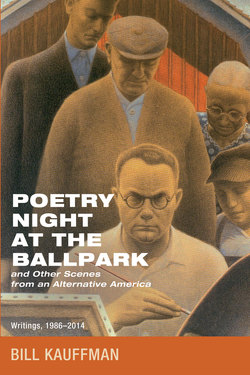

Читать книгу Poetry Night at the Ballpark and Other Scenes from an Alternative America - Bill Kauffman - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Peace in River City

ОглавлениеThe American Conservative, 2011

Our daughter will be spending the snowy months rehearsing her role as Marian the Librarian in her high school’s production of Meredith Willson’s The Music Man, that tuneful Iowa-placed warhorse—no, parade horse—of community theater. (The flaw in community theater is that while the actors are drawn from the community, the playwrights seldom are.)

It’s been an autumn of imposture, as my wife played the lead in a sharply observed one-act, “Blind Date,” by the late great Horton Foote of Wharton, Texas, whom a friend calls “the last straight man in American theater,” by which she does not mean that he set up punch-lines for comics. The Internet, I learned, is not wholly useless: Lucine created her accent by watching Lady Bird Johnson clips on youtube. You remember Lady Bird: the cuckquean who had the gall to scold Americans about the ugliness of highway billboards while her grotesque husband was ordering the murder of hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese and Americans in Southeast Asia. There are degrees of ugliness, Bird.

In 1966, LBJ appointed Meredith Willson to the National Council on the Humanities, but hey, everybody’s imperfect. And that was the last time Mason City, Iowa, would ever have a voice in government-subsidized culture. Although Meredith had long since lit out for Southern California, the notes in his head were always Iowan. He was said to have been the largest baby (fourteen pounds, six ounces) born in Iowa, which perhaps justified that superfluous L in his surname. Meredith Willson’s father, an attorney, had played baseball at Notre Dame, where he was taught to throw a curveball by the inventor of that pitch, Candy Cummings. Meredith’s sister, Dixie, a literate Ziegfield Follies chorine and silent-movie screenwriter, wrote the oft-anthologized poem that begins “I like the fall/The mist and all.”

So the Willsons were one of those families of talented eccentrics, some grounded and some not, who grow like beautiful weeds whenever small-town America is left alone to develop in its own way, in its own time.

Mason City also gave us Hanford MacNider, national commander of the American Legion in the 1920s and a believer in “Iowa as the Promised Land.” The Legion once was a potent lobbyist for loot, though veterans’ benefits were meager recompense to those who came home legless or armless or blind or insane from the single-L Wilson’s War to End All Wars. MacNider, a banker, introduced the most un-Mr. Potterish “Iowa idea,” which required each Legion post to “make some unselfish contribution to its community’s welfare each year or lose its charter.” I’d say ninety years of sponsoring American Legion baseball teams is a pretty fair contribution.

Peace has long been an Iowa idea as well. Hanford MacNider was given to such craven and anti-American utterances as “I am . . . unwilling to commit my sons or any American’s sons to the policing of the rest of the world.” Traitor! MacNider played football at Harvard and earned a chestful of medals in both world wars, but he had an Iowa isolationist streak that such he-men as Lindsey Graham and Rick Santorum would find suspiciously girlish.

Iowa isolationism was also embodied, in rather different bodies, by the New Left historian William Appleman Williams of Atlantic, Iowa, and by Barry Goldwater-Eugene McCarthy supporter Donna Reed of Nishnabotna, Iowa. (I’ll bet Donna could have thrown a mean curveball, too; watch her fling that rock through the upper window of the old Granville house in It’s a Wonderful Life.)

I devoted a chapter to Iowa’s prewar culture—Grant Wood, Jay Sigmund, Ruth Suckow, Marvin Cone—in my book Look Homeward, America (2006). Its artistically fecund soil was so much richer than barren Manhattan. And it produced worthy political leaders, too, from the cantankerous Old Right skinflint H.R. Gross to the radical farm crusader Milo Reno.

Meredith Willson seems to have been fairly apolitical, though he did, mind-bogglingly, compose a march commissioned by President Ford for that phlegmatic Michigander’s Whip Inflation Now (WIN) campaign. That combination is so far beyond unhip as to propel the WIN March into its own dimension of occult stodginess. Maybe the University of Michigan marching band can thump it out next time the Wolverines play the Iowa Hawkeyes?

I hear tell that there are caucuses, if not crocuses, coming up in Iowa. As far as I know, only two men in the mix—Ron Paul and Gary Johnson—come anywhere near the Iowa Idea. Not that politics is the answer. If the Mason Cities of our country are ever to reflower, they need peace and poetry and music—the mist and all.