Читать книгу The Tree that Sat Down - Vita Sackville-West, Beverley Nichols, Beverley Nichols - Страница 7

Chapter Two THE STRANGEST SHOP IN THE WORLD

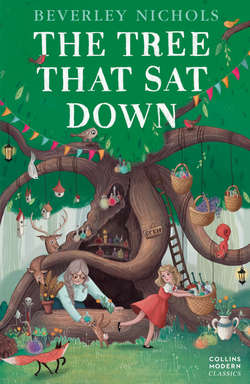

ОглавлениеTHE SHOP UNDER the Willow Tree might just as well have been called The Shop In the Willow Tree, because it would have been impossible to say where the shop began and where the Tree ended. It was a very old tree indeed, so old that the trunk had split open, forming a sort of cave, in which there was always a candle burning at night. When it was cold, Mrs Judy slept in the cave; otherwise she slept in a hammock high up in the branches. She used to swing backwards and forwards in the wind, and if you had looked up through the branches, on a wild night when the clouds were scurrying across the moon, you would have thought that she was some strange bird that was resting there.

The main business of the shop was conducted in what Mrs Judy called the ‘Extension’. This was really an immense branch which had sagged away from the trunk, through sheer age, and had come to rest on the ground, forming a sort of arch. The branch was not dead; it was just old, and it felt that it had earned the right to sit down. And so the arch was a living arch, pale green in spring, gold in autumn, bare in winter – but always strong and warm. Underneath the arch Mrs Judy had dragged an old log, and it was this log which served as a counter.

Apart from the Tree itself and the ‘Extension’ there was another department which Mrs Judy called the ‘Bargain Basement’. This had originally been only a dip in the ground, but Mrs Judy had hollowed it out till it was about four feet deep, and cut some steps down to it, and scooped away the earth from the rocks, which were large and flat, and made excellent shelves. On these shelves were displayed an extraordinary variety of objects, ranging from coconuts for the tits to toy mice for the Manx children.

It was really a wonderful shop, and there were hundreds of things that would have interested you, stored away in the hollows of the trunk or hanging from the branches. But we have not time to look at any more of them just now, because Judy is coming home and we must get on with our story.

*

When Judy had told her grandmother about Sam, Mrs Judy looked very grave.

‘I was afraid this would happen one day,’ she said. ‘We are faced with Competition.’

‘What is “competition”, Grannie?’

‘Some people call it “progress”, others call it “the survival of the fittest”; but whatever name they use, it is always cruel.’

‘Never mind. We shall pull through somehow.’

‘It will not be easy. I am very old.’

‘But the animals all love us.’

‘Yes – but animals are simple creatures. They are not as simple as humans, of course, who spend their whole lives being cheated and deceived. If a man wants to make up his mind about something, he has to read a book about it, and even then the book will often tell him lies. But an animal can sum up a man’s character in a single sniff; an animal can tell whether a man is a friend or an enemy simply by listening to his footfall on the grass. And that is really the most important thing in life, to know who are our friends and who are our enemies.’

‘In that case, surely the animals will know that Sam and his grandfather are their enemies?’

Mrs Judy sighed. ‘I wonder. Those two sound as if they are very cunning. And remember – they are going to give the animals something new, something from the outside world, of which they have no experience. For instance, you told me that they are going to use advertisements. Now human beings know that advertisements are often just another name for lies. Some advertisements are true, of course, some are half-true, but many are plain unvarnished lies. The animals will not know this, because the advertisements will be written up in print, and the only print the animals have ever seen has been in our own shop, and we have never printed anything that has not been true. So the animals will think that print and truth are the same, and if we tell them that print can tell a lie, they will only think that we are jealous.’

‘Oh, why did they ever come to the wood?’ cried Judy. ‘We were so happy here.’

Mrs Judy stroked her hair. ‘We shall be happy again,’ said Mrs Judy. ‘But we shall have to think. We shall have to get some new ideas ourselves – better ideas than any that Sam can think of.’

‘But where shall we get them?’

‘From the Tree of course.’ Mrs Judy spoke quite sharply. She had lived so long under the old willow, climbing its great branches by day, sleeping snugly among its giant roots at night, that she had come to regard the Tree as almost human. More than human, in fact, for she felt that the Tree had some magical power to protect them both, that no harm could come to them as long as they dwelt in its shadow.

‘I don’t see how the Tree can give us any ideas,’ sighed Judy.

‘Ssh! Don’t say such things!’ Mrs Judy looked anxiously upwards; she was afraid that the Tree might hear, and be offended. And sure enough, at that moment there came a cold gust of wind that set the branches swaying and set up a thousand little whispers among the leaves, as though the Tree were murmuring to itself.

But what was it saying? What was the message it was trying to give them?

‘Time will tell,’ she thought. And with that, she had to be content.