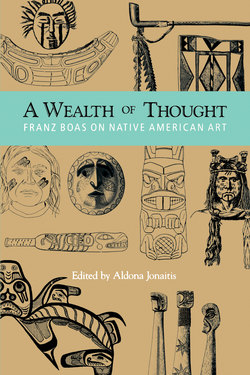

Читать книгу A Wealth of Thought - Boas Franz - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2. The Use of Masks and Head Ornaments on the Northwest Coast of America

Boas first briefly discusses the difficulty of obtaining information on the meaning of Northwest Coast art. Then he categorizes three types of masks: the helmets found in the north (among the Tlingit), masks attached to housefronts and totem poles, and dancing masks. Two classes of dancing masks of the Bella Coola and the Kwakiutl are those worn at potlatches and those worn during the winter ceremonials. The remainder of the essay is a description of the winter ceremonies of the Kwakiutl with references to some of the paraphernalia worn by participants.

This essay represents a preview of Boas’s 1897 “Social Organization and the Secret Societies of the Kwakiutl Indians” and his 1898 “Mythology of the Bella Coola Indians.” In those later publications, he used somewhat different linguistic notations from those he uses here.

Our museums contain large collections of masks from the Northwest Coast of America, but it is only occasionally that the descriptions and catalogues give information as to their use and meaning. On my first visit to British Columbia, in 1886, I paid special attention to this subject. A considerable collection of drawings and photographs of masks, which I carried with me, did not help me materially in my investigations. I frequently showed the drawings to Indians whom I expected to be conversant with everything referring to this subject, but it was only in rare cases that they recognized the masks and were able to give any information as to their use and meaning. Very soon I arrived at the conclusion that, except in a few instances, the masks were no conventional types representing certain ideas known to the whole people, but were either inventions of the individuals who used them, or that the knowledge of their meaning was confined to a limited number of persons. The former hypothesis did not seem probable, as the same types of masks are found in numerous specimens and in collections made at different times and by different persons. Among the types which are comparatively frequently found, I mention the Tsonō’k˙oa1 of the Kwakiutl, … the crane, eagle, and raven.

Further inquiries showed that the probability of ascertaining the meaning of a mask increased when the particular village was visited in which the specimen was collected. It was thus that I ascertained the meaning of the double mask figured in Woldt’s “Cpt. Jacobsen’s Reise an der Nordwestküste Amerikas” [Jacobsen 1884:129]. The outer face represents a deer; the inner, a human face. It refers to the tradition of the origin of the deer, which originally was a man, but was transformed, on account of his intention to kill the son of the deity, into its present shape. At last I found that the use of masks is closely connected with two institutions of these tribes—with their clans or gentes, and with their secret societies. The latter class of masks is confined to the Kwakiutl, Nutka, and Tsimshian, and I believe that they originated with the first-named people. The meaning of each mask is not known outside the gens or society to which it belongs. [Boas uses “gens” or “clan” here for what he later calls “numaym” (see Suttles 1991).]

This fact makes the study one of great difficulty. It is only by chance that a specimen belonging to one of our collections can be identified, as only in rare exceptions the place where it was purchased is clearly stated. The majority of specimens are purchased in Victoria, where they are collected by traders, who, of course, keep no record of their origin.

Besides this, the Indians are in the habit of trading masks, and copying certain models which strike their fancy from neighboring tribes. The meaning of these specimens is, of course, not known to the people who use it, and it is necessary to study first the source from which such carvings were derived. Thus the beautiful raven rattles of the Tsimshian are frequently imitated by the Kwakiutl, and the beautifully woven Chilcat blankets are used as far south as Comox. The carved headdresses of the Tsimshian, the Amhalai’t (used in dances), with their attachment of ermine skins, are even used by the natives of Victoria.

My inquiries cover the whole coast of British Columbia. In the extreme northern part of this region a peculiar kind of mask, which has been so well described by Krause [1885], is used as a helmet. I do not think that this custom extends very far south. Setting this aside, we may distinguish two kinds of masks: dancing masks and masks attached to housefronts and heraldic columns.

The latter are especially used by tribes of Kwakiutl lineage and by the Bilqula [Bella Coola]. All masks of this kind are clan masks, having reference to the crest of the house owner or post owner. They are generally made of cedarwood and from three to five feet high. One of the most beautiful specimens I have seen is a mask of the sun, forming the top of an heraldic column in Alert Bay, Vancouver Island. It belongs to the chief of the gens Sī’sentlē of the Nimkish tribe. The latter is the second in rank among the tribes of the Kwakiutl group, which form one of the subdivisions of the linguistic stock of the same name. The clan claims to be descended from the sun, who assumed the shape of a bird, and came down from heaven. He was transformed into a man, and settled in the territory of the Nimkish tribe. The name of this mask is Tlēselak• umtl (sun mask, from tlē’sela, sun; ik• umtl, mask). It has a bird’s face, and is surrounded by rays. Certain clans of the Bilqula have the mythical Masmasalā’niq, covered by an immense hat, on the tops of their house-fronts; but the use of masks for this purpose is, on the whole, not very extensive.

In order to understand their meaning and use, it is necessary to investigate very thoroughly the social organization of each tribe, and to study these masks in connection with the carvings represented on the posts and beams of the houses and with the paintings found on the housefronts. Thus the Kwakiutl proper are the highest in rank among the group to which the Nimkish belong. They are divided into four groups, which rank as follows: first, the Kue’tela; next the K˙’o’moyue or Kue’qa (the latter being their war name); then the Lo’kuilila; and finally the Walaskwakiutl. Each of these is divided into a number of clans, some of which, however, belong to two or three of these divisions. I shall mention here the divisions of the Kue’tela only, again arranged according to rank, and shall add their principal carvings.

1. The noblest clan is that of Matakila. Their chief wears a mask representing the gull, and they use also masks of animals representing the food of the gull. Their beams are not carved.

2. Kwokwa’k˙um. The posts supporting the beams of the house represent the grizzly bear, on top of which a crane is sitting. Their mask represents the crane.

3. Gye’qsem. Their post represents a crane standing on a man’s head.

4. La’alaqs’end’aio, who are the servants of the Kwokwa’k˙um. Their post is a killer (Delphinus orca) with a man’s body.

5. Si’sintlē (the same clan as that of the Nimkish). Their carving is the sun. Besides this, they use a dog’s mask, representing the dog which accompanied the sun when he was transformed into a man, the Tsonō’k˙oa, and several other carvings.

Each clan has a number of secondary carvings which have reference to the traditions relating the adventures of its ancestor.

As will be seen from this list, the emblems are also used as dancing masks. The use of masks for this purpose is spread all over the coast, being found among the Tlingit as well as among the tribes near Victoria; but among the latter very few types of masks are used, and it is the privilege of certain tribes and clans to wear them.… a number of these masks are illustrated. Before discussing their meaning, I have to say a few words as to the use of dancing masks.

We may distinguish two classes of dancing masks—those peculiar to the several clans and those belonging to secret societies.

The former are of two different kinds—masks used at the potlatch (the festival at which property is given away), and masks used for the mimical performances in winter, when dances representing the traditions of the clans are acted. Masks must not be used in summer and during daylight, except the potlatch masks. The latter are worn by chiefs in the dance opening this festival. After the guests have arrived, the chief who gives the festival opens the ceremonies by a long dance, in which he wears the principal mask of his gens. Thus the chief of the gens Sī’sintlē of the Kwakiutl uses the sun or the Tsonō’k˙oa.… Other masks of this kind represent the ancestor of the clan. Thus I found a mask representing Nomas (= the old one [fig. 1]), the brother of the raven, used by the chief of a clan of the Tlauitsis, of which he is the ancestor. A few gentes do not always use masks at such occasions, but have large posts representing the ancestor, which are hollowed out from behind. The mouth of such a post forms a speaking tube, through which the chief addresses the assembly, thus acting the part of his ancestor.

By far the most interesting masks are those used in the winter dances. The Kwakiutl and all the neighboring tribes which belong to the same ethnological group have two different kinds of winter dances—one called Yā’wiqa by the Kwakiutl, Nō’ntlem by the Tlatlasik˙oala, Tlōola’qa by the Wik’ē’nok, and Sisau’kh by the Bilqula; the other called Tsā’ek˙a, Tsē’tsa’ek˙a, or Tlōk˙oa’la, and Kū’siut by the same separate tribes. The former dance takes place during the month of November among the southern tribes, early in October among the Bilqula. The latter is danced from December to February by the Kwakiutl, and from November to January by the Bilqula.

The masks [illustrated] are used in the dance Sisau’kh of the Bilqula. Figs. 2 and 3 represent the mythical K˙ōmō’k˙oa and his wife. K˙ōmō’k˙oa is a sea monster, the father and master of the seals, who takes those who have capsized in their canoes to the bottom of the sea. This being plays a very important part in the legends of many clans, marrying a daughter of the ancestor, or lending him his powerful help. I believe these legends originally belonged to the Kwakiutl, and have been borrowed by the Bilqula. The name K˙ōmō’k˙oa is undoubtedly of Kwakiutl origin; it has also been borrowed by the Çatlō’ltq [Comox tribe], the southern neighbors of the Kwakiutl. The masks are used in several mimical performances.

Figs. 4 and 5 belong together. They belong to a clan in whose history K˙ōmō’k˙oa plays an important part. K˙ōmō’k˙oa had married a girl, and the adventures of their son are acted in the dance. The young man (Fig. 4) calls the eagle (Fig. 5) and asks him to carry him all over the world. The eagle complies with his requests, and on returning the young man tells his experiences, how he had visited all countries and peoples and found them not to be real men, but half human, half animal. This latter idea is widely spread among the inhabitants of the Northwest Coast.

The next figure (6) is the mythical Masmasalā’niq.… The special mask represented here is used in a dance in which Masmasalā’niq appears in his house, at the entrance of which stands his messenger, Atlqulā’tenum, who calls, and announces the arrival of the various dancers, the Thunderbird, the Snēnē’ik˙ (the Tsōnōk˙’oa of the Bilqula), and others. Unfortunately I was unable to obtain this mask. It represents a human face, covered with parallel stripes which run from the upper left side to the lower right side of the face, and are alternately red and blue. He carries a baton painted in the same way.

FIG. 1. Kwakiutl mask representing brother of the raven

FIG. 2. Bella Coola mask of sea monster

FIG. 3. Bella Coola mask of wife of sea monster

FIG. 4. Bella Coola mask of young man

Fig. 7 is probably not used in the Sisau’kh, but belongs to the potlatch. It is a head ornament in the shape of the killer (Delphinus orca). Only the head, the tail, and the fins are represented. I was told that the idea of the headdress is to represent this whale as a canoe, the red horns being the paddles. Although this idea corresponds to some extent to the myths of the neighboring tribes, I doubt the correctness of this explanation. The horns, it will be seen, form a crown similar to the crowns of copper horns and mountain-goat horns used by the Tsimshian and Haida; and I believe our specimen is an imitation of the latter.

FIG. 5. Bella Coola mask of eagle

FIG. 6. Bella Coola mask of mythic being

FIG. 7. Bella Coola headdress in shape of killer whale

Although the last three figures are rather poor specimens of carving and painting, they nevertheless command considerable interest. The round mask (Fig. 8) represents the spirit Anulikū’ts’ai, and is used in the dance opening the Sisau’kh. Three spirits—Atlmoktoai’ts, Nōnōsēkne’n, and Anulikū’ts’ai—are said to live in the woods. Through their help men acquire the art of dancing, and whosoever wishes to become a good dancer invokes Atlmoktoai’ts to help him. It is said that they live in a subterranean lodge dug out by Nonosekne’n. From February until October they stay in this house, but then they leave it and approach the villages. As soon as they, and more especially Anulikū’ts’ai, appear, the dance Sisau’kh begins. Their appearance is the subject of the first mimical performance of the dancing season. A man wearing his mask waits outside the houses, and asks everybody whom he encounters why he does not dance, and through his presence instigates him to dress up and make his appearance at the great dance which is celebrated at night.

Fig. 9 represents the half moon. The mask is used in a dance together with the new and full moons. The mask is worn by a woman, and the being she represents is named Aiahilako.

FIG. 8. Bella Coola spirit mask

FIG. 9. Bella Coola half-moon mask

FIG. 10. Bella Coola mask in shape of a copper

Fig. 10 has the shape of the well-known copper plates which are so highly valued on the Northwest Coast. Its name is Tlā’lia (copper plate). The legend to which this mask refers says that a man went into a distant country to search for a wife. At last he met Tlā’lia, the mistress of the copper plates. He married her, and it was thus that they first came to be known to the Bilqula.

I said above that this dance of the Bilqula corresponds to the Nō’ntlem of the Tlatlasik’ oala. The double mask figured on page 129 of Woldt’s book [Jacobsen 1884] belongs to this dance. In the village Qumta’spē, which is commonly called and spelled Newetti by English traders, I collected a whole set of such masks, representing the “feast of the raven.” This collection has been deposited in the Royal Ethnological Museum at Berlin. The central figure is the raven, to whose face two movable wings are attached. The other figures represent animals which took part in the feast. The first part of the dance represents the raven catching the salmon, which is later on fried. The animals are invited to partake in the meal, and the events of this feast are represented in the dance. It was on that occasion that they received their present form, while before they had been half-human beings.

At the end of the Nō’ntlem season the Tsa’eka begins. During this season the whole tribe is divided into a number of groups, which form secret societies. Among the Kwakiutl I observed seven groups, the principal of which is called the Me’emk˙ oat. To this group belong the Ha’mats’a, the crane, the Ha maa, grizzly bear, and the Nū’tlematl. The first, second, and third of these are the “man-eaters.” The other groups are the following:

2. K˙ōk˙oski’mo, who are formed by the old men.

3. Māa’mq’enok˙ (the killers), who are formed by the young men.

4. Mō’smōs (the dams), the married women.

5. K˙ā’kiao (the partridges), the unmarried girls.

6. Hē’melk˙ (those who eat continually), the old chiefs.

7. K˙ēki’qalak˙ (the jackdaw), the children.

Every one of these groups has its separate feast, in which no member of another group is allowed to partake; but before beginning their feast they must send a dish of food to the Hāmats’a. At the opening of the feast the chief of the group—for instance, of the K˙ā’kiao—will say, “The partridges always have something nice to eat,” and then all peep like partridges. All these groups try to offend the Mē’emk˙ oat, and every one of these has some particular object by which he is offended. The grizzly bear must not be shown any red color, his preference being black. The Nū’tlematl and crane do not like to hear a nose mentioned, as theirs are very long. Sometimes the former try to induce men to mention their noses, and then they burn and smash whatever they can lay their hands on. For example: a Nū’tlematl blackens his nose. Then the people will say, “Oh, your head is black!” but if somebody should happen to say, “What is the matter with your nose?” he would take offense. Sometimes they cut off the “noses” of canoes because of their name. The Nū’tlematl must be as filthy as possible.

Sometimes a chief will give a feast to which he invites all these groups. Then nobody is allowed to eat before the Hā’mats’a has had his share and if he should decline to accept the food offered to him, the feast must not take place. After he has once bitten men, he is not allowed to take part in feasts.

The chief’s wife must make a brief speech before the meal is served. She has to say, “I thank you for coming. Be merry and eat and drink.” If she should make a mistake by deviating from the formula, she has to give another feast.

The first of these classes, the Me’emk˙oat, are a real nest of secret societies. I failed to gain a full understanding of this subject, which offers one of the most interesting but at the same time most difficult problems of Northwest American ethnology. I am particularly in doubt as to in how far the secret societies are independent of the clans. It seems to me, from what I was able to learn, that the crests of the clans and the insignia of the secret societies are acquired in the same way. They are obtained by marriage. If a man wants to obtain a certain carving or the membership of a secret society, he must marry the daughter of a man who is in possession of this carving or is a member of the secret society; but this can be done only by consent of the whole tribe, who must declare the candidate worthy of becoming a member of this society or of acquiring that crest. In the same way the chieftaincy of one of these societies devolves upon the husband of the chief’s daughter. If the chief of a certain clan or of a secret society has no daughter, a sham marriage is celebrated between the chief’s son and the future chief. But in some instances, the daughter or son succeeds immediately the father.

The ceremonies are as follows. When it has been decided that a man is worthy of acquiring a crest, he sends messengers to his intended wife’s father to ask his permission to marry the girl. If the father consents, he demands fifty blankets, or more, according to his rank, to be paid at once, and double the amount to be paid three months later. After these two payments have been made, the young man is allowed to live with his wife in his parents-in-law’s house. There he must live three months, and, after having paid a hundred blankets more, is allowed to take his wife to his home. Sometimes the girl’s father receives as much as five hundred blankets in the course of time.

When the young man comes to live in his father-in-law’s house, the latter returns the fifty blankets which formed the first installment of the payment for the girl. At this time the young man gives a feast (without giving away blankets), and on this occasion the old man states at what time he intends to return the rest of the payment. During this feast the young man rises, and in a long speech asks his wife’s father to give him his crest (carvings) and name. The father must comply with this request, and announces when he is going to transfer his rank and dignity. This is done at a great festival. I am not quite sure whether the whole tribe, or the clan alone, takes part in it. The father-in-law takes his copper and formally makes it over, together with his name and carving, to the young man who presents the guests with blankets.

These facts are derived from information which I obtained in Oumta’spē (Newetti), Fort Rupert, and Alert Bay, and from a thorough study of the traditions of these tribes, in which the membership of secret societies and carvings are always obtained by marriage. Notwithstanding this, the man who is thus entitled to become a member of the secret society must be initiated.

The members of these societies, when performing their dances, are characterized by headdresses and certain styles of painting, some of which are represented in Figures 11–20, as I found them used by the Tlatlasik’oa’la.

The most important among them is the Hā’mats’a [derived from ham, “to eat”]. I have described his initiation in the first number of the “Journal of American Folk-Lore” [Boas 1888c:58], and shall confine myself here to a brief description of his attire. The new Hā’mats’a dances four nights—twice with rings of hemlock branches, twice with rings of cedar bark which has been dyed red. Strips of cedar bark are tied into his hair, which is covered with eagle down. His face is painted black. He wears three neck rings [head rings] of cedar bark arranged as shown in Figs. 11–13, and each of a separate design. Strips of cedar bark are tied around his wrists and ankles. He dances in a squatting position, his arms extended to one side, as though he were carrying a corpse. His hands are trembling continually. First he extends his arms to the left, then he jumps to the right, at the same time moving his arms to the right. His eyes are staring, and his lips protruding voluptuously. The new Hā’mats’a is not allowed to have intercourse with anybody, but must stay for a whole year in his rooms. He must not work until the end of the following dancing season. The Hā’mats’a must use a kettle, dish, and spoon of their own for four months after the dancing season is at an end; then these are thrown away, and they are allowed to eat with the rest of the tribe. During the time of the winter dance, a pole called ha’mspiq is erected in the house where the Hā’mats’a lives. It is wound with red cedar bark, and made so that it can be made to turn round. Over the entrance of the house a ring of red cedar bark is fastened, to warn off those who do not belong to the secret society. The same is done by the other secret societies, each using its peculiar ornament.

FIG. 11. Kwakiutl head ring for Hā’mats’a

FIG. 12. Kwakiutl head ring for Hā’mats’a

FIG. 13. Kwakiutl head ring for Hā’mats’a

FIG. 14. Kwakiutl attire for Mā’mak˙’a

Another society is called Mā’mak˙’a. The initiation of a new member is exactly like that of the Hā’mats’a. The man or woman who is to become Mā’mak˙’a disappears in the woods, and stays for several months with Mā’mak˙’a, the spirit of this group, who gives him a magic staff and a small mask. The staff is made of a wooden tube and a stick that fits into it, the whole being covered with cloth. In dancing, the Mā’mak˙’a carries this staff between the palms of his hands, which he presses against each other, moving his arms at the same time up and down like a swimmer. Then he opens his hands, separating the palms, and the stick is seen to grow and to decrease in size. When it is time for the new Mā’mak˙’a to return from the woods, the inhabitants of the village go to search for him. They sit down in a square somewhere in the woods, and sing four new songs. Then the new Mā’mak˙’a appears, adorned with hemlock branches. While the Hā’mats’a is given ten companions, the Mā’mak˙’a has none. The same night he dances for the first time. If he does not like one of the songs, he shakes his staff, and immediately the spectators cover their heads with their blankets. Then he whirls his staff, which strikes one of the spectators, who at once begins to bleed profusely. Then Mā’mak˙’a is reconciled by a new song, and he pulls out his staff from the stricken man’s body. He must pay the latter two blankets for this performance, which, of course, is agreed upon beforehand. The attire of the Mā’mak˙’a is shown in Fig. 14. His face is painted black, except the chin and the upper lip.

The Olala (Fig. 15) is another member of this group. The braid on the right side of his head is made of red cedar bark. He also wears a neck ring, and strips of bark tied around his wrists and ankles. This figure is particularly remarkable, as the Tsimshian designate by this name the Hā’mats’a. Undoubtedly the Olala was acquired by them through intermarriage with the Hēiltsuk (erroneously called Bella Bella). They call the Olala also Wihalai’t (= the great dance).

The Lâ lenoq represents the ghost. He wears black eagle feathers (Fig. 16) in a ring of white cedar bark, to which fringes are attached which cover his face. He wears shirt and blanket, and a plain neck ring made of red cedar bark, … without any attachments. He carries a rattle (Fig. 17), which represents an eagle and is about a foot long. He does not dance, but lies down, only shaking his rattle.

The Sī’lic (Fig. 18) when dancing carries a long tube of softened kelp, closed at one side by a piece of wood, in his mouth. Suddenly he begins to blow it up, and the tube begins to grow out of his mouth, representing a snake.

The Ts’ē’k˙ois (Fig. 19) carries a great number of small whistles imitating the voices of birds. The Tlē’qalaq is represented in Fig. 20. He wears a raven headdress, and his genius is the spirit Wi’nalakilis. The latter lives on the sea, continually traveling in a boat. If a man happens to see him, he falls sick. Wā’tanum, another figure of these dances, wears a beard of red cedar bark, rising from the middle part of his forehead. His face is painted all black.

All these figures belong to the Mē’emk˙oat, every one representing a class protected by a certain spirit. As the meaning of these dances is kept secret by the societies, it is extremely difficult to obtain any information as to their significance. Each figure has a song peculiar to itself; but these songs, of which I obtained a considerable number, do not convey any information, as they are nothing but boastful announcements of the power and renown of each figure.

FIG. 15. Kwakiutl attire for Olala

FIG. 16. Kwakiutl attire for ghost dancer

FIG. 17. Kwakiutl ghost dancer rattle

FIG. 18. Kwakiutl attire for Sī’lic

FIG. 19. Kwakiutl attire for Ts’ē’k˙ois

FIG. 20. Kwakiutl attire for Tlē’qalaq

FIG. 21. Kwakiutl Nō’ntlemkyila mask

I indicated above that each of these figures has a peculiar way of dancing. A description of one of these dances may be of interest. Unfortunately I did not see it myself, but the information was obtained from a native whom I have reason to consider trustworthy. He said:

“During the dance Tsā’ek˙a whistles Ts’ē’koityala, which makes those who hear its sound happy, and Tliqiqs are frequently used. When the dance To’quit is to be performed, these whistles are heard in the woods and in the dancing house. A curtain is put up near the fire, separating a small room from the main hall, and in the evening all assemble to witness the dance. Several dancers hide behind the curtain, while others beat time with heavy sticks on the roof and on the walls of the house. During this time the whistles are silent; but as soon as the men on the roof stop beating time, the whistles are heard again. Now the audience begin beating time with sticks, at the same time singing, ‘A! Ai! ai! ai! aia aia!’ the tone being drawn down from a high key, down through an octave. Then four women make their appearance, their hair combed so as to entirely hide their faces. They go around the fire, and disappear behind the curtain. After four songs are sung, the chief declares that they have disappeared in the woods.

“The following day everybody—men, women, and children—is invited by one man or another, and they dance with masks. The next morning all go into the woods to look for the four women. They sing four new songs, and then the women make their appearance. They have become the Mā’mak˙’a, Kō’minok˙s, Hā’mats’a, and Tō’quit. The latter moves only very little when dancing. She holds her elbows pressed firmly against her sides. The palms of her hands are turned upward, and she moves them a little upward and downward. She sings, ‘Ya, ya, ya!’ and wears a necklet of hemlock branches. The four women next go home, accompanied by the crowd. When Tō’quit enters the house, the audience beat time with a rapid movement. She begins to dance; and when, after a short time, she cries, ‘Whip, whip, whip’ the people stop singing and beating time. Four times she runs tripping around the fire, forward and backward, holding her hands as described above. Then she turns around, and moves her arms in the same way as Mā’mak˙’a (see p. 50). Three times she opens her hands, trying to obtain her whistle from her spirit, but she does not succeed until the fourth time. She whirls the whistle against the people, who immediately stoop and cover their heads with their blankets, continuing to beat time. After a short time they uncover their faces to see what Tō’quit has been doing. It is supposed that meanwhile her genius is with her, and as a sign of his presence she holds a huge fish in her hands. She then takes up a knife and cuts it in two. Immediately it is transformed into Ci’tlem, the chief of the double-headed snakes. It grows rapidly in length, moves along the floor, climbs the posts of the house, and finally disappears on the beams.

“Now the audience begin once more to beat time, covering their faces. On looking up, they see Nō’ntlemkyila by the side of the Tō’quit, dancing and whistling. Suddenly a gull alights on his head, and soon rises again, carrying his head.”

A few specimens of the Nō’ntlemkyila are in the collection at Berlin, and one more I have seen in Washington. It is a small wooden figure, rudely carved, with moveable arms and legs. The figure is perfectly flat, being shown only in front view. The head is a flat disk (fig. 21), fastened by means of a pin to the body. The eyes are narrow, and two broad lines made of mica run vertically downward below the eyes. The hair is made of bushels of human hair. Numerous mechanical devices of this kind, moved by invisible strings, are used in the winter dances.

The winter dance is concluded by the Tsā’ek˙amtl (= Tsā’ek’amask). This concluding ceremony I found in use as well among the Wik’ē’nok˙ as among the Tlatlasik˙oala and Kwakiutl. The first call it Ha’stemitl; the last Haialikyauae. When the time of this dance approaches, the Wik’ē’nok˙ erect a large scaffold in the middle part of the rear wall of the house, on which Ha’stemitl is danced by a chief’s daughter. The scaffold is built by four chiefs. Its posts are tied together with red and white cedar bark. A shaman stands in the door of the house, his duty being to announce the arrival of the dancer. Another sits in the left rear corner on the platform of the house, playing the drum. Two more stand to the right and left of the scaffold, and move their hands slowly toward the dancer. When the dancer enters the house, the spectators must cover their heads with their blankets. Whoever does not obey this law must pay her a certain number of blankets. The spectators sit in the front part of the house, and accompany her dance with songs and beating time. The scaffold is destroyed after Ha’stemitl has danced four nights. This is the end of the winter dances; and neither the Hā’mats’a nor the Nū’tlematl, the Mā’mak˙’a, nor any of the other figures are allowed to continue their practices, their privileges only reviving at the beginning of the following dancing season.

Reprinted from Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie, vol. 3, pp. 7–15, 1890.

1. k˙ a guttural k, almost kr. q the German ch in Bach. sl an exploded l. [Boas’s 1890 transcriptions were not always accurate. By 1898 he had improved and had adopted different values for some symbols (Suttles, pers. com.)—Ed.]