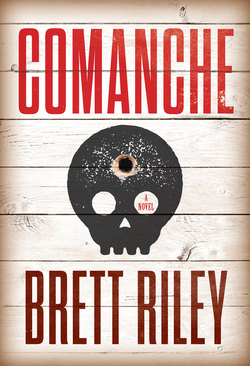

Читать книгу Comanche - Brett Riley - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter One

July 23, 1887—Comanche, Texas

P.D. Thornapple did not own a watch, but he believed it was roughly 2 a.m. when he saw the Piney Woods Kid lurking near the Comanche Depot. That sight would have alarmed P.D. any time. The Kid had earned his reputation as one of the bloodiest outlaws in central Texas by gunning down two sheriffs, a U.S. Marshal, a Texas Ranger, and enough private citizens to fill a boneyard. When you saw the Kid coming, you ducked behind the nearest building, and if you could not run—if, say, he showed up where you worked, where you stood the best chance of getting a little respect and enough cash for whores and whiskey—you kept your eyes on the floor and your mouth shut, and you prayed he would leave. But now P.D. Thornapple almost fainted because, in the early morning of July 23, the Piney Woods Kid had been dead for a week.

On the fifteenth, P.D. had been thinking about the way shit rolled downhill and how he always seemed to be standing at the bottom, stuck with the most sickening, degrading duties—sweeping up after the cattlemen with cow shit stuck to their boots, washing out vomit when drunks staggered over from the Half Dollar Saloon and mistook the depot for a privy, mopping up their piss after they passed out and soiled themselves, sometimes right on the platform. When randy young couples tried to do their business behind the dead house, P.D. chased them off. And when the Piney Woods Kid and Sheriff Demetrius McCorkle fought across the depot grounds two years ago, who had to scrub away all the blood from the woman the Kid took hostage, from the deputy he gut-shot, from the three men he executed at close range, from the Kid himself? Who had picked up a misshapen mass of tissue that turned out to be the end of McCorkle’s nose? P.D. wanted to quit, but begging his asshole brother for a job seemed worse than dealing with blood and shit.

So P.D. endured everything, even the dead house itself. A squat building ten yards from the depot, it looked new and downright inviting in the daylight, but at night it turned the color of old bones bleaching in the desert, its very presence pricking the base of his spine. Why didn’t the railroad just paint the goddam thing or burn it down?

But a raw eyesore worked just fine for the bosses, and the corpses did not care one way or the other. P.D. had been forced to load bodies into the dead house, to transport them onto waiting trains, to guard the building as if it held treasure instead of cold, stiff flesh. He checked the lock on its door twice every shift. Constant exposure should have rendered the place familiar, even banal, yet he had never shaken the feeling that something was inherently wrong with the whole idea of a dead house: a way station for cadavers, a hotel for stiffs. If only one of the day-shift men would quit or die so he could take their spot and never have to look at that building in the dark again.

P.D. had never been that lucky, though. He sat in the depot just after dark on the fifteenth when McCorkle’s runner, Deputy Rudy Johnstone, brought news that their posse had killed the Kid. It was the biggest event in Comanche County history, even bigger than when that son of a bitch John Wesley Hardin murdered Charles Webb back in ’74. Sheriff McCorkle and his riders trapped the Kid and his old Comanche companero in an empty cabin beside Broken Bow Creek late that afternoon. The outlaws and the posse shot at each other for fifteen minutes or so, until McCorkle got sick of waiting and set fire to the place. The Kid and the Indian escaped out the back, making it a hundred yards up the creek before McCorkle’s men rode them down. According to Johnstone, the outlaw’s torso looked like an old woman’s pincushion, and the Indian’s face had been shot clean away.

They could have let the Kid rot where he fell. They could have planted him by the creek. But no.

Sheriff wants to haul the carcass through town, Johnstone said. Maybe that way folks will finally stop talkin about how the Kid shot off his nose.

Of course. Revenge for the carnage and misery the Kid had wrought. Besides, the undertaker was out of town, so what was the hurry?

No one spoke of the Comanche’s corpse. Likely the white men had left it to the elements and scavengers, one more slaughtered and nameless dark skin among the thousands blanketing the land, some buried and some abandoned, their final resting places unmarked as if they were ants or scorpions crushed under pedestrian feet.

After Johnstone delivered his news, P.D. sat on the bench outside the depot and waited for the posse.

The insects thrummed around him like locomotive engines until, from town proper, came whoops and cheers and gunfire and, soon enough, the muted clop of hooves on dirt. P.D. looked at the moon—likely close to 10 p.m. McCorkle must have stopped at every shack and tent so folks could sing hosannas. Torches glowing in the distance grew closer. Individual men and horses coalesced from the shadows, McCorkle riding his gray at their head. A dozen mounted men followed, most hidden in the gloom, but there came Charlie Garner’s spotted roan, the one that looked like it was caught in its own snowstorm, and Shoehorn Wayne’s black mare. Roy Harveston’s chocolate gelding with the white star on its forehead. The half-wild pure-white horse Beeve Roark called Ghost. Rudy Johnstone walked in leading a mule on which a figure lay crossways, tied like a roll of carpet. Someone had thrown a saddle blanket over the body, but dusty, cracked, bloodstained boots hung uncovered off one side, pallid hands off the other. Without thinking, P.D. took off his hat. Beeve Roark glared at him and spat a thick stream of tobacco juice near his feet as the procession headed for the dead house.

Each of these men had stuffed a hatchet into his belt, except for Johnstone, who carried a hacksaw.

P.D. shivered. He dashed inside and grabbed his keys and a lantern. As he trotted back out, the keys jingled like a tambourine. The lantern cast pendulous, cavorting shadows across the grounds and the tracks. The posse had dismounted by the time he reached them. Most fell back into the shadows, faceless and ephemeral. McCorkle, Roark, Garner, Wayne, and Harveston flanked the door as some of the others untied the body. P.D. hung his lantern on a hook and unlocked the door. When they hauled the Kid into the dead house, P.D. caught a glimpse of the outlaw’s pallid face splashed with blood, eyes wide open and glazed.

Once the men and the corpse disappeared into the dead house’s dark maw, Garner and Harveston and Wayne and Johnstone followed. McCorkle nodded at Roark, took P.D.’s lantern off the hook, and walked inside. P.D. started to follow, but Roark pushed him back.

Well, P.D. croaked, I reckon you boys don’t need none of my help.

Roark spat in the dust and wiped his mouth on his shirtsleeve. I reckon not.

The faceless riders exited the building, saddled up, and rode away, murmuring among themselves. Then Roark stepped inside and closed the door.

P.D. lingered a moment, unsure of what to do or say. Reckon I better get back to my post. He walked away but managed only a few steps before a steady thuk thuk thuk emanated from the dead house. Such an everyday sound, like someone chopping wood two houses over, might have been comforting during the day, but there, then, it sounded awful, the sound of an emaciated, hollow-eyed man with corkscrew hair standing over a coffin in an open grave, hacking up a body and tossing chunks into a bag.

Goddam magazines, with their stories about grave robbers and folks gettin buried alive and such—enough to drive a grown man crazy.

Back inside the depot, under the lanterns’ warm glow, P.D. dropped the keys into their drawer. He went to the doorway and leaned against the jamb, watching the dead house. The lantern light flickered inside, shadows gamboling against the curtained windows. Soon P.D. returned to his desk and did not look outside again.

They wanted to prepare the corpse their own damn selves, so let em.

McCorkle and the rest left just before dawn. P.D. stood on the platform and watched them ride away. No one acknowledged him. They carried old flour sacks tied at the necks. P.D. believed he knew what those sacks held.

Two days later, P.D. passed the undertaker on the street and asked about the Kid’s funeral arrangements.

The old man looked puzzled. Funeral? he said, scratching his cheek with dirty fingernails. Hell, I ain’t even seen the body. Rudy Johnstone’s been braggin they butchered the Kid and throwed the pieces in three or four different cricks. But hell, you know how Johnstone likes to hear himself talk. It’s probably bullshit.

Now, at 2 a.m. on the twenty-third, most everyone in Comanche could be found in one of two places: home in bed or at the Half Dollar, listening to Johnstone tell about the Kid’s last stand, as he would likely keep doing as long as some sodbuster or cowpoke fresh off the trail offered to buy the drinks. Even free whiskey had not prompted Johnstone to reveal what the posse had done with the Kid’s body, though. Given what P.D. had seen a week ago, the undertaker’s story seemed credible. In any case, those fellas had taken the corpse off P.D. Thornapple’s hands, which suited him just fine. He lay on his cot behind the main office, pulling on a bottle of tequila and singing to himself, planning to do little else for the rest of his shift.

Then he sat up. A while back, Mr. Sutcliffe from the rail company telegraphed about an upcoming inspection of the personnel and facilities.

Hellfire. When did that old coot say he was comin?

P.D. went to the front desk and dug through the top drawer, where they kept all the important correspondence. He found Sutcliffe’s telegram three sheets from the top and scanned it.

In part, it read, WILL ARRIVE ON 23RD STOP.

Shit, P.D. said.

As the night man, it was his job to air out the dead house when fewer people wandered by to smell it, and he had not done it since that cursed night. The goddam place probably stunk to high heaven. If Mr. Sutcliffe smelled anything like Shot-to-Hell Outlaw or saw any stray drops of dried blood on the floor, that would be the last the depot would see of P.D. Thornapple, who would have to move back to the family ranch with his hulking, sharp-tongued brother and the asshole’s shrew wife and five runny-nosed brats. And, echoing the plight of mistreated younger brothers all the way back to Abel, P.D. would have to sleep in the barn because they were already stacking kids in the main house like cordwood. He took two long swigs of tequila—probably the last of the night, though he took the bottle, just in case—and grabbed his keys, grumbling.

P.D. walked out of the depot and turned left.

Someone stood in front of the dead house.

He dropped the tequila and the keys. The bottle hit the platform and rolled to the edge, where it teetered, the liquor gurgling out. P.D. ran and grabbed the bottle, saving about half the alcohol, and celebrated by taking another long gulp, Sutcliffe be damned. The liquor burned going down.

When he turned back to the dead house, the figure was gone.

P.D. tittered. You damn fool. Nearly jumpin outta your skin thataway. Probably just some cowboy from the Half Dollar with a head full of Johnstone’s tale and a bladder full of hot piss. Walked right by the outhouses in the dark, like folks sometimes do.

Go piss in the privy like civilized folks! P.D. shouted.

Lanterns hung from iron hooks on either side of the depot’s doors. He retrieved the keys and took one of the lanterns and held it high, swinging it back and forth. No further sign of the visitor. P.D. started across the lot.

Upon reaching the dead house, he unlocked the door and pulled it open. Sure enough, the place smelled—dank, like old leaves and damp earth, with undertones of meat gone bad. Grimacing, he pulled his shirt over his nose and found the block of wood the depot workers kept for propping open the door. After setting the block in place and putting the lantern on the floor, P.D. went inside and pulled back the curtains—dark ones made of some thick, rough-spun cloth that kept people from seeing the coffins the workers lay on the floor or, when too many people dropped dead, stacked on top of each other like packing crates—and opened the windows. Walking back outside, he let his shirt drop and breathed in fresh air. He hoped the stink would clear out by morning.

When he thought he could stand it again, he went in. The floor looked terrible. Once raw and unpainted but sanded smooth, the center of it now bore evidence of those hatchets and that hacksaw, small chunks gouged from the wood here and there, the marks of serrated teeth having dragged across the boards, as if demented children had broken in with their fathers’ tools and vandalized the place.

Well, I ain’t no goddam carpenter. I just hope a stray dog or a wolf don’t wander in and shit everywhere.

Against the far wall sat a pair of sprung, dusty boots with an empty gun belt coiled around them. They were covered in dark stains—water damage or dried blood or Lord only knew what. Next to them, a pile of clothes—filthy denim jeans, a pair of rancid socks, a wadded-up cotton shirt shot full of holes and stiff and stained dark, the frayed remains of a leather vest, a weather-beaten cowboy hat.

Hellfire, P.D. said.

He walked to the discarded clothes and picked everything up, struggling to keep hold of the lantern. He kept dropping items—a boot, the crusty shirt—and picking them up again until, cursing, he set the boots and gun belt on one of the supply shelves built onto the back wall. Just his luck, this shit would take more than one trip. On the way back, he would probably trip over a skunk and land on a cactus.

Carrying his burdens, P.D. wondered how to dispose of the clothes. Burn them? Bury them? Throw them in the street? Go down to the Half Dollar, and tell people they probably belonged to the Piney Woods Kid, and see who would buy him a drink for his story?

He walked outside.

The Piney Woods Kid stood ten feet away, between him and the depot, staring with gray and vacant eyes.

P.D. stumbled backward and swore.

The Kid could not be here. McCorkle had killed the shit out of him. The town—hell, half of Texas—had scorned and laughed at and dismissed the Kid, all those outlaw exploits already corrupted in people’s memories as little more than the sting of a particularly loathsome horsefly. Yet there the man stood, covered in dried muck that might have been mud or might have been blood. He wore the same clothes P.D. carried. An impossibility, but even beyond that, something seemed off. The Kid looked bleached, like a garment rotting in the desert sun. Stringy, oily hair framed his pallid face. His arms hung slack, his guns holstered.

Calm down. This ain’t the fella to spook.

P.D. tried to spit, but his mouth had gone dry.

The Kid stood silent, staring.

McCorkle must have killed the wrong man and claimed it was the Kid. No wonder the posse drove P.D. away from the dead house that night. How had the deputy managed to fool everybody at the Half Dollar? Somebody should have noticed. Maybe Johnstone’s mania scared them all shitless.

Damn McCorkle and Johnstone. Damn my luck.

Still, P.D. Thornapple did not intend to stand out here all night with some murderous asshole who was supposed to be worm food.

Jesus God, Kid, you scared the shit outta me, he said, his laugh rising in pitch until it disappeared. You better get on before old Noseless sees you.

Actually, if McCorkle had come along, that would have been just fine. Whatever got P.D. away from this maniac and back to his nice, safe cot. But you had to handle these gunfighter types a certain way, mainly by kissing their asses until they left.

The Kid said nothing. His eyes were the color of clouds on a moonless night.

In town, someone fired two shots in the air and whooped. P.D. jumped.

The Kid did not move.

Tiny slivers of spit and phlegm stuck in P.D.’s throat. He wiped his sleeve across his forehead, its fabric coarse on his damp skin.

Word has it you’re killed, he said, but I guess Johnstone’s tellin tall tales. That sumbitch always had a mouth on him.

Maybe an unkind word about the local law would afford P.D. some favor. The Kid had been standing there a full minute, maybe two, and had not even blinked.

That was some damn good shootin here, that day you took McCorkle’s nose. Them laws thought they had you, but you blasted right through ’em. Never seen nothin like it.

The Kid stared. He might have been someone’s displaced scarecrow.

P.D. shivered, even as sweat dripped down his forehead and coated his back.

Say somethin, he whispered. Don’t just stare at me thataway. Talk to me. Please.

The Kid seemed not to have heard.

Someone fired another shot near the main thoroughfare. Then they whooped again. Who was it, and what were they up to? If only P.D. were there, or anywhere else. The middle of the ocean would have been fine. The Kid had always been a motormouthed lunatic but seemed even worse now that he had turned mute. If only somebody, anybody, would come along. They could piss, shit, vomit, or squirt all over the depot floor for all P.D. cared.

But no one came.

When P.D. looked back, the Kid stood two inches away. And his eyes were the gray, empty sockets of a skull.

P.D. cried out and stumbled again, falling onto his ass this time, feet over his head. The lantern flew out of his hand and landed near the dead house, where it shattered and burst into flame. P.D. crawfished backward through the dust. The Kid moved with him, arms slack.

P.D. screamed, clutching the reeking clothes like a shield.

The Kid stared straight ahead. He might have been looking into hell.

The broken lantern’s fire flickered and ebbed. Shadows stretched across the grounds and onto the platform, where they danced up the depot walls like the furtive movements of desert creatures. A wedge of light spilled from the main building’s door. But the Kid cast no shadow. His feet hovered an inch above the dust.

P.D. Thornapple opened his mouth to scream again. And then the Kid slapped leather, drawing both pistols and firing.

Slugs drove into P.D.’s belly. He flopped backward through the dust, the garments flying from his hands and landing in the fire behind him. The moon, a waxing crescent, grinned at him. His guts burned. He groaned and tried to sit up, but he had no strength. He coughed and spat a mouthful of bright blood into the dust. With arms made of lead, he searched his abdomen for bullet holes.

He found nothing.

The Kid floated closer, watching P.D. with those empty holes where his eyes should have been.

Pain blotted out all conscious thought. Darkness closed in. When he tried to speak, blood erupted from his mouth, some pattering onto his face, the rest raining around him. He turned his head and spat.

What’d you do that for? he whispered. I didn’t kill you.

But the Kid had vanished. The fire began to die out, and the rest of P.D.’s strength went with it. His head fell back to the earth, and he lay staring at the glimmering stars. They were cold and far away, like the eyes of dead gods.