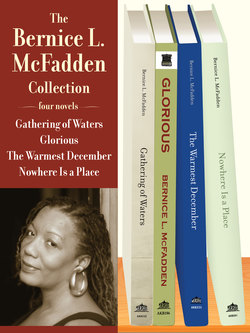

Читать книгу The Bernice L. McFadden Collection - Bernice L. McFadden - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Seven

Iess than a year after they were married, Doll gave birth to a girl who they named Hemmingway. A boy followed three years later, and they named him Paris.

Doll didn’t make a good wife or a good mother.

She did not allow her children to call her Mama or Mommy—“You call me Dolly. Doll-lee!”

She did not cuddle, tend to runny noses, or wrap their necks with woolen scarves to protect them from the cold. She may have fawned and fussed in public— but in the privacy of their home Doll avoided the children with the same vigor she used to evade housework.

For the most part, her days were spent lounging in her slip, sipping sweet tea, listening to George Tory and Skip Blake albums on the phonograph. The only reason she even attended church service was because she enjoyed the arresting effect her presence had on the congregation.

Besides all of that, one of the only other things she enjoyed doing was making johnnycakes. Even those people who did not like her had to admit that Doll’s johnnycakes were the best they’d ever tasted. Light, fluffy, heaven-on-your-tongue, melt-in-your-mouth type of good. So good it almost made her behavior acceptable.

Almost.

* * *

One evening, August bid Doll and the children goodbye and set off with two ministers to host a midnight revival.

“I’ll be back by sunup,” he said as he mounted his horse.

Doll shrugged, “Okay.”

In the darkest part of the night, Hemmingway awoke to Paris’s wailing. She climbed from her bed, went to his crib, and stuck her finger in his diaper. It was wet.

Hemmingway walked confidently down the hallway toward her parents’ bedroom. Unlike most children, she was not afraid of the dark. Upon reaching the bedroom door, she rapped softly on it while calling, “Dolly? Dolly?”

There was no answer, so Hemmingway turned the knob and pushed.

“Dolly?”

The room was cast in shadows. She could see the gray silhouette of her mother’s body stretched out on the bed.

“Dolly, Paris is wet and I think he’s hungry too.”

The silhouette shifted and the bedsheets rustled. A voice the girl had never heard before said, “Hemmingway, is that you? Come in here, sweetness.”

Can a voice have fingers? That one did. Icy fingers that closed around Hemmingway’s young heart.

The darkness shifted and the silhouette sat up. “Come here,” it cackled.

Hemmingway backed out of the room, ran down the hallway and into her bedroom. She dragged the painted wooden rocking horse across the floor and pushed it up against the closed door.

Paris was screaming by then, but his sister barely noticed above the sound of her galloping heart. The baby screamed himself hoarse and finally fell asleep. Hemmingway remained awake, watching the door and listening for the voice with the icy fingers. She did not know when sleep stole her away, but she would always remember the dream that followed of her and Paris running for their lives through a dark, lush forest. On their heels was a wolf wearing the face of their mother.

The next morning Hemmingway woke to find Paris gone. Fearing that the wolf in her dreams had taken him, she leapt from the bed and crept out of the room. The air in the house was soaked with the scent of bacon, eggs, grits, and johnnycakes. She could hear her father’s voice chiming merrily in the kitchen.

Doll was seated at the table, nursing Paris. When she looked up and saw Hemmingway standing in the doorway, her face turned bright with pleasure.

“Morning, darling, how did you sleep?”

“Hey, baby,” August smiled.

Hemmingway watched them. Not sure yet if this was part of her nightmare, she remained in the doorway.

“Oh, we’re not speaking this morning?” Doll sang.

August frowned. “What’s wrong with you?”

The girl took a tentative step into the bright light that streamed through the kitchen windows. “Daddy?”

“Yes?”

Hemmingway flew into him and nuzzled her nose deep into his neck. He smelled like night air, liniment, and scorched cedar chips.

He was real. It was not a dream.

August patted Hemmingway’s back and shot Doll a questioning look. Doll shrugged her shoulders and pried Paris’s lips from her nipple.

“Baby,” August crooned as he tried to peel Hemmingway off of him, “what in the world is wrong with you today?”

“Oh, August, stop babying that girl,” Doll admonished. “You’ve got her spoiled rotten!” Doll rose from her seat, propped Paris on her hip, and addressed Hemmingway. “I made you some oatmeal. It’s in the bowl over there on the stove. Come on now, let go of your father.”

Hemmingway held fast.

“Sweetheart, what’s wrong?” August gently pushed Hemmingway off of him and began to examine her. He took her face into his hands, glided his fingers down her arms. “Are you hurt?”

“Who would hurt her, August?” Doll snapped. “I’ll tell you what’s wrong with her, she likes too much attention, that’s what!”

Hemmingway slipped from her father’s lap.

“August, you need to wash up and get to bed. You look whipped.”

He nodded dutifully, but his eyes were still resting on Hemmingway’s face. “You’re okay, right?”

She glanced at Doll, who was glowering at her. “Yes, Daddy, I’m fine,” she whispered.

“Good.” August gave his daughter a tender pat on her head and walked out of the kitchen.

“Take care of them dishes when you’re done,” Doll ordered as she followed August out.

Hemmingway didn’t move to retrieve the bowl of hot cereal until the slapping sound of Doll’s house slippers had faded away. At the table, she spooned up a large helping of the cereal and brought it to her open mouth.

Good thing she smelled the turpentine before she ate it, or this story might have ended here.