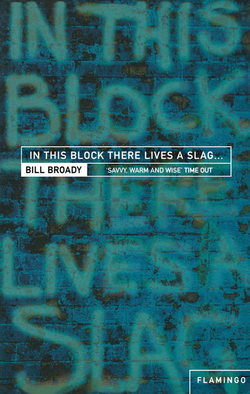

Читать книгу In This Block There Lives a Slag…: And Other Yorkshire Fables - Bill Broady - Страница 8

Songs that Won the War

ОглавлениеRadiation salvoes, for a while, had held the cancer at the left lung, but then supposedly arthritic side-effects were revealed to be an all-out offensive on the spine that hadn’t – for some reason – shown up on the scans…Hopeless, so they moved my father from infirmary to hospice.

I was glad to see him out of there. When I’d heard talk of NHS demoralization I’d imagined longer queues in casualty, higher levels of sickness and staff turnover, more snapping and sighing, undusted window ledges, the odd mislaid corpse: I wasn’t prepared for the hospital’s descent – in the five years since my mother died – into an abyss of unfocused fear and hatred. Compassion and competence had been shut down along with the dark, echoing dermatology wing. A series of specialists – with half-moon glasses and gold pinky rings – sidled up to rubbish each other’s prognoses: an endless Tom and Jerry dialectic, until the disease itself shut them up. Half the housemen were German, over on cheap short-term contracts: one of them had prodded my father’s chest, where the blue-black shrapnel seemed to swim subcutaneously, like fish in a silted-up pool. ‘Vere did you get zis?’ he asked in best Gestapo fashion. ‘Narvik 1940’ – my father rolled his eyes – ‘Your lot.’ He didn’t forgive: the last real animation he’d shown was in punching the air when Lechkov’s bald head put Klinsmann and Co out of the World Cup.

The nurses were even worse. Vampire-pale, stony-eyed, at visiting times they moved from bed to bed, weirdly vibrating, avid for the drama and tears: the ICU was better than East Enders or Corrie. They hated my father for grimly recording each cracked window, jammed radiator and empty light socket, every little oversight and cruelty, everyone’s names: after his red Silvine notebook had mysteriously vanished he hid its replacement inside his pillow. They hated me for my lack of obvious grief: my diffidence cracked just once – when they offered me pre-bereavement counselling and I burst out laughing. After that, eyes averted, they stumped past us, as if crushing hideous vermin under their thick soles. Whatever happened to the bow-tied doctors who used to work the wards like game show hosts, the ward sisters like opera divas, the Hattie Jacques matrons? Whatever happened to the student nurses of my youth – vivid, tender, blithe as spring throstles and self-parodically hot to trot…though seldom with me?

The hospice was high above Wharfedale, the last house before the moors. As I left the car I got, as always, a tang of ozone, although a hundred miles from the nearest coast. It was a wool baron’s Italianate mansion, converted, ringed by immaculate parterres, pulsing and blaring with crude life and colour: where were the bosky, bowering cypress and yew? The residents were never seen outside, though today I glimpsed lemur-like flittings in the sunporch shadows.

The hall’s darkness enveloped me like squid’s ink and I groped towards the window lights’ tiny lozenges at the top of the mock-baronial staircase, toe-kicking each invisible riser. Halfway up, the Pain Management Team – three grinning boys in luminous white, like a tumbling act – passed me in mid-air, breasting the front door with one more kangaroo bound. The oak bannister I’d cowered against was strangely warm and yielding: time rubs off hard edges, makes things kind – old buildings are the best to die in, or die into. ‘It’s bad luck to be the first to die in a house,’ my grandfather had said, just before he was.

My favourite nurse was on station: the one who, by nightlight, had rubbed my father’s back with toothpaste instead of muscle relaxant and hadn’t stopped giggling about it since. Above the ligature-tight chain of her St Christopher her soft, wet face beamed perpetually on her ‘ressies’ – as if, in dying, they were essaying some much-loved party piece. She winked and wagged her finger at me, knowing that I carried a whisky bottle in my poacher’s pocket. She’d got my number: a dinosaur, whose pain took an age to reach heart or brain. It had been three months after my mother’s funeral when, traversing the ridge away from Ingleborough, I looked back to recognize, in the mountain’s beetle-browed profile, her dead face.

My father’s grey hands lay in a plate of untouched food. On the white traycloth was a line of crimson splashes – lung blood – like a restaurant critic’s five-star recommendation. His pills were laid out ready – the doomed fleet he was about to launch on his bloodstream. His eyes opened and his arms elongated to reach the t-bar above the bed, to give the illusion that he was raising himself in welcome, his fingers fluttering on the metal like a flautist’s. The more he wasted away the heavier he got: it took two nurses to cross-lift him, tightening a plastic sheet or straightening a pillow were major undertakings. His head looked to be getting larger, doming, with a strange metallic sheen: his arms seemed to retract into his sides, his legs to fuse: it was as if impotence and anger were turning him into a lethal projectile, a shell in the breech ready to be fired into the infinite.

I gave him a slug of Chivas Regal and poured the rest into his empty lemon barley bottle. ‘Ah, Jeepers Creepers,’ he said, ‘Jesus Lethal!’ – he always pretended to forget its name – ‘Still, you don’t have to be able to say it to be able to drink it.’ He rested his bristled chin in the plastic drinking trough, as if taking the liquor through his pores. I’d turned him on to Chivas in those days when in every bad, bold photo of the Stones Keith Richards seemed to be finishing a bottle.

I’d swapped my Red Army watch for the huge self-winding Timex, dying on his motionless wrist, that now slid, its metal strap ripping out hairs, along my arm. The fluorescent hammer and sickle seemed to be affecting him – he spent the last of his strength on raging against capitalism. Or maybe it was a symptom of the cancer or his finally admitting the anger he’d always felt. I remembered watching Tebbitt, white-plastered like a pierrot, being lugged out of the bombed Grand Hotel and, as his teeth bared in an equine grimace of agony, I had seen my father respond with one of his rare smiles. It obsessed him that it was the Navy – out in The Falklands, with inadequate air-support – that had saved Thatcher’s bacon: that the dead sailors of the Sheffield – ‘Rejoice! Rejoice!’ – had bought her two more terms. He told me that after VJ Day, when he was CPO on a carrier ferrying ex-POWs out East, the demob-happy crew had stopped saluting and taken to calling each other ‘Comrade’. The Captain had asked him whether his life would be safe when they got back to England. After my father had reassured him they’d shaken hands and toasted the future with rum – but the ship’s postal election votes were still mysteriously lost in transit. At the time they’d all laughed at their officers’ ludicrous fears of mass purges and seizures of assets: ‘But now,’ he said, ‘I wish we’d done just that.’

As my father had observed, his ward was like a convention of Delius impersonators, copying the James Gunn portrait of the dying composer – right down to the tartan blanket over the knees, the fleshless left hand gripping an arm-rest, the right pointing to the floor. Even Mr Siddiqui – wrapped in the pearly aura of death – somehow pulled it off. In the next bay was a kid of no more than twenty, spending his last days reading Coleridge. Impossibly attenuated, his extremities jumbly-green and blue, he lay among propped-open copies of Biographia Literaria, the poems, the letters, volume one of Holmes’ Life – he would never read the second. He hadn’t been amused by my father’s rendition of The Ancient Mariner or my tale of chickening-out of following the mountain-mad poet’s series of ledge-jumps down Broad Stand. With heavy emphasis he slowly dragged his bed curtains across, breath singing in his throat like an Aeolian harp.

I gave my father the latest bulletin on Halifax Town – kicked out of the league to the hospice of the Vauxhall Conference – and told him how the cheating kraut Klinsmann had signed for Spurs and, after a series of spectacular goals followed by ironic swallow-dive celebrations, become a national hero. He looked reproachful, as if such jokes were out of order at this time. We sat in silence. There wasn’t much I could do for him – just bring in whisky, swap watches, lend him my Walkman and Jelly Roll Morton tapes. I could give him no handy hints for the afterlife unless, God help us, ‘The Divine Comedy’, ‘The Human Age’ or ‘Hellzapoppin’ proved to be reliable guides. Stephen Crane wrote of ‘the impulse of the living to try to read in dying eyes the answer to The Question,’ but I didn’t have any questions, not even lower-case ones.

He flapped his hand towards an unopened jiffy-bag on his table. I prised out the staples with his fish-knife. A video cassette fell out, followed by a postcard of the Bismarck on fire, with the message, ‘Hope this cheers you up and reminds you of those good times – STAN.’ They’d been boy sailors together on HMS Ganges – ‘and he hasn’t changed,’ my father always said. Stan’s spare time was spent at reunions, the Navy was all he ever talked about – my father pitied, despised him: ‘The war’s never ended for him, like those Japs they keep finding in the jungle.’ Now he just rolled his eyes and sighed. I’d known little about his own war: as a child I’d found, worn and lost his medal ribbons…once he’d casually mentioned that the shrapnel roaming his body had first passed through that of his best pal.

I held up the video. Songs that Won the War: on its cover searchlights over a blitzed London picked out the enormous grinning face of Vera Lynn about to snap up a passing Heinkel. He rolled his eyes again, spoke faintly. I put my ear to his mouth, then rocked back deafened as he near-shouted, ‘Put it on!’ I wheeled the TV over: static electricity crackled as I dusted the screen – like a cat, it knew I didn’t like it. I’d dumped mine, though when I went to my ex-wife’s to babysit I’d take along my Buster Keaton videos.

A perfect English sky was invaded by an anvil-headed stormcloud, from which issued the voice of Neville Chamberlain: men and women broke off from pipe-tamping or knitting to present resolute profiles. Then Vera Lynn appeared, sitting in an empty theatre – ‘the girl they left behind.’ ‘The girl we were running away from,’ said my father. She smiled thinly: ‘We are a nation of backbone and spirit, so that when we were forced into war in 1939 there was no fear in our hearts.’ ‘No, we just crapped ourselves,’ said my father. It cut to her singing fifty years earlier – looking older, if anything – her awkward hands rinsing and stacking invisible washing-up, in what looked like the garden set of L’Age D’Or. ‘Johnny will go to sleep in his own little room again…Tomorrow, just you wait and see.’ ‘Well I’ve waited,’ said my father, ‘and I’ve seen.’

A cruiser slid out of Pompey Harbour: most of the crew were waving to the crowd – parents, wives, children – but as the camera jerked away I glimpsed a sizeable number to starboard greeting the open sea. I think that’s the side my father would have chosen: our family holidays were always littoral – he’d sneak out hours before breakfast, as if to meet a lover…Then the whale-like calls of signalling ships segued into the voice of Our Gracie. ‘We’re all together now…’: she approached the audience, transfixed as by the lights of an oncoming lorry, like someone trying to coax out from under the sofa the last puppy to be drowned. ‘Whadda we care?’: she did a little dance, as if shooing chickens, reminding me of Mrs Thatcher.

Forgotten songs, forgotten singers. George Formby, his cod’s head emerging from the best-cut suit I’d ever seen, strummed and gurned in front of a curtain seemingly painted with tantric demons. Flotsam and Jetsam sang how London Could Take It, a majolica vase perched on the piano presumably demonstrating the ineffectiveness of The Blitz. Churchill appeared among bombed ruins, in a romper suit, sucking at his cigar, a behemoth baby. ‘We weren’t fighting for him,’ said my father, ‘we remembered Tonypandy and the British Gazette. We were fighting for the peace – jobs, education’ – he shrugged – ‘a health service. A better society, before Thatcher told us there was no such thing.’ The video had certainly livened him up, though not in the way Stan might have intended.

Flanagan and Allen sang ‘Rabbit Run’ over the celebrated film of a Spitfire tracking a German bomber, while below, on a Cotmanish field, a lurcher chased down a rabbit: for a few dizzying seconds animals and machines moved from left to right in perfect synchronization…Then the anaesthetic washes of ‘String of Pearls’: the Glenn Miller Orchestra was bombing Pearl Harbor. America’s entry into the war involved a great improvement in musical quality – Dinah Shore languorously exploring ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’ – and colour film – the Andrews Sisters exploding in their crimson dresses. ‘I always fancied that middle one,’ said my father, ‘the double-jointed one that could scat.’ In comparison with this released New World energy the Home Front looked drab and costive, the stock fading to saffron, the confused crowds at railway termini half-obscured by London particulars or dragon clouds of smoke from their perpetual Woodies and Cappies.

Then a ribald fanfare sounded: into a mob of sailors, milling about below decks, there descended an enormous chin – Tommy Trinder, in uniform, kitbag on shoulder, head cocked, was coming down the rope and chain ladder. Having surveyed the scene with a nod of satisfaction, he began to sing:

Of all the lives a man can lead

There’s none that’s like a sailor’s

It’s very much more exciting

Than a tinker’s or a tailor’s

He leaves his home sweet home

It seems he loves to roam…

He got lost in the bustle, kept approaching the wrong berth and being pushed away. His grin got wider. He approved someone’s pin-up with a raised thumb, then attached himself to a passing close harmony trio, a cerberus of raffish cockney grifters:

…All over the place

Wherever the sea may happen to be

A sailor is found knocking around

He’s all over the place!

Trinder moved in an absurd yet hieratic glide, like something obscurely sinister in a Kenneth Anger movie, his profile like the elongated eye of Horus gripped in the vice of brow and cheekbone:

The North and the South

The East and the West

There’s half of the world

Tattooed on his chest

And all over the place!

Then a scanty-haired dodderer began to intone the signal before Trafalgar – ‘England expects that every man today will do his duty’ – only to reel away from his shipmates’ volleys of pillows, boots and brushes. His crew would have done that to Nelson too if they hadn’t loved him – as my father always said – because he upped their grog ration, fought polar bears, chased beautiful women and was clearly, heroically, off his head.

He’s here for a day

And then he’s away

He’s all over the place!

The music burst into a hornpipe and the sailors danced, wildly stamping on the decks. I imagined the officers up top getting nervous, hearing in that satyr rout their approaching nemesis, the revenge of the subhumans, revolution…only to be confronted at the last not by bloody Jack Cade but by Clem Attlee in his MCC tie.

He’s here, he’s there, he’s everywhere

He’s all over the place!

Tommy waved a huge baton over the swell of sound but kept delaying the climax: ‘He’s all over the – wait for it! wait for it! – place!!!’ After the last chord someone crashed a folded deckchair over his head but his ecstatic smile didn’t waver.

I pressed the freeze frame. My heart was pounding, I was running with sweat, like the first time I heard ‘Anarchy In The UK’ or ‘Straight to Hell’. My father clapped his hands: ‘That’s just how it was! Everyone went a bit crazy at sea, the best sort of crazy…I’m sounding like Stan! I mean it was fine if you didn’t mind the blood and guts.’

We rewound ‘All Over the Place’ and watched it again. My father recalled that it came from a film, Sailors Three, identifying the old man as Claude Hulbert and the young sailor with a mass of oiled curls as Michael Wilding, who married Liz Taylor. Senescence and youth flanking Trinder, the man: grandfather, father and son united in a magical triangle – all over the place, coffined in steel, with a head height of twenty feet…In the song’s final chorus it was obvious that they were surrounded by real sailors with bad skin, gappy teeth, tufting hair – chums with their arms around each other’s necks; their gaze, bold but shy, followed the camera as it swept by: I felt a jolt of contact as their eyes met mine, as if their souls were living on inside the celluloid.

We saw Trinder once, my father and I: at one of my first Halifax Town matches. When Fulham, led by the great Johnny Haynes, aureoled in brylcreem shine, scored the sixth of their eight we heard the unmistakable voice of chairman Tommy, his catchphrase, ‘O you lucky people!’ booming above our faltering cries of ‘Come on, you Shaymen.’ And my father remembered him guesting on the TV game show, The Golden Shot, rocking with cruel mirth as a sobbing Bob Monkhouse recounted the contestants’ increasingly heartrending and hilarious hard-luck stories, so that, unable to hold the crossbow steady on the prize target, he’d pinged the bolt into the studio ceiling.

‘I saw that!’ said Mr Siddiqui, who’d tacked gingerly across the ward to join us. ‘Bernie, the bolt!…Ann Ashton, the Golden Girl!!’ – he looked heavenwards, as if expecting her to appear.

The sound had drawn the ressies from the other wards. Even the smoking room emptied: a fat grey man covered in ash who I’d never seen before crashed down on to my father’s legs, but he didn’t seem to mind. I rewound it and played it again. And again. They began to tap their feet and to hum like drowsy bees and then, gradually, we – eleven dying men, the toothpaste nurse and myself – began to sing and then – on the slack, echoing lino – to stamp. The Pain Management Team appeared and started working out the hornpipe steps. My father – his hands steady again – was pouring everyone hits of Jesus Lethal into the bottle-cap.

The curtains around the next bed were thrown aside to reveal Coleridge in wrath at this army from Porlock that had apparently arrived. Index finger poised for the ‘off’ switch he shuffled agonizingly towards the screen, but then stopped as I froze Tommy again in that final transfigured pose. His face moved right up to Trinder’s, as if getting his scent. ‘That man,’ he said, ‘looks like a camel.’ At the volleys of laughter that greeted this he blushed, blood rushing back into his face, then smiled – his mouth widening and widening until it hit the jaw line – ‘A Bactrian.’