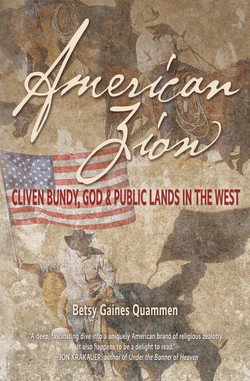

Читать книгу American Zion - Betsy Gaines Quammen - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Seeker

Know ye not that ye are in the hands of God?

—Book of Mormon, Mormon 5:23

Cliven Bundy will tell you that his land war is part of being Mormon, though many Saints would counter his presumption. The church has publicly condemned the family’s claim that their anti-government agitations are justified through Mormon scripture. And this is very important. The Bundy family’s position does not reflect teachings upheld in modern mainstream Mormonism. Yet some of his supporters, including prominent Mormon politicians, do embrace the same convictions that the Bundys espouse. In order to grasp these rationales, we need to go back to the beginnings of the church, this incredibly successful American religion that has a lot to say about proprietorship, rights, and sticking it to the man. We also need to trace how a culture of European and Yankee farmers became irascible cowboys. Then we can better understand Cliven Bundy.

When Cliven’s ancestors arrived in the Great Basin in the late 1840s, finally safe from religious oppression, they made their home in a land most other white settlers had overlooked. They helped build a homeland there, one promised to them by their prophet but which had eluded them before they found it on the flanks of the Wasatch Range. For the Bundy family, their birthrights to this land came with the arrival and the settlement of their forefathers. To make sense of Cliven Bundy and his insurgency is to understand the philosophies, assurances, and prophecies that came from early pioneers devoted to Joseph Smith.

The Bundy family story intrigued me. I’d spent the last decade working with religious leaders on conservation initiatives and I’d not yet had the opportunity to work with Mormons. The church had been slow to issue any formal statement on the environment, and the Bundy family seemed to be using their faith as an argument to deplete the land rather than steward it. I visited the family on March 5, 2015, and left their compound with my own signed Book of Mormon, courtesy of the family patriarch, vowing to Ryan and his father that I would read it. Because Cliven’s convictions were so tied to his religion, I thought this volume would shed light on the underpinnings of the Bundy war. Perhaps as someone raised outside the church, I missed a profundity and poetry that I’ve come to associate with other religious texts, though the Book of Mormon is informative when following Bundy’s motivations. But The Nay Book, a homemade manifesto filled with prophetic quotes by Mormon prophets and warnings about the precarious state of the US Constitution, is even more so. Ryan thumbed through his own copy, one bound in a vinyl binder, during the time I spent with the family. Named for the neighbor who compiled it, Keith Nay, it is often seen in the hands of Bundy’s inner circle at events and gatherings.

Three men came into view the day of my visit, each foundational to the Bundy family position and approach. Nephi Johnson, Cliven’s spiritual great-grandfather. Cleon Skousen, a Mormon right-wing agitator. And of course, Joseph Smith, who built a religion defined by promises of homeland and a personal relationship to God. The first Mormon prophet established a community of people with a history of despising the government, yet a belief in some duty to keep it in check, no matter what this entailed. The world is in its latter days, he warned, which meant time is almost up, coining a “truth” that created, and still creates, an urgency to action. If a stand must be taken, take it now, because there’s no time to lose. With this comes another implication, maybe also contributory to the uprising at Bunkerville, and later at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge: an expectation that a standoff might have a domino effect, leading to larger events that fulfill prophesies outlined in the Book of Revelation, of the story of earth’s destruction and of Christ’s Second Coming.

So let’s begin with Joseph Smith, the first leader of the Latter-day Saints and first Mormon prophet. Many books have been written about Smith, and they range from fawning to condemning. Alex Beam, Fawn Brodie, Richard Lyman Bushman, and even Smith’s own mother, Lucy Mack Smith, told the story of this amazing human, a man who held many in his thrall while outraging and repulsing others. He was incontrovertibly impressive in what he achieved—his church now has over sixteen million members, among whom are the Bundys. And one would be hard-pressed to find a historical figure as curious and as striking as the founder of this ever-flourishing, influential, and inescapably American religion.

Before Joseph was a prophet, as a young man, he was a scryer, a trade that used magical tools in the search for hidden treasure. For his work, he used a device called a seer stone, a dark brown rock he used to seek riches rumored to be buried near his home on the New York frontier. This was a hobby not unusual to his time and place—one based on hearsay and wishful thinking. Stories about buried treasure abounded in upstate New York, where Joseph Smith’s family, for a time, made their home. Tales of pirate Captain Kidd’s gold bullion led hundreds to dig deep trenches in vain. Rumored Spanish and Indian silver called to the farmers in their stony fields, promising riches and escape from the grindingly difficult life of the frontier settler. It certainly called to young Joseph Smith.

In his lifetime, he would meet with unimaginable fame and infamy, leaving behind a legacy that swelled ever greater after his death. But he began his career by digging. The process went more or less like this: First, he would place the stone in the bottom of his hat, then plunge his face into the gloom. In order for the spell to work, all light needed to be occluded so that his stone could “see” treasure, and thereby ascertain its coordinates. But this was only the first of many fiddly steps. Once he determined the location, preparation for excavation began. Perhaps he drew concentric circles around the loot, a ritual his mother would years later write about in her memoir. Pressing circles into the dirt was said to foil supernatural guardians, the ghosts of murdered men charged for eternity to protect these mythic fortunes. Those in the treasure trade warned that phantoms pulled the valuables back deep into the earth if they sensed any threat. Coarse language or the garrulous talk of careless seekers, it was said, could tip the guardians off and cause them to spirit the treasure away.

Smith’s father, Joseph Smith Sr., also a scryer, emphasized the importance of night digs to his son. During the day, he explained, solar warmth coaxed hidden chests with piles of precious objects from the depths of the ground. Best to do most of the work after sunset, when the booty sat just below the earth’s surface. Night digs were thrilling (and booze-soaked) diversions for those living in this time and place, full of ceremony, ritual, and the delicious anticipation of instant wealth. It is easy to imagine that many of the stories of ghosts said to watch over the treasure sites were actually the invention of jumpy drunks startling themselves in the murk of the forest. Strong drink could make the mind rather credulous and prone to exaggeration. Blaming a ghost offered a good excuse for those coming home hammered and empty-handed.

Joseph was born in Vermont in 1805 to parents well-versed in the magic and the supernatural. His father claimed celestial visions and his mother talked regularly to God. This was quite common among folks of this region in nineteenth-century America, a time of great uncertainty and adversity. Having a personal relationship with God and the supernatural provided reassurance in a place where poverty, disease, and desperation abounded. As a boy, Joseph and his family moved from place to place, due to failed crops and burgeoning mortgages. Through difficult though necessary moves, the Smith family, following several failures and subsequent relocations, landed in an environment well-suited to their numinous hobbies. New York State’s “Burned-over District” marinated in a stew of wild revivalism, cults, and extremists preparing adherents for end-times. And it was there Joseph Smith spent his formative years.

In his youth, millennialism was rampant, as were utopian societies promoting everything from sexual libertinism (Oneidans) to abstinence (Shakers). Protestant branches proliferated, especially those offering rebellion against Calvinist notions of predeterminism. In other words, folks did not want to believe that they were fated to either heaven or hell even before they were born. If this were true, then why would one stay upright and honorable rather than spend the days drunk and feckless? If God had already made up His mind, then what was the point of being virtuous? Calvinism left many searching for a faith that would give them some agency, some skin in the game, and the opportunity to be judged for their actions, whether meritorious or sinful. Be it harps and halos or pitchforks and flames, they wanted to feel like they had some ability to determine where they spent their afterlife.

Growing up, Joseph picked through hot embers of the Second Great Awakening, pursuing both buried riches and new versions of Christianity. Although the tray of options was overflowing, he was not satisfied with what was offered. Untrained ministers, aspiring prophets, and self-proclaimed Second Comings roamed the countryside alongside the scryers, all searching to fill that emptiness found both in pockets and souls. Would they discover gold or God? Joseph came of age amid spiritual promiscuity, where, under the drape of a tent, silver-tongued preachers brought their audiences into flailing, juddering, and jerking fits, as if the hand of the Lord himself had reached out and shaken them. So eager were the people for religious novelty, the enthusiasms of upstate New York even brought believers into fits of glossolalia, speaking in tongues known only to God.

This birthplace for so many religious movements provided the incubator for Shakers, Seventh-day Adventists, and Oneidans—sects that encouraged perfectionism. And communalism. And various riffs on hanky-panky. A hundred years after the death of Joseph Smith Jr., writer Fawn Brodie, who grew up in a family with a deep regard for his teachings, described the Burned-over District of upstate New York as a cadre of “the Baptists split into Reformed Baptists, Hard Shell Baptists, Free Will Baptists, Seventh Day Baptists, Footwashers and other sects.” She mentioned Anna Lee, the founder of the Shaker sect who regarded herself as the reincarnation of Christ. And “Isaac Bullard, wearing nothing but a bearskin girdle and his beard, who gathered a following of pilgrims in 1817 in Woodstock, Vermont.” He was a “champion of free love and communism, he regarded washing as a sin and boasted he had not changed his clothes in seven years.” So many wanted to know God. Or to be God. These emerging religious leaders filled a great need, arising in response to a culture yearning for celestial reassurance. Further, if there was ever a place that might inspire someone to imagine his own version of a religion or fancy herself a mystic, the Burned-over District was it, with plenty of muses from which to draw encouragement.

Before upstate New York became a spiritual hotbed, it was homeland to a very different culture. This was the territory of the Seneca nation, one of six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. The five other nations were the Mohawks, Cayugas, Onondagas, Oneidas, and Tuscaroras: descendants of people who had lived here for thousands of years before the British and French came to colonize and spread their own cultural ideas. It should come as no surprise that at this time of white settler revivalism, the Seneca had their own prophet, Handsome Lake, who, after a near-death experience in 1799, began to have religious visions and hold conversations with George Washington and Jesus. Handsome Lake warned his people about the brutal penalties that awaited them if they succumbed to the vices of the settlers. Imbibing whiskey and partaking in gambling, according to Handsome Lake, led to an eternity of drinking molten iron and gaming with scalding cards—consequences of participating in the vices of white people. Like so many other mystics, Handsome Lake spoke of the impending end of the world. Tragically, unlike the Christian preachers’ foretelling of an apocalypse, for the Seneca, Handsome Lake’s prophecies were coming true. As environmental historian Matthew Denis pointed out, the Senecan culture and way of life ended with colonialism, Christian missionizing, and settlement.

In fulfillment of Handsome Lake’s prophecies, settlers continued to arrogate Native land and occasionally, though not surprisingly, those farmers dug up the evidence of the original inhabitants. A projectile point or a shard of pottery, again adding to rumors and expectations of further treasure in the ground. Did the arrowhead indicate a large trove of valuables? Perhaps the riches of a chieftain’s grave or a lost tribe? Farmers pinned their hopes of escaping drudgery and hardship on whispered chitchats of riches cached by the very population that they themselves had impoverished and displaced.

And yet the call of Indian riches rang in the ears of Joseph. As did the dream of an undiscovered conquistador chest of gold. Something precious, buried but undiscovered, waiting for the warmth of the sun and the talents of a true diviner. Yet he found nary a doubloon. Even so, for whatever reason, Joseph enjoyed a good reputation as a scryer during these years—so much so that, in 1825, Josiah Stowell bet on Joseph’s unproven skills and hired him to find a Spanish silver mine rumored to be on his property in Pennsylvania. But after searching and digging and divining and incanting, there was no silver in sight. Angry over this failure, and convinced of Joseph’s chicanery, the farmer’s nephew took Smith to court as a disorderly person and imposter, the first of a lifetime of criminal charges for the soonto-be religious leader.

In spite of this legal tangle, the next chapter in Smith’s life was beginning to come into view. During his time in Pennsylvania, though he didn’t strike it rich, he met his first of many wives, Emma Hale. By then, he’d learned that people eagerly believed in myths, like buried treasure, and in a region of smoldering religious passions, he’d seen a culture’s need for belief as much as their hunger for it. Joseph had met a young Orrin Porter Rockwell, eight years his junior, and their consequential friendship was just budding. Rockwell would help bring Joseph’s religion, as well as a Mormon code of vengeance, into the West, where it remains today. And despite his nephew’s accusation of flim-flam, Josiah Stowell remained friends with the young, failed scryer. In an 1834 letter written on behalf of the ailing Stowell to Smith, who was then living in Nauvoo, Illinois, the old farmer promised to “come up to Zion the next season.” Both men were dead within a year after the letter was written. But we’ll get to that. And we’ll also get to Zion.

It wasn’t too long after the Stowell job that Smith announced something truly extraordinary, his mighty unearthing. It was not pirate plunder. Nor the contents of a chieftain’s grave. Rather, as he would tell thousands of men and women, he stumbled onto something infinitely more marvelous. A stack of golden plates engraved with mysterious script, which he dug from the side of a hill called Cumorah. With this claim, he created a new identity on this account—the discovery of platters, scribbled with stories, that he told his followers he’d translated and written within the pages of the Book of Mormon.

These plates had not come from scrying, Joseph declared, but rather from a visiting angel named Moroni. Years later, and well into his launch of a modern world religion, he recalled an angel floating in the air who wore a robe of “exquisite whiteness.”

It was a whiteness beyond anything earthly I had ever seen; nor do I believe that any earthly thing could be made to appear so exceedingly white and brilliant. His hands were naked, and his arms also, a little above the wrist; so, also, were his feet naked, as were his legs, a little above the ankles. His head and neck were also bare. I could discover that he had no other clothing on but this robe, as it was open, so that I could see into his bosom.

After several more visits, the angel encouraged Joseph to go dig up the plates.

Though the words etched upon the plates were initially inscrutable, Joseph said that luckily he’d found magic tools along with the plates, an Urim and a Thummim, necessary for decoding what he declared was a type of reformed Egyptian writing. Using their power, Joseph went back to a process he knew so well, plunging his face into the opening of his hat and staring into the darkness toward his own seer stone perched in its crown. Conjuring the engraved contents from the darkness, Joseph translated the words, revealing the plate’s tales to his trusty scribes, Emma, Oliver Cowdery, and Martin Harris. The process was first carried out from Joseph’s and Emma’s home in Harmony, Pennsylvania, and later, he and Cowdery went to Fayette, New York, to finish the work.

The platters, Joseph claimed, contained a history of America written by a man named Mormon and later edited by his son Moroni. They told of a lost tribe of Israel, a family who traveled west in 600 BCE, and the descendants who spread throughout the Americas. For over a thousand years, two lineages, one descended from a man named Laman and the other from his brother Nephi, fought battles against each other as they struggled with various degrees of success to follow the word of God. Eventually, the Lamanites, those descended from Laman, killed off the Nephites, those descended from Nephi, but, over the centuries, the Lamanites forgot their origins. Joseph Smith believed the Lamanites were in fact American Indigenous people, whom God had punished and left with dark skin for their transgressions.

This racist notion was not unique to Smith, as many white Christians regarded skin color as “the curse of Ham”—this in reference to the passage in Genesis in which Noah punishes a son by that name. Ham had come across his father lying naked in a drunken stupor, and for this act, which Noah felt was one of disrespect, he hexed both his son and the entire land of Canaan. Although there is no mention of Noah’s actual spell, it was somehow decided in the Middle Ages that the curse of Ham conferred dark skin. This became a justification for enslaving those who were not white. By using the curse of Ham as a device, people in servitude were seen as deserving of their fates. Prominently used in nineteenth-century America to justify slavery, the idea was embraced by the Mormons, who carried it westward and into their Indian missions. The church maintained that the jinx could be reversed through an act of Mormon conversion, fostering a long history of pressure on Indigenous peoples to embrace Mormon culture and leave their own behind. The curse of Ham also influenced church policy prohibiting African American men from joining the Mormon priesthood until 1978.

In 1830, the Book of Mormon was published and it became an essential element, even the key, to building Joseph Smith’s church. He had something the various sects of upstate New York did not—his very own bible. Joseph was offering an American gospel, an actual sacred story that had been unfolding on American soil. The book told of Jesus visiting the Americas after his resurrection. It offered a history of the chosen people, who were Americans, and it explained the presence of Native peoples and where they’d come from. With the Book of Mormon, America was a new and improved Jerusalem. To believers, it was a restored gospel, a contemporary and comprehensive explanation of Christian theology. It attracted followers who saw in his Book of Mormon new information giving fuller meaning to the Old and New Testaments. Like fitting together pieces of a puzzle, when these texts were interpreted together, an up-to-date vision of God became available to Joseph’s flock. Joseph’s sacred book gave proof that God continued to engage in an ongoing dialogue with humanity.

Many were attracted to Joseph Smith and his bible written from golden plates, but not everyone. Many called it forged or a bad biblical rip-off. Among them was Mark Twain, who combined all of these accusations in his own assessment, written years after its publication, calling the Book of Mormon a “pretentious affair, and yet so ‘slow,’ so sleepy; such an insipid mess of inspiration. It is chloroform in print. If Joseph Smith composed this book, the act was a miracle—keeping awake while he did it was, at any rate.” He continued, writing that “the book seems to be merely a prosy detail of imaginary history; the Old Testament for the model; followed by a tedious plagiarism of the New Testament. The author labored to give his words and phrases the quaint, old-fashioned sound and structure of our King James translation of the scripture.” The text, Twain added, is so jammed with biblical-sounding expressions such as “and it came to pass,” that, had this particular idiom been discarded in the final product, “his Bible would have been only a pamphlet.”

Although the book had detractors, within a few years after its publication, Smith had hundreds of devotees, earning him the reputation of a real live, flesh-and-blood prophet of God. This man, seemingly capable of revealing God’s truth in real time, was like a modern-day John the Baptist. It wasn’t just the Book of Mormon. Throughout his life, Joseph Smith received messages from God that influenced the direction of his religion and his people. Throughout his life, prophecy and revelation came fast and furious; after his death, “God’s truths” spread out across the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau.

But while Joseph was able to share his book, the holy plates were another story. Moroni, Joseph claimed, wanted them back. A handful of witnesses did testify to their existence; some saw them in visions and others claimed to have glimpsed or “hefted” them while they lay draped in cloth. But it doesn’t really matter. The truth of their existence is not the point. What really matters are the people who joined the Mormon Church and their descendants, those who brought Joseph Smith’s ideas into their unique identity. Publication of the Book of Mormon earned Smith the authority to launch his ideologies along a far-reaching trajectory. His book was but one text in a career that produced voluminous doctrines, sundry revelations, and complicated theologies. What Joseph Smith left behind has superseded his thirty-nine years. Plates or no plates, interpretations of his prophecies are as important today as they were when he walked the earth.