Читать книгу The World of Sicilian Wine - Bill Nesto - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

PERPETUAL WINE

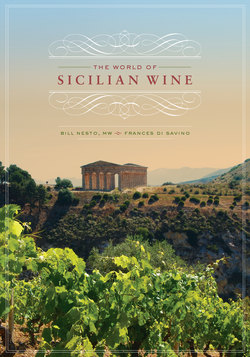

About ten years ago, Giacomo Ansaldi bought and restored the nineteenth-century Baglio dei Florio, on a rocky plain that overlooks the vineyards of the contradas Birgi and Spagnola, the Stagnone saltworks and nature reserve, the island of Mozia, the Egadi Islands, Erice, and Marsala. Baglio is an Italian word for a rectangular building enclosing a central courtyard. The Florio family had built this structure amid their vineyards to house equipment, employees, and, during the height of the harvest, the family itself. To avoid trademark infringement with today’s Florio Marsala wine company, also no longer owned by the namesake family, Ansaldi renamed the building Baglio Donna Franca, after Franca Florio, the vivacious and stylish wife of Ignazio Florio III. Today Donna Franca comprises both a hotel-restaurant and Ansaldi’s boutique winery, La Divina.

On our visit to La Divina, we tasted wines out of barrel with Giacomo in the basement cellar. We faced a lineup of eight large oak barrels supporting a layer of seven on top. An impish smile spread over Giacomo’s face. He tossed me a piece of chalk. “Taste them and write your notes on the barrels. You are the master. I’ll be back in fifteen minutes.”

He climbed the spiral staircase that ascended into the winery. A door opened. Voices and the clang of metal against metal flowed down like water into the cool, still air of the cellar. This being early September, the harvest was in progress. The tanks in the winery were filled with “boiling” musts, turbulent, bubbling grape juice at the most active point in fermentation. There was much for Giacomo to do. He closed the door behind him with a decisive thud. Silence. We were alone in his nursery of perpetual wines.

Vino perpetuo means “perpetual wine.” It is perpetual because its high alcohol content, 16 to 18 percent, makes it stable and because whatever is consumed is replenished with younger wine. Hence it goes on forever. Just as cheese is a way of preserving milk, vino perpetuo is a method of preserving wine. Its existence as a wine type probably goes back further than historical records can take us.

Small farmer families near the western coastline of Sicily still maintain vino perpetuo a casa (“at home”). Its flavor is unique, serendipitous, and essentially familiar because it results from where and how it is kept. The decisions of generations of individual family members become embedded in the wine. Overmature Grillo grapes are the preferred materia prima because this native variety is the most likely to yield wine with the presence and body to endure extended aging. When harvested late, Grillo grapes have higher sugar levels than other Marsala grapes. The result is higher alcohol in the wine.

Though each vino perpetuo is unique, their exposure to oxygen through barrel staves and bungholes causes reactions that lead to similarities in color, smell, and taste. Each is amber in color and powerfully nutty and airplane-gluey (the latter from ethyl acetate) in smell. Sicily’s dry climate causes water to evaporate faster than alcohol. As a result, the wine’s alcohol percentage rises above 16 percent, which adds a fiery, “hot” taste. Grillo grape skins and pulp contain unusually high potassium levels. Normally potassium means a wine is less acidic in taste, but most of Grillo’s acidity remains fixed. The resulting potassium salts may account for a subliminal perception of salt. Mediterranean Sea spray landing on the grapes—which are not washed before vinification—enhances that salinity.

Earlier in the day, Giacomo had brought us to the shoreline several miles north of the port of Marsala. “Qui nasce il perpetuo” (“Here is born the perpetual wine”), he proclaimed as he braked his silver Mercedes wagon. He pointed over his left shoulder at the other side of the road, where there was a sprawling vineyard with low green-leafed vine bushes scattered higgledy-piggledy in black soil. Giacomo next pointed to our right. “Over there is the Stagnone Lagoon and the island of Mozia.” Alongside the lagoon were mounds of shining white crystals covered by red roofing tiles. “That is sea salt, the best in Sicily.” Then there was the lagoon. Lines of rocks crisscrossed it, creating a checkerboard of muted shades of blue, green, and violet. He explained that the sun and the wind caused the water to evaporate rapidly in the shallow square pools, concentrating the seawater until a salt residue was all that was left. Workers collected the salt, piled it on the mounds, and protected it from wind and rain with the roofing tiles. Windmills punctuated the scene, their bony sails pinwheeling in the steady breeze. In the Marsala area, winds blow three hundred days a year. The mills grind the salt before it is sold. Across the lagoon was Mozia, a low-lying island of green with a few buildings visible. Beyond that was the Mediterranean Sea.

Giacomo pointed to the island. “The Phoenicians, then the Carthaginians had an important trading settlement there from 700 to 400 B.C. The whole island is covered with ruins of buildings. In a museum on the island, you can see clay jars that must have once contained wine. Vases and cups showing images of grapes and people drinking wine show that they enjoyed wine. More than likely, the inhabitants grew grapes along the coastline, probably in this field right here.” He waved his hand at the vineyard on the other side of the road.

Looking up as if he could see something in the sky, he said, “My dream is that my vino perpetuo will be born here. I want to buy this vineyard. The vines, nearly all Grillo, are very old, some nearly one hundred years old. I will make the wine, then barrel it. As it becomes old, I will bottle some and then replace what I draw out with young wine from this same vineyard.”

At first glance it was hard to believe the vines were that old, because they looked like small leafy bushes, or alberelli. “Look at this one!” He raised a mound of leaves to show us the ankles of a small tree. “Questo è vecchissimo!” (“This one is very old!”) He then pointed to a low-lying, sprawling vine bush with wide, shiny round leaves. “That is Riparia, an American vine, planted long ago as a base for the Grillo. The top of the plant, the vinifera part, has died. All these vines have American roots. Rootstocks like this one are no longer available through commercial sources like nurseries. These were introduced in the late 1800s. Because of their age, the roots of these vines reach down deep into the soil, deep into the past.”

Giacomo yanked a bunch of ripe golden grapes off the vecchissimo. He pressed one between his thumb and forefinger, looked at it and smelled it, then showed us. “The skins are thick but disintegrate easily. The grape is ripe. The citrusy, musky smell is intense. The skins are loaded with aromatic precursors.” He chewed the brownish grape seeds. He looked up smiling. His eyeballs danced. “Croccanti! [They are crunchy!] Like nuts. Perfect!”

“An old man owns this vineyard. After years of my asking him if I could buy his fruit, he has finally said yes. One day I hope to buy this vineyard from him. I can’t tell him that, because if he knows I want it, he will raise his price.” We zigzagged through the alberelli, making our way back to the car. A sign indicated that an adjacent vineyard was for sale. Giacomo took out his cell phone and dialed the seller’s telephone number. He turned his back and lowered his head, spoke into the phone, then snapped it shut. “I left the owner a message telling him that I was inquiring about the vineyard for sale. I can bargain better because I want it less. He will sense this, so he will sell it to me cheap. Once I buy it, I will, by Italian law, have the option to buy the one I really want as soon as it comes up for sale. In Sicily you must be patient and work in ways that are not obvious.” We got back in the car and made our way east, inland.

When John Woodhouse first arrived in Marsala, in 1770, he sampled a local wine referred to as vino perpetuo. A wine connoisseur, he noted its similarities to Madeira, a fortified wine prized by the English market. He realized that he could fortify the local wine and make a wine similar to vino perpetuo. He could then sell this in the British market at a competitive price. The Marsala wine industry was born.

“Old maps show that along the coast here north of the port of Marsala was where the vineyards were when Woodhouse first arrived in Marsala,” Giacomo told us. As we drove inland, the land gradually rose. Pitted white-gray stones appeared more frequently. About a mile inland, the incline increased. Giacomo pointed out that we were moving from the littoral plain, where the soil was black and rich, up and over a limestone plateau. Vineyard expansion occurred here during the early nineteenth century. I could see that the soil varied from deep red to light brown. Giacomo told us that the red was from iron leached from the limestone by thousands of years of rain. (The rains come during the winter.) We drove along this plateau, which gave us a panorama of the sea. The vegetation was scrawny. Vineyards alternated with spaces littered with chalky rocks of all shapes and sizes. At some points in the journey, it looked like we were on the surface of the moon.

Our guide spoke as he drove: “Woodhouse’s success attracted others, first fellow Englishmen in the early 1800s, then, by the mid-1800s, Sicilians.” We stopped in front of a stone archway rising up among rocks and weeds. Behind the archway were the ruins of a large stone house. Where the roof should have been there was blue sky. We stood on a rock wall to get a better view. Through one window we could look through another to the shimmering Mediterranean. The smell of burned vegetation filled the air. Farmers were burning brush. The weeds in front of the wall grasped clear plastic bottles and white plastic shopping bags. A mangy dog sauntered like a ghost through the ruins.

“This is one of Woodhouse’s baglios,” Giacomo announced as we peered in. “Marsala families built these stone houses. Woodhouse and the other large producers set up many baglios in the vicinity of their grape sources, as well as one large one at the port of Marsala. This one is in contrada Mafi. Look how this baglio commands a view of the plain below and the Mediterranean Sea. Most baglios were strategically positioned. Sicily has always been invaded from the sea. Baglios were sentinels as well as places to live and work.” Later we found out that as many as twenty-seven people owned a part of this ruin. One might own half a wall, half a stairway, half an arch. In order for this baglio to be restored, all twenty-seven would have to agree to sell. Everyone waits for others to sell first. They believe that they can get a higher price as the buyer becomes more desperate to own the final plots. So nothing happens. Not having this historic property and others like it sensitively restored cuts the nose off Sicily, disfiguring its face. Giacomo, however, feels the magic and the potential of this baglio. “I would love to buy this place. I would love to bring it back to life.”

We went back to the car and drove to the northern edge of the limestone plateau, which looks over a vast plain carpeted with patches of vineyards. In the distance loomed Erice, a well-preserved medieval town atop a mountain. Erice Mountain rose like a huge sperm whale out of a green sea. We could see the profiles of the buildings of the town bristling like tiny teeth on the summit. On many days, when the sun pours down on Trapani, Erice’s closest port, just to its east, the town of Erice is veiled in clouds. The province of Trapani has more acres planted to vines than any other province in Italy. It accounts for more than 55 percent of the vineyards planted in Sicily. Just visible to the east were the hills of Salemi, where the higher altitudes and distance from the sea make lower-alcohol wines with less tactile structure. The grapes grown in Salemi are better suited for modern white wine sold by the bottle than for base wines for Marsala. South of Marsala is Mazara del Vallo, where growing conditions are similar to those near Marsala.

Giacomo pointed out, though, that the soil of the plains between us and Erice consisted of heavy clay, better suited to growing cereal than vines. Innumerable local families owned tiny plots. Most owners had other jobs that supported them. They farmed these vineyards to supplement their incomes and to retain their families’ historic connection to agriculture.

Giacomo showed us a vineyard his family owns. As a child, he loved working with his father in the family vineyards. This particular plot had an added attraction. A shepherd had bivouacked his sheep within the walls of an eviscerated nineteenth-century baglio just down the road. Every morning he made fresh ricotta. The warm ricotta was young Giacomo’s early morning treat.

He walked over to the ruins of that baglio. Another shepherd now presided. Giacomo went up and joked with him in the local Sicilian dialect. He wanted to assure the man that we were not there to make his life difficult. The shepherd was a squatter. We walked past a shed surrounded by a litter of cats and several scruffy dogs. Opposite the shed, an imposing stone arch allowed entry into the courtyard. As was the case with Woodhouse’s baglio, there was no sign of a roof. Stones had been pulled from the walls to barricade windows and doorways so as to confine the sheep to the courtyard. Clumps of wool stuck in crevices. An overturned cast-iron bathtub had been their feeding trough. We walked up to a stone well in the center of the courtyard. An apron of rounded stones spread out and was then buried in the sea of black sheep feces that covered the courtyard. I tried to imagine the smell of the fresh, warm ricotta that young Giacomo had savored decades earlier.

“This is a baglio, Baglio Musciuleo, once owned by Ingham,” he said. Benjamin Ingham founded his Marsala company in 1812. While Woodhouse modified the local wines, Ingham improved the base wines by systematizing viticulture. In time, his company became larger than that of Woodhouse. A handful of English entrepreneurs, most notably John Hopps and Joseph Gill, also came to Marsala to produce their own Marsala wine. It is ironic but telling that Sicily’s most famous historic wine was the invention of foreigners. It is also telling that the first Sicilian producer of Marsala, Vincenzo Florio, was not originally from Sicily but Calabria. For Giacomo, as for Sicily, the age of Woodhouse, Ingham, and Florio was pivotal.

Giacomo’s final stop was Baglio Donna Franca. Across the street from Baglio Woodhouse, the Florios had built this much larger baglio. Phalanxes of vines on our right loaded with purple Nero d’Avola grapes marched across brownish white soil. On our left, behind a low rock wall, vines carrying golden-yellow bunches of Grillo paraded across brilliant red soil. In front of us the large dimensions of Baglio Donna Franca signaled the heyday of the Marsala wine industry. The massive high white wall was almost blinding in the sun. Midway along its breadth was an arched entry to a central courtyard. Giacomo looked up and pointed at a squat structure above and to the side of the archway. “That is an old Saracen tower. It dates back to the eleventh century. From that high point the Saracens looked out across the sea, searching for the ships of their enemies.”

Giacomo sighed, his mind revisiting the moment a decade ago when he had strolled through the ruins of what came to be called Sceccu d’Oru (“The Golden Ass”) after World War I. During the war, the Florio family had set up a clandestine distillation operation in the baglio. This was to avoid the taxes the government set on spirits that Marsala producers had to buy to fortify their wines. Ass was the code name for a still in the local language. The spirits that came out of it were as valuable as gold. “You should have seen this place when I bought it. It looked as bad as what we saw at Woodhouse’s and Ingham’s baglios.” We entered the central courtyard. Several large palm trees provided shade. Circling the courtyard were buildings constructed at intervals along the surrounding walls. A larger-than-life artistic rendering of Franca Florio gazed dreamily from an elevated perch. She flaunted a string of pearls that dangled down to her knees. This fashion diva reigned supreme, as if she had never left. Just as the Florios’ entrepreneurial bent had irritated Sicilian blue bloods, Franca Florio’s interest in fashion, culture, and politics went beyond what was considered ladylike for well-bred Sicilian women of her day.