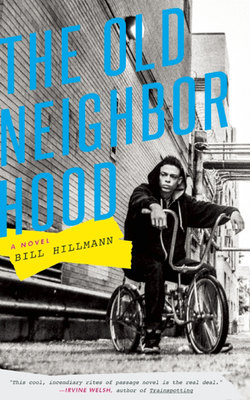

Читать книгу The Old Neighborhood - Bill Hillmann - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

THE MUSCLED-UP, NAVY-BLUE ’65 IMPALA sat elevated on ramp jacks above the white slab of the two-car garage. Pungent oil spilt in a steady bead to the tin pan below. You watched it empty as you crouched beside the car with your head craned downward. Your long arms stretched down—hands planted flat on the concrete. The veins bulged and crisscrossed the bulbous knots of your forearms like strings of lightning.

The garage door burst open, and a teen with a buzzed scalp panted in the doorway. He wore a brown jean jacket and construction boots. The gray winter sky illuminated his smooth cheek.

“It’s going down! It’s going down over at Senn right now! Dey’re runnin’ dem niggers out de neighborhood!” he yelled.

Moments later, you briskly walked east down Bryn Mawr Ave. toward the Red Line “L” stop. Large clots of salt-blackened snow lined the edges of the sidewalk; the freezing weather preserved them, shin-high and sloped, like tiny mountain ranges. The teen knew not to talk to you. He knew he’d get no response. He was afraid to even look at your hawkish scowl and the broken and re-broken nose. They sent him to deliver the message and show you where. That was all.

This silent, negative charge radiated from you. You ground your teeth and stomped on in Chicago’s burning January freeze—a freeze that can paint a man’s face and hands red in seconds. A rumble of shouts and honking car horns built to the north. When you got to Wayne Ave., you peered down the narrow corridor of the one-way street, which intersected with Ridge Ave. at a forty-five degree angle. An immense, calamitous procession ambled slowly down Ridge. You quickened your pace to a jog and cut down Wayne. As you approached Ridge, you saw a long line of leather coat-clad city police officers with their powder-blue chests peeking out near their collars. The cops’d taken one of the southwest-bound lanes and surrounded a parade of over a hundred black teenagers. Traffic skirted slowly around them. An awestruck young mother eked past in a brown four-door Buick. Her young boys’ faces were glued to the window in back.

At first, you could only see the black boys’ faces, which were stoic and resolved. Their feet slipped on the thin films of ice. They were twisted at the waist with their arms locked elbow-in-elbow to create an intertwined shield of bodies. A black kid with a fuzzy gray skull cap and a black quarter-length pea coat bugged his eyes out at the faction of white hoodlums across the street who stalked them from across the way. They were just a few feet up the sidewalk from you. The black boy muttered, “Mothafuckas,” quietly.

Then, you saw the girls inside the arm chain. One thick-boned, dark-skinned girl pressed her school books tightly to her chest. Her full lips pursed. Her eyes darted from her snow boots across Ridge to the gang of white thugs that bellowed cat calls at her. All the white hoods were clad in tight jeans and tan construction boots. Their hair was either buzz-short or slicked back tightly to their scalps. One of them was a head taller than the rest. His hair was swirled back in a ducktail, and his dark-brown jean coat read “T.J.O.” in black, block-shaped letters high across the back. He had a jagged, angular face and wild eyes. His large Adam’s apple yo-yoed along his narrow throat as he cackled. You knew him as little Kellas. You’d kicked his ass a hundred times while he was growing up, and you got him hired on as a laborer at a high-rise job a few months back when he dropped out of school. He showed up until the first payday, cashed the check, and vanished. He was like another little brother to you.

Kellas craned his head back like a rooster. His scratchy voice careened over the others: “Come on, baby! Don’t be shy! Bring that big, nasty fanny on over an’ sit it down right here.” He yanked at the crotch of his black jeans, and the gang erupted into laughter. A smirk slithered across the lips of a young, pudgy copper in an ankle-length trench coat. The cop looked down. His polished black boots stomped atop the salt-faded, yellow dotted line while his maple billy club swung in circles from the strap around his wrist.

You followed behind this group of rambling roughnecks, keeping your distance. Your wide hands flexed and gesticulated with the burning sensation there in your palms that always appeared when you itched to give somebody a smack—the kind of slap that leaves the recipient snoring on the sidewalk. The teen ran up to Kellas and yanked at his coat sleeve, then pointed back at you. Kellas turned and grinned maniacally. He raised his palm towards the marching students. His eyebrows hiked upward. You grimaced and your face flushed red.

“Who’s dat?” someone asked.

“Dat’s the leader of Bryn Mawr,” Kellas replied.

You walked on—your jutting chin tucked into your throat. The procession reached the three-street intersection at Bryn Mawr, Broadway, and Ridge. The white gang halted at the sharp peninsula where Ridge and Bryn Mawr touch. There were fifty or more now. They spilt out into the streets. A short, stout guy with acne bubbled across his cheeks stumbled out into the street and puffed his chest out.

“WHAT’D MARTIN LUTHER KING EVER DO FOR ME?” he yelled, his vicious tone piercing the bedlam.

You walked up beside Kellas, but he didn’t turn. He kept his gaze on the mob of black and blue that encompassed the high-schoolers.

“You told me there was gonna be a fight,” you said, baring your teeth. “They look like they just want to go home.”

“And we’re seeing ’em off,” Kellas replied, smiling. Then, he cupped his hands around his mouth, leaned back, and rocked up on his tip-toes to yell, “GOOD RIDDENS, NIGGERS!” The wind whirled and frayed his greasy, dark-brown hair, and it wimpled up in thin strands like tentacles.

The procession stopped traffic in all directions. The honks of car horns rose in a steady, long, mournful chorus that encircled the procession in the melodic agony of the city. The police and students crossed Broadway—a slow, sad parade. They sifted up toward the Bryn Mawr “L” stop.

You watched them for a while. Thin trails of steam rose from their mouths and nostrils and accumulated and congealed into one misty haze above the procession. The hoods roared at your sides. Their laughter felt like pinpricks in your earlobes.

“Fuck this,” you spat. You turned away down Bryn Mawr and walked home.