Читать книгу Secrets of Northern Shaolin Kung-fu - Brian Klingborg - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHISTORY AND OVERVIEW

Chapter 1

What Is Kung-fu?

In the West, we are accustomed to using the term kung-fu when referring to any Chinese martial art, no matter what the specific style may be. It will surprise some readers to learn, however, that kung-fu is not a synonym for “the Chinese martial arts.” Among modern-day Chinese practitioners, these disciplines are known as kuo shu, wu shu, wu kung, and a variety of other appellations-but only rarely as kung-fu.

A literal translation of kung-fu is “the effort and time it takes to accomplish a task or master a skill.” Another suitable translation might be “perfection achieved through exertion.” In other words, kung-fu is not in itself a skill—such as proficiency in the martial arts—but is rather the process of labor and practice through which a skill or ability is developed. Over the years, kung-fu has become synonymous with the Chinese martial arts because tradition maintains that it requires at least a decade of devoted effort to master any of the Chinese martial styles.

The technically correct term to use when referring to a fighting system is wu shu. Translated directly from the Chinese, wu means “military, warlike,” and shu denotes a “skill or method of doing something.” Although wu shu more precisely embodies the meaning of “martial art,” the use of kung-fu in this sense is so popular and widespread that the two terms have essentially become interchangeable.

Although history has supposedly witnessed the creation of over 1,500 wu shu styles, only about 150 of these have survived to the present day. While certain basic similarities exist among the various styles, in many respects they are profoundly different from one another. The advantage to this diversity is that a prospective martial artist is able to choose the style that best suits his or her interests and abilities. Currently, some of the more commonly taught styles include Hung-gar, Wing Chun, praying mantis, Choy Lay Fut, White Crane, and t’ai ch’i ch’uan.

Neither kung-fu nor wu shu as described above should be confused with the official wu shu that is practiced in the People’s Republic of China. PRC wu shu is primarily a performance art rather than a fighting system. It originated several decades ago when PRC officials realized the value of the Chinese martial arts as a cultural promotional tool. For political reasons, however, many of the more practical fighting techniques were removed from the traditional styles and what remained was blended with folk dance, Chinese opera, and acrobatics. While this form of wu shu is less martial than the more combat-oriented styles, it is nevertheless kung-fu of the highest order.

Chapter 2

A Brief History of the Chinese Martial Arts

Popular legends trace the origin of the Chinese martial arts to an Indian I monk named Bodhidharma. It is said that Bodhidharma was born into India’s noble warrior class, the Kshatriya, but that early in life he renounced his worldly position and became a disciple of Mahayana Buddhism. Around A.D. 520, Bodhidharma left India and made his way to China. He was initially warmly received by Emperor Wu-ti, but a dispute with the emperor over Buddhist doctrine eventually compelled him to seek refuge in the Shaolin temple in Honan Province. At the time of his arrival at the temple, the monks who lived there were absorbed in a scholarly exploration of Buddhism. Bodhidharma strongly believed that Buddhism was a philosophy to be experienced, not just read about in musty old books. Rather than participate in such a pedantic community, Bodhidharma took up residence in a nearby cave and spent the following nine years meditating in complete solitude. In time, the Shaolin monks came to refer to him as the “Wall-gazing Brahmin.” Eventually, Bodhidharma’s dedication and self-discipline impressed the monks and they invited him to share his knowledge. Bodhidharma set out to instruct the monks in his rigorous meditation techniques, which he believed were the key to Buddhist enlightenment. He soon discovered that poor health prevented the monks from meeting the physical challenges of his discipline. In response, he devised a series of exercises to strengthen their bodies and minds; these exercises were later set down in writing as the I-Chin Ching (Muscle Rehabilitation Classic). These exercises, passed down and modified by generations of Shaolin monks, are believed by many to be the foundation from which the various Chinese kung-fu styles evolved.

While many elements of the above legend are undoubtedly based on fact, others are most likely apocryphal in nature. Historical evidence does testify to the existence of a Buddhist monk named Bodhidharma who introduced Ch’an Buddhism (Zen in Japanese) into China. In addition, sources indicate that Bodhidharma spent some years at the Shaolin temple, and that he eventually died there. It is impossible to determine, however, whether or not he really was the founding father of Chinese kung-fu. On the one hand, as a member of the Indian Kshatriya class, it is likely that he had received training in some form of Indian yoga or martial arts before his conversion to Buddhism. He may have shared these physical techniques with the Shaolin monks in the form of the I-Chin Ching. On the other hand, there is absolutely no concrete evidence to support the claim that Bodhidharma was the author of the I-Chin Ching, or that this work gave rise to the Chinese kung-fu styles.

Some scholars believe that basic martial arts techniques were first developed in India and later transported to China along with other elements of Indian culture. The previously mentioned Kshatriya class were known to have practiced some form of unarmed fighting as early as 1000 B.C.3 It is conceivable that, centuries before Bodhidharma’s lifetime, these skills were transmitted along trade routes into China, where they formed the basis for Chinese kung-fu.

The ancient Greeks also popularized a number of fighting styles, some of which made use of kicking, punching, and grappling techniques. Scholars have speculated that in the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquest of India in 326 B.C., these techniques were imported into India, and exported from India to China.4

Long before Alexander’s campaigns, however, the Chinese were practicing large-scale organized warfare. Numerous historical sources, such as Ssu Ma Ch’ien’s Records of the Historian, tell us of epic battles and martial derring-do dating back to the Chou dynasty (1122-221 B.C.). Judging from these accounts and the ancient arms and armor that have been unearthed by archaeologists, the Chinese were using relatively sophisticated combat techniques even during this early period.

Regardless of whether the inspiration for Chinese kung-fu came from Greece, India, or China itself, there is little doubt that the Shaolin temple evolved into the most influential martial arts center the world has ever known. According to legend, the Shaolin monks did not engage in any martial arts training prior to the arrival of Bodhidharma, but within a scant 150 years of his death they had already earned a reputation as formidable fighters. By A.D. 600, their fighting prowess was so renowned that the founder of the T’ang dynasty (A.D. 618-907) enlisted their support in his bid for the throne.

For a period of one thousand years, beginning with the T’ang dynasty, the Shaolin temple experienced a golden age. Living in relative peace and prosperity, the monks were free to pursue the twin disciplines of Buddhism and kung-fu. It was during this millennium that additional Shaolin temples were constructed, the most famous of which was the southern Shaolin temple, established in Fukien Province around A.D. 1399.

The Fukien temple was supposedly the site of the celebrated thirty-five chambers in which Shaolin disciples learned different Kung-fu techniques. This temple is also said to have featured a corridor containing eighteen wooden dummies, which served as a kind of graduation examination for students who had completed the training program. In order to qualify as a kung-fu master, acolytes had to pass through this corridor without being injured or killed by the mechanically operated dummies. According to legend, those who made it all the way through faced one final challenge: Using only their forearms, they had to lift and carry a heavy iron urn filled with hot coals. One side of the urn featured a relief of a dragon, while the other was inscribed with a tiger. If the acolyte succeeded in lifting the urn, the dragon and tiger emblems were branded onto his forearms, forever marking him as a Shaolin master.

The invasion of the Manchus and the subsequent founding of the Ch’ing dynasty (A.D. 1644-1911) signaled the decline of the Shaolin temple organization. The Manchus, as foreign invaders attempting to assert control over a vast territory of hostile natives, made it a priority to eliminate all possible sources of resistance. They naturally regarded with great suspicion the famous fighting monks of the Shaolin temple organization. In 1736, the Ch’ing emperor ordered an attack on the Fukien Shaolin temple. With the assistance of a traitorous monk, the temple was destroyed and many of the monks killed.

While Ch’ing harassment was undoubtedly unpleasant for the Shaolin monks, in a strange way it ultimately proved beneficial to the growth of the Chinese martial arts. Prior to the Ch’ing dynasty, the practice of Chinese kung-fu was largely restricted to disciples of the Shaolin temple organization. With the destruction of the Fukien temple, however, a number of Shaolin monks fled into the countryside, where, for the first time, they began to teach their arts to ordinary people. Throughout the remainder of the Ch’ing dynasty, Shaolin kung-fu continued to spread outside the confines of the temple walls. In this manner, just as a forest fire sparks the growth of new trees, the persecution of the Shaolin temple organization was the catalyst for the dissemination and renewed growth of Chinese kung-fu during the nineteenth century.

In the waning years of the Ch’ing dynasty, the Shaolin temples were allowed to resume activity without interference, but their importance as the center of Chinese kung-fu continued to diminish into the early years of the twentieth century. In 1911, the imperial government was overthrown, and the country was subsequently divided into territories controlled by various local warlords. Eventually, the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek embarked upon a campaign to strip the warlords of their power and reunify the country under central leadership. This campaign proved to be the final undoing for the Shaolin temple in Honan Province.

In 1927, Chiang dispatched General Feng Yu-hsiang to Honan Province to fight the warlord Fan Chung-hsiu. It so happened that the abbot of the Shaolin temple, Miao Hsing, was a good friend of Warlord Fan. General Feng soon rousted Fan in battle, forcing the latter to take refuge in the Shaolin temple. When Feng arrived to capture Fan, Miao Hsing ordered his monks to attack the government troops in a bid to save the vanquished warlord. In the ensuing skirmish the monks were no match for the guns of Feng’s soldiers and many were killed, including Miao Hsing. After the battle, Feng ordered the temple burned to the ground.5

Although this was the final straw for the Shaolin temple organization, the study and practice of Chinese kung-fu continued to flourish in the countryside. It was during this period that a number of lay organizations dedicated to the martial arts were founded. The first of these, the Ching Wu Association, was established in Shanghai in 1909.

In 1927, the newly restored Republican government created the Central Kuo Shu Institute in Nanking to consolidate, organize, and promote Chinese kung-fu. The institute brought together five famous martial artists, known to posterity as the Five Tigers of Northern China. One of the Five Northern Tigers was the Pek Sil Lum and ch’i kung expert Ku Ju-chang, whose student Lung Tze-hsiang was later to become Lai Hung’s Pek Sil Lum instructor.

A few years later, the Five Northern Tigers went to Canton and established a second institute along with a group of renowned masters known as the Five Tigers of Southern China. One of the Five Southern Tigers was a Choy Lay Fut expert named T’an San, whose pupil Li Ch’ou was later to become Lai Hung’s Choy Lay Fut instructor.

In 1937, the Japanese invaded China and the nation spent the next eight years at war. Later, as World War II drew to a close, the Chinese became embroiled in a civil war between the Nationalist government and Communist insurgents. After the Chinese Communists ascended to power in 1949, Chinese kung-fu came to be regarded as an unpleasant relic of the past. Many Chinese martial artists eventually emigrated to Hong Kong, Singapore, and other parts of the world, where they could continue to practice their arts without interference. And so this tradition lives on today.

There is a curious footnote to the story of the Shaolin temple organization. During the kung-fu craze that swept the world in the 1970s and again in the early 1980s, a number of movies featuring heroic Shaolin monks were filmed. Before long, kung-fu fans around the world came to regard the Shaolin temple organization as the ultimate martial arts academy. When China eventually opened its gates to tourism, visitors clamored to see the Honan temple. Unfortunately, by this time the temple had fallen into a state of great disrepair. The Chinese government soon recognized that the temple represented a potential tourist gold mine, and initiated a program to have it refurbished. While there is currently some debate over whether the monks now inhabiting the Shaolin temple in Honan are truly Shaolin disciples or simply kung-fu performers capitalizing on the tourist industry, it is now possible for anyone to pay for instruction at this historic site!

Chapter 3

The Origin of Pek Sil Lum

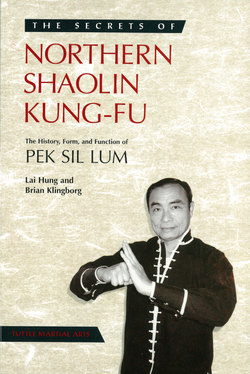

The roots of Pek Sil Lum are obscure and open to debate. No one knows I for sure when the system originated, what styles influenced it, or who exactly was responsible for developing its ten primary forms. Yet without exception, all legitimate Pek Sil Lum instructors today trace their lineage back to one of the twentieth century’s most celebrated martial artists: Ku Ju-chang (Fig. 1).

Ku Ju-chang was born in Chiangsu Province around 1894. His father, Ku Lei-chi, owned a business that provided armed escorts for merchants and rich civilians traveling through the bandit-infested roads leading to and from Nanking. Ku Lei-chi apparently had a connection to the Honan Shaolin temple and was himself an accomplished practitioner of the martial art style known as t’an t’ui, which originated within China’s small Muslim community. The elder Ku died when Ju-chang was about fourteen years old, but before passing away, he told his son to seek out a Shaolin monk named Yen Chi-wen, who was at that time living in Shantung Province. Two years later, at the age of sixteen, Ku Ju-chang left home to begin his studies with Yen Chi-wen. By most accounts, Ju-chang studied with Yen Chi-wen for eleven years, mastering various Shaolin temple styles. Whether the ten primary forms of Pek Sil Lum were passed on to Ku Ju-chang directly from Yen Chi-wen is impossible to say. It does seem likely, however, that Yen Chi-wen taught Ku Ju-chang the iron palm and ch’i kung techniques that later made him famous throughout China.

Ku Ju-chang had already attained some fame by the late 1920s, when he participated in a martial arts competition sponsored by the National government and the martial arts community. He is said to have finished among the top ten in this competition, which was, by most accounts, the largest and most prestigious ever witnessed in China up to that point. Around the time of this competition, the Nanking Central Kuo Shu Institute was founded, and Ku Ju-chang was invited to serve as one of its martial arts instructors. The institute succeeded in bringing together the preeminent martial artists of the day, known as the Five Tigers of Northern China. This select group included Ku Ju-chang, Wan Lai-sheng, Fu Chen-sung, and Li Hsien-wu. Aspiring martial artists flocked to the institute to take advantage of the opportunity to study with these renowned masters.

A year or so later, these five patriarchs went to Kwangtung Province to assist in the organization of a second Kuo Shu Institute in Kwangchou. There, they were joined in their endeavors by a group of famous martial artists known as the Five Southern Tigers, most notably among them a Choy Lay Fut practitioner named T’an San (Fig. 2). Ku Ju-chang opened a school not far from T’an San’s academy, and these two eventually came to openly exchange both knowledge and students. It seems likely that both T’an San and Ku Ju-chang incorporated techniques learned from the other into their respective styles, perhaps modifying them as a result.

In addition to his exchange with T’an San, Ku Ju-chang is said to have studied a variety of other styles with famous masters, including hsing-i, pa kua, and Sun style t’ai ch’i with Sun Lu T’ang, Wutang sword style with Li Ching-lin, and ch’a fist with Yu Chen-sheng. History, however, best remembers Ku Ju-chang for his iron palm and ch’i kung abilities. Examples of his skill include breaking thirteen stacked bricks with a single silent slap, allowing a car to be parked on his stomach, and so on (Figs. 3 and 4). The most famous story regarding his prowess is supposed to have occurred in 1931. As legend has it, a circus from a foreign land arrived in Kwangchou with a wild horse as its star attraction. The circus promoter (often said to be a Russian) offered a reward to anyone who could tame the horse. Apparently a number of martial artists tried to subdue the horse and were kicked or trampled. Eventually, however, Ku Ju-chang stepped up and slapped the horse once on the back. The unfortunate beast died soon after and an autopsy revealed that its internal organs had been severely damaged. This is doubtless a highly romanticized version of what actually happened.

A perhaps more accurate version of the story is that Ku Ju-chang visited the circus with some of his students and asked to see the horse. When the circus promoter realized that Ku Ju-chang was one of China’s premier martial artists, he immediately apologized for issuing the challenge and retracted it on the spot. He then took Ku Ju-chang to see the animal. Ku Ju-chang ran his hands across the horse’s back and under its belly, commented on the smoothness of its coat, and left without further incident. Several days later a rumor erupted that the horse died soon after of internal bleeding, as a direct result of Ku Ju-chang’s iron palm technique.

Ku Ju-chang survived both the Japanese invasion of China and the turmoil that was to follow. He continued to teach Pek Sil Lum until he died in his mid-sixties. He was survived by several students, one of whom was Lung Tze-hsiang. When the Chinese Communists assumed power on the mainland in 1949, Lung Tze-hsiang moved to Hong Kong, where he later taught Lai Hung.

It should be noted that many teachers nowadays use Pek Sil Lum as a general term to denote the melange of styles and techniques that emerged from the interaction of the Five Northern and Five Southern Tigers during this watershed period in the history of Chinese martial arts. In addition, there is another branch of Pek Sil Lum that was transmitted through Yen Shang-wu, who, along with Lung Tze-hsiang, studied under Ku Ju-chang; this style differs slightly from the one presented here, but, we wish to emphasize, it is by no means less valid or “traditional” (Fig. 5). As a result, there is currently some variation between the Pek Sil Lum taught from one school to the next. Suffice to say, however, if the school’s lineage extends directly back to Ku Ju-chang and features the ten core forms, it is part of the Pek Sil Lum family.

Chapter 4

Sifu Lai Hung

Lai Hung (Fig. 1) was born into troubled times in a troubled country—the year was 1938 and the place was China. At the time of Lai Hung’s birth, China had been mired in a desperate struggle against the invading Japanese army for just over thirteen months. In that brief period, the well-equipped and modernized Japanese forces had stormed Beijing, smashed through heavy resistance in Shanghai, and laid waste to Nanking, forcing the Chinese government to beat a hasty retreat to the remote province of Szechwan. The effect of these hostilities on ordinary Chinese citizens was severe—food and other necessities were scarce and violent death was an everyday occurrence.

China’s war of attrition against Japan lasted until August 14, 1945, when, in the wake of the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, the Japanese emperor ordered his nation’s forces to lay down their arms. But China’s troubles did not end along with the Sino-Japanese War. Immediately after the Japanese surrender and withdrawal from Chinese soil, a civil war broke out between the Nationalist forces under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communists under Mao Tze-tung. This internal struggle raged on for another four years, exacerbating the already intolerable conditions in China.

The hardships faced by the young Lai Hung, who until the age of ten had never known a life in which there was not war and suffering to be endured, no doubt influenced certain aspects of his character. These character traits, shared by many through history who spent their formative years in a similarly harsh environment, included persistence in the face of adversity, determination, self-discipline, and an ability to withstand pain, hunger, and discomfort. Interestingly enough, it is perhaps precisely those traits, born out of the adversity he faced early in his life, that made possible Lai Hung’s later achievements in the martial arts arena.

Lai Hung’s father worked as a bodyguard and was an avid student of the Chinese martial arts. Having lived through periods of great turmoil himself, the elder Lai believed in the necessity of knowing how to defend oneself. Soon after Lai Hung’s eighth birthday, his father arranged for him to commence his martial arts training with a famous master named Lee Nam. Sifu Lee taught a practical and powerful style not unlike Choy Lay Fut known as hung t’ou fo wei. Around this time, Lai Hung also received instruction from two other well-known teachers, one of whom was nicknamed “Master Iron Palm” and the other “the Iron-Headed Mouse.”

In 1949, the Lai family emigrated to Hong Kong, where both Lai Hung and his father found work at a shoe manufacturing company. Soon thereafter, Lai Hung sought instruction from the famous teacher Lung Tze-hsiang (Fig. 2). Lung was one of a few senior students who were recognized as legitimate successors to Ku Ju-chang. At the time, the Hong Kong Athletic Association served as an informal headquarters for martial arts instruction and training in Hong Kong, and Sifu Lung’s classes were held there. Under Sifu Lung’s guidance, Lai Hung embarked upon his study of traditional Pek Sil Lum, classical Chinese weapons, Yang-style t’ai ch’i ch’uan, and various forms of ch’i kung.

Initially, Lai Hung’s mother objected to his martial pursuits. Years of poverty and food shortages had left Lai Hung skinny and frail, so naturally his mother was concerned that his training would lead to injury. But within a few months of joining Sifu Lung’s class, she noticed dramatic improvements in his posture and overall health. From that time on, she fully encouraged his desire to learn Chinese kung-fu.

In the period immediately following World War II, Hong Kong emerged as a fertile environment for the continued development and expansion of the Chinese martial arts. This was primarily due to the fact that dozens of famous masters from all over China fled to the island territory when the Communists assumed power on the mainland. Young students like Lai Hung benefited enormously from this chain of events. For the first time in history, accomplished practitioners of every conceivable style found themselves living together in a very small, interdependent community. Although this situation produced plenty of conflicts, it also resulted in an unprecedented degree of collaboration between these martial arts patriarchs. As a result, Lai Hung and his fellow pupils enjoyed an unusual amount of interaction with a variety of instructors.

When Lai Hung was seventeen, a famous Choy Lay Fut practitioner by the name of Li Ch’ou was invited to participate in Sifu Lung’s classes. Li Ch’ou and Lung Tze-hsiang were actually brothers in the kung-fu lineage—Li Ch’ou was a disciple of T’an San, and in the years when T’an San and Ku Ju-chang were exchanging students, Lung Tze-hsiang had also studied Choy Lay Fut under T’an San. Lai Hung eagerly took advantage of the opportunity to learn this relatively new martial arts style. He soon discovered that he enjoyed the direct simplicity and forcefulness of Choy Lay Fut. Lai Hung continued to study with Li Ch’ou for the next eight years.

Lai Hung’s first major martial arts competition was the Hong Kong-Macao-Taiwan tournament held in Taiwan in 1957. At the time, the custom was for Hong Kong’s preeminent martial artists, known as the Ten Tigers of Kwangtung,6 to each select their best students and have them all compete against one another for the honor of participating in important tournaments. Sifu Lung nominated Lai Hung without even bothering to inform the latter of his decision. Lai Hung didn’t learn that he was to compete until a few days later, when a group of newspaper reporters showed up at the Athletic Association to interview him.

Lai Hung was unsure of how his father would react to this news, so he kept it a secret. Needless to say, when his father opened up the morning paper several days later and discovered his son’s picture and a story on his participation in the upcoming tournament, he was very angry. The elder Lai was concerned that his son would either be injured or would fight badly and cause a loss of face for the family. He initially refused to allow Lai Hung to take part in the competition, but after Sifu Lung invited him to tea and explained the situation, he grudgingly gave his consent. The elder Lai, however, was not content to leave anything to chance, and so he arranged for an old Choy Lay Fut master named Ch’en Chen to come to his house every evening to provide special training for Lai Hung.