Читать книгу Secrets of Northern Shaolin Kung-fu - Brian Klingborg - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

This book is a guide to the theory and practice of the traditional Chinese arts known collectively in the west as kung fu. Our specific topic is the kung fu style Northern Shaolin1, but much of the history, techniques, and concepts described herein relate to the martial arts as a whole. Hence, regardless of your preferred martial arts style and whether your interest lies in the historical and theoretical aspects of kung fu or purely in its practicality as a form of self defense, we are confident you will find something of value in the following pages.

Bookstores are now filled to overflowing with martial arts manuals. Some of the more popular Chinese styles about which numerous books have been written include Wing Chun, Tai Ch’i Ch’uan, and Hung-gar. Yet, while one or two books on various aspects of Northern Shaolin have already appeared in print, to our knowledge this manuscript represents the first attempt to comprehensively explain the history, development, and fundamentals of Northern Shaolin, and to place it within its proper context among the pantheon of the Chinese martial arts.

Currently, a vast number of modern schools claim to teach Northern Shaolin, but what they are in fact offering is a stew of various martial arts which may or may not have originated in Northern China or even within the Shaolin temple organization. Genuine Northern Shaolin is a distinct and discrete style with a very specific curriculum. This curriculum will vary from instructor to instructor and may feature a variety of auxiliary forms, but for it to be classified as Northern Shaolin it must include the following ten core forms: Open the Gate, Lead the Way, Astride the Horse, Pierce the Heart, Martial Technique, Short-Distance Fighting, Plum Blossom Moves, Leaping Strides, Linked Moves, and Skilled Method.2

In the context of the Chinese arts, Pek Sil Lum is classified as a northern and an external system. All arts that originated north of the Yangtze River are considered northern, examples of which include Shaolin Lohan, Hsing-I, Northern Praying Mantis, and Pa Kua. Those arts from south of the Yangtze, such as Hung-gar, Wing Chun, and Choy Lay Fut, fall under the category of southern styles. A common perception is that southern Chinese styles emphasize low, solid stances and focus on a variety of upper-body and hand techniques, while northern styles are characterized by higher stances and a diversity of kicking skills.

An external style such as Pek Sil Lum is one that relies primarily on strong, forceful techniques requiring a great deal of muscular power. In contrast, an internal style focuses on developing ch’i, an important concept to which we will return in a later section of this book. Ch’i is said to surpass muscular power in its ability to heal, harm, and protect one’s body. In reality, however, the division between internal and external is largely exaggerated. It is true that in the beginning stages the Pek Sil Lum practitioner concentrates on learning techniques that require a great deal of endurance, flexibility, coordination, and power. Yet as the practitioner progresses to the more advanced stages, he or she will learn to cultivate and use ch’i.

Pek Sil Lum is especially renowned for its huge repertoire of kicking techniques. These range from simple front kicks to jumping twirling crescent kicks and the impressive tornado kick, which will be featured in a later section of this book. Yet even though Pek Sil Lum has its roots north of the Yangtze River, it does not neglect upper-body techniques. In fact, the ten core forms include a wide assortment of open- and closed-hand strikes, as well as a plethora of hidden seizing and joint-locking maneuvers.

In addition to the ten core forms, the Pek Sil Lum curriculum features a two-person empty-hand sparring form and a number of weapon forms. Weapons taught include the staff, spear, saber, and broadsword, as well as the more exotic double sabers, double-hook swords, nine-section chain whip, three-section staff, long-handled knife, halberd, and various other classical Chinese instruments of war. While some may question the practicality of learning to wield such archaic weapons, the basic skills mastered through this kind of training can easily be applied in the real world. In the hands of a weapons-savvy martial artist, everyday objects such as stools, towels, chains, keys, pens, and so on can become deadly.

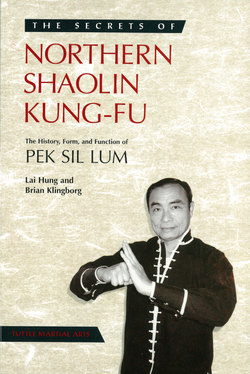

The expertise and inspiration for this book are provided by a Pek Sil Lum and Choy Lay Fut expert who has lived and learned the martial arts for an incredible fifty-two years—Sifu Lai Hung (Fig. 1). I first met Lai Hung in 1989 when I joined the UC Davis Kung-fu Club, where he taught the traditional way, with lots of sweat, a little blood, and a great deal of fun. At first sight, Lai Hung scarcely looked like the fierce fighter he was reputed to be—he stood no more than five feet eight inches tall, was of slight build, and, if not groaning over the form of some hapless student, usually displayed a friendly, relaxed smile.

Before taking up Pek Sil Lum with Lai Hung, I had tried my hand at other martial art styles, but I found the ritualized formality of training in many of these schools somewhat overbearing. With Lai Hung I discovered the joy inherent in studying the martial arts. When Lai Hung demonstrates one of the complicated Pek Sil Lum maneuvers, he frequently laughs with childlike glee as he leaps into the air to deliver a jumping kick or spins on the ground to apply a leg sweep. Although the martial arts are a deadly serious endeavor, under Lai Hung’s tutelage they are also an exhilarating form of recreation and enjoyment.

Lai Hung and I conceived this book with a dual purpose in mind: first, to provide a basic course of instruction in the fundamental techniques of traditional Pek Sil Lum; and second, to furnish the reader with a factual and sensible overview of the Chinese martial arts as a whole.

The instructional portion of this book introduces skills that every aspiring martial artist must master, including stances, footwork, kicks, and hand techniques. Once this essential groundwork has been established, the reader will learn an exercise routine that, over time, will both hone these basic skills and condition the body. Our course of instruction will culminate in the presentation of an authentic Shaolin form called tuan ta (short-distance fighting). Tuan ta is the most fundamental of the Pek Sil Lum core forms and it teaches basic skills such as striking, blocking, sweeping, grappling, kicking, and how to fight several opponents at once. To our knowledge, tuan ta has never before been made accessible to the general public. The final chapter offers photographic depictions and examples of the practical applications of this form.

In addition to illustrating the purely physical aspects of Pek Sil Lum, the following pages are intended to dispel a few popularly held misconceptions regarding the Chinese fighting systems. We feel this task is especially important because nowadays the vast majority of material concerning the martial arts—Chinese and otherwise—that appears in print, on television, in the cinema, or even in new forms of media such as the Internet consists mainly of hyperbole, hearsay, and nonsense. We are hopeful that our attempts here will encourage a more balanced view of the myriad Chinese martial styles, which are truly so extraordinary that they require no additional embellishment.