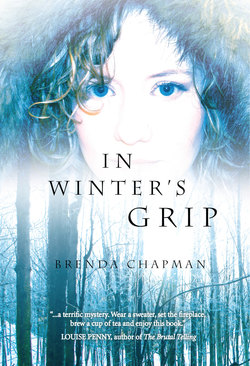

Читать книгу In Winter's Grip - Brenda Chapman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOUR

The next morning I woke early. I tried falling back to sleep, but too many thoughts were clamouring for attention. After a restless hour, I rose and dressed in a pair of blue jeans and a red fleece pullover before making my way into the kitchen. Claire had set up the coffee maker the night before with instructions to turn it on if I got up first. After two cups and a bowl of cereal and blueberries, I was ready to face the day and went in search of my boots and coat.

The rest of the household was still asleep when I stepped outside into a bitterly cold day. Sometime during the night, a north wind had blown away the cloud cover, and a high pressure system had pushed its way in. Already the sky was turning from black to midnight blue and frosted orange as the sun slipped over the tree line. Every so often weak, silvery sunshine glistened through the trees, casting slender lines of brightness in the snow. I’d gratefully accepted Claire’s offer of her parka the night before and nestled into its fur-lined warmth. The coat fit well even though I was not as tall or slender as her.

I was relieved when my car started after two tries. I let it idle while I cleaned off the roof and windshields with a snow scraper. As I worked, my breath came in moist, white puffs as though I were chain smoking. With the plummeting temperature, the car should have been plugged in overnight, but it hadn’t come with a block heater. It seemed negligent in this country, but the man who’d given me the keys hadn’t had many to choose from in his lot. This particular car had just been driven up from Florida by a businessman. If I hadn’t been in such a hurry to see Jonas, I’d have taken a taxi to a rental place in town, but I was too anxious to spend the extra hour driving into Duluth. The rental guy had assured me that the car would start no problem, but his confidence wasn’t much help with the frigid temperatures in Northern Minnesota.

The drive to Dad’s house took all of fifteen minutes. If the roads hadn’t been slick with ice, I’d have made it in ten. The route took me to the outskirts of the village, the road hugging the shoreline and winding slowly north. My car’s tires valiantly gripped the road as I crept at a turtle’s speed up a steep hill and deeper into the woods. Luckily, the plow had been around early and the road was passable. Only a few houses dotted this back road, small homes with smoke pouring out of the chimneys and wood stoves the main source of heat. If I opened the window and leaned out, the smell of wood smoke and pine would fill my nostrils like a love note from the past. There was a time when I knew every family along this road, and might still, if the town held true to form. Most of the older people in Duved Cove lived their entire lives in the same house, and their children married locally and moved into homes nearby. My generation was the first to go farther afield, to university then to towns and cities with better jobs.

Duved Cove had been a fishing village in the 1800s and a logging centre in the early 1900s. The mill was still operating, but on a much smaller scale than in its heyday. My father hadn’t liked working with his hands and had broken with tradition by becoming a cop, a profession Grandpa Larson had viewed with a jaundiced eye, but even he had to admit that Dad would have made a poor logger. As it turned out, Dad wasn’t much of a cop either. The year after I’d left for Bemidji State University to work on a chemistry degree, my father was implicated in a coverup of some sort and quietly dismissed from his duties. If he hadn’t had such a good reputation, and if all the higher ups in the chain of command hadn’t liked him so much, they might have made a harsher example of him for the benefit of the younger officers on the force. As it was, rumours of the dismissal were punishment enough in such a tight-knit community. Dad never told us the full story, and we knew not to press him for details. His dismissal was quiet enough that he was able to get a job as a customs officer at the Pigeon River crossing about an hour’s drive from our house. It was a job he’d held until Friday.

My father remained in the house where I’d grown up even after my mother died. He owned a good twenty acres of land that had never been developed—land handed down from my great-grandfather, along with our house on the north-east corner. The house I’d loved as a child, in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by woods and rock that led to the rocky shoreline of Superior. The house where my father had found my mother hanging from an attic rafter one cold October morning.

I slowed the car and fought to keep the memory from surfacing. My hands had been clutching the wheel, and I tried to flex my fingers. If I allowed myself to think about the horror of that day, I would never be able to make this journey—one I’d been unable to make when my father had been alive. I’d visited my brother twice, the last time when Gunnar was six, but I’d never made the trip to my parents’ house, even though Jonas believed it would help me to heal.

“I have nothing to heal from,” I’d said angrily, and Jonas had watched me with veiled eyes. I’d tried to appear unaffected. “I just have no reason to go back there. I’m over it.”

The last mile was almost too painful to bear, the big rock where I used to meet my best friend Katherine Lingstrom so we could walk to school together, the crooked tree Jonas and I had climbed, the path into the woods that led down to a sand beach where Billy and I had lain in the shadow of the woods. I took each landmark in with starved eyes. This was the part of me I’d shut away since my mother’s death.

I could see her in my mind’s eye, walking down the road, a cattail in her hand, twirling back to smile at me and tell me to hurry up. If I pretended time had stood still, if I believed hard enough...her hair had been white blonde like mine, and falling almost to her waist. She worn it braided, but the days she’d let it loose had seemed a gift. She had a smile and blue eyes that had warmed me always, even when she was trying to contain me. Back then, I’d been a carefree and careless child, rushing headlong into every situation. My disregard for rules had gotten me into trouble with my father over and over again. I’d rebelled against his harsh, unyielding nature that turned monstrous when he drank. My mother had been powerless to protect me, to protect herself from his anger. I’d loved my shy, tormented mother with my whole being, and when she’d killed herself, she’d killed any part of me that could forgive my father. And yet part of me needed to with childish desperation.

I was surprised to feel my cheeks wet with tears as I started up the long driveway to our house. I lifted my brimming eyes to my old bedroom window on the second storey on the right side of the house. The blind was halfway down, as if it couldn’t make up its mind. The symbolism was not lost on me. I parked the car and stepped outside. I’d come home at last.

I circled around to the backyard. The sun had risen above the treeline, and the snow had taken on a rosy hue to match the sunlight filtering through the trees. I purposefully averted my eyes from the woodpile and scanned the yard. Dad had kept it free of clutter. I could see poles in the ground where he’d planted tomatoes and beans in Mom’s vegetable garden. A concrete birdbath rose above the snow pile with a mound of ice capping its basin. Directly in front of me were a stand of birch trees and two spruce with birdfeeders hanging from the lowest branches. As I watched, a squirrel parachuted onto one of the feeders and scattered the last of the seed into the snow. Like so many properties in Duved Cove, there was no fence to encircle the yard except around the garden to keep out deer. I looked down. The ground had been trampled by a number of boot prints. I could only imagine what must have taken place after they’d found my father’s body.

I turned and walked slowly towards the deck. When I reached the bottom step, I hesitated with my glove on the railing. I forced myself to look. The snow was piled in uneven patches around the spot where my father had fallen. I could see red and pink through the layers, and it was an eerie feeling to know that this was his blood. The place he had met his maker. I moved closer and squatted in the snow. They’d dug around the area, probably looking for clues. As a crime scene went, it would have been a hard one to keep. Even now, the wind was blowing swirls of snow in intermittent gusts. I moved back towards the stairs, careful not to leave more footprints than necessary. I grabbed the handrail and leaned on it heavily as I maneuvered the icy steps. Once I reached the landing, I fumbled in my pocket for my keys. The key to this house was still on my keychain. I didn’t know why I’d kept it after so many years, but I had. I supposed it could be construed as more symbolism, if you were bent that way.

The yellow and black tape across our back door made me pause a second, but it would not stop me now that I’d come this far. I pulled the yellow tape aside and fit my key in the lock. It turned as if I’d used it every day for the past twenty years. The familiarity of the key’s weight in the lock brought back memories hooked onto feelings long forgotten. Once inside, I slammed the door shut and leaned against it with my eyes closed tight. I sucked in air like a drowning swimmer and tried to still my frantic heart.

“Mama,” I whispered.“Your Maja’s come home.”

My father’s kitchen had changed little since the last time I’d been in it. The same green linoleum on the kitchen floor, lifting a bit around the edges; the original tired oak cupboards; the old Frigidaire in the corner. A new rectangular pine kitchen table and matching chairs looked out of place in the otherwise drab room. I circled the space, trailing my fingers along surfaces. The house was still on its programmed heating cycle, and I heard the furnace kick in. I’d hardly noticed how cool it was until that moment. I heard the clock ticking loudly on the wall over the stove, the same clock that my mother had picked out of the Sears catalogue thirty years before. The room smelled stale, the dankness heightened by a mixture of cooking grease, overripe bananas and rotting potatoes, and I suddenly couldn’t wait to leave it. I went quickly down the darkened hallway into the living room. Here Dad had splurged on a new couch and leather recliners that encircled a big screen television. He’d acquired a state of the art sound system too that had place of honor on top of a shelving unit. The ornaments and pictures Mom had collected were gone, but lower down on the shelving unit, my father had placed a framed picture of himself and two buddies dressed in hunting gear and holding rifles. In the photo, Dad was grasping a handful of dead ducks by their feet and grinning into the camera.

I walked over and picked up the frame, staring into Dad’s face and trying to see any part of him that I could latch onto. I had no idea why I thought the essence of him would be captured in a photo when I’d never been able to find it in real life. He looked fit and ruddy-faced, as if time had held off aging him. His blonde hair had turned a soft white, cut in a layered style, and his eyes were still a deep vivid blue. I put his picture back next to framed photos of Gunnar. In the first, he is a baby in Claire’s arms, and in the second he is school age, grinning into the camera with his top front teeth missing.

New carpeting led to the stairs and up to hallway on the second floor—forest green with a pattern of tan swirls. It wasn’t thick enough to hide the creaks as I slowly climbed. I hesitated on the landing and watched dust dance in the sunlight seeping in through the slats of the metal blind that covered the window above my head. The same brown paneling I remembered lined the walls. It looked streaky in places, faded like well-worn leather shoes. The door to my parents room stood open, and I stepped inside. I don’t know what I expected to find, but it wasn’t this. The bed was gone, and in its place were a stationary bike, a rowing machine and an apparatus that had weights and pulleys for working out the upper body. Free weights lined the floor in front of bright blue mats like the ones we’d had in gym class. I jumped when I turned and saw myself reflected in a floor to ceiling mirror that lined one wall. My face was pale and my eyes tired. I looked like I needed a hot bath and a good, strong drink. Those would come later.

My father had taken Jonas’s old bedroom as his own. The double bed and oak headboard were new, but he’d kept the chest 33 of drawers and my mother’s hope chest. I crossed the room and tried to open the chest, but it was locked. I didn’t feel like searching for the key—not yet. The walls were washed-out beige, and I could make out the outlines of Jonas’s posters that Dad had removed without bothering to paint. The one on the far wall had been the famous poster of Farah Fawcett, the one with her sitting nearly sideways in a red bathing suit with her head thrown back and a smile the size of a quarter moon on her face. Jonas had had a crush on her that lasted the entire television run of Charlie’s Angels. A thick duvet covered the bed while curtains in a matching caramel colour hung at the window. If Dad had kept my mother’s ornaments and photos, they were tucked away out of sight, perhaps in the locked chest.

I walked past the bathroom and kept going to my own bedroom at the end of the hall. The door was shut. I took another deep breath and turned the knob. Once again, the room’s contents surprised me. My father had removed my bed and all my childhood things. In their place were piles of boxes and pieces of old furniture stacked against the walls, much like you’d find in an attic. The only item left in the room that I recognized was the faded rosebud wallpaper. All other traces of my occupancy were long gone or packed away out of sight. I moved closer and pried open the cardboard flaps of a large box, curious about what it held. Dozens of paperbacks were neatly arranged in rows, their covers glossy and brand new. I opened the large box next to it and found a boxful of hardcover books; the third box held Bibles, black covers with gilt lettering. Had my father become an avid reader? Had he turned to religion? I couldn’t remember that he’d ever sat down to read anything more than the newspaper, let alone consider theology in any form. In addition to the Bibles, there were mysteries, historical fiction and New York Times bestsellers, light escapist reading.

I straightened and walked over to the window to look at the streaked sky through the boughs of the old pine. I raised the blind and a swirl of light dust drifted around me like flour. Lowering my gaze, I looked across the yard at the trees at the end of our property. As a girl, I’d spent many hours daydreaming at my desk, which had been positioned in front of the window. For the first time since I’d entered the house, I felt like I’d found something of my own. I closed my eyes and imagined myself back in high school with nothing in front of me but a school assignment and possibilities.

If I hadn’t been so still, I might have missed the heavy creak of the loose floorboard on the stairs. I held my breath. A second creak even closer, and I exhaled slowly. I whirled around. Whoever had entered the house had done so without my hearing them. The half-open bedroom door seemed like an impossible distance away, and I knew I couldn’t get to it before the intruder reached the landing. I was cornered. My breathing was too loud in my ears, but I willed myself to stay calm. If the person creeping up the staircase meant me harm, I’d know soon enough.