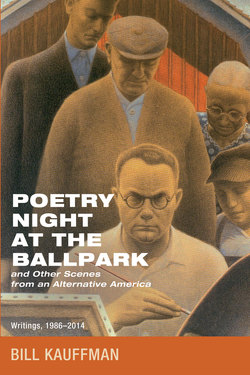

Читать книгу Poetry Night at the Ballpark and Other Scenes from an Alternative America - Bill Kauffman - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Bullish on Buffalo

ОглавлениеThe American Conservative, 2009

If it’s January the Buffalo Bills must be scattered to the greens of fifty golf courses, far from the howling winds and superabundant snows of their autumnal “home.” Only one Bill, backup linebacker Jon Corto, is native to the region. The remainder are about as Buffalonian as Caroline Kennedy.

The localist solution is a territorial draft, so that the Bills would be of Buffalo and not just mesomorphic mercenaries. Of course this would lead to an NFL based in California, Texas, and Florida, with western New York kicked into a minor league. That’s okay. Majors have cash but minors have soul.

Far removed from the glory days of four consecutive Super Bowl appearances in the early 1990s, the Bills’ only recent distinction came from the Sunday morning boostering of my old boss Tim Russert of South Buffalo. I remember Tim before he was a saint, when he was a hail-fellow political operative picking off Pat Moynihan’s hapless Republican would-be challengers with all the zest of a giddy teenager zapping aliens in a video game. I’ll bet ex-Bills QB Jack Kemp was more afraid of Russert than he ever was of Buck Buchanan.

While the Bills skidded to another sub-.500 record this season, I contented myself with Larry Felser’s The Birth of the New NFL: How the 1966 NFL/AFL Merger Transformed Pro Football (Lyons Press). Felser was present at the creation, covering the formation of the American Football League in 1960 for the Buffalo Courier-Express, though I suppose his greatest distinction came in marrying Beverly, who defeated my mother in the Elba Onion Queen pageant of 1957. I don’t know if mom has forgiven her yet.

Those beautiful old AFL names—Houston Antwine, Gloster Richardson, Cookie Gilchrist—evoke the dawn of my football consciousness in that antediluvian age of the tie game, the straight-ahead kicker, and the white cornerback. Felser was there and he took notes. The AFL was a spirited underdog but it was no pastoral dream: the San Diego, nee Los Angeles, Chargers were named after owner Barron Hilton’s hotel chain’s credit-card operation. What a loathsome derivation!

But consider Felser’s take on the cartoonish villain Al Davis, owner of the Oakland Raiders. Davis, as commissioner of the AFL, hired ex-Buffalo Evening News sportswriter Jack Horrigan as his PR man. When Horrigan was diagnosed with leukemia, writes Felser, “Davis, a Jew, bought a votive candle in a Catholic religious supply store. Back in his office, he lit the candle as a devotion, a prayer in flame—a Catholic custom. When the office was about to close that evening, a cleaning lady informed him it was against building policy to leave a burning candle unattended. Davis took off his coat and stayed the night.”

That doesn’t make up for yanking the team out of Oakland for thirteen years, but Al can’t be all bad.

Pro football today is nigh unwatchable due to the chronic TV timeouts which interrupt the flow of the game and remind the assembled just who is boss. After scores or changes of possession the twenty-two behemoths on the field wait meekly for a spindly TV semaphorist to give the referees the signal to resume play. What would happen if the players defied the Great God Television and just started playing? There would be consequences, I imagine.

Mauling women, popping loudmouths in bars, shooting steroids: these things the mansters of the gridiron will do, but disobey television—never.

The major-college game is just as compromised, though the exigencies of recruiting give most teams a regional accent. My football preferences are outré: I am a Catholic peacenik whose favorite teams were Brigham Young and Army before the University of Buffalo Bulls staggered into Division I in 1999. UB had the worst program in college football until Turner Gill, a devout Christian gentleman and miracle worker, came to town three years ago. Gill vitalized the team with local products James Starks of Niagara Falls and Buffalo’s own Naaman Roosevelt, so that the Bulls of Buffalo are, in some sense, representative of Buffalo. This year UB played in a postseason game for the first time ever—the unfortunately named International Bowl in Toronto.

Bulls fans expected a bittersweet end: Gill would leave town at season’s conclusion, lured by a fat contract from a football factory. No one—well, almost no one—would have blamed him. In America, people are expected to move for money. Loyalty is penury. Immobility is for suckers and losers.

But Turner Gill is staying. Passed over for the Auburn job—reportedly for the stupid racist reason that the coach, who is black, has a white wife—Gill is casting down his bucket where he is, at least for now.

Stay is such an underrated word.