Читать книгу In Winter's Kitchen - Beth Dooley - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

DO YOU KNOW WHERE YOU ARE?

In late summer of 1979, my husband, Kevin, and I loaded a U-Haul in Princeton, New Jersey, and headed to Minneapolis. “Why?” friends wondered. Didn’t we already have plenty of great prospects in our hometowns? What about our families, the bustling New York metro? They could understand Los Angeles or Chicago, sure, but “Mindianaolopis,” as my dad called it, was flyover country, land of interminable winters and a lot of corn. Kevin, a fresh-out-of-law-school attorney, was drawn to the Twin Cities’ vibrant business economy and lack of big-city commute. And we were both attracted to Minnesota’s lakes and trails, the piney woods and big rivers. I had already left my job with a large New York publishing firm to take on freelance writing assignments, work I could do anywhere.

So, like generations of women before me, I went west with the man I loved to create a new life and make a home. I’d loaded up our starter furniture and wedding gifts as well as my grandmother’s worn bread trencher and dented copper bowl, familiar tools of my past that seemed essential to my future.

In my beloved grandmother’s kitchen, with its chipped blue cabinets, rolling wooden floor, and smells of coffee, oatmeal, and cooling pies, I’d learned to knead bread dough until it was soft as a baby’s bottom and simmer raspberries into jam thick enough to coat the back of a spoon. When I was small, we’d drive Route 35 to her home on the Jersey Shore and at each farm stand she’d chat with Dolores, Bonnie, or Joyce; sniff peaches; thump melons; and check the princess corn, pulling back a few leaves to inspect its pearly kernels. While she shared recipes clipped from the Newark Star-Ledger, I’d toe at the dirt with my sneaker, pet a scruffy dog, and lug the basket back to her blue Cadillac, seats sticky from heat. My reward was a sun-warmed peach so ripe its juice dribbled down my arm. When finally we crunched over the stones in her driveway and stepped into the soft briny air, our evening hungers surged. She’d sizzle meat patties from Arctic Meat in the black cast-iron skillet and steam Spike’s Fish Market’s blue crabs in the red enamel pot; I’d peel the fuzzy fruit to top with sweet cream delivered to her back door by Jeff of Borden. Every ingredient came from a person and place with a name. Just before sitting down, I’d carefully slice those blowsy, delicate Jersey tomatoes into fat wheels: tomatoes that remain, for me, the taste of summer itself.

The year before we moved, I’d been writing for the weekly Princeton Packet, covering home and garden features like the Baptist church’s hundred-year anniversary potluck, as well as the beat no one wanted, the Planning and Zoning Board meetings. These civic gatherings, focused on land-use issues—water drainage, setbacks, building codes—were long, contentious, and fascinating. Residents fought to hold development at bay in an effort to save lush farmland while the real-estate lawyers, with flip charts and projections, promised increased tax revenues, new schools, and community centers. I watched as, quick as a cold snap in autumn, the bucolic landscape gave way to malls and condos for New York and Philadelphia commuters. By the time we left Princeton, the farm stands along Route 35 were gone. To find a Jersey tomato you’d have to grow your own.

As we fit the last box into the trailer, delaying our goodbyes, I offered to host Thanksgiving. My dad’s favorite holiday involved our extended family and assorted friends and, for as long as I could remember, had been held in my parents’ home. But Dad squared his shoulders and gamely said, “Sure. Why not?” When he promised to fly everyone out, I sighed in relief and excitement. I had a date and a focus to frame this adventure, a purpose and deadline by which to get my turkeys in a row; Thanksgiving would be my guide star to a new place.

Kevin and I barreled into the land of the “Jolly, ho ho ho . . . Green Giant” with a bouncy, week-old brown Labrador pup, Hershey. Through Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, acres of monotonous neon-green corn rolled by. These large tracts looked nothing like the uneven patchwork of crops on the small farms in NJ. In fact, what was growing here was not edible corn but the ingredients for sodas and food products. Where were the people? Where was the food? We pulled off the highway in search of a diner, and drove along ghostly main streets of empty storefronts, anchored by gas-station convenience stores. The only produce—apples individually wrapped in plastic, bruised bananas, and shriveled oranges—was tucked on a back corner shelf. White-bread sandwiches in clamshells and hot dogs spinning on heated rollers: all looked pretty grim.

Eventually, as we cleared Madison, the countryside began to soften to more natural shades of gold and pale green, and we wound up I-94 through central Wisconsin’s rolling fields, under wide skies and tumbling clouds. Cattle grazed on greening pastures and horses wandered near big red barns. When we finally crossed the St. Croix River into Minnesota, my heart, opened by such expanse, was humble and hopeful.

Soon as we unpacked the last box in the lower level of our Minneapolis duplex rental, we met up with a classmate of Kevin’s at Becky’s Cafeteria for what he called the “true Minnesota lunch.” On the corner of Hennepin Avenue, one of the city’s main arteries, Becky’s was a huge, dim space of velvet curtains and soft organ music. On a table near the cafeteria line, a Bible was opened to Jeremiah, chapter 31, for casual reading. Becky’s offered a “four-square” selection cucumber and sour cream salad (eighteen cents), beef loaf (seventy-two cents), potato hash (thirty-five cents), and a slab of Jell-O, plus warm, soft potato rolls just out of the oven and apple pie with a crust so rumpled and uneven, it had to have been homemade. Every seat was taken—by bearded students, business suits, blue-haired women. The meal was honest, but I had to wonder: Do people here really eat swampy broccoli, iceberg lettuce, and fried chicken for lunch everyday? Not far from our home, the Red Owl grocery stocked disappointing soft apples and wimpy carrots, aisles of frozen dinners and shelves of packaged mac and cheese. We had landed in “the nation’s breadbasket” only to find it filled with tasteless white bread.

But on a tip from our neighbor Bettye, a chatty retired teacher who had delivered a batch of fresh blueberry muffins to our front door, I ventured off one Saturday morning to find the Minneapolis Farmers’ Market. There, I was swept into a whirlwind of colors and aromas—brilliant red tomatoes, glossy eggplants, crimson crab apples, wrinkled tiny hot peppers—aromas of damp earth, wet wool, coffee, sweat, and sweet cider—jolly laughter and shouts in languages I couldn’t understand. I stopped at a mound of orange carrots with frilly green tops and handed a dollar to the grower, Eugene Kroger, for a bundle of roots that resembled his gnarled fingers. He rubbed off a little bit of dirt and gave me a carrot to taste. With a delicious crunch, and for a bittersweet moment, I tumbled back to my grandmother and those New Jersey farm stands.

Registering my delight, Kroger smiled. “These are plenty fresh, I picked them at 4:00 a.m. this morning,” he said, and bit into a carrot, too. This exchange between cook and farmer is as familiar to me as my childhood and as ancient as civilization.

So began a Saturday ritual and unlikely friendship between this rugged back-to-the-lander and me, the curious ingénue, connected through our love of sweet carrots. I’d bring him a coffee and he’d slip me an extra carton of raspberries or a melon or two. This Vietnam vet, missing a leg, did not look as though life had pummeled him into the ground. “Working the land,” he said, “I figured it out.” On Saturday mornings, I rose early and left our quiet house, drawn to the jostling, shouting, and tasting, the aromatic life that brimmed in those stalls. Each week served up a surprise as the season built to the crescendo of harvest. Gritty and colorful, chaotic and coded, the market was seductively real. Through the months, I began to get a sense of this place, its food, and the people who grew it and bought it. And I knew that here, in the market, I might find the life I wanted, guided by memories of those I loved and all that I’d left behind.

The farmers’ market was more than the source of a week’s fresh produce; it was a wellspring of inspiration, a weekly calendar of the land’s bounty. There, I also met Pakou Hang, an energetic Hmong teenager who explained how to steep fragrant lemongrass in soup, toss Thai basil in salads of chicken and beef, and roast and mash her farm’s ruddy sweet potatoes with fish sauce. As she dug into the cash box to make change, she’d translate my questions for her grandmother, who sat in a lawn chair next to the family’s van. The grandmother answered in Hmong, smiling and gesturing with her hands, chopping vegetables, stirring a pot, and warning me about her fiery leghorn peppers, named for a chicken’s ankle. As I carried home my market basket of bok choy and bitter melon, Kroger’s carrots and tiny strawberries, I could almost feel my grandmother’s hand in mine.

My mom had slipped her copy of The Joy of Cooking into one of our moving boxes and when I unpacked this unexpected gift it greeted me like an old friend. As a teenager I’d tucked it into my book bag to read like a novel when I should have been studying. All through college, when I’d felt lost or homesick, I’d turned to cookbooks to soothe and entertain.

And cookbooks, too, had introduced me to agriculture’s environmental issues back when I had been a graduate student living in a shared house, cooking with friends. Diet for a Small Planet and The Moosewood Cookbook had been our Bibles of food awakening. Fueled by nicotine and cheap wine, we’d lingered for hours at our table, an old door propped on cinder-block legs, discussing farm issues and claiming “the personal is political”—talking over Cesar Chavez and workers’ rights, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, the dangers of Alar and DDT.

So, as I sat at the table my brother had built for our first Minneapolis kitchen, turning those sticky, dog-eared pages, I began to feel more at home. Beneath a cookbook’s lists of ingredients and steps to follow lie tales as rich and deep as any to be found in fiction. They are forays into families’ homes and glimpses into far-off lands redolent of garlic and rosemary, saffron and cardamom. Recipes are stories with happy endings, of being sated and cared for in a way that feels gentle. I’d even suggest that the intentions of a cookbook author are the same as those of a novelist: to use both creativity and format to transmit an experience to the reader. As I revisited the old Joy, I realized I wanted to learn this language and translate the sounds, scents, and tastes of cooking onto the page, just as a composer writes out a score. I’ve always been happiest in the kitchen—chopping, sizzling, stirring—creating beautiful, flavorful food that nourishes and delights. As a reader of cookbooks, I loved the instructions that helped me imagine a meal. I wanted to know how to document such steps to pleasure, to both capture and share them. And I hoped such work would guide my search for the hearth, the heart of the home.

Despite all my reading, however, I had never stepped into a farmer’s field. At the Minneapolis market, I could finally get answers directly from working growers about what it takes to cultivate delicious, bright-green lettuce and why the local varieties I used in my salad cost more than the pale heads sold in grocery stores. I began to understand local food.

Innocent and ambitious, I wanted to share with my family these new discoveries when they arrived in town. Hosting Thanksgiving for the first time is a rite of passage for any cook. Like that first bike ride without training wheels, it is both daunting and liberating. I got to choose which traditional foods to serve and which to scratch. I wanted to showcase those carrots—as well as ruffled kale, cranberries, sweet potatoes, and a small free-range turkey—and I wanted to make all the pies, bake all the bread, and create all the condiments by myself.

We didn’t have a single table big enough to seat everyone, so I simply duct-taped together three different tables and smoothed my grandmother’s lace tablecloth over the odd assembly. My dad told me over the phone that he’d ordered special cheese to be delivered and that he planned to bring the “good carving knife.” I could picture this bone-handled beauty, snuggled in its velvet-lined, rosewood case and folded into his suitcase for a trip into an unknown place so far from my family’s comfortable home.

It’s not that our traditional Thanksgiving fare was all that special. Sometimes the gravy was gloppy or the turkey dry. But in my parents’ sprawling dining room we’d always played out our vision of what a family might be if we didn’t have to live with each other all the time. No uncle’s divorce, no cousin’s odd girlfriend, not even differing views on the Vietnam War could spoil the fun. We were open, joyful. The lights of Thanksgiving past would glow warmly as my father held court at the head of the table. Having sliced the breast meat to the bone with exquisite thinness, he would raise his glass to toast the guests and the bounty before us. More than any other day, Thanksgiving brought out the essential nature of my dad. He showed us that one could live both loud and gentle, both hungry and whole.

So now, with that Joy of Cooking spine cracked flat open on the counter, I rolled pie dough, kneaded bread, and scored and roasted chestnuts for stuffing. I scrubbed the counters and floors, ironed napkins, polished silver, and, as fatigue set in, began to wonder why I’d thought this was such a great idea.

The night my family flew in, the Twin Cities were hit with the season’s first storm of wet, sloppy snow. My family was delayed several hours in Chicago and it was near midnight by the time I picked them up. The driving had been slow, the roads treacherous.

After heartfelt airport hugs, all six of us, sitting on luggage, squeezed into my Datsun and crept onto the highway. Icy clumps pummeled the roof and glazed the windshield, making it difficult to see as freight trucks barreled by. The giddiness of our reunion soon congealed into uncomfortable silence. I missed our exit, circled up over the highway, and retraced our route, not once but twice, and on the third try, as we passed the grain silos on Hiawatha Avenue . . . my father could hold back no longer and asked me in a whisper, thin with impatience, “Beth, do you know where you are?”

What I knew was that change is hard. But while I realized that this was going to be a different Thanksgiving in location as well as food, I was naively unprepared for its emotional impact. Applying my grandmother’s early lessons and my understanding of Rachel Carson to the fresh, beautiful food from my new local market just wasn’t playing out quite as planned. I had a lot to learn.

Thanksgiving morning my mother, looking askance, asked, “No creamed onions?” Even though none of us had ever actually eaten the Birds Eye Pearl Onions in a Real Cream Sauce, they were my absent Aunt Ruth’s favorite. Aunt Ruth adored fake pearls and Scotch and doused herself in Shalimar, and though she was not present, the missing onions seemed like a slight.

“Where’s the big bird?” my dad asked as I trussed the local, organic, free-range, but admittedly undersized turkey. My brother, digging a bag of Cheetos from his backpack, paused long enough to say, “Looks like Beth went with a fat chicken instead.” In our tiny living room, sibling rivalries, unspoken resentments, and secret rages, fueled by the exhaustion of holiday travel, threatened to boil over. “Oh God! Not more weeds and seeds,” moaned my sister as I trimmed the kale. “Eeew,” she said, spotting the yogurt curing on top of the fridge. “Stinky milk!”

My hopes for fluffy mashed potatoes were dashed, for I’d chosen the wrong spuds—waxy yellow Finn and red bliss—a mistake compounded when I tried to whip them up in the food processor and churned out a gluey and gray mass. That little turkey had a teeny lean breast but huge thighs and might have provided delicious dark meat, if it hadn’t been overcooked (no pop-up thermometer).

The kale, however, was a surprising hit, thanks to my friend Atina’s advice to sauté it with garlic and douse it with dark sesame oil. (“Cooked that way, even gravel tastes good,” she quipped.) The gnarled sweet potatoes were wonderfully and naturally brown-sugar sweet, and the Haralson apples for pie were tart, juicy, and crisp. As we peeled and sliced them my mom asked me to ship a box back east. My valiant failures had elicited sympathies and inspired engagement as my brothers and sisters chipped in to help with the meal. Being in the kitchen knitted us together in ways we didn’t know we’d forgotten.

At the rickety makeshift tables, my dad did the best he could to carve the little turkey with the beautiful knife he had bequeathed us. We lit candles as the day darkened and the mood shifted. In the making and partaking of this dinner we’d renewed our relationships, to each other and to a different tradition.

Though my father is long gone now, that knife still helps me cut through all my doubts about the importance of cooking, of gathering in the kitchen engaged in simple, joyful tasks. Sharing time, working with our hands, and chatting keeps these traditions relevant, no matter the distance and differences.

Thanksgiving is the finale for the farmers at market, and on Black Friday, Christmas-tree vendors take over the stalls. But my journey into this place, Minnesota, through its food and its people, had just begun.

I discovered the Wedge Community Co-op, just a block from our home, one of the country’s first. In the early 1970s, the People’s Pantry, a food-buying club located on a University of Minnesota professor’s back porch, had grown into a neighborhood co-op that inspired the area’s next thirteen independent member-owned stores. Organized around “cooperative principles” of education, sustainability, and fair wages, they became centers of food advocacy. I was drawn to the produce, the brightest and freshest available, as well as the information the Wedge provided. Everything on the racks was labeled with its source as well as how it was grown—conventional, transitional, organic. The Wedge’s newsletter and its flyers addressed every concern.

To work off my forty-dollar lifetime membership, I stacked organic apples and spritzed lettuce on early Saturday mornings, and learned from Edward Brown, produce manager, about his innovative financial agreements with farmers. Brown would guarantee a price for carrots or apples in advance of the growing season instead of looking for the lowest price posted by distributors each week. Sometimes this worked in the Wedge’s favor, as when there was a shortage of an item and prices soared. In other instances, the farmer got a bonus, if the Wedge had promised more than current market price. Volunteering at the Wedge was like taking a course in food policy as well as ones in nutrition, cooking, and environmental studies. Mark Ritchie, former Minnesota secretary of state, once said, “Anyone in DFL [Democratic-Farmer-Labor] politics probably got their start at a co-op.” For me, the Wedge was a source of more than good-tasting carrots and bulk oatmeal.

I’d found a job with a large advertising agency, writing promotional copy and brochures for food companies (Land O’Lakes, Jerome Foods, and Snoboy produce). I had wanted to write about food for a living and while this was not the kind of food I’d anticipated covering, it was the closest I could get at the time. I hoped the professional experience might fill out my short résumé and lead me to the kind of work I yearned to do. On weekends, I was at the Wedge or cooking for an ever-widening circle of friends. In those years, with no kids, I had endless hours to plan and shop for dinners of osso buco, potatoes Anna, tarte tatin, and homemade bread. And it seemed—in Minneapolis, anyway—that a good invitation was often returned in kind.

One evening, at a formal affair in a tony Kenwood mansion, I was dreading a meal of catered overcooked chicken. So I could hardly contain my delight when we were served honest home cooking: rosemary lamb stew with olives and buttered noodles, simple green salad in mustardy dressing, and a runny Wisconsin cheese with tart chutney and baguette, all followed by dark-chocolate truffles.

To my happy surprise, my tablemates, Meg Anderson and David Washburn, did not want to talk about the Senate race or the theater. Instead, they shared with me their newest project, an organic farm, Red Cardinal, the first community supported agriculture (CSA) in the state.

In answer to my rapid-fire questions, Washburn patiently explained diversified crop rotation, pest-eating ladybugs that replaced pesticides, and intensive composting practices in lieu of chemical fertilizers. He relayed the intricate calculations made to plant crops so that each week’s delivery contained an interesting assortment for the member’s boxed shares. Before I sipped the last drop of champagne, I’d written a check for a piece of the farm.

Washburn had just sold a chain of successful fitness studios and was no stranger to the challenge of starting a membership-based business. Anderson had left her job as a buyer for a department store. The couple, backed by family resources, was committing their entrepreneurial and artistic talents to this new endeavor. Neither Anderson nor Washburn came from a farming background, but their knowledge of health and wellness, the environment, and social justice issues ignited their mission. Plus Anderson, a master gardener, could now devote more time to growing her grandfather’s heirloom peonies for sale to restaurants and shops.

The third partner, Everett Meyers, grew up on the farm next door to Red Cardinal and was working as an agricultural technical trainer for the Peace Corps in Ecuador. He’d envisioned starting a farm on his family’s land when he returned home, and so brought to the partnership an experience with small-scale agriculture and a knowledge of the land that became crucial to Red Cardinal’s success.

That first season the pick-up days at a neighbor’s home became the social highlight in our week. By that time, Kevin and I had three young boys—Matt, Kip, and Tim—who tumbled on the front lawn while we chatted with Anderson and Washburn about how an early thaw had hurt the raspberry crop, why a cold snap had helped sweeten the brussels sprouts, and what to do with those tomatillos and kohlrabies. Every box was beautifully arranged with Anderson’s artistic eye—tiny yellow pear tomatoes ringed with baby bok choy, garlic scapes nestled beside potatoes the size of my thumb. On our drives home, an uncommon sibling truce reigned in the backseat as the boys munched on carrots and fished for raspberries straight from the box.

On CSA workdays, we’d leave our own garden and housework and head to the country to plant, weed, and harvest. For lunch, Anderson would cook up stir-fries, salads, and bean dishes for us volunteer workers and the fifteen farmhands. Among those farmhands were a law-school applicant, a retired food-company executive, a FedEx office manager changing careers, a young couple hoping to start their own farm, and immigrants from Guatemala and Cambodia. When they’d finished their meal, the crew would lie under the trees, hats covering their eyes after a day that had begun at 4:00 a.m.; all were content. No masks needed to protect them from pesticide fumes, no rubber overalls to guard against fertilizer, no huge tractors in sight. Come sunset, we’d kick back for a potluck and sing folk songs accompanied by the strumming of a beat-up guitar.

One afternoon, standing among Anderson’s peonies, looking over the rows of kale, the sprouting carrots, and the sprawling zucchini, I sensed my place in this web. I took it in, all of it—the pond, the green fields, the pale-pink-and-white flowers, the buzzing bees, even the mosquitoes—and wondered, how can you love a place, how can you fight to protect it, if all it means is loss? Must it all give way? Like the farm stands of New Jersey, must everything give way?

In my day job of writing about frozen cut green beans and turkey cutlets, I’d learned to develop recipes and give context to a dish, skills I applied to the newsletter I created for Red Cardinal’s members. Here I could share news about how many tons of carrots the farm produced, about the gallons of fertilizers and pesticides not sprayed on fields to run off into the Mississippi River, and about the foxes, voles, and eagles that thrived on the land. I wrote about how well-tended, rich soil, full of nutrients, grows the best-tasting, most nutritious food, and passed on Anderson’s cooking tips and recipes.

More than anything else, the CSA changed what and how I cooked. Every week the CSA box was a surprise and often a challenge. I had learned to cook by closely adhering to recipes, much as I learned to play piano by following the strict dictates of my teacher’s sheet music. But now, faced with the wonderfully eclectic and unpredictable weekly share, I began to improvise. I waited. I responded. I relinquished control of my kitchen to the whims of our moody northern climate. Opening that CSA box felt like turning off the radio and walking into the pulse and swing of a live brassy jazz band. And, just like a dancer adapts her steps to the beat of the music, I adapted my cooking to the rhythms of a land that served up so much variety. Finally, conventionality became the exception, not the rule.

Through the past thirty-seven years, as a cook, mom, and cookbook writer, it’s those hours in the kitchen and at our table I cherish most, especially in winter when night presses in and the cold glazes the windows with a lacy sheen. Like so many women who settled in this place of fierce winters and blasting summer, of thrift and bounty, I’ve learned to “neighbor” over coffee, visit with the farmers at market, and listen to the sacred stories of foraging and gathering wild rice. In this region, local food is nothing new.

Our small, independent farmers, processors, and chefs are not romantic innocents. They understand community and honor relationships, work on trust and shun huge bureaucracies. They’ve said “no” to the culture of the suburb and lives of needless convenience. They live where they work, make business decisions for the future, not immediate profit, and their success depends on their physical strength, endurance, and nerve. They contribute to the local economy, provide jobs, pay fair wages, and treat animals humanely while providing us all with delicious, nutritious food.

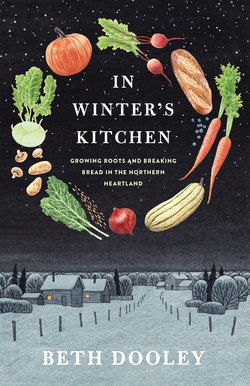

What follows is neither a history nor a cookbook, but a tale of friendships forged while walking the fields and cooking in restaurant kitchens, making cheese and slaughtering chickens, and how these experiences have helped guide me as I’ve tried to live a more meaningful life. And yes, there are recipes, because I hope when you’ve devoured the book you’ll want to cook. Chopping, simmering, stirring, and tasting engage the head and heart. Thus, I’ve also shared stories from my own life with Kevin, raising our sons, of friendships and of family gatherings. The book is stitched together by themes of tradition and heritage, adaptability and resilience, independence and identity, friendship and community, loss and grief and reconciliation, all written with gratitude for people I’ve come to know as well as the gifts of this beautiful earth.

Our Minnesota-born sons will always crave the crisp snap of a Haralson apple and the cold flinty waters of Lake Superior, yet I don’t think I can ever leave behind the taste of a Jersey tomato or the briny, roiling Atlantic. Through the years, as they’ve grown into strong, caring men, we’ve gathered at the table, to joke and to engage in honest conversation about what in our world is not working and how we may become agents of change. And it’s here, with open hearts and honest hungers, we commit with joy and hope, to digging in.