Читать книгу American Zion - Betsy Gaines Quammen - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

A map of the American West is a Rorschach test—people see what they want to see as reflections of who they are. There are those who see land solely for human utility. And those who see a realm for wild creatures. Some see the West as a place of colonialization and genocide, where the indomitable mettle of Indigenous peoples nevertheless endures. Some see a land of plunder, evidenced by slag heaps, old mining pits, and the abandoned equipment of long-ago endeavors. There are empty corners where a look in any direction reveals no obvious human marks, though the marks exist. This is a land heavily trod. Dying towns punctuate the old highways, their Main Streets marred by boarded-up windows, their schools emptied by dwindling enrollments. These towns are just miles from robust cities, ballooning with the influx of new residents and tech businesses. The West is a place of a thousand destinations—on rivers, on mountains, on prairies, and on rocks. It’s where cars speed down lonely roads, flanked by grazing horses and cattle, fence lines and range, billboards and baled hay. It is a place of differing points of view, a place of intersections and of loggerheads. People see their own ink blots here, spread across a land colored by custom, ambition, opportunity, and cows—sacred and otherwise.

The Intermountain West, a region of such differing interpretations, is geographically delimited by the Rocky Mountains to the east, the Cascade and Sierra Nevada Ranges to the west, and encompasses the Columbia Plateau, the westward drainages of the Northern and Southern Rockies, the Great Basin and the Mojave Desert. On the map, it is a large jumble of boundaries and ownerships with checkerboard designations and varying jurisdictions, sometimes running across state lines. A cartographic color code and a series of demarcations make one thing crystal clear: most of the Intermountain West is federal public land. Which means that all Americans, as citizens and taxpayers, are proprietors of some of the most incredible real estate on this planet. The best part of the West is that we share it—in all its fraught majesty. And this affords opportunity for further insights into how this land is variously construed. Somewhere between 280 and 560 generations of Indigenous people have been young and grown old here on the western landscape. Today, 327 million Americans participate in its proprietorship.

Public lands are precious and beloved places to westerners and non-westerners alike. They are finite and fragile, and have very real thresholds of tolerance to ruination. And there’s the rub. Some people are asking too much of these lands and, in doing so, are declaring war both on nature and on the millions of people who also share public lands. This is nothing new. The West has always been a place of competing cultures and priorities that began with cultural and resource conflicts among Indigenous nations. As Europeans arrived and homesteaded, their claims to these lands were devastating for Native peoples. Not long after settlement slowed and the “western frontier” was closed, a battle between preservationists, timber barons, and ranchers spurred the creation of national parks and monuments and set the match to land wars that still burn today. Mining companies, four-wheel-drive enthusiasts, and those in livestock production have wrestled for control over lands that wildlife need and conservationists fight to protect. It falls to the American public to decide how these lands should be understood and managed. Should these lands be a place for recreation or for industry? For carbon sequestration or for resource extraction? For short-term gain or long-term viability? For everyone or a few individuals? To repeat the obvious: these lands belong to all Americans, yet their use is being determined by a limited number of politicians and rogue players.

I want to pause here and confess that the idea that these lands belong to all Americans is a laden one. Public lands are originally and rightfully Native lands. It seems like there is a way to reach some reconciliation, acknowledge the violations of the past, and engage collaboratively on issues of land use, wildlife, water, and sacred sites, among others. Such a partnership happened with the 2016 establishment of Bears Ears, a national monument in Utah, where five tribal nations worked with conservationists and federal land managers to protect cultural and ecological attributes. Under the current administration, this conservation effort, along with so many others, has been undermined by those who aren’t concerned with Native rights or public interest. In the meantime, the priorities of Native peoples and a majority of other Americans have taken a backseat to the pursuits of fossil fuel interests, political agendas, and rural old-boy networks.

Within these networks and agendas, an old archetype inextricably linked to these lands has emerged, undeservedly, as a sort of ideological hood ornament in the fight over public lands. This archetype, embodied by certain western men and women, carries powerful cachet, over a hundred years in the making. His avatars might don bolo ties, boots, and big belt buckles. He, or she, might ride horses or drive ATVs and pickup trucks. An iconic figure lies behind those choices and affectations, looming large in the American imagination and in the career aspirations of children the world over. He is the cowboy, and he exerts an inordinate amount of power in public land management. But take a second glance and the cowboy isn’t what he seems to be.

The cowboy made his way westward several decades after Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and their Corps of Discovery returned from their expedition to the Pacific coast and back. Others followed in their footsteps, looking for economic opportunities and a place to call home. Some of these pilgrims pursued farming, others chased gold, and some began cattleranching. That’s when the cowboy inserted himself into the western landscape, joining fellow settlers, railroad-track laborers, and the armies that protected them in a united campaign to drive Native peoples from their homeland.

The white cowboy hero may be a dwindled icon in our own age—his embodiments are fewer and further between, though a wonderful renaissance of the African American cowboy is resurfacing with the Compton Cowboys in California—but his mythic resonance remains, so potently was it charged by the romantic imaginings that arose around him when he first burst onto the scene. Newspapers, novels, films, and cigarette commercials have glorified him as brave, resourceful, and the very epitome of a hero. But the very term, cowboy, needs some critical unpacking. The real cowboy, the original, was a hired hand, not a boss rancher. His proud label became a useful catchall, because so many livestock producers relate to cowboys and look like cowboys and represent themselves as cowboys. Folks living outside the West might not even know the difference, but, given their meager wages, cowboys both know and feel the difference between themselves and the head honcho. Still, be it beefindustry executive or a proletarian cowpoke, imagine this figure seated on his saddle, atop his horse, under the wide brim of his hat. An imagined master of his home on the range, moving herds of lowing bovines to graze acre after lonely acre, sharing western grass, sometimes begrudgingly, with roaming buffalo, deer, and antelope. You get the picture—you’ve seen or heard about it a million times.

The cowboy made his first big public impression in 1902, swaggering into American popular culture by way of Owen Wister’s novel The Virginian. Wister’s book, adapted from several short stories he had earlier published in magazines, traced the life of a self-made cowboy, an amalgamated man who combined eastern gentility with western gumption and grit. This hero is simply known as the Virginian; he’s a man without a name, and his story is told by a pal, Tenderfoot. The Virginian is handsome, tall, and the very epitome of decency. Plus he’s sexy. “He climbed down with the undulations of a tiger, smooth and easy, as if his muscles flowed beneath his skin,” according to Tenderfoot, deeply impressed by their first meeting.

The Virginian begins as a cow puncher, moves on to be foreman, and later becomes part owner of a Wyoming ranch—the ultimate cowboy dream. Over the past hundred years, Wister’s work has been adapted into six movies and a TV series, and served as a template for countless other western novels, movies, TV series, comic books, video games, and marketing campaigns around the world. This original mythic cowboy, the Virginian, also set an example of individualistic entitlement. Toward the end of the novel, he proclaims: “I’m going my own course. Can’t you see what it must be for a man?” His entitlement becomes his destiny.

Apart from books and imaginations, the cowboy figure carries real baggage—more than enough for a pair of saddlebags. In the nineteenth century, real cowboys and their trail foremen arrived in the Intermountain West with millions of cows, moving them through the rugged landscape, facing brutal winters and deep snows as well as blazing summers, high rivers, drought, and quicksand. These bovine residents helped the cowboys co-opt grasslands for the rancher bosses, working through both legal and illicit channels to acquire more ground and access to federal grass left unclaimed by homesteaders. When this era of the unregulated rangeland free-for-all came to an end, Native peoples had been displaced and killed. Bison were nearly extinct, in part due to an effort to starve the Indigenous population, and western lands were left trashed.

As the twentieth century began, the US government—and the cowboys themselves—realized that things had to change. Legislation to regulate grazing and to protect the land became a priority. Massive western cattle drives, in which millions of cows were moved from arid to green, or from pasture to market, came to an end. Herd limits and designated allotments for livestock producers on the public domain were developed, with a grazing management system that remains in place today. Over the years, regulations have increased in the West, in places once left unchecked, causing some public land cowboys to chafe with each new rule. Many permittees rely on public lands as range, because their own private ranch property is inadequate to support viable herds. You need thousands of acres of land to raise cattle, because the West can be dry and stingy. Luckily for those operators who depend on it, renting federal land is cheap. Livestock producers pay on average thirteen times less to graze on public range than they would if they were leasing private lands. The cowboy of yesteryear was grazing open, unregulated public domain on stolen Native lands. Today he grazes that same land on public subsidies.

Presently, the government manages 5,863 active grazing leases on Forest Service lands (which are held within the Department of Agriculture) and the Department of the Interior manages another 18,000 permits granting grazing privileges. While many of these modern-day leaseholders have perfectly workable relationships with the government, some do not. In fact, certain livestock operators who run cows on public lands have come to deeply, and even violently, resent federal controls. The cowboy once grazed his animals with no oversight, and for some, that open-range era represents the epitome of freedom and independence. But the lack of regulation was neither sustainable nor benign. The early liberties afforded this low-maintenance livestock production have come into conflict with shifting American values. The public’s interest in western lands has evolved, from the romantic distortions of Wild West movies and television shows to today’s better understanding of the damage unregulated livestock grazing wreaks on the landscape, from devastating erosion to noxious weeds to wildlife extirpation. Over the years, elected officials, encouraged by a voting public keen on conservation, have drafted and enacted measures to protect shrinking western resources by regulating livestock. And with the enforcement of these laws, as well as market forces, costly droughts, and alternatives to wool and leather, some ranchers on the public range, where seldom was heard a discouraging word, got—well, discouraged. The cowboy, once kingly, got stripped of a near-royal prerogative—the unimpeded reign over American western lands.

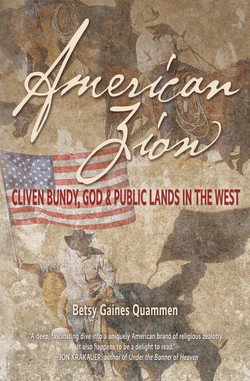

And this brings us to our story. There’s a rancher in Nevada who is determined to preserve his cowboy image and the mythology, the prerogatives, that come with it. For over twenty years, Cliven Bundy has let his cows graze illegally on a chunk of Nevada public land (in the Mojave Desert’s fragile habitat) without permission from the United States government or the public. Bundy has paid no grazing fees since 1993 when he stopped in protest, later ignoring the 1998 cancellation of his lease agreement. Nonetheless, Cliven feels justified. He says that he knows his rights better than anyone else, and has no interest in other notions about land management. Nor has he time for Native historical claims, wildlife habitat, federal laws, or the rights of all other Americans who share ownership of this common ground. Like the Virginian, Cliven Bundy has decided to go his own way.

Over a course of decades, this man, in the process of flouting the law, has become a hero to some in the West. He has engaged thousands of followers, from other ranchers to anti-government militia to officials in the Trump administration, in a fight against the principles governing public lands. He has gathered support to abolish public land ownership altogether. He makes frequent reference to himself and his followers as “we the people,” as though only Bundy and his followers did “ordain and establish” the US Constitution. In representing himself as the proxy spokesperson for all Americans, he refuses to grasp that his positions defy the interests and the will of his fellow Americans. Americans who know and love public lands, love them—as wildernesses, parks, forests, prairies, monuments—not as rangelands. But Bundy believes that he has the corner on land-rights issues, and that his point of view is better informed, more substantial, and more warranted than the viewpoints of the rest of us. Why? In part, it’s because he fancies himself a cowboy whose home is on the range. But there’s so much more to his campaign. Cliven Bundy has gathered other potent myths to substantiate his fight—ones that orbit his religion. He is a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and has employed a unique syncretism that blends the legend of the cowboy with early Mormon beliefs. Bundy has convinced himself and others that God wants him to go to war over our public lands.

The West is full of stories. In fact, there are a million more tales than there are cowboys. But this one is, among other things, a cowboy story. It is not a celebration of the cowboy. Nor is it a condemnation of all those who call themselves cowboys. It’s the story of the emergence of rancher Cliven Bundy, his family, and his followers, onto the western stage. It’s a story of magic, history, prophecy, AR-15s, gods, and cultural convictions standing at odds to one another. It is also my plea to the American public to come to the aid of lands now under siege on multiple and unimaginable fronts. This story has a long prelude, beginning nearly two hundred years ago on the other side of this country when a new religion arose, and that religion was then carried to Nevada and Utah by the people who practiced it. Those pilgrims, when they came west, not only brought their new faith, but also carried animosities and certitudes which they pounded into the very lands where Cliven Bundy runs his cows today. These characters of the prelude, these Mormon pioneers, are Bundy’s people. They are his ancestors. And once they settled in the West, they were determined never to leave—most especially not at the insistence of the United States government. To the Bundy family, the land where their cattle graze, these publicly held lands, is their property, their homeland, and the family has vowed to defend it or die trying.