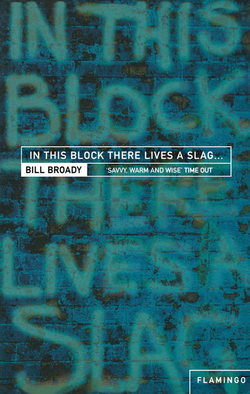

Читать книгу In This Block There Lives a Slag…: And Other Yorkshire Fables - Bill Broady - Страница 7

In This Block There Lives A Slag…

ОглавлениеIn those days I could really sleep. I’d never have woken up at all if it hadn’t been for the clocks. It was bad sleep though – I never remembered my dreams but I knew that they must have been nightmares. I had these three clocks set at thirty second intervals: first the bedside radio alarm that I’d tuned to a frequency of ghostly static, then, on the floor, the second, hooting like a robot owl, and finally, on the window ledge behind the curtain, the biggest – a great copper thing bearing a face with long-lashed eyes and a lipsticked mouth that smiled while, with twin hammers, it tried to beat its own brains out. I had to get over to it before, in detonating, it destroyed the world.

That morning, as usual, I wrenched the curtain off the end of the rail and down on top of me. For weeks I’d been chanting ‘baulk screws, baulk screws’ under my breath like a mantra but I never remembered to buy them. I even wrote the words on my hand but either they rubbed off or I forgot to look. The sunlight was dazzling me, reflecting off a fourth-floor window of the adjacent block: it looked as if The Yellow Man was hiding out in a Bradford Council flat. I was out of bread and milk so I breakfasted on a leftover half samosa and the dregs of six cans of Skol, crushing them as if to squeeze out any last drops. I knew that my depression wouldn’t lift until lunchtime, about halfway through the third pint.

To wake up fully, I threw myself down the stairs, Starsky and Hutch-style. I never used the lift: it smelled of burning and felt to be going not up or down but sideways or even somehow inwards, like a time machine. Outside, I could feel the glass from broken milk bottles even through my Air-Wear soles: although it had been there a year no one had cleared it up. The lad who cut the verges wouldn’t do it: ‘It’s not my job,’ he’d said, ‘I’m the gardener.’ So I’d kicked it onto his grass but he’d merely mowed around it. Still, it was useful for finding my way back when I was out of it: I knew to turn left when I heard the glass crunch under my feet, then to kick each stair riser until I recognized my floor by the sound of some liquid steadily dripping from somewhere. When I first moved in I was always getting lost, finding myself fumbling with a key that suddenly didn’t fit a mysteriously repainted door.

My lock-up didn’t lock – but it would only open if you banged the jammed shutter top left while simultaneously booting it bottom right, then, while it was still vibrating, pulled and twisted its handle so sharply as to nearly dislocate your wrist. It was thief-proof, but then who on earth would have wanted to nick my van?

This morning only the dogs were about, sweeping back and forth in splitting and recombining packs: they weren’t like ordinary mongrels – it was as if a transplant surgeon had crazily jumbled up a dozen pedigree breeds. Now as they mobbed together it seemed that the legs and heads were frenziedly trying to match themselves up with the right bodies and tails. The Health Department had been baffled by the speed at which our local typhoid epidemic was spreading until they’d established that it was through all those dirty nappies the young mums kept throwing out of the blocks’ windows: The dogs would lick them, then lick their owners’ faces.

I set out for a roofing job in Bradford 13. The van jerked and roared and pumped out black smoke. Even through the city centre they gave me ten yards clearance, front and back. I hated driving up Thornton Road. First its mills had closed, then its light industry, then the butchers and the bakers, until all that was left was dereliction and decay. I’d liked that fine but then bright new frontages had appeared with bewilderingly kaleidoscopic window displays: Waggy’s Fancy Dress Hire, Ken’s Kendo Accessories, The Moonchild Magick Shop, Pets and Patios…I was glad I’d had the sense to drink away my own redundancy money.

The woman who’d rung greeted me as if I was a Boy Scout on a Bob-a-Job. At five feet nothing she still managed to give the impression that she was looking down on me. Her pipe cleaner legs bent under the weight of her sack-like body and the skin of her face, above three rolls of chin-fat, was stretched taut, as if she was suffocating inside a plastic bag. She was wearing tight flowered shorts with a cake fringe border and a black Lycra sports bra that was gradually disappearing between folds of flesh. She pointed up at the roof and clicked her fingers, then went into the house and made a cup of coffee, without offering me one. I told myself that she must have had a lot of pain in her life – although probably it had been nothing like enough. I could hear her sniggering when I couldn’t get my ladders off the van rack. My usual granny knots had somehow mutated into a complex network of weird loops, hitches and twists. As I unpicked one, another three seemed to form: finally I took my Stanley knife and just slashed the ropes to pieces.

Most of the slates were missing on the roof’s west-facing side; even on a still day, gusts of wind kept exploding out of the two hundred square-miles of nothing much between here and Lancashire, sneakily trying to pitch me off. I started to clean the dead leaves out of the guttering. The woman sunbathed below: a thick book was propped open in front of her but she never turned its pages. Her tinny radio was tuned to Classic FM but I knew that she didn’t really like the music, just had it on to impress. To ‘The Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy’ she extricated her top and rolled over on to her front. I resisted the temptation to bombard her with the three slimy tennis balls I’d just uncovered. You came across some strange things in gutters: I once found a gold octagonal ladies’ watch – maybe it had been dropped by a jackdaw or fallen from the wrist of a passing angel? Suspicious of good fortune, I’d just left it there.

I went to the pub for lunch: four pints of Landlord, to wash down a Brontë Booster – an enormous egg, bacon and sausage fry-up. I tried to imagine Emily, Charlotte and Anne, born just across the road, getting their teeth into that. I watched a coachload of Jap tourists videoing each other being blown up and down Main Street; why were they so obsessed with the Brontës? Whenever I was driving over Haworth Moor I’d stop and twist the new signposts of Japanese characters to point in the opposite direction.

When I got back, my employer had turned over, her poor little tits slopping on to the grille of her rib cage: the sun seemed to be not tanning but bleaching her. The beer had restored my courage or my balance: from the roof I looked down like a God into the bowl-shaped valley that contained Bradford. My block and the others were sticking out of the heat-haze like the clutching fingers of a drowning man. I began to replace the corroded section at the back with the grey plastic guttering I’d nicked from the site of the hospital extension: I still felt guilty about this, so I wedged two blackbirds’ nests back in place. Sometimes they come back, year after year – what must it feel like, living in a nest?

A red Audi swung into the drive. Hubby was home: she didn’t even twitch as the car door slammed. I watched him enter the house: the top of his head, like a tonsured monk’s, looked familiar. He returned in matching floral shorts, carrying two cans of Heineken: he popped one and threw the other up to me. It was the manager of the Jobcentre where I signed on: I hoped that he hadn’t recognized me, silhouetted against the sky. He lay down alongside his wife in the shrinking patch of sunlight, his bare yellow feet next to her head.

When I finished he was waiting ready with another beer. He knew me all right. ‘Seventy for cash,’ I said. He smiled and counted three tens into my hand, paused, added two fives and then tucked his wallet back down the front of his shorts. There was nothing to be done. I glanced over at his wife, then at him, then dropped my hand and checked my flies but he wasn’t falling for it. His grin broadened and he shook his head slightly: he gave me credit for more taste.

After tearing my T-shirt into strips to tie the ladders back on, I let my van slide down into the city. At every red light I expected them to shoot off their rack and go through the windscreen of the car that crawled in front all the way, pulling out whenever I tried to pass, its driver’s billiard-ball head bobbing on a long, easily-severable neck.

As I was readying myself to lay into the shutters of my lock-up, coppers suddenly came at me from north, south and west. Two of them pinioned my arms while Mark the Community Policeman strolled up. He’d never decided whether he wanted to be a hard cop or a soft cop: one day he was all smiles, the next slamming anyone he saw up against the nearest wall – he even looked different, alternately fat and jolly or thin and mean. His hands dropped gently on to my shoulders, as if in a blessing: ‘So why did you do it, then?’ he asked me with a sigh.

‘Do what?’

The scrum broke up as they all skipped aside like chorus boys to point dramatically towards the windowless rear of my block.

| In this | block |

| there lives | a slag… |

| she’s hurt Him | and now |

| she has | to pay… |

The enormous gloss letters were bisected by the leaking downpipe, their ultrawhite glare almost bringing tears to my eyes.

‘I don’t know anything about that,’ I told Mark.

‘You’ve got paint and ladders.’

‘It’s not my writing. You can check.’

‘Clever bastard. No one has ten foot handwriting.’ His hands returned to my shoulders, this time squeezing hard.

‘Have you been hurt by any slags lately, sir?’ asked a pale, earnest constable who looked to be about twelve.

‘Dozens,’ I said, ‘but none in this block.’

Mark’s grip tightened. ‘Where were you last night?’

‘The Puck, The Harp of Erin, The Castle, The Queen’s, The Bedford, The Station, The Armstrong. Then the Karachi. I got back about one.’

‘So you just walked past and didn’t notice it?’

‘You know how it is; you never see anything unless you’re looking for it.’ I put a slight quaver into my voice: ‘I couldn’t have done it, lads. I get vertigo. I can’t go too high since they drained my sinuses.’

All I had to do was keep denying everything. Coppers these days have shorter attention spans. If you can keep them talking for longer than three minutes you’re in the clear: a few at the fringes had already begun to slope off.

‘Did you see or hear anything unusual?’

I thought it best not to mention my re-tied ladders: ‘You know how it is: it’s only unusual if there isn’t something unusual round here.’

As I switched from laughter to a fake coughing fit they dropped me and returned to their vans, slamming the doors and gunning the engines to cover their embarrassment. They’d been overcome by the novelty of the situation: it was only unusually big graffiti, after all. What charges could they have brought? Trespass? Damage to Council property? Threatening behaviour? Nothing quite fitted the bill: they would have to make a new law. I turned to Mark. ‘Whatever made you think it was me?’

‘Well,’ he said, ‘you’re supposed to be some kind of poet, aren’t you?’

I unloaded the van and then checked my shelves. Someone had tidied the place up: the paint brushes were glossy and restored, still slightly wet, and a new tin of white one-coat gloss paint had been left on top of the emptied one. Whoever it was must have been local, to have watched and learnt my trick of freeing the shutter.

| In this | block |

| there lives | a slag… |

| she’s hurt Him | and now |

| she has | to pay… |

I went back outside and looked up at it again: it seemed an awful lot of trouble to have gone to. Only an artist or a signwriter could have done that in the dark without a single drip or tremble, unless they’d clipped on an enormous pre-prepared stencil. Even the dots of the i’s and the ellipses were perfect little circles.

| In this | block |

| there lives | a slag… |

It reminded me of the opening of a song that we used to sing at school. ‘On Richmond Hill there lives a lass/ As bright as any morn.’ I tried humming it but it came out like ‘Old Mac-Donald’: ee–i–ee–i–o.

| she’s hurt Him | and now |

| she has | to pay… |

It’s always a bad sign when you start thinking of yourself in the third person, especially when you give it a capital letter.

Doris, my next door neighbour, had been standing by the main entrance since my return, watching the whole thing. She knew everything about everybody: if there was even a new dog in the pack she wouldn’t rest until she’d discovered its owner and, more importantly, its name. The unusual warmth of her greeting immediately confirmed my suspicion that it was she who had put the coppers on to me. ‘I knew it wasn’t you, love. It’ll be those lads in the seven-fives: they’re all on drugs. Nothing’s sacred to them: they’ve even scratched that new paint off the lift doors. As for the slag’ – she jerked her head towards a group of girls pushing prams up the ramp towards us – ‘It’ll be one of this lot.’

Having obviously decided that if it was to be open season on slags there was safety in numbers, they were advancing in a V-formation, like a motorcycle gang hitting a seaside town, flushed over their usual pallor, shouting at each other as if they were trying to drown something out. They wore tight calf-length denim sheaths that would have hobbled them if they hadn’t extended the fraying slits all the way up the back, allowing clouds of grey slip to billow out behind them like ectoplasm. Their bare legs were scratched, blotched and bruised, red-dotted with fleabites around the ankles. They ignored Doris and just nodded or blinked at me. The prams were all expensive, grey steel and rainbow-canopied, three-braked and togglewheeled, but the babies were thin and silent, with frightened eyes.

They hated children, I’d noticed, but loved babies. They needed something weak and dependent to make them feel strong and in control, keeping kittens until they grew into cats, puppies until they were dogs. They wanted to be babies themselves, to start their own lives over again, or to create happy childhoods that would somehow erase the miseries of their own…but after a while they started to feel even worse than before, under attack from unaccountable creatures that refused to chuckle and gurgle, just shat and ate, got sick and cried, cried, cried. And then the creatures would begin to speak, using words they’d never taught them, asking questions they couldn’t answer. Only blows would shut them up and then not even blows would make them speak again. But after the social workers had taken them away the mothers would bring forth yet another wave of magical babies. A lot of the boys were called Damian: maybe they were trying for the Antichrist.

Doris took the lift: I was up the stairs and back safe in my castle long before she emerged. The sun still filled the bedroom with light, still strangely reflecting in via the same window opposite. Standing on the sill, struggling to hook the heavy curtain back on to its rail, I looked down and registered that every flagstone on the pavement far below was cracked. Stifling in the summer, freezing in winter: it suited me here. I loved to lie on my bed, feeling the block swaying with the winds, listening to the toilet cistern’s whisperings as it took three hours to refill, watching as the ceiling seemed to slowly descend then recede, so that I felt deliciously claustrophobic or agoraphobic by turn.

It had driven my wife crazy, though: everything had been OK until we’d moved in here. ‘I’ve always hated flying,’ she said. Suddenly we were arguing about everything and nothing. All the food she cooked was burnt black or raw. She tried to kill a dozy wasp crawling on the window by throwing the kitchen chair at it. Soon we’d stopped talking altogether: it was soothing for a while, as if we were members of some contemplative religious order, but after we stopped screwing it got bad again – there seemed to be a permanent hissing in the air, like a pan of water boiling dry. The plaster of the bedroom wall was studded with little knuckle rounds from all the times I’d smashed my fists into it – not instead of her or to mortify myself but because I knew that Doris’ ear was pressed against the other side.

The explosion came one Sunday evening as I was singing along with Songs of Praise from Hereford Cathedral, feeling nauseated at the way the eyes of the congregation were opening and closing at the same intervals as their mouths. My wife came out of the kitchen, skidded across the carpet on her knees and turned off the TV. As she turned, straightening up, I hit her, for the first and last time, with closed fist in the face. I pulled the punch but too late, making it more of a twist than a pull. Leaving the ground, she seemed to float horizontally for ages as if weightless, until her head hit the far wall. She lay there motionless. Just as I was working out how to dispose of the body she abruptly returned to the vertical, like a round-bottomed bodhidharma doll.

‘You hit me.’

‘No I didn’t.’

She dropped her hands from her mouth: her teeth were etched in scarlet. ‘Oh yes you did.’

‘It was lightning’ – I gestured at the placid grey sky – ‘A miracle: a ball of lightning rolled in, knocked you over, then left by the keyhole. Let that be a lesson to you: come not between man and his redeemer.’

She leaned forward and kissed me, hands fumbling for my zip. I tasted blood and gin: she’d been hiding the bottles again. It felt as if I’d knocked her upper front teeth out of alignment but she insisted that they’d always been like that. For the next few days it seemed as if that one blow had somehow broken the spell. We couldn’t keep our hands off each other, we laughed and chattered as if we’d just met – but then she was gone without leaving a note, taking only her clothes. I hadn’t heard from her in the two years since: Doris, I knew, was saying that I’d buried her somewhere.

I went into the living room and picked up my dad’s old dictionary: it stood where the television used to be. SLAG: I looked up the word. It came from slagen, middle low German, meaning to slay. ‘Has many senses or nuances, all pej’. Pej, I decided, could only be an affectionate diminutive for pejorative. It wasn’t only a slattern or a prostitute, then: it could also mean rubbish or nonsense. It was a limp, a watch-chain, a bully or a coward; flux, scoria, gangue, pyrites – whatever they might be – silicates or pigs. It was soft moist weather, a quagmire or a slough. It was to pain with severe criticism: to lag, to idle, to spend recklessly or eat voraciously. It was a dottle: dottle! What a wonderful word! It meant the unburnt remnant of tobacco at the bottom of a pipe bowl. I’d kept my dad’s old black bone briar: if I put it to my ear I’d seem to hear the distant echoes of his coughing, if I stuck my finger into its bowl I could feel something rough at the bottom – the last dottle, his soul. Language is power, he used to tell me: if you know a word it can’t hurt you – which was strange because I was pretty sure that he’d known the word cancer.

A slag was carny slang for a punter who looks at the free attractions but avoids the paying shows. In Australia it meant to spit. A slagger was a brothel-keeper; a slaggering was a row – but was that a great commotion, a trip on a lake, or a line? It meant unwashed, useless, a petty criminal, a third-rate grifter. It was a slack-mettled fellow, one not ready to resist an affront…the word seemed to encompass everything. I myself was a slag, living in a city of slags – in a country, a world, a universe of slags, in an infinity of pej.

On the way down to Park Road for milk and bread I decided to stop for a quick pint which meant of course that I never made it: beer was a food anyway. Having been gutted to create one huge circular bar, the place had recently reopened, now designated a Fun Pub, renamed The Puck after its randomly chosen ice-hockey theme, with netting and sticks depending from the frosted ceiling and rows of goalminders’ masks staring down like Jason Vorhees in Friday the Thirteenth. But now the regulars were gradually drifting back like wraiths, smothering any Fun in its cradle. The new green-on-red carpet was metamorphosing into its predecessor – ash-grey and polka-dotted with brown and black burns – and the gleaming bar already had a layer of dust that wouldn’t brush off. I wondered if the extirpated partitioned snugs and games-rooms would just grow back, like branches of a lopped tree.

Without my even asking, Eleanor the barmaid slammed a plateful of clingfilm-wrapped egg sandwiches in front of me. ‘Leftovers from yesterday,’ she said, but they tasted far too fresh for that, with fine-chopped onions and home-made lemon-based mayonnaise. Her eyes, perhaps distorted by the thick lenses of her glasses, always looked to be full of tears. Everybody seemed to think that I was starving but all I ever did was eat and drink.

All around me, people began to just materialize out of their chairs. The usual conversation began: football, always football. I tried to convince myself that I found this familiarity comfortable. They were still picking over the Barnet game: I’d been there and couldn’t remember a thing about it. Only triumphs and disasters registered with me, which meant that the whole season had been a virtual blank. I couldn’t bring to mind the names of any of the current City players: they were all the same, with no first touch, donkey haircuts and unfocused eyes. The old ones – Rackstraw, Corner, Swallow – I used to dream about them, even though they were crap.

‘This club’s got no ambition, taking that Tolson off Oldham in part-exchange for McCarthorse. They should have held out for Sharp, or Beckford, or Palmer.’ Dave could tell you any football fact: his bed-sit was piled to the ceiling with red Silvine exercise books full of statistics. He knew more about the game than any player, manager or journalist ever could: they had distractions – wives, children, food, sleep – but with him it was his entire life.

Whenever a woman came in silence fell, followed by a hubbub of fevered speculation. Which one was the slag? Naturally, the three best-looking were the favourites. Was it the grey-haired one? There was something sinister about her: although she had four kids – two in the army – her face was still unlined and her body remained as tight as a sixteen year old’s. Or the crop-haired one? She was never seen with a man so she could only be a lesbian, the wrong kind of slag. Or the little blonde? Her husband’s legs had been shattered at Forgemasters’ and she had to help him along like a third crutch while he cursed her: it was said that she took home three different men every night but no names were ever mentioned. Huddling together, even going to the ladies’ in pairs, all the candidates looked too hesitant and frightened to me. The Slag should have remained unconcerned or, at least, defiant – peroxided, mad-eyed, meanmouthed under a scarlet lipstick bow, with the names of her victims tattooed from shoulder to wrist…Finally Dave broke off his unheeded monologue on City’s left backs of the last two decades. ‘It could be any of ‘em,’ he growled. ‘All women are slags.’

‘What, every last woman in the world?’

He thought hard for a few moments: ‘Nay, round here. I only know round here.’

I noticed that all the men were looking at each other with furtive, complicitous expressions that tried to say at once ‘It was me’ and ‘I know it was you’. The women were doing the same. It was as if war had been declared but The Puck was still – just – a neutral Zone.

| In this | block |

| there lives | a slag… |

| she’s hurt Him | and now |

| she has | to pay… |

If there was any way out of this entire mess I’d always felt that it must have been something to do with women – although in my life they’d invariably only made everything worse. I wondered if The Slag didn’t even know she was The Slag and was getting on with her life unawares. Maybe she’d hurt Him by not noticing Him, by remaining entirely unaware of His existence?

If you really put your mind to it you could be hurt by anything. I’d spent all the previous summer watching from my window the arrivals and departures – at 8.10 and 5.05, Monday to Friday – of a girl who, to avoid the NCP toll, used to park her blue Volvo on the slip road below the garages. Tall and dark with a long pony tail, she was always dressed the same: black soft leather jacket zipped right up with tight moleskin trousers tucked into high-heeled green half-boots – I always liked people who settled on a look and then stayed with it. When it rained she held an umbrella with her arm fully extended and a dead straight line of neck and back, like Mary Poppins. Her car gave no clues as to which district she came from or where she worked: no dealer’s flash in the window, no clothes or books on the back seat, no cigarettes or sweets in the dashboard, no mascots or fuzzy dice, not even a radio so I could see what station she listened to. Its windows and bodywork, though, were always scrupulously clean.

Although I must have been invisible to her as I stood far above in the darkness behind nearly closed curtains, she often paused and, shading her eyes, looked up in my direction. Although her figure far below was tiny I could discern the colour of her eyes – somewhere between blue and green – read ‘AERO’ on the catch of her jacket’s zip and pick out on her back pockets the strainings of every single white stitch. I sometimes considered waiting around down there – to smile, strike up a conversation or follow her – but I never did: I liked things just the way they were.

Then, one lunchtime, as I lurched, refocusing, out of The Ram’s Revenge, I literally bumped into her. Laughing, she steadied herself with one hand on my shoulder. My mind raced, trying to adjust to how she’d suddenly blown herself up from half an inch high to – in those heels – slightly taller than me. Although she didn’t need it, she was heavily made up. It couldn’t conceal a cold sore at the side of her nose – my fingers automatically scratched the same place on my own face. Our eyes met and then her smile twisted into an expression of horror or disgust. She turned white, then beetroot-red, then ducked her head, clutched her boxy handbag as if it had been a threatened baby and went clattering and stumbling down the steep cobbles of Ivegate.

I stood there frozen. It was as if with that one look she’d taken in everything about me. How could she believe any more in her guardian angel on the seventh floor now that she knew that he was waiting for her every morning and evening, unzipped and ready, with a wad of Kleenex in his hand? On the way back to the block, without premeditation, I kicked-in her car’s passenger door. At five past five she stood with hands on hips and stared straight up at my window for a full two minutes before getting in and driving away. She never parked there again. It felt far worse than when my wife went, as if I’d destroyed the most important relationship of my life – but I didn’t think of her as a slag, just as I hadn’t blamed my wife for liking or not liking being hit. Probably I was no kind of man at all.

As soon as the quiz started I left The Puck: The only question that interested me was ‘What are you drinking?’ The craze would soon pass – like striptease, karaoke or stripkaraoke. Even on a Friday evening the city centre was deserted and silent, except for the starlings screaming from the roof of the Town Hall – the pavements below them were whitened over like snow. Every attempt to get rid of them – birdlime, nets, ultrasonic sound, hawks, stuffed and real – had failed. I loved Bradford at night: I felt light-headed and freed, like one of those kings who would roam unrecognized among their subjects – I never bothered with a disguise, though…leaving off my crown sufficed.

The Royal Standard, The Gladstone, The Peckover, The Perseverance, The Junction – most of my favourite pubs had been closed down. I ended up in The Shoulder of Mutton, drinking sweet weak Sam Smith’s, alone except for a muttering lunatic who Eleanor, good Catholic, had recently banned from The Puck for insisting that Mary Magdalene and the Blessed Virgin had been one and the same person.

In my teens I scoured Bradford for the perfect pub. I used to see it in my dreams. The interior somehow combined patches of blazing white light and impenetrably dark shadows; it had a fifties jukebox with ‘Let there be Drums’ and ‘Endless Sleep’ on it. The landlady resembled Eleanor – but without the religious fanaticism – and although the landlord was permanently drunk you never needed to count your change. It served Taylor’s bitter, had Powers & Bushmills’ optics and Ram Tam Winter Ale on all year round. It was always packed, with good company when you needed it that didn’t need telling when you didn’t. There was no gossiping or talk of football. Search as I might, I’d never found it, but even twenty years later if I stayed in one place for more than an hour I still started to get restless, to feel that I should be out searching, that maybe there was one street that I’d missed. That was how I’d come to be a regular everywhere.

I used to hear tales of a group who I suspected of being on the same quest as myself. There were three men – one fat, one medium, one thin, one fair, one dark, one shaven – who, so it was rumoured, ran a waste disposal business together. Drinking didn’t fuddle them but inspired them: they’d argue brilliantly and interminably about everything under the sun. They weren’t universally popular, though, as they had a curious habit of killing any animals that were in the pub. Beautiful women – always different ones – were said to attend them, ferrying the drinks from the bar while themselves nipping from garnered hip-flasks as they waited to be served. Sometimes I just missed them, entering a pub that was still rocking with laughter as a grinning landlord cleared up the broken glass and splintered wood. Once I found the body of a mynah bird, torn out of its cage and throttled, still quivering on the counter. I never did catch up with them. I’d wondered whether as I sought them they might also have been seeking me, so I’d forced myself to spend entire evenings in one likely place but they were probably sitting across the street doing the same thing.

When The Lord Clyde closed I walked back through the still empty city. Even the starlings were quiet now as I crossed Town Hall Square and climbed towards the Central Library’s block of misted-over glass. On alternate windows large red words had been placed to spell out the lines:

HE WHO BINDS TO HIMSELF A JOY DOES THE WINGED LIFE DESTROY BUT HE WHO KISSES THE JOY AS IT FLIES LIVES IN ETERNITY’S SUNRISE.

It was OK but nowhere near as good as ‘In this block…’ On the ground floor slightly larger green capitals revealed the name of the author: BUTTERFIELD SIGNS. I passed the slate-grey statue of J. B. Priestley, depicted as part-golem, part-monkey, with his feet firmly planted against an eternal force nine that had ripped open his flasher’s mac to reveal him to be frigging the slender stem of his trademark pipe. In Bradford we never forgive the ones that go…or the ones that stay.

I crossed the empty tarmac, walking the white lines that had been marked out as spaces for cars that never came, then negotiated the ghostly six-lane cross-town ramp that linked nowhere to nothing, to reach The Karachi. Everyone I knew seemed to hate the Asians but to me they were angels, sent like Elijah’s ravens to sustain me. In fifteen minutes I had consumed a poppadum, meat samosa, onion bhaji and chicken karahi at a cost of £3.50. Who cared what they wanted to do to Rushdie? – after that meal, I’d have dragged him in there and helped them to bhuna him myself.

Around the blocks up ahead it seemed as if a lunar glow from the painted letters was outshining the streetlamps’ yellow light.

| In this | block |

| there lives | a slag… |

| she’s hurt Him | and now |

| she has | to pay… |

The writing on the wall: it was like Belshazzar’s Feast. I pictured a disembodied hand crawling across the building like an enormous snail, sliming its white trail: MENE, MENE, TEKEL UPHARSIN – ‘Thou art weighed in the balance and found wanting’. It had always seemed unfair to me: all the other miracles in the Book of Daniel had been to protect the Israelites or at least to keep their spirits up but this one was sheer cruelty. As poor old Belshazzar would be dead within a few hours, with no time to change his ways or even express contrition, what was the point of telling him, except to gloat?

I remembered a nursery rhyme that my gran had taught me:

‘How many miles to Babylon?

Three score miles and ten.

Can I get there by candlelight?

Yes, and back again.’

Babylon: the mother of harlots and abominations of the earth – I’d always wanted to go there. As a kid I used to check the departure boards at Forster Square Station but it appeared that there were no direct trains.

Babylon: last year I’d had a three-week plastering job down in London. My workmates were Cockneys who kept waving rolls of banknotes in my face and spitting to just miss my feet but I only smiled and called them all ‘love’ – it drove them crazy – while setting up a series of little industrial accidents for them. Otherwise I mostly slept in my van in the garage off Malet Street, except for Sundays which I always spent in the National Gallery. I liked those big fleshy Rubenses and the very old ones with dusty wooden doors but after a while I just walked straight past them to gaze at one painting, Rembrandt’s ‘Belshazzar’s Feast’.

I could still recall its every detail: a bowl of nectarines and grapes with a little gold and silver fruit knife, Belshazzar’s gut splitting open his waistcoat, his bitten fingernails, the crown perched absurdly on top of his outrageously tasselled turban. In turning to follow the progress of the glowing hand he upsets his goblet: The spilling wine is yellow, as if he’s pissing himself with fear. His women aren’t looking at the hand but at him, to see how they ought to be reacting. One girl, part-obscured by the others’ plumes, remains oblivious, still playing her recorder, cross-eyed with concentration as she goes for that tricky low D.

The real attraction for me, though, was that Belshazzar looked exactly like Kenny Burns, the fearsome centre-half from Nottingham Forest’s cup-winning team. As a veteran, dropping through the lower division, he’d played for Derby against City in our promotion season. Flabby and pale, with a crosshatched moustache and a layered haircut in need of darning, he cruised his ten square yards of pitch, dead-eyed as a shark. No one dared go near: even Crazy Bobby Campbell wouldn’t take him on. At one-all, late in the game, we brought on our teenage substitute, Don Goodman. ‘Oh God, here comes the headless chicken,’ Dave said. Goodman was lightning-fast but wildly uncoordinated, usually falling over in his sheer excitement whenever the ball went near him. This time, though, receiving his first pass, he managed to stay on his feet – he turned smartly and headed straight towards Burns’ sector. We cringed, awaiting the inevitable terrible impact…then, at full speed, Goodman feinted right and left then, having thus opened Burns’ legs, slipped the ball clean through them and went by him like the wind. In Rembrandt’s picture I relished again Burns’ horrorstruck expression as he’d turned to see Goodman, already twenty yards on, lobbing the keeper for the decisive goal. That win had put us top: we stayed there for the rest of the season.

I used to look at it for hours with the gallery attendants watching me like hawks. They knew that my presence – a man in stained overalls, his hair weirdly full of unmelting snow in mid-July, standing in front of a painting, laughing wildly – must be against all the regulations but – like the coppers with the big graffiti – they couldn’t find anything that covered it. I became aware that I was laughing again now, standing alone in front of my block. Goodman and Burns: it hadn’t been about football or even about how the old fall prey to the young, it had just been a perfect moment…an utterly unexpected intrusion of pattern and grace that had set off simultaneous explosions of somehow sugary warmth in my head, heart and gut, like when I’d stood by my window watching the stitched chevron of those back pockets moving around on that tight white arse far below.

| In this | block |

| there lives | a slag… |

| she’s hurt Him | and now |

| she has | to pay… |

Since the afternoon the words seemed to have slid down the wall as if to create space for further bulletins. I felt that there was something about all this that I wasn’t quite getting, as if it was a code that I couldn’t crack – as if, on some other level, it had nothing to do with blocks and slags at all. When I closed my eyes I found that the letters were still visible on the red field of my lids.

There was a roar of approaching engines and then a loud squealing of brakes from behind me. At first I thought it was the boys in blue returning for a second shot but these three grille-windowed vans were smaller, blue and gold with Graffiti Removal Unit painted on the sides. The dozen men who came spilling out were all wearing balaclava helmets and dark uniforms with epaulettes and what appeared to be cartridge belts. Some of them had thick droopy moustaches like seventies TV detectives. They jogged past in step, in two precise lines, bearing gleaming steel ladders above their heads. Within thirty seconds they were high above me, scrubbing away at the side of the building.

The Council didn’t usually react so quickly – or at all. Most graffiti was just left well alone: my own favourite – WEBBO/VICIOUS/JEDI – still remained on the railway bridge – in its proud but fading letters of dripping scarlet lake – after fifteen years. Someone powerful had obviously found ours – whether because of size or content – unacceptable. Perhaps there were hundreds of such notices all across the city that were being immediately erased, with all reports suppressed, like they do with UFO sightings.

The sprays and brushes couldn’t shift the letters, so the men had to return to the van for their pressure hoses to blast them away. One of the moustaches ran so fast that he overshot and, in trying to turn, tripped and crashed to the ground. I gave him a mocking slow hand-clap and slurped my tongue round my lips. ‘I just love watching men at work,’ I said. He didn’t reply or even react, just strapped on his hose and shot back up his ladder. I was looking for a chance to make off with a bucket or torch, but then realized that a thirteenth man had remained by the vans with a mobile phone, mumbling incomprehensibly to somebody. Aloft, they worked on in total silence, \\ flat out. I couldn’t stand these new model working men. No talking, no tea or toilet breaks, always running, never walking – if the Council had tried that on when I started on the bins twenty years ago we’d have had the whole city out on strike. We used to work at half the speed for half as long: did we think the world owed us a living? – No, we knew it did. For working on Friday, after midnight, this lot were probably getting only time-and-a-half, at best.

Some of them were working inwards:

| n this | bl |

| ves | a s |

– While the others worked outwards:

| she’s h | ow |

| she | ay… |

Although I knew that they shared a shabby Canal Road hut with the dog-wardens and pest-controllers. it appeared that the GRU wasn’t merely another council department but something sinister, even supernatural. As I watched, it seemed as if they were ruthlessly wiping the words from my memory, as if I’d awakened in the middle of the night to discover them standing around my bed, sandblasting away my dreams, I felt sick and giddy, as when I’d once rested against the electric fence at the edge of a field of cows and thought it had been God’s hand that had struck me down. There was a strange ticking sound that I finally decided could have only been the knocking of my knees. Up until that moment I’d thought this to be merely a figure of speech: maybe my hair would have been standing on end as well, if my head hadn’t been shaved – or rather, bald.

Even when they finished the men didn’t relax, marching silently and expressionlessly back to their vans without looking at each other or at me. I didn’t turn around to watch them go, just continued staring at the empty wall. I was pleased to see that, in their haste, they’d missed the final dot, bottom right. I hoped that the words might also begin to reconstitute themselves but nothing further appeared. I’d always thought that my block was grey but now there was a golden, star-shaped patch where the letters had been. At least our prison had been built of the finest Yorkshire Sandstone. I realized that I was able to recall the words in two halves, by concentrating on the rusting drainpipe and shutting first the left eye:

| In this | |

| there lives | |

| she’s hurt Him | |

| she has |

and then the right:

| block | |

| a slag… | |

| and now | |

| to pay… |

– and then combining them.

I walked up close to look at that sole surviving dot. It hung about ten feet off the ground: I jumped up a few times but even with arms fully extended couldn’t quite reach. It was a perfect circle, slightly larger than my own hand, like the porthole of a ship.

I leapt once more and this time my finger-ends slapped against the whitened stone. Nothing happened for a moment and then it was as if I’d touched the button that opened some cosmic portal, as the hungry hole rapidly hoovered up everyone and everything. They all went past in a blur: a daisy-chain of coppers, Cockneys and GRU, then Goodman and Burns laughing together, Eleanor and the apostate, Doris and my wife, the innocent slags with their prams, a perfect arse and a pony tail…the pubs, The Karachi, the house in Thornton – despite its new slates and guttering…the Town Hall, the library and all its books…all the words in the world and all their meanings. Then there was no glass or grass under my feet anymore, no stars or moon, no light or darkness…I was suspended in nothingness for an instant but then – just as I was beginning to fret over why I’d been excluded or spared – everything and everyone came spewing right back out again…