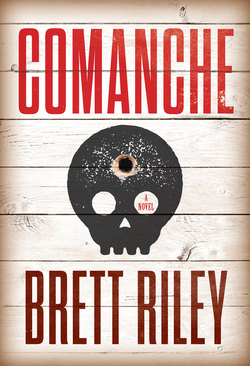

Читать книгу Comanche - Brett Riley - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Five

May 8, 2015—Comanche, Texas

Morlon Redheart finally seemed happy. He’s sick of landscapin, C.W. Roark thought, and Silky’s gettin too old to drag pallets around Brookshire’s. They need this. The contractors had installed the new front walk and lights and windows and an alarm system but left the depot’s more picturesque scrapes and dings alone. They laid a small concrete parking lot but didn’t bother with a light pole. The ambient light from Austin Street would suffice.

As the renovations progressed, Roark sometimes stopped on Austin and watched, leaning against his truck with his arms and ankles crossed. Gotta make sure Red gets a good picture when it’s finally time to run his article. The newspaperman had decided to make it part of a group. Other photos would show Old Cora—the authentic frontier cabin that had served as the original county courthouse and now squatted on the town square as if a bored god had scooped it out of the past and dropped it in the twenty-first century—and the Fleming Oak, the old gnarled tree in which a white boy had once hidden from a Comanche attack. Tourists eat that kind of shit for breakfast, especially the ones who think every town west of the Mississippi used to be like Dodge City or Tombstone.

As for the outbuilding, they installed no extra lights and protected it with only a padlock. Why bother with much else, when the best any thieves could hope for might be a big can of corn or a broken stool? Morlon had ordered the workers to toss all the old shit into the courtyard, where he stuffed smaller items into trash bags, larger ones into the bed of his pickup. He planned to haul it all to the dump.

One day, Roark stopped by as Morlon was dropping half a dozen pewter plates into a Hefty.

Hang on, the Mayor said. He pulled out the plates and then dug through the bag. He found a few more dishes, a set of tarnished forks and knives, a pair of busted cowboy boots, and a gun belt that looked older than Moses. Both the boots and the belt were stained with what might have been mud a century old. Roark spread these items on the ground. You find any other stuff like this?

Nope, Redheart said. Just trash.

Get somebody to clean these up, the mayor said, indicating the dishes and cutlery. Maybe we can hang ’em around the diner. Give the place more authenticity.

What about that cowboy shit?

When Roark picked up the boots and gun belt, he shivered. His arms broke into gooseflesh despite the heat. He dropped the junk and wiped his hands on his pants. Felt like stickin my hand into ice water. Maybe I’m comin down with somethin.

Redheart raised his eyebrows but said nothing.

Just put ’em back on a shelf, Roark said. I’ll figure out a place for ’em.

Redheart shrugged and resumed loading trash.

Roark left. Tomorrow, I’ll call around and see if anybody works on leather that old.

The next day, however, meetings took up most of his time. When he got home that night, he was exhausted, and he had forgotten all about the boots and belt.

After the building passed inspection, Roark announced the grand opening of the Depot Diner. It seated about as many people as your average Waffle House and served authentic Texas and Mexican cuisine, from family-recipe posole to Americanized dishes like chili cheeseburgers. The mayor and his family attended opening night, as did every Comanche bigwig Roark could beg, harass, or threaten. By the time these people brought their friends and neighbors, cars and pickups filled the parking area and the grass lot, with many more lining both sides of Austin Street. Patrons stood on the walk or sat on the new backless benches as they slapped mosquitoes, bullshitted, and waited for their tables.

No one paid any attention to the wind that sometimes kicked up when certain townsfolk stepped onto the depot grounds. And if the patrons noticed the way the air shimmered near the storage building, none of them spoke of it.