Читать книгу A Legacy Unrivaled - Boz Bostrom - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеThe date was November 19, 2012. It was an unseasonably warm late-fall morning when I arrived on campus. It was pretty much like any other Monday, with students and professors alike walking to their classrooms. As I pulled into the parking lot next to the Palaestra, the university’s athletic facility, I noticed that the blue ’01 Cadillac was in its usual place, parked next to the building as it always was.

I walked in the side door of the Palaestra and ascended the stairs. As I walked down the drab hallway, I found it to be oddly quiet. Several coaches were already in their offices, but they were keeping to themselves, almost deliberately so. As I approached the final office on the right, I saw that the door was open, as it usually was.

I gently knocked twice and, much more softly than usual, announced my presence. “Good morning, John. How are you?”

I was met with a tired expression and a soft voice. “I’m okay.”

“Did you talk to Frank yet?” I inquired.

“Yeah. I just sent him an e-mail.”

I hesitated and then asked, “Did you tell him your decision?”

The decision. It was one that all coaches face at some point: retire or come back to coach another year. But with John Gagliardi, the stakes were even higher.

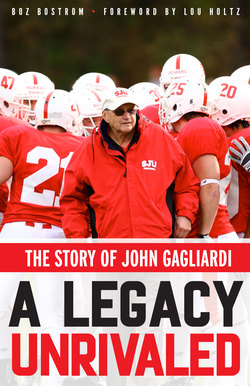

He had been a head football coach for seventy years. For the last 64 of them, he had coached at the collegiate level, 638 college games in all. His 489 victories were an incredible 80 more than any other college coach, ever, regardless of division. His teams had earned 30 conference championships and four national championships. His players had earned 114 All-American awards, and along with Florida State’s Bobby Bowden, John was the first active coach to be enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame. The Division III equivalent of the Heisman Trophy was named after him.

John had accomplished all these things with a unique style that emphasized precision, preparation, and humanity over brute force and intimidation. But perhaps his most important accomplishment was the role he played in the development of thousands of young men.

He repeated to me the message he had passed along to Frank, the local beat reporter whom John wanted to break the news. “Yeah. I told him that I’m not going to be there.”

Eighteen years earlier, I had walked off the field for the final time as a member of the Saint John’s University football team. A lot had happened since then. I earned a bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and CPA license. I worked for the largest accounting firms in the world, including the now-defunct Arthur Andersen. I got married, became a stepdad, and had two children of my own.

While my work as a CPA satisfied me and paid for my trips to California’s wine country, it did not consistently inspire me. I found that the favorite parts of my job had always been teaching and mentoring, and I began to explore how I could make a career out of doing those two things. I contacted my alma mater to inquire about a job as a professor, and after learning more about what it would entail, I fell in love with the idea. A couple months later, I signed a faculty contract that slashed my salary in half and gave me a 160-mile round trip commute. I was a professor at the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University, and I couldn’t have been happier.

My first semester back on campus was in the fall of 2004. I was fairly disciplined in those days, and many mornings I would exercise in the Palaestra before heading to my office. On my way out of the athletic facility, I would walk past John’s office. For the first few months, his office door was almost always shut; it was football season, after all.

Gerry Faust and George Korbel carry John off the field after a victory on homecoming weekend in 1962. Saint John’s University.

But one day when the season had finished and I once again found myself walking down the hallway toward his office, the door was wide open. I decided to reintroduce myself.

“Hi, John. I’m Warren Bostrom. I used to play for you.”

“Warren!” he boomed as loud as his soft voice would allow. “I know who you are. You played guard for me in the early nineties.”

He had coached more than two thousand players at that point in his career, so the fact that he remembered me caused my face to light up and my chest to swell with pride. He continued, “And I heard that you returned as a professor. I’ve had a lot of things happen in my career, but this is the first time one of my players has done that.”

For the next ten minutes, John and I got caught up on each other’s lives. Well, I should say that he got caught up with my life. Where do you live? In the Cities? That’s quite a drive: why don’t you move up here? Are you married? That’s great. How many kids do you have? Why did you come back to teach? How do you like it?

A few times, I tried to ask him a question about himself or football, but he quickly answered and then returned with a question about my life.

Running late, as usual, I had to excuse myself. So we parted ways, he to do whatever it was he did in the offseason, me to lecture on the wonders of debits and credits.

A few days later, as I approached John’s office again, I figured I would just walk past. He peered up from his newspaper when he heard my footsteps coming down the hall. I made eye contact but didn’t break stride.

I feared I would be bothering him if I stopped to talk. After all, I was but an adjunct assistant professor, with less than a semester of service to the university under my belt. And he was the big man on campus, easily the most influential member in the 150-year history of the university. He had been featured regularly in the New York Times and USA Today and had graced the cover of Sports Illustrated.

When I got about two steps past his office, I heard him call out, “Warren!” Why did he want to talk with me again? We had gotten caught up just a few days earlier. I went back, stood in his doorway, and replied, “Good morning, John.”

I called him John now, just as I did when I was a player. He insisted on it. He had started coaching football when he was just sixteen years old—it was 1943, and he was the tailback for his high school football team. His coach was called to serve in World War II, as were many able-bodied men from southern Colorado, and the school principal was planning to shut down the football program. Not wanting that to happen, John asked if he could coach the team. The principal agreed, and John was suddenly in the position of coaching his peers. He figured he couldn’t ask his own teammates to refer to him as “Coach,” so his first-ever players referred to him as “John,” and that never changed.

In this second meeting, John and I talked for a while, until I needed to go teach. The next time I walked past, we chatted for about fifteen minutes before I had to scurry away. It was always me breaking off the conversation and him delaying my exit, periodically even following me out the door to prolong our discussion, if only for a minute.

On days when I did not have to teach, I would sometimes stop by in the morning and stay for an hour or two. We would talk about every subject under the sun, and on rare occasions I could even get him to talk for a few minutes about football.

Some days I would find a current player in John’s office, other days a former player, and some days a potential future player, a recruit. Or perhaps I would find another coach, a member of the campus’s monastery, or an employee of the university. But the dynamics never changed. John asked the questions, and his guest did the talking.

But when John did talk, he made you laugh with his seemingly endless array of one-liners. Once, when he was in his early eighties, he said earnestly, as if to confide in me, “Warren, I have decided I have reached the point where I can only coach for one or two more …decades.”

Of all the days I spent in his office, there is one I will never forget. As I walked down the hallway, I heard voices coming from his office. I was intrigued to see with whom he was holding court that day. As I drew closer, I heard something unexpected: a female voice. That didn’t happen very often.

As I reached his doorway, I heard the familiar “Warren!” ring out, beckoning me to enter. Once inside his office, I discovered that the female he was talking to was a janitor.

I thought to myself, “Why is a man of this stature talking with a janitor?” And, of course, he wasn’t doing much of the talking. He was listening, actively engaged in hearing her tales. He didn’t concern himself with their different standing on the food chain of occupations. He simply cared that she was a person, a person worthy of respect and friendship.

After years of telling these stories to my wife, my dad, or anyone else who would listen, I began to better understand the keys to why John had such success on the football field. And I realized that these keys could also be used to “win” in everyday life.

And so I decided to take a sabbatical from teaching and document what I was witnessing. Along the way, I obtained insights from more than two hundred of John’s former players, from the 1950s to the 2010s, from All-Americans to benchwarmers.

This isn’t my story. This is the story of John Gagliardi.