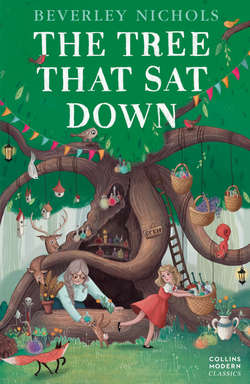

Читать книгу The Tree that Sat Down - Vita Sackville-West, Beverley Nichols, Beverley Nichols - Страница 9

Chapter Four THE STRUGGLE BEGINS

Оглавление‘YES,’ AGREED MRS JUDY, on the following morning, when she had heard the whole story, ‘something must certainly be done.’

It was nearly twelve o’clock, and not a single animal had come near The Shop Under the Willow Tree. Not that they were not still very fond of Mrs Judy, but Sam had been so clever with his advertisements and his smart talk that they all thought that they could buy much better things at The Shop in the Ford.

Besides, Mrs Rabbit had been so proud of her beautiful locket that she had been scampering through the wood ever since breakfast, showing it to all the other animals, who thought it was a wonderful bargain. And so Judy’s kind action had only served to injure Judy herself. Which is often the way of kind actions, though that should not prevent us from performing as many of them as we can.

‘We shall be ruined,’ sighed Mrs Judy.

Judy smiled bravely. ‘No, we shall think of something. Perhaps Sam is right when he says we are not modern.’

Mrs Judy snorted. ‘Modern! Of course we’re not modern. What’s the point of being modern? What’s better in the world today than it was yesterday?’

Judy could think of no answer.

‘Well,’ said Judy, changing the subject, ‘what we have to do is to persuade the animals to buy more.’

‘Buy more what?’

‘More anything. And I really think we ought to go all round the shop now, at this very minute, and see if there isn’t anything we can improve.’

*

‘Let’s begin with the Nest Department,’ suggested Judy.

The Nest Department lay under the shelter of a very old and twisted branch of the Tree that had fallen to the ground so many years ago that most of the bark was crumbling to pieces. The nests were arranged in neat piles, and each pile was labelled. Like this:

Nests. Top bough

Nests. Middle and lower boughs

Nests. Hedge

Nests. Eaves

Nests. Cuckoo-proof and Cat-burglar-proof

Nests. Ground floor

There was also a little catalogue hanging on a twig, with a label on the cover, bearing the words, ‘Nests, sites for …’

Judy had taken a great deal of trouble over these nests, and at first they had been a great success, because she had been able to supply the demand of almost any bird in the wood. Judy had only to go to the pile, find the right nest, and then turn to the catalogue to see what branches were ‘to let’. The index of the catalogue began with Acacias (white) and ended with Willows (weeping), and in a few moments she had found what was wanted.

But now, Judy was bound to admit, the nests did look rather dilapidated. She had been so busy in other departments that she had not had time to attend to them, and many of them were falling to pieces.

‘No self-respecting bird would buy any of these,’ said Mrs Judy. ‘Lots of them have holes in the floor so that the eggs would fall out.’

‘Oh dear! So they have!’ Judy picked one of them and turned it over in her hands. Then she had an idea. ‘Supposing I made some beautiful new ones, with a partition down the middle? Then we could put in a lovely advertisement: “Ultra-Modern Two-roomed Nests. Exclusive.”’

‘With central heating, I suppose,’ sniffed Mrs Judy sarcastically.

‘I don’t think we could quite run to that,’ replied Judy. ‘But I do think the two-roomed idea is a good one.’

Mrs Judy shook her head. ‘It’s downright pampering.’

‘But Grannie, we must move with the times.’

‘Very well. Have it your own way.’

*

Their next visit was to the Novelty Department, which was really Judy’s favourite. As they walked through it, she became so interested, and had so many new ideas, that for a time she forgot her troubles. She even forgot the wickedness of Sam.

There were all sorts of shelves and niches and pigeonholes, containing the strangest and most exciting objects, all at the most reasonable prices. For instance, if you had been looking over Judy’s shoulder, on that sunny morning, the first thing you would have noticed would have been a tiny hole labelled:

PORCUPINES – NEW QUILLS

And if you had pushed your finger into the hole, you would have pulled it out again very quickly, for it was stuffed full of the sharpest quills you can imagine. Mrs Porcupine used to say that she only wished she could meet a human when she was wearing them; she’d teach him a lesson!

Judy paused in front of a row of pale blue bottles labelled:

GARGLE FOR NIGHTINGALES

‘We haven’t sold much of this lately,’ she said, ‘although the nightingales have been giving concerts every evening. Do you think it’s too expensive?’

‘Can’t make it a penny cheaper,’ retorted Mrs Judy. ‘It takes ages to make. First I have to get a water lily and pour in an acornful of apple juice. Then I have to add thirty drops of liquid honey and the juice of nine nasturtium seeds. Then I have to collect three dew-drops off the petals of a yellow rose and drop them in, one by one, stirring it all the time with a corn-stalk. That takes time, I can tell you, apart from all the poetry I have to say.’

In a sing-song voice Mrs Judy repeated the following poem:

Here’s honey for the honey in your throat

To make it sweeter still.

Here’s dew as pure as every golden note,

Here’s magic – drink your fill.

Then to the starlight let your music float

But first – please pay the bill!

‘It’s very pretty indeed,’ said Judy. ‘And I don’t think the gargle is at all too expensive, not with the poem. But perhaps there are some things we might make cheaper. What about this Blackbeetle Polish?’

‘Yes,’ agreed Mrs Judy. ‘We can charge less for that. It’s only coal dust and olive oil.’

‘And then there’s the Ladybird Lacquer.’

‘We can’t charge less for that because it takes a thousand poppy petals to make a single drop.’

‘Couldn’t we make it not quite so strong?’

‘If we did, it would come out pink, and there’d be a scandal. Imagine a pink ladybird!’

‘It might be rather pretty,’ suggested Judy.

‘It might, but the ladybirds wouldn’t think so. They’re such snobs; they’d say it was “unladybirdlike”. And when they say anything’s “unladybirdlike”, that’s an end of it.’

‘What about the Food Department?’ asked Judy.

‘We can’t cut prices much more than we have done already.’

‘Still, we might think of some new ideas. For instance, Mrs Moth came in yesterday, but she flew away without buying anything.’

‘She was always a fussy one,’ sniffed her grannie.

Judy reached for a box on which were painted the words:

MENUS FOR MOTHS

She opened the lid and drew out a number of pieces of cloth, cut into neat strips, and bearing attractive labels. For instance, there was a square of old grey silk labelled ‘Delicious!’ And there was a piece of blue serge labelled ‘Very Nutritious’. And there were several pieces of hearthrug labelled, ‘Try them … they’re Tasty!’

‘Mrs Moth said they none of them had any vitamins in them,’ sighed Judy.

‘Stuff and nonsense! What does she want with vitamins? Her mother brought up a whole family on half an old sock, and she never complained about vitamins.’

‘All the same, we have got to give the animals what they want. I think I’ll cut up my red silk handkerchief.’

‘It would be a shame. Besides, they might not like it.’

‘Oh yes they would. Mrs Moth saw it yesterday and said it made her feel quite hungry.’

‘Very well. Only mind you charge a proper price for it. And think of some extra special label.’

‘I shall put “Melts in the Mouth”,’ said Judy.

They went all round the department, making notes. Judy decided to do some more crystallized acorns, which were always so popular with the squirrels, and to get some more coconuts for the tits, and paint the outsides of the shells pink and blue.

‘And we’re running short of ants’ eggs,’ she said. ‘I must go out and buy a fresh stock.’

Her grannie stamped her stick on the ground. ‘Ants’ eggs!’ she exclaimed. ‘I knew there was something I had forgotten to tell you! You remember the ants under the damson tree?’

‘Of course. I’ve bought eggs from them for years.’

‘A nicer lot of ants I never knew. Hard working, sober, and most patriotic – quite devoted to their Queen. It is too terrible.’

‘But what has happened?’

‘Wait till I tell you. Some of them came round this morning – oh, in a dreadful state. Battered and bruised and carrying on as though there’d been an earthquake. And as far as they were concerned there had been an earthquake; that wicked Sam went round with a spade last night and dug them all up and carried away all their eggs.’

Judy could hardly believe her ears. ‘You mean – he stole them?’

‘Certainly he stole them. Not only that, he chopped half the nests to pieces. And when the ants said they’d have the law on him he only laughed and said that if they breathed a word to anybody he’d come and pour boiling water on them.’

‘Oh dear!’ cried Judy, almost in tears. ‘This can’t go on. We must do something. After all, there is a law in the wood.’

‘Yes, but it’s a law for animals, not for humans.’

‘It isn’t only the animals who will be ruined, it’s us. Look at the ants’ eggs, for instance. They used to be one of the most profitable things we sold. The goldfish were the richest fish in the stream and they never minded what they paid. And now Sam will be able to sell them for practically nothing. Is there nobody who can help us?’

‘If the worst comes to the worst,’ said Mrs Judy, ‘there is always the Tree.’

‘But what can the Tree do for us? It can’t give us anything.’

‘Hush, Judy! It can give us shelter.’

‘But that isn’t something that we can eat.’

Mrs Judy paid no heed; for a moment she seemed to have forgotten her grand-daughter. She was gazing up into the branches of the Tree, lost in a dream. ‘And it can give us Beauty,’ she said.

Judy felt like retorting that you couldn’t eat Beauty either, but there was something in the tone of her grannie’s voice that made her pause – something strange and solemn.

She said nothing, but followed her grannie’s eyes up into the topmost branches of the Tree. And as she gazed, there came a fresh, sweet breeze, that sighed through the boughs and set all the leaves to dance, twisting and turning, green and silver, and where the sunlight caught them, pure gold. They all seemed to be laughing and happy, as well they might; for what could be lovelier than the life of a leaf, high against the sky, with the wind as your brother and the sun as your friend, and the whisper of your companions all about you?

‘Beauty,’ whispered Grannie once again.

And the wind seemed to catch the word, and breathe it to the Tree, and the Tree sang it back in a thousand gentle voices … Beauty, Beauty, Beauty.

And suddenly Judy sat up and opened her eyes very wide and cried, ‘Grannie, I’ve got it.’

*

Mrs Judy blinked.

‘Got what, my child?’

‘I’ve got an idea. We’ll open a Beauty Parlour!’

‘Whatever put such an idea into your head?’

‘The Tree.’

‘I can’t believe the Tree said anything so foolish. The animals are quite beautiful enough already.’

‘Then why do we sell lacquer for ladybirds?’ asked Judy. ‘And if it comes to that, why do we sell Blackbeetle Polish?’

Mrs Judy frowned, for she was a very old lady, and she did not like to be contradicted. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘that’s a matter of health.’

‘But Grannie, darling, that makes it better still. Beauty and Health. What could be better?’

‘We might open a Surgery,’ agreed Mrs Judy, grudgingly.

‘Why not both?’

‘It’ll mean a lot of work.’

‘But I could do all the Beauty Parlour. And I could help you in the Surgery, too.’

‘You couldn’t help with the Magic,’ said Mrs Judy. ‘That would all fall on me.’ She shook her head backwards and forwards. But Judy could see that she did not really mean it, for there was quite a bright sparkle in her eyes.

‘I shall have to read up a lot of old books,’ went on Mrs Judy. ‘And I shall have to polish my magic crystal and mend my magic wand.’

‘But Grannie, I didn’t even know you had a magic wand.’

‘Well, it’s rather old and cracked so I expect most of the magic has run out of it now,’ said Mrs Judy. ‘Still, there’s no harm in trying. Deary me! We shall be busy for the next few days!’

Judy clapped her hands. ‘I’m so excited. Let’s begin now, this very minute. What is the first thing you would like me to do?’

Mrs Judy thought hard for a moment. ‘Well, my dear, I think that the first thing you should do is to say “Thank you” to the Tree for giving you such a good idea.’

‘Thank you,’ said Judy, rather shortly.

‘You must say it much more nicely than that,’ corrected Mrs Judy. ‘Say … “Thank you, Tree, for all that you have done for us, for your shelter and for your shade and for your wisdom.”’

So Judy said these words. And once again a little breeze sighed through the topmost branches, so that you would have sworn that the Tree had heard, and had bowed its head.

‘And now,’ cried Mrs Judy … ‘and now … to work!’