Читать книгу A Wealth of Thought - Boas Franz - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

Welcome!

Greetings! O people of all tribes.

Our thanks that we have come together in this great house.

Our thanks that we have come to view the regalia of our predecessors, the works of our past chiefs.

And, so we have come here to gather, O people of all tribes.

So that we can come to look.

You are proud, O chief—you are proud of the treasures of your ancestors, of those things that we have come to see in this great house.

I have said it!

I have said it, O chiefs.

Why should we not be proud of these things for they have been saved so that we can see them.

That is it!

That is it! O people of all tribes.

—Speech in Kwakwala by Adam Dick, translated by Bobby Joseph, a recording of which welcomed visitors to the American Museum of Natural History’s exhibition “Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch.”

In October 1991 a new exhibit opened at the American Museum of Natural History. “Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch” featured the artworks that George Hunt had collected for Franz Boas at the turn of the century. At the opening, two great-grandsons of George Hunt, Bill Cranmer and Tony Hunt, stood before a crowd of hundreds of staff and visitors and proudly voiced the sentiments expressed earlier by Adam Dick in his welcoming speech.

This opening ceremony was by any definition an historic moment. More than forty Kwakwaka’wakw from Vancouver Island had traveled to New York City to validate an exhibition celebrating their ongoing artistic and ceremonial traditions.1 A leitmotif of the event was the tremendous service Boas had performed for the Kwakwaka’wakw people by recording and publishing their histories and preserving for all the artistic treasures on display at the American Museum. Descendants of Boas spoke warmly of their continued relationships with the Kwakwaka’wakw whose culture had dazzled their distinguished ancestor and continues to dazzle later generations.

I sat listening to the speeches, wondering what Boas would have thought had he been present. As his letters reveal clearly, he had a great love for these people whose culture he feared was about to disappear. He was especially fond of George Hunt, a gentle, quiet man whose brilliance has never been adequately acknowledged.2 Here, in the museum where Boas had worked for ten years trying to record for posterity the complex nature of Kwakwaka’wakw culture, were descendants of his Native friends, as well as two people he had known personally, Agnes Hunt Cranmer and William Hunt, who praised his efforts and honored his legacy. A man of immense social conscience and personal integrity, Boas had produced a vast body of scholarship informed by a commitment to prove the equality of all human beings and to encourage respect for and understanding of different traditions. Had his ghost been present in the museum’s Hall of Ocean Life where the opening ceremony was taking place, he would, I think, have been pleased. The people of New York City finally had the opportunity to observe the truth of his premise that all cultures and their material manifestations are worthy of admiration and esteem.

My first encounter with Boas came when I was in graduate school in the 1970s and read his lengthy—seemingly endless—descriptions of Kwakwaka’wakw art and culture. For someone intent on obtaining the truth about a topic, Boas was, frankly, frustrating. He provided abundant information, but never seemed to tie it up with a conceptualizing ribbon into a neat package that would enable me to understand the baroque art of the Kwakwaka’wakw. Moreover, his book Primitive Art (1927) seemed to me obscure, tedious, and of limited usefulness for my academic investigations.

Later, while researching a book on the American Museum of Natural History’s Northwest Coast Indian art collection (Jonaitis 1988a), I read his correspondences with George Hunt, John Swanton, and others and discovered behind all the scholarship a passionate, sympathetic, very real man. These letters and the wealth of materials on the Kwakwaka’wakw that Boas and Hunt left in the American Museum’s archives then became the source for documenting the artworks exhibited in “Chiefly Feasts.”3 My earlier frustration over Boas’s unwillingness to theorize and draw conclusions had turned to admiration for his devotion to meticulous documentation of the Kwakwaka’wakw, for his untiring activities aimed at collecting Kwakwaka’wakw art and artifacts, and for the social commitment that informed all of his anthropological endeavors.

This is a timely moment to evaluate Boas’s contributions to “primitive art,” for many of the points he makes correspond to concepts put forth by the so-called “new art historians” who reject the hegemony of western art styles, the isolation of art history from economic and social history, and the hierarchical and elitist divisions between high and popular art.4 As will become clear in this book, Boas’s writings on art reveal that such concepts are not new: for one who believed in the equality of all human cultures, art could not be considered inferior or superior. Moreover, his conviction that a group’s art style arose in part as a result of its cultural conditions and history contradicts the notion of an art existing in isolation from social and economic factors. And, by treating all art, by women and by men, as of equal significance, he effectively thwarts any concept of “high” art.5

Decolonization and the efforts of Native people around the globe to control their historical representation and cultural property have inspired a rethinking of the anthropologist’s role.6 Contemporary critical theorists tend to reject classics and canons, which they view as embodiments of entrenched, male, Euro-American power and thus impediments to the liberation of previously stifled voices. To make room for these new voices, it is often necessary to dethrone old authorities. It would be easy to consider Boas, often called the “father of American anthropology,” as a prime candidate for such dismissal. Indeed, some of what he wrote deserves critical analysis; however, a careful reading of his work on Native American art suggests that we take a more nuanced view. I propose that in the writings included in this volume, premised as they are on a resistance to premature theoretical closure and an egalitarian ideology, Boas created the space that Native people could ultimately occupy to assert their own voice.

It is appropriate to reassess Boas’s writings from the perspective we have gained as a result of the current crisis in representation and the reconsideration of the nature of art history and anthropology. Indeed, my own reading of his work has changed over the past several years from the moment I embarked on collecting his articles on art history for republication.7

This book has had a long history. In 1985 Janet Catherine Berlo invited me to participate in a College Art Association panel in Los Angeles on “Reevaluating Our Predecessors: Ethnographic Art Historians Look Back,” intended to assess, with an historical perspective, the contributions of some of the early interpreters of Native art. Later on that year, I was on another panel chaired by Berlo, “Native American Art History: Reassessing the Early Years,” held at the Native American Art Studies Association meeting in Ann Arbor, Michigan. I spoke at both meetings on the political dimensions of Franz Boas’s art history.8 I found his art history so interesting that I decided to edit a book of his essays.

Preparing the exhibit for “Chiefly Feasts” consumed much of the next several years and I had to put the Boas project aside. Finally, in 1992, the quincentennial of Columbus’s “discovery” of America and a year profoundly meaningful for Native Americans as the country reevaluated its history in light of their seminal role, I returned to it. The heightened consciousness of the historical relationships between Natives and non-Natives so prevalent that year motivated me to think more critically about how Boas represented Indian art. Insights derived from recent scholarship contributed additional dimensions.9 When I reread these articles in preparation for their publication, it became clear that many resonated with contemporary critical thought and the continued vitality of Kwakwaka’wakw artistic and cultural traditions.

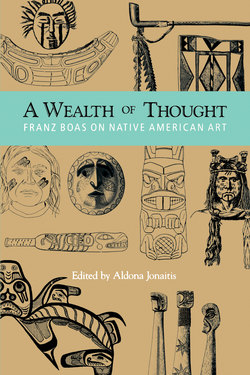

I have framed this collection of articles, written between 1889 and 1916, with an introduction discussing the development of Boas’s art history ideas and a postscript. The introduction connects the essays reprinted here to portions of his classic Primitive Art and positions them in their historical moment. Because every later scholar of Northwest Coast art is, in one way or another, indebted to Boas, in my concluding essay I demonstrate the profound impact he has had on twentieth-century studies of Northwest Coast art. The relevance of his writings still today and the respect with which he is viewed by modern-day Kwakwaka’wakw demonstrate that his work complements the new voices of liberty. I think he would have recognized and delighted in those voices, loud and clear, at the opening of “Chiefly Feasts.”

In editing this volume, one of the most difficult problems the publisher and I encountered was how to handle the orthography of Boas’s early writings. The articles reprinted here contain numerous words from native languages, particularly Kwakwala, the language of the Kwakwaka’wakw. Because over time Boas changed his orthography, we initially thought it would be useful to transcribe Native terms into a common orthography such as that developed by the U’Mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, British Columbia. The difficulty of accomplishing this and its potential for confusion convinced us to take a different approach. In order to be faithful to the original texts, we have published Native words just as they appeared in Boas’s text.

The figures have been renumbered for this volume, and in one case—“Primitive Art,” chapter 8—the illustrations have been dropped to avoid duplication with other articles. Corrections or other alterations to achieve consistency in style are minor in nature and were kept to a minimum. I have omitted some of the italic type used for proper names in the original articles and have provided an occasional emendation to the text in brackets.

A very important book on Boas came out after my essays were in production and I would like to bring it to the reader’s attention. Franz Boas, Ethnologe-Anthropologe-Sprachwissenschaftler: Ein Wegereiter der modernen Wissenschaft vom Menschen [Franz Boas, ethnographer-anthropologist-linguist: a pioneer of the modern science of man] (1992) catalogues an exhibition on Boas at the Berlin State Library from December 17, 1992, to March 6, 1993. It contains essays by Michael Durr, Erich Kasten, and Egon Renner on Boas’s anthropology, ethnographic methodology, and role in the development of American anthropology. Of particular interest to the present study is Erich Kasten’s “Masken, Mythen, und Indianer: Franz Boas’s Ethnographie und Museumsmethode” [Masks, myths, and Indians: Franz Boas’s ethnography and museology] (pp. 79–102). The exhibition included letters, photographs, publications by Boas and his students, and artifacts Boas acquired from the Inuit and Kwakwaka’wakw, as well as contemporary Northwest Coast art.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank several colleagues who willingly read this manuscript and made excellent and valuable suggestions for improving it. First, I express my deep appreciation for the time and energy my two art historical colleagues and close friends Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips devoted to these pages. Bill Holm and Wayne Suttles also read the manuscript and made extremely useful comments. In addition, I wish to thank other colleagues who read all or parts of the work: Michael Ames, Douglas Cole, Stanley Freed, Ira Jacknis, Arnold Krupat, Herman Lebovics, and Esther Pasztory.

Jay Powell offered useful advice on the orthography, and Wayne Suttles gave me a great deal of help in trying to adhere as closely as possible to Boas’s original spelling, while correcting obvious typographic errors.

Several individuals assisted in reproducing the illustrations for the book, and I thank them for their good work: Craig Cheset, Betty Derasmo, Dennis Finnan, and Joel Pollick. I would also like to express my appreciation to Geralyn Abinader for her help in coordinating this project. And, as always, let me thank my good friends and esteemed colleagues at the University of Washington Press.

1. The people whom Boas called the Kwakiutl today prefer the term Kwakwaka’wakw, which means “speakers of Kwakwala.” In this essay I use the preferred term.

2. The Kwakwaka’wakw elders who remember George Hunt describe him as distinguished and quiet; his brilliance is evident in his meticulous scholarship and thoughtful correspondences.

3. My two research assistants, Stacy A. Marcus and Judith Ostrowitz, did most of the archival work on these artifacts. They were assisted at different times by Peter Macnair, Gloria Cranmer Webster, and Wayne Suttles.

4. Ruth Phillips (1989) has recently elegantly demonstrated the new art history’s applicability to her study of Huron art. For more on new trends in art history, see Baxandall 1974, Belting 1987, Preziosi 1989, Hiller 1991, Berger 1992, and Phillips 1992.

5. For several interesting essays on new perspectives on “primitive art,” see Hiller 1991.

6. See the following for useful discussions of recent trends in anthropology: Ames 1992, Atkinson 1990, Clifford 1987 and 1988, Clifford and Marcus 1986, Geertz 1988, Kuper 1988, Marcus and Fisher 1986, Manganaro 1990, Maranhao 1990, Sanjek 1990, and Rosaldo 1989.

7. Through this review, I hope to contribute to the ongoing reassessment of the positive contributions anthropology and anthropological art history can make. Some scholars writing in Recapturing Anthropology: Working in the Present (Fox 1991) suggest means by which anthropology can usefully contribute to knowledge, while discarding elements no longer acceptable. Joan Vincent (1991:47) suggests that an historical analysis of early anthropologists like Boas, which connects their work to their social and political period, “advances an assessment of the critically distinctive, but many-layered relationship between anthropology and colonialism.” She urges in particular revitalizing the “classics” of ethnography by careful scrutiny of the texts in this kind of historical and contextualizing fashion. Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1991:39) suggests that anthropologists reassess the value of past ethnographic research and writing, “with a fair tally of the knowledge anthropologists have produced in the past, sometimes in spite of themselves.” In this book, I attempt to respond to these challenges. In the first essay, I review the development of Boas’s art history ideas and position them in their historical moment; in the concluding article, I demonstrate the profound impact Boas has had on twentieth-century studies of Northwest Coast art.

8. Berlo then edited a collection of papers from these two sessions, which became the book The Early Years of Native American Art History: The Politics of Scholarship and Collecting, published by the University of Washington Press in 1992.

9. For some of the recent works on postmodernist theory, see Alexander and Seidman 1990, Jencks 1991 and 1992, Kroker 1992, MacCannell 1992, West 1989, Harvey 1989, and especially Jameson 1991. For some discussions of postmodernism and Native cultures, see Todd 1992 and Townsend-Gault 1992.

In an essay in the amusingly titled book Zeitgeist in Babel, Charles Jencks (1991:19–20) tabulates a series of concepts that embody the differences between modernism and postmodernism. Thus, in contrast to the holistic nature of modernist writings, postmodernist ones are piecemeal; the straightforward is contrasted to the hybrid, simplicity to complexity, purist to eclectic, and harmonious integration to collage and collision. In a radio interview with Gayatry Chakravorty Spivak, moderator Geoffrey Hawthorn reflects upon the situation: “… these are confusing times, in which older universal traditions and certainties seemed, even though recently to be quite solid and reliable, no longer to offer the same security.… We can never connect, we can certainly never know that we connect with the things that there are in the world.… All we can know is what we say about the world—our talk, our sentences, our discourse, our texts” (Spivak 1990:17). Ames (1992:14) suggests a more moderate position: “The two extremes are to be avoided: the imperialist assumption that the scholar … has a natural or automatic right to intrude upon the histories and cultures of others ‘in the interests of science and knowledge’; and the nihilistic postmodernist claim that all knowledge is relative, all voices are equal.”