Читать книгу The Rock Island Line - Bill Marvel - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ОглавлениеI grew up amid railroads. Great-grandpa Marvel finished out his career as a Colorado & Southern conductor five years before I was born. Burlington’s 38th Street Yard was just a vacant lot from my grandparents’ back porch. Union Pacific’s Denver–Cheyenne trains hustled past my great-aunt’s house in suburban Henderson. Rio Grande’s big 3600-class “malleys” were a constant presence on family fishing trips and vacations. When we moved from West to East Denver, the sound of slamming boxcars in Rio Grande’s Burnham yards was exchanged for the nightly departure of UP’s Kansas Division mixed. Through my open bedroom window I could always tell whether a steamer or a diesel was in charge.

But the Rock Island was an exotic stranger. It rolled into town from across the High Plains, from places I could only guess at. My first encounter came while I was watching a softball game with my father. A rumble arose from behind the grandstands and I turned just in time to see one of Rock’s magnificent red and maroon TAs trundle by from the Burnham roundhouse, on its way to Union Station to take the Rocket east.

I never forgot that apparition. So naturally, when I turned my attention to railroads in a serious way, the Rock Island was a favorite. Other fans hung out at the C&S, which was still switching Rice Yard with steam, or headed down to the Joint Line for the parade of C&S and Santa Fe freights and the daily passage of Missouri Pacific’s Eagle. I was as likely to point the hood of my battered ’49 Ford east, to Sandown or Sable or Strasburg, where, if I was lucky, Rock Island FTs or FAs, or even an exotic BL2 would be on the move. What a great way to run a railroad, I thought, never realizing that it was because of poverty that Rock was still running first-generation power when every other road in town had moved on to GP20s and -30s.

The cab window is open and the weather is balmy on this fine April morning in 1965 as a rush-hour commuter run heads for La Salle Street behind BL2 No. 429. The BL stands for “Branch Line,” obviously not the service in which it now finds employment. Marty Bernard

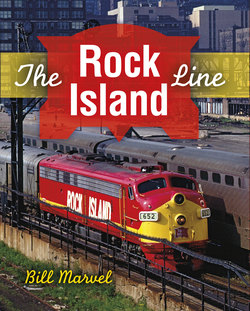

Some liked it, some loathed it, but the railfan-designed bicentennial paint scheme for E8A No. 652, the Independence, looked better than the patriotic costumes that adorned most other roads’ diesels in 1976. The year after the whoopla, the unit oozes steam on a frigid February morning as it makes a quick station stop at Joliet. Dan Tracy

This book, in a way, is the story of that poverty and how and why it came about.

To help tell the story I leaned on the work of more than a dozen photographers, some of them shooting buddies, others known only by reputation and the quality of their work. All came through gloriously, as these images show. The bylines will identify them, but I owe special thanks to Ron Hill, Dale Jacobson, and Paul Dolkos, with whom I have had the pleasure of sharing happy days at trackside. Ed Seay Jr. and Lloyd Keyser dug into their personal collections. The others whose work is displayed on these pages went to great lengths to provide the images I asked for, entrusting me with irreplaceable slides. Many went to the trouble of scanning images and sending me discs. Thanks, gentlemen—this is as much your book as mine.

Eunice J. Schlichting, chief curator at the Putnam Museum in Davenport, Iowa, and Coi Gehrig at the Denver Public Library Western History Collection smoothed the way to those important collections. The DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University provided a refuge, a reading room, and access to one of the best railroad libraries in the country. Victor F. Kralisz, manager, Humanities and Fine Arts Divisions of the Dallas Public Library, made precious writing space available in that library’s writer’s room when my dining room table overflowed.