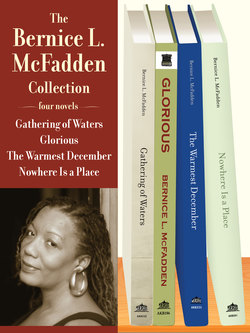

Читать книгу The Bernice L. McFadden Collection - Bernice L. McFadden - Страница 27

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Eighteen

Eula Milam was a short, rotund woman with large dark eyes. She wore her wavy black hair pinned in a loose bun atop her head. She arrived at the Williams and Lord funeral home flanked by her son Fleming and Vance Manning. Mr. Lord led them into a large room with walls covered in bright white tile in the shape of playing cards. The room was filled with more than a dozen bodies and at the sight of so much death, Eula’s legs turned to rubber.

“He’s just over here,” Mr. Lord said.

Vance and Fleming hooked their hands under Eula’s arms and guided her toward her son.

“He look like he’s asleep,” Eula whispered. She wrung her hands and wailed, “Oh, my boy. My sweet, sweet boy!”

In a moment of dramatic grief, Eula Milam threw herself onto J.W.; the weight of her body caused the chairs to shoot out from beneath J.W. and both mother and dead son crashed down onto the melting block of ice. The pennies went skidding across the floor and fell into the drain.

Fleming ran screaming from the room, while Vance and Mr. Lord stood watching in stunned silence as Eula flopped around like a fish on land.

Eula grabbed hold of J.W.’s hand and cried, “Oh, God, why, why!”

The men took her meaty arms and tried to pull her upright, but she remained sprawled on the floor, clinging for life to her son.

“Please, Mrs. Milam, please,” Mr. Lord begged.

“Goddammit, Eula, turn that boy loose!” Vance ordered.

“Ouch, Mama, lemme go!”

Mr. Lord stared at Vance and Vance returned the man’s perplexed gaze. They both peered down at Eula, whose eyes were fixed on J.W.’s heaving chest.

Now, you may doubt that this actually happened. But I have no reason to lie to you. People coming back from the dead is a phenomenon that can be traced all the way back to the Old Testament of the Bible. Just the other day I became aware of a sixty-year-old woman who was hospitalized for an unexplained illness. In the night, her heart stopped beating and the physician pronounced her dead. She was taken to the morgue and her children were called. When the children arrived to identify the body, the old woman’s eyes popped open and she began to cough.

Across the world in Nigeria, a Muslim woman died in childbirth and within twenty-four hours, her still body was bathed, wrapped in white muslin cloth, turned onto its side, and placed in the ground. As the mourners recited the Quranic verse and poured handfuls of soil into the grave, the woman flipped over, sat up, and began clawing at the shroud she had been encased in.

Medical officials blame the occurrence on human error. They even have a term for it: Lazarus syndrome. The religious, of course, give the glory to God. However, the culprit in the resurrection of J.W. Milam was none other than Esther.

Days later the waters started to recede, and the dead began to thoroughly reveal themselves.

Floating bodies. Bodies in trees, trapped in houses. Bodies attached to hands thrust like flagpoles from mountains of mud.

Even the undertaker, who had made a career of dealing with the dead and their survivors, became overwhelmed with grief and broke down in tears.

For the ones who could be coffined, there were funerals. August, Doll, and Paris were laid to rest alongside one another.

The missing and unaccounted for were memorialized. Melinda Payne and her faithful servant Caress fell under that category.

For years Cole would grieve and torture himself for three things he had no control over: his love-struck heart, the flood, and Doll’s death.

Hemmingway had her cross to bear as well. She had watched Doll die. Had in fact had a hand in her death. At the funeral she looked calmly into her mother’s dead, bloated face, and afterward she stood watching as the gravediggers covered the coffin with dirt. Even so, she was not confident that Doll was really dead, and she would live the rest of her days glancing over her shoulder expecting to see Doll: teeth bared, clutching a butcher knife, charging toward her. Or worse yet—Doll smiling, face lit up with her arms fanned out in anticipation of a hug.

***

It took three months of repair before the house on Candle Street was made livable again. Workers attacked the water-damaged walls with hammers, picks, and chisels, chopping away plaster and wooden laths until they reached the joists and studs. Those they dissembled, removed, and replaced with new ones. Rock laths were nailed onto the studs and three layers of gypsum plaster were smoothed on and left to dry.

The oak floors, staircase, and the veranda were all removed and replaced. New furniture, icebox, and stove were purchased and installed.

By Independence Day, that house on Candle Street looked brand new beneath the burst of the brilliant red, white, and blue fireworks.

Hemmingway became his new maid, not for any reason other than the simple fact that she was an orphan and he, a widower—so all they had were each other.

For a while she lived in the room that Caress had once occupied. Well, Caress still owned that space, and occasionally made her presence known by throwing her ghostly weight against the walls and rattling the frosted light fixtures.

It didn’t bother Hemmingway in the least. She had spent the first half of her life battling the dark spirit that was her mother, and so if Caress were trying to unnerve her, she would have to step up her efforts.

Sometimes she would go to the bridge and stare across at what once was. Birds and squirrels had taken up residence in the two remaining homes on Nigger Row. In three more years, March winds would level the houses and tall grass would grow up and around the rubble.

Widower and orphan led a quiet life. Hemmingway kept the house spotless, his clothes clean, and his belly full.

One Sunday she recreated Doll’s johnnycakes. When she placed the plate before him, Cole began to weep and the rain of tears drenched the cakes, turning them back into lumps of sweet, sticky dough.