate, flat place surrounded by a heavy chain-link fence, topped with coils of barbed wire.

In summer 1983 I was invited to dinner at the home of Bernat Rosner, Auschwitz survivor and husband of my wife's high school friend. Sally had run into her friend again by chance after twenty years. When Susan Rosner asked us for dinner at their house, I reflected on the fact that most Germans of my generation and younger had not known any Jews personally— or, if so, only fleetingly—because when we were young in Germany, the Jews among us were removed from our midst and exterminated. As a German American, I returned to the United States, studied and worked at the University of California, and lived among Americans, some of whom were Jewish.

During my years in Berkeley, I met only a few concentration camp survivors. One such encounter took place in the staging area of an academic procession near the campanile on campus. I paired up with a Czech lecturer waiting in a crowd of professors for a march to the Greek Theater, where a graduation or a visiting dignitary was to be celebrated. The woman, in her late thirties and with chestnut hair, was a friendly colleague on the fifth floor of Dwinelle Hall. My office was in the German Department, and hers was around the corner in the Slavic Department, which we both referred to jokingly as “the Polish corridor.” There, at the base of the campanile, we were all wearing our academic robes and mortarboards, and the atmosphere was festive. I was shocked when the San Francisco Bay breeze suddenly raised the sleeve of her gown to reveal a concentration camp number on her arm. It contained, among other digits, a seven, with the characteristic German side cross over the down stroke. Looking back, I have sometimes wondered whether I offended her by asking where and when she was so marked. Her answer was simple: “Auschwitz.” Then she continued to talk about other things in a casual manner. She also bore a deep half-moon scar on her chin that might well have been inflicted on her by a jackbooted guard; but at the time I couldn't bear to put the two things together in my mind.

I felt apprehensive about the upcoming evening with my wife's old schoolmate and her husband. It would have been easier to watch a documentary film or to participate in an academic discussion on the rise of Nazism and the Holocaust. This dinner for four could be attended by uninvited guests —any of the dead members of his family or of mine. Perhaps my distant uncle, who had been an SS officer in charge of a refugee camp near Würzburg and hanged by the surviving inmates at the end of the war, might appear. Or perhaps my own father in his Nazi Party uniform would join us for dinner, or my host's father and mother as they emerged from the ashes of the crematorium.

When I was introduced to Bernie, as he now called himself, I was convinced that he was older than I. He looked worn out from his job as general counsel of the Safeway grocery chain headquartered in Oakland. His days at the corporate head offices were obviously more hectic than mine as a professor at the university in nearby Berkeley. No wonder. The revolutionary days of the 1960s and 1970s had passed. The campus atmosphere was more “academic,” though Berkeley never became a tranquil place for quiet contemplation. But Bernie was the lead attorney in a field where the financial stakes were high. We had our battles at the university, too, but as Henry Kissinger once described the paradox at Harvard, university turf wars were fierce because the stakes were low.

Although the subject of concentration camps didn't come up over dinner, I couldn't help thinking about it. I noticed that Bernie had light blue eyes. Words from the “Todesfuge” (Death Fugue) of the Jewish poet Paul Celan, a camp survivor who later committed suicide in Paris, crowded in on me: “Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland sein Auge ist blau” (Death is a master from Germany his eye is blue). I repeated them several times to myself, re-creating in my mind the ritual intensity with which they are repeated in the poem. As a child I was told that I had inherited the blue eyes of my mother, who died before the war, when I was three years old.

From these self-absorbed reveries, I looked again at our dinner host and decided that perceptions were a result of the moment. Now it seemed to me that he had the upturned mouth of Frank Sinatra and could easily pass for his first cousin, if not his brother. No hint of Auschwitz there. I noted that he and I, both on the short side, were just about the same height. He was slight and wiry, while I had to watch my weight. What little hair he had left was sandy brown, while I had all my dark but graying hair. I probably looked more “Jewish” than he did to those who saw people as stereotypes. My mind drifted to my father, who told me once of being terribly afraid of a barber in Germany who had asked if he was Jewish. My father denied it, insisting that appearances can be deceptive, but he had the feeling the barber didn't believe him and would have liked to have cut his throat with the straight-edged razor he used to shave him. The dinner conversation with the Rosners escaped me for a short time, but no one seemed to notice my silence. And my free associations about blue eyes, appearances, and barbers faded away. In reality, Bernie is a year younger than I am.

As it turned out, the hours passed quickly during that mild summer evening in northern California, when the setting sun suffuses the air with a pale yellow tinge. World War II was two generations behind us. The past seemed far away. We stayed late to sip cognac and watch a sampling of Bernie's video collection of grand opera. The Rosners had a large-screen television, and with several remote controls Bernie could tune in the finest arias of Mozart or Verdi. Classical music enveloped the living room as we listened to excerpts from Strauss's Der Rosenkavalier. Who, at our age, would not be touched by the Marschallin's musings on time as a wondrous thing—“Die Zeit ist ein sonderbar' Ding.” Wouldn't it be best for both of us to just surround our pasts with the detached glow of great music?

After this first dinner, I didn't know whether we would see the Rosners again. But when we reciprocated the invitation and they accepted, we began to develop a pleasant, if superficial, suburban friendship. At first our wives encouraged and held it together. They had shared an upper-middle-class background in southern California and had some common friends from the high school they attended in Pacific Palisades in the early 1960s. As couples we had similar interests —in good food and wine, tennis, travel, culture, and contemporary affairs. When it came to our pasts, Bernie and I could easily talk about our early childhoods. It turned out that we both grew up in European villages. Bernie was born and raised in the Hungarian village of Tab, located southwest of Budapest, where his parents cultivated and sold fruit and walnuts. And although I had been born in San Francisco, I also grew up from the age of three in a village — Kleinheubach, on the Main River, about 75 kilometers southeast of Frankfurt. We both knew the lazy days of summer when nothing moved during the midday heat aside from the swallows that swarmed with high-pitched screeches over red-tiled roofs or flew low over the cobblestones to signal the arrival of a late afternoon thunderstorm. Growing up in a village gives you a special sense of place and the physical appearance of things: the polish of smooth-worn stone steps; the penetrating smell of wax and Lysol in the school buildings; the fierce look of the scarecrows that were supposed to protect the cherries on the neighbors trees but instead frightened small children far more than the pesky, ever-present sparrows.

Though small, the villages of our youth were connected to the outside world by trains that stopped several times a day. This limited traffic didn't prevent weeds from growing up between some of the tracks. Because we knew the train schedule, we could use the tracks as a shortcut to the nearest fishing pond, thereby avoiding the dusty roads. Our villages had few lights, so that day and night were sharply demarcated, as were the seasons. A quiet life characterized our early childhoods.

But the parallels in our lives ended abruptly one day in spring 1944 when the SS and their Hungarian Nazi henchmen arrived in Tab and deported the twelve-year-old Bernie, his family, and the other Jewish inhabitants to Auschwitz. In the summer of that same year in Kleinheubach, when I was thirteen, I was a member of the Jungvolk and slated to become a Hitler Youth. My father, a full-time employee of the Nazi Party, became a lieutenant in the German army. Most of my family, including my father, survived the war. Bernie's family perished. He is its only survivor.

When you emigrate to America, you turn the pages of your life quickly. If you don't do it yourself, the country will do it for you, or you'll be “history,” as they say. This is America. In contrast, a contemporary German writer recently stated that not a day had passed since Auschwitz. That is Germany. As our acquaintance deepened into a friendship, Bernie and I were caught for more than a decade between our European pasts and our American present, and neither early childhood memories nor the many things we now had in common were enough to bridge the divide that had existed between us during the years when Hitler was in power.

Bernie's experience of Auschwitz and the disappearance of his family and my German upbringing and Nazi father couldn't be discussed over dinner. I couldn't just say, “How was it?” or “Tell me about it, Bernie.” There was no adequate way to broach the subject. But neither could we ignore these facts; they were close by, somehow, whenever we met. The Holocaust had become an important topic of academic research, but in spite of all the insights that have been gained, the distance between the trauma itself and present reflections on it has inevitably become greater. Once, during a cocktail party at our home, I happened to hear a well-known Berkeley professor mention to Bernie that he had just returned from a conference on Auschwitz in Hamburg. Bernie replied, “I was there—at Auschwitz, I mean.” For a moment silence ensued, and then my learned colleague changed the subject. The gulf between the Auschwitz victim—an uncommonly articulate man—and the normally communicative scholar, well versed in the current academic discourses about the Holocaust, was striking. These two party guests had little to say to each other.

After I had known Bernie for a year or so, Auschwitz drifted into our conversation inadvertently. But Bernie was reluctant to dwell on it. He told us, as he has told many people in America over the years, that he had lived two different lives —a childhood in Europe and an adulthood in America —and that the first life had nothing to do with the second. He obviously wanted to leave it at that.

At the end of one of our dinners—in fall 1989—the Rosners mentioned that they were planning to visit Hungary and Bernie's village, Tab, the following summer. They suggested that we join them, and we agreed. I was going to be on sabbatical in Europe, and we already had plans to see Hungarian friends in Budapest, so the timing was right. We decided to meet in Budapest and drive to Tab.

When Sally and I reached Budapest in the late afternoon on the appointed day, we were delighted to find that our friends had arrived safely and were already in their room at the Hotel Buda. The next morning we spread a road map on the hood of our rented car and plotted the route from Budapest southwest to Tab. Sally, our designated driver, negotiated the Hungarian traffic while Bernie navigated us toward his native countryside. On the way we caught up on each other's lives. Bernie must have thought about it, but until we arrived at Tab, it seemed as if the rest of us had given little thought to the fact that we would be visiting not just the village of his childhood but also the village from which he and his family had been forcibly torn by Nazis. Much later I realized that in proposing this trip, Bernie had emphasized the tourist aspects, since at that time he kept his life as Nazi victim far away, if not entirely from himself, certainly from the persona he presented to the outside world, including his friends and family. For Bernie and me, however, it turned out to be the beginning of a journey that took us far beyond the one-day trip to his native village.

About an hour and a half out of Budapest, we approached Tab. Small side roads to orchards, plowed fields, and groves of trees, marked the rolling landscape. Once in Tab, we parked the car near the railroad station, and Bernie became our guide. Our vacation mood changed, and our animated conversation faded as the reality of Bernie's past came into focus. We walked slowly down the main street as if picking our way through a minefield laid down by history. Bernie oriented himself by identifying places where particular houses had stood many years ago. At the end of the street was a tavern of the type one finds all over Europe, filled with men who, over a late morning snort, tell each other how things are with the world. They hardly took notice of us as we entered to use the rest room, except to tell Bernie the way to the Jewish cemetery when he asked in his halting Hungarian.

We walked up the dirt road that led past a row of modest houses. Between two of these houses, Bernie pointed to a broad flight of stone steps that stopped abruptly at the top of a slope where the synagogue had once stood. Now there was nothing—no memorial, no sign—just these steps, crumbling, deformed, and partially covered by clumps of grass. We made no effort to climb them. As a boy, Bernie must have trod them many times on his way to and from the building that had once stood there. I thought of the railroad tracks in Shoah that stopped at the entrance to the Treblinka extermination camp, tracks leading to a dead end, like these steps that now led only to an empty plot of earth and grass.

We walked on, saying little. Gray clouds shifted over the distant fields. At the edge of the village we continued beyond the last houses on a dirt path that led to the Jewish cemetery. Enclosed within a rickety fence and partially bordered by trees, it was abandoned and overgrown with weeds. We forged our way through the surrounding hedges and a hole in the fence. Tall grass, still damp with morning dew, hid many of the grave sites. Bernie looked for names he might remember, names of family and friends, and found a few. Reading the stone slabs, he told us the profession of this or that person and related a few anecdotes in a matter-of-fact way—fragments of life from his normal childhood, before things changed. At one edge of the cemetery, almost hidden beneath the trees, we came across an abandoned coffin and cart that had been used to transport the deceased from the village to their burial place. The cart had been sturdily built, so that even with the passage of more than forty-five years the wooden planks were only partially rotted. Bernie became animated, as if he had made an archaeological discovery. He knew people who had been taken on this cart to their resting places. I felt an aversion to this smug Hungarian village for neglecting the cemetery, for allowing the coffin and cart to lie abandoned and exposed to the elements, for forgetting its former citizens and letting the weeds grow over their graves.

Bernie asked us to leave him alone for a while in the cemetery. So Susan, Sally, and I made our way out through the broken fence, down to the main road, and headed back in the direction of the village below the constantly shifting clouds in a sky that was beginning to clear. We walked slowly so that Bernie could catch up with us. He seemed small and alone as he approached us from a distance. I realized that he may have been the only one of his people to have survived and to have revisited this village. To my amazement, he was striding lightly when he rejoined us. His step had an unexpected buoyancy. We talked about wholly different things, and I suddenly had the feeling that four American friends, whose present lives had hardly anything to do with this place, walked like tourists back toward the main street of Tab. I now know that Bernie wanted it that way.

We made another stop at the tavern. The same men were still talking and drinking. Again, they seemed to take little notice of us. Would they have cared had they known why we had come to Tab? A couple of them might have been old enough to have known the twelve-year-old Bernat or his ten-year-old brother or his mother or father before they were taken away. Why weren't they more curious when they heard this foreign tourist speaking in broken Hungarian?

The walk back down the main street seemed long. I thought of the three burial grounds in my childhood village of Kleinheubach—the Protestant cemetery, the most prominent and the one closest to the village center, the Catholic graveyard, next to a main road that used to be about a ten-minute walk beyond the last houses, and, finally, up on the east slope of the Odenwald, the Jewish cemetery, located in a forest, not unlike the graveyard in Tab. On my last visit to my village, I had taken a walk past the Jewish cemetery. Partially hidden behind high walls, it was locked up tightly. A German sign posted on the gate read, “Anyone defacing this cemetery will be punished by law.” This warning was signed by a former mayor of Kleinheubach, Herr Lippert, who had been a member of the Waffen-SS during World War II.

The main street of Tab brought us back to the railroad station. A semideserted, two-story building, its paint was peeling. Cobwebs hung across some of the doors. Printed signs were yellowed with age. This country station, which looked abandoned like so many train stops all over rural Europe, came to life even in 1990 only twice a day. As we approached, the station appeared quiet and forlorn. Just as in Bernie's youth, the building was inscribed with the word “TAB” in capital letters. Our car stood where we left it. The only sounds were the electric humming of summer crickets and the buzz of low-hanging telephone wires. The clouds were gone, and the sun beat down. Nothing moved. Silence enveloped us for a long moment. Cameras ready, the four of us stood there wondering what pictures to take before our departure. We decided to photograph ourselves, in front of the station and next to the partially overgrown railroad tracks.

After the picture taking, I noticed that Bernie's eyes were fixed on a couple of run-down brick buildings dominated by a tall chimney near a stand of trees to the west. He didn't move except to raise his hands to shade his eyes from the glaring sunlight. Suddenly he said, “That's the brickyard. That's where the horrors began.” No one spoke. As we climbed back into the car and drove away from the village, the fleeting remark hung there in the summer heat.

After our visit to Tab, various bits of conversations I had with Bernie about his past would run through my mind over the next few years. Despite this visit, I still had only fragmentary knowledge of his early life. He had never told his entire story to anyone, preferring to think that the Nazi terror had happened to a “Bernie” in quotation marks, a different Bernie. Would he someday trust me enough to tell me more? Perhaps our suburban California lifestyle was not conducive to such communication. Or was my German background an unspoken barrier? Yet his untold story, the “other side” of him that was closed to me, did not let go. He wanted it that way at first, because it helped him support the division he had made between his present and past lives. I, however, was left with a desire to build a bridge but few means to do so.

When you are twelve years old you feel immortal. Bernie and I both felt that way then. He had told me that much. I remember looking through an open air vent on the tiled roof of my grandparents' house, feeling invulnerable as I watched low-flying American Mustangs strafing the countryside. I asked myself whether Bernie felt fearless, even invulnerable, while he was being transported to Auschwitz—at least before he came in close contact with the death machine. Is that sense of immortality a privilege of youth, no matter how great the dangers? The danger to his life was incomparably greater than the danger I faced. After all, no one was out to get me, personally. No one forced me to go up to the attic to watch American planes during air raids. And air raids didn't continue indefinitely. But the threat to Bernie's life was ever present. A chance decision by a guard or a general order involving the group of inmates to which he happened to belong could have meant his death at any moment. Or he could have been chosen to become a human guinea pig in the bestial experiments of the camp doctor, the infamous Josef Mengele.

How did this twelve-year-old live his daily life in an extermination camp? In another brief allusion to his past, Bernie had compared his experience as a camp survivor to that of a barnacle attached to an underwater rock. I was struck by this metaphor, the hard jagged shell that protects the animal inside. Do analogies help one to understand the life of another person, in particular a life lived inside a factory of death? His analogy was distilled out of his experiences. I drew inferences from what he said, but they were not enough for me to understand the catastrophe that befell him and his family, notwithstanding my years of training as a professor of German and the textbook I had written on the Nazi period.

It wasn't until the 1990s that I became aware that Bernie had searched for links to his past, to that other life to which he claimed to have cut his ties. In the course of putting down our stories, he told me that before his first trip to Israel in 1995 he had thought long and hard about contacting Simcha Katz, his concentration camp buddy of fifty years before. “Without a buddy you couldn't survive/' Bernie told me after this trip. “With a buddy your chances for survival were a little better, because you could help each other.” But instead of elaborating on their friendship and dependence on each other in the concentration camps, Bernie stressed how the intervening years had distanced him from his former partner. They had corresponded for only six months after Bernie's arrival in America. After much soul searching, Bernie decided to reestablish contact with his old friend as part of his visit to Israel. The result was an emotional reunion at the Jerusalem Hyatt, dampened, however, by trouble communicating. Their native Hungarian had grown rusty, and Simcha spoke no English. Bernie's spoken Hebrew was minimal, and neither of them was fluent in Yiddish anymore. They talked to each other through a Hebrew-English interpreter.

Simcha had immigrated to Israel after the war and raised a family. He made his living as a self-employed paving contractor, and the Rosners had tried to downplay how well off they were in comparison. Although I wanted to hear details about the “buddy system,” Bernie told me more about present matters—Simcha's current life and the Rosners' impressions of contemporary Israel. Simcha did not want Bernie to talk about their experiences in the concentration camp. The pain, as Bernie told me, remained too raw for him, even after so many years. I, for my part, began to ruminate on this glimpse Bernie had allowed into the buddy system and what might have happened to them decades ago behind the watch towers, barbed wire, and electric fences. Too much time had passed, too much had changed for these two concentration camp inmates to find their way back to the days when they both needed each other for their survival.

I thought about my own childhood buddy, Ludwig Bohn, with whom I played chess in summer 1944—at the time that Bernie was deported to Auschwitz. We played our game behind shuttered windows to keep out the heat and humidity. Ludwig and I would take long walks through the countryside, and on several of these forays we searched for a specimen of Goethe's Urpflanze, the ideal prototype of perfection in the plant world. We convinced ourselves that we found the Urpflanze in the form of a particularly tall pine tree in the English gardens of the Prince of Lowenstein's castle at the edge of Kleinheubach. I lost track of Ludwig when I came to the United States. But I found out that he married a woman of German descent in Namibia, a German colony before World War I, and I also heard rumors that he had become an anti-Semite.

Shortly after Bernie told me about Simcha, I dreamed that I telephoned Ludwig in Africa and tried to question him about these rumors. In the dream I reminded Ludwig that we had boycotted some of the meetings of the Jungvolk, the pre-Hitler Youth organization we had to join, preferring to play chess, collect stamps, and look for Goethe's perfect plant. We had considered ourselves better than the clods who ran the Nazi youth meetings. I asked what had happened to him. Why had he changed? But the answer to my repeated questions over the phone was silence. In my dream he did not reply.

I sometimes thought that Bernie and I should just let go of our pasts. I reasoned that if we would simply forget, we wouldn't be suppressing anything. We were the buddies now, but not to survive a death camp or to search for an Urpflanze in a princely park. Why not just have another glass of wine and listen to music, or discuss philosophy or European literature? After all, the 1990s were not 1944. We might just as well take advantage of suburban American life and the easy escape from history it provided.

One day, as we lounged at his pool, I was amused to learn that Bernie could barely swim. He not only admitted it but also thrashed across the shallow width of his pool to demonstrate his uncertainty in the water. I told him about my own water shyness and how as a boy I used to tell my grandmother that I'd been in the Main River all the way up to my neck, when in fact I'd barely gotten my swimming trunks wet. We both had a good laugh. Wasn't communicating such intimate trivia of the past enough? Isn't it exactly the shared bons moments in life that deepen a friendship? Although we enjoyed this pleasant status quo, I wondered whether it could be sustained. Lurking just below the surface of this everyday, after all, were events that remained never more than a nightmare or a phobia away for both of us. Without our being completely aware of it, the walls we had raised around these events had already begun to crumble. As it turned out, something unexpected happened that brought the walls crashing down.

On a business trip to the East Coast not long before his retirement in 1993, Bernie visited the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. The museum was crowded, and when he received a number that would have allowed him to enter too late in the day to make his afternoon flight back to the West Coast, he informed museum personnel of his predicament and of the fact that he was a concentration camp survivor. They immediately allowed him to enter.

In the museum Bernie looked up the Nazis' records of the arrivals at the Mauthausen concentration camp. He had been transferred from Auschwitz to Mauthausen in September 1944. His reaction to these documents took him by surprise. He told me that his heart began to pound as he started to turn the pages on the microfiche machine to the date of his own arrival. When he finally reached the relevant page and ran his finger down the entries, there it was, his name, in an old German typeface: “Rosner Bernat.” Thus he came face-to-face with his experience at Mauthausen. He told me that as he stared at his name, all the steps he had taken in his life seemed to lead nowhere but back to the horrors of that past. He was shaken, and he decided there in the museum that the time had come to confront his concentration camp experiences as directly as possible. These bureaucratic documents that stood for events that he had believed no longer would touch him convinced him to do so. Not only did he want to tell his story now, but he wanted to tell it to me. I felt moved by his decision, yet uncertain about what it would mean.

It became clear that our suburban get-togethers with our wives, our casual poolside or dinner table conversations accompanied by good food and wine, were not the appropriate framework for the telling of his story. So we decided that just the two of us would meet, beginning in fall 1995. By then we were both retired and no longer had to focus our energy on present tasks or on long-term professional objectives. I think that this slight slackening of the will—which Thomas Mann considered crucial for gaining insights into the past—also helped us to bring our histories out of hiding.

Our working method was simple. I took notes of Bernie's oral accounts and rendered them into narrative form. I wrote up my own story in conjunction with his. My wife, Sally, a freelance writer, then worked on organization and English style. After the draft of a section was written, we got together for a reading and discussion, and Bernie made additions and corrections. This matter-of-fact chronicling of how we proceeded, however, conveys little of the difficult path we had chosen to travel together. For one thing, even after Bernie decided to tell me his story, we drifted toward these memoirs, or rather, we backed into them gradually. We had no preconceived notion of a “final product.” That early unselfconscious, naive phase of our joint efforts, when we gathered memory fragments, wrote them down, and discussed them, was crucial for the emergence of the eventual memoirs. And at the outset, we had no idea what obstacles and limits we would encounter on our way—obstacles in Bernie, limits in myself.

The story emerged in twists and turns. At first it seemed

enough to listen to Bernie tell me about his concentration camp experiences in a deliberately detached and factual manner. His initial recollections emerged well thought out and usually presented without hesitation. He was an attorney, after all, accomplished in articulating conflicts and complexities. His verbal facility helped to put me at ease and allowed me to approach a life very different from my own. It helped that we had a silent agreement about the limits regarding what needed to be or should be articulated. But then, sometimes a year or more later, heartrending facts would surface when he made new “stabs into his memory bank,” as he called them. I slowly learned that “sticking to the facts” and recounting them as rationally as possible was also Bernie's way of not seeing that these facts had inflicted wounds. It took him time to admit this.

To maintain the separation between his two lives, during our visit to Tab in 1990 Bernie had downplayed the trauma he had experienced there. And true to his American persona, it was late in our work that he admitted to me his compulsive desire during one period of his adult life to return to Tab, to revisit the places where his parents had lived. During this period, he even purchased a detailed map of the region and memorized all the train stations between Tab and nearby Siofok.

As for me, I narrated my story believing that my good memory and grasp of details in their historical context would be a reliable guide to my own past. I learned, however, that what one puts in and leaves out—what one likes to remember or prefers to forget—also tells a story, one that is difficult and occasionally impossible to narrate. But over time, as I saw Bernie struggle with his own past, it was natural for me to look at myself, at who I am now and what made me this way. Bernie encouraged me to do so.

Someone asked me why I wanted to know Bernie's story at all. For one thing, because the German crime of the Holocaust never lets me go. But wanting to know about Bernie's “first life” was only part of what motivated me. I also wanted to link it to my own story. To do both, to tell his story and mine—the Hungarian Jewish boy and the young German villager trapped on opposite sides of a mortal divide, who come to America where their paths cross and they can work and play together—this new undertaking came to form the crux of what was important to me: bridge building. I simply refused to accept the fact that the deadly barbed wire erected by Adolf Hitler and his henchmen half a century ago would forever mark us off from one another in a fundamental way, that Hitler would have the last word in how we could relate to each other. The murderous events had been too horrendous to ignore in our emerging friendship, but I didn't want to grant the Nazis the power to perpetuate that divide indefinitely into our present lives.

It was Bernie's desire to have his story told in the third person, thus making it accessible to my narrative voice. I approached this role with apprehension. My narrative voice would be that of an outsider to the Holocaust, a German one at that. Would this constitute a sacrilege? Should I have maintained a discrete distance from one who had “returned from a descent into hell”? Should I have urged Bernie to tell his story in his own voice? He did not want it that way. He wanted us to look at our pasts together, because he believes that reverence for the extraordinary trauma he experienced can sometimes have an exclusionary effect; it can bar entry, define outsiders and keep them at a distance. It can create an inner circle of empowered narratives that renders the past less accessible to others. Toward the end of our work, I asked Bernie what had persuaded him to undertake this perilous journey with me. He said it was our common European cultural heritage, with its Utopian longing for a civil society and the shared experiences of great art, and as for the rest, we agreed with Peter Ustinov's dismissal of ethnic and religious identity: one should have one's roots in civilized behavior and leave it at that.