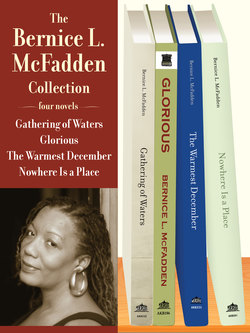

Читать книгу The Bernice L. McFadden Collection - Bernice L. McFadden - Страница 25

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Sixteen

On Candle Street Cole Payne was in bed, propped up on four silk pillows, watching Doll dance around the room naked, save for the wet yellow scarf she wore tied around her midsection.

He’d moved the phonograph from the drawing room into the bedroom and Doll had placed the well-worn Muggsy Spanier record “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate” on the turntable and was raunchily swaying her hips.

It was the first time the two had had sex in his marriage bed. Before that, they’d ravished each other in the cellar on a stack of croker sacks, and up against the walls of the shed. Once they did it in the drawing room, on the couch, while Melinda slept in the bedroom above them.

The song ended and Doll took a bow. Cole sat up and applauded. “More, more!” he cried jubilantly.

Doll happily obliged, replacing Spanier with King Oliver. She lowered the needle onto the vinyl and King Oliver began to blare: Ev-’ry bod-y gets the blues now and then, and don’t know what to do. I’ve had it hap-pen man-y, man-y times to me, and so have you …

Doll rolled her shoulders and sang along. Cole grinned and reached for the cigar that was smoldering in the ashtray on the nightstand.

“I like that song,” Cole said. “What’s it called?”

Doll crossed the floor in sleek, long strides. “‘Doctor Jazz,’” she purred.

After Paris left for church, Hemmingway headed out of the house, across the bridge, and down Candle Street in search of Doll. What Hemmingway would do if she found her hadn’t quite come together yet.

The street was empty, but Hemmingway could feel curious eyes watching her from behind heavy-curtained windows. Halfway down Candle, the wind snatched the umbrella out of her hands, blew it across the road and into the river. Within seconds, she was drenched.

Deflated, Hemmingway started back toward the bridge. As she passed Cole Payne’s house, she thought she heard King Oliver’s rippling voice exclaiming, The more I get, the more I want, it seems …

She knew that song well, because Doll played it endlessly. Hemmingway stopped and strained to hear above the roar of the rain. Soon Oliver’s famous horn splintered the din and Hemmingway followed the melody straight to Cole Payne’s front door.

Just as the weather turned sinister, August took his place behind the pulpit. He was so surprised to see Mingo Bailey, soaked through and shivering in the third pew, that he nodded in his direction and bellowed, “Welcome, Brother Mingo!”

Paris alone was seated in the front pew. August shot him a questioning glance, and the boy shrugged his shoulders in response.

August’s mind screamed: Probably with that man!

Probably, August concurred with himself inwardly. But where’s Hemmingway?

“Let us bow our heads and pray. Dear Father …”

Outside, the thunder clapped so loudly that the parishioners shrieked and grabbed hold of one another.

After the opening prayer, August turned to the choir. “Choir,” he prompted, and the men and women burst into song.

The wind roared in protest, and August raised his arms high above his head and commanded, “Sing louder!”

Upstairs, in one of the numerous bedrooms of the Payne residence, a window banged open, shattering the glass. Cole jumped from the bed and darted from one room to the next until he came upon the mess. Rain, fueled by the wind, spewed in through the broken window and pooled on the floor.

At the church, someone looked down and saw that water was rising up through the seams of the floorboards. Another member spied it seeping in from beneath the door.

The choir continued to sing.

Outside, the wind raced around the church growling and snorting. The congregation rippled with fear.

“Stay calm, flock! Stay calm,” August warned.

Downstairs at the Payne home, Hemmingway was banging furiously on the back door when the upstairs window exploded and rained down shards of glass onto her head. Panic-stricken, she snatched up a nearby flowerpot, launched it through the window of the door, snaked her hand through the ragged opening, and turned the lock.

Upstairs, Cole walked back into the room. “It’s getting really nasty out there.”

Doll was in the bed, stretched out on her back, admiring her fingernails. “What?”

Cole was about to repeat himself, when he heard the clatter of glass downstairs.

“What now?” he muttered as he took up one of the three oil lamps and fled from the room. With the lamplight illuminating his way, Cole bounded down the stairs.

When Hemmingway saw the beam, she hurried toward the light, hands flailing.

Cole’s heart shuddered as he spotted the dark figure racing toward him. “Who’s that!” he yelled, raising the lamp high into the air.

“Hemmingway Hilson!”

Cole stalled and lowered the lamp. “Who?”

From above him, Doll called out, “Oh, that’s the reverend’s daughter.”

Both Cole and Hemmingway looked up to see Doll leaning girlishly over the banister, her bare breast swinging like church bells.

So here is the evidence, Hemmingway thought to herself as her eyes moved from Doll to Cole and then back to Doll. “You roach!” she screamed, and took flight.

Upriver the levees gave way, and the Mississippi and all of her arteries breached their shores. The surge moved like a beast downriver, smashing through the wall of the church and toppling all but two homes on Nigger Row.

On Candle Street, Cole fought to separate mother and daughter as they clawed one another, and so none heard the growl of the approaching heave of water until it plowed through the front door. They scrambled up the stairs to safety, and stood mesmerized with horror as the water magically transformed the foyer into a pool.

Not one amongst them could swim.

“We need to go up to the attic, now!” Cole yelled.

Within seconds the lower half of the staircase was completely submerged.

Feeling scared and powerless, Hemmingway did what any child would have done in that situation: “Mommy,” she said, and reached for Doll’s hand.

Doll Hilson looked down at her daughter’s hand and began to laugh. If Hemmingway had any bit of hope that she could ever love her mother, Doll’s refusal to take her hand dashed it all away.

The house lurched; Doll swayed and shrieked with terror as she grappled to clamp hold of the very hand she’d just rejected.

Hemmingway swiftly pulled her hand from Doll’s reach.

“Help me!”

The house pitched again, the staircase buckled, and Doll went reeling down into water.

Cole was stunned mute and rendered immobile. Only his eyes continued to work, swinging unbelievingly between the placid indifference on Hemmingway’s face and the thrashing Doll who was struggling for her life.

“Hemmingway!” Doll gurgled as the swirling water pulled her under. “Hemm—”

Hemmingway didn’t move. Cole couldn’t move.

Doll’s head disappeared beneath the water, resurfaced, and then disappeared again. Soon after, Esther’s spirit floated up toward the ceiling and perched on the chandelier.

The next day, the sky spread itself across Mississippi in a serene blanket of baby blue. And after months of obscurity, the sun returned, white bright and hot.