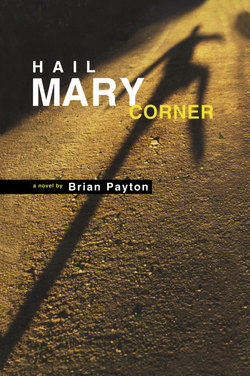

Читать книгу Hail Mary Corner - Brian Payton - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE DEDICATION September 1982

ОглавлениеMy knees were out of shape. It happened every summer. You spent all your time swimming, biking, lounging in the grass, and the callus that built up over the school year quickly wasted away. It was only when you came back in September that you remembered kneeling was supposed to be painful.

The new abbey church was filled with the soaring angelic polyphony of the seminarians and the haunting chant of the monks—Allegri’s Miserere mei. Bowing my head and closing my eyes, I felt the presence of God. I could also feel the warmth of Jon kneeling next to me: a familiar whiff of soap and evaporating Aqua Velva.

When I opened my eyes, I saw the greasy scalps of seminarians gently bobbing in front of me, and black monks displayed in neat rows in the oak stalls to the left. Across from us in the north transept sat a cardinal and three bishops in pointy mitres, plus a pair of short Orthodox abbots with nearly identical salt-and-pepper beards. On the right a capacity crowd of regular priests, nuns, and laypeople filled the nave to overflowing. In the centre stood a massive granite altar under the curve of a dome sixty feet in the air. Late-morning sunlight streamed through stained glass, bathing the pallbearers in red, orange, and yellow as they entered the aisle in the middle of the faithful.

Four seminarians from the senior class carried a small box atop a wooden litter draped in a shawl of white with a gold cross on top. Stiff and serious, they stopped at the foot of the altar where the abbot and four monks in gold-brocade vestments waited with the cardinal, who tipped his crosier—the hooked staff of the Shepherd of Men—in solemn consent. With wizened hands the monks reached out and took the box from the boys, nodded a blessing to them, then placed it carefully under the altar.

The box contained the relics of Saint Scholastica, patroness of rain. She was invoked against childhood convulsions. Her greatest claim to fame, however, was the fact that she was the twin sister of Saint Benedict. Under every altar there should be buried some holy thing: blobs of dried blood, hair, body parts, or personal effects. In this case, we were told, it was bones. I closed my eyes again and wondered what kind of bones were in that little box. Jaw? Teeth? Skull cap? Probably her knees, I thought, feeling my own go numb.

I was late again this year, my third at the Seminary of Saint John the Divine. I had arrived just in time to jump out of my shorts and into wool pants and a navy blazer—our school uniform. The organ called out to me as I frantically changed, alone, all the way up in the juniors’ dorm. I tied my tie as I ran to the ceremony, the familiar clomp of last year’s shoes echoing through the hall.

The monks had been waiting for this “D-Day” since long before we were born. A model of the planned church had been gathering dust in the guesthouse lobby since 1957. What they ended up with looked completely different.

The new abbey church was a sprawling concrete edifice with a pointed dome. It had dozens of tall, abstract, stained-glass windows, a rainbow of cough drops melted together. From the outside it appeared as if a giant spaceship had landed from some postmodern Catholic galaxy. It took three and a half years to build—a good part of it with seminarian slave labour—and like the great churches of old, it would probably never really be finished. Father Ezekiel, our ancient, liver-spotted science teacher, said the new structure would stand at least until 2482, barring nuclear attack.

As the Miserere faded, the cardinal called for the Holy Spirit. “Come down and bless this place,” he said. “Make it a sanctuary dedicated to the worship of God from this day forward.” I closed my eyes again and imagined the Holy Spirit descending from the popcorn clouds, through the flatulent stench of the pulp-mill town. He’d see the church, the monastery, and the seminary lined up along the cliff—the bell tower like a beacon leading him in. He’d pass through the thick concrete dome and hover over the altar where the cardinal and monks raised the Blessed Sacrament to the sky. He’d breathe in the rich incense and know he was home. I opened my eyes. There was no sign of the Holy Spirit. Instead, when the organ fell silent and the cardinal stopped mumbling, we all heard a sound very much of this world.

Every head turned to the back of the church where a huge baptismal font bubbled holy water over granite rocks and into a little pool. The cardinal paused a moment more to make sure of what he heard. Crock, crock echoed again, announcing the fact that an amphibian had taken up residence in God’s newest house. The place erupted in applause.

“It sounds as if all the earth is celebrating today,” the cardinal said. “All God’s creatures are raising their voices in praise.”

When I was a child, I wanted to be a priest. I wanted to be the lightning rod for all that limitless spiritual power. I would walk down the street knowing that the saints and angels were backing me up and that I was doing the most important thing in this world: God’s Work. That was, after all, why we were here. And so I left home for the seminary.

Perched high above Vancouver Island’s broad Ennis Valley, the Seminary of Saint John the Divine was a boarding school with a specific agenda: to help young men find their Calling and to aid in their Priestly Formation. Everyone, right down to the scrawniest, snot-nosed freshman, had to give a rating of his potential religious vocation on a scale of one to ten. “One” meant you were probably an atheist and “ten” signalled candidacy for canonization. It happened at the beginning of each term. I always rated myself a respectable “six”—high enough to show a spiritual pulse but low enough to avoid any undue attention. But as time went by and increasing doses of testosterone pulsed through my veins, it was becoming abundantly clear I wasn’t cut out for the job.

Saint John the Divine was run by monks; Benedictines to be exact. Their kind had been living the Rule of Saint Benedict since anno domini 529. Their wardrobe consisted of identical black-hooded habits. They eschewed vanities like deodorant and toothpaste—baking soda was good enough. Shampoo was for women.

Until I actually came across one I had a storybook idea of monks. Friar Tuck and the Grim Reaper instantly sprang to mind. The first one I ever encountered was Brother Thomas. A tall, skeletal man slightly older than my father, he had a permanent squint as if he’d been sucking a lemon or was thinking so hard he was about to burst a blood vessel.

“Man of God!” he declared that very first day as he surveyed my Rocky III T-shirt and tight blue jeans. I hadn’t even made it into the building. The earphones attached to a poorly concealed Walkman were of particular interest. Carefully he removed them from my head and listened to Billy Idol for a moment before issuing his signature grimace. He told me to change out of my “getup,” then store it and the offending machine in my trunk. “Be on time and in uniform for the Reading of the Rules,” he added. “There the Veil of Misunderstanding will surely be lifted.”

This morning, this Dedication Day, Brother Thomas stood unnaturally erect in front of his stall “conducting” the schola, his hand undulating like a belly dancer’s over his Latin graduale. No one paid him any attention.

Father Albert was my second monk. He was a plump, rose-cheeked man of considerable style and charm. After my name and where I was from, the next thing he wanted to know about me was the last movie I’d seen. Addicted to films, Father Albert confessed he hadn’t been out to a theatre since Doctor Zhivago. He survived on videos and detailed accounts of recent movies from his students. I was to tell him all about Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan.

Today, for this momentous occasion, Father Albert was seated at the helm of his new pipe organ, eyes closed, arms outstretched, head thrown back in ecstasy.

“Amplius lava me ab iniquitate mea, et a peccato meo munda me” we sang. Wash me clean of my guilt, purify me from my sin.

On the way back from Communion I stopped to take it all in. I nearly tripped looking up at the distant honeycombed ceiling, then followed Jon into our pew where we knelt and made the sign of the cross in perfect unison. As I watched Father Albert sweat and sway toward a musical crescendo, the Eucharist attached itself firmly to the roof of my mouth. I held it there with my tongue until it dissolved like an M&M and became part of me, body and soul.

As I prayed, I thought about my grandfather. He had died that summer, and every day since I had been variously haunted or comforted by the knowledge that he was now omniscient, gazing down from heaven, watching my every move. He saw me here, kneeling at the dedication of the new abbey church, and he was proud. But he also saw me when I was naked, playing with myself in the shower before I left on the bus for the seminary. I was nearly paralyzed with guilt after that, knowing in my heart that he saw what these hands, these same hands that were pressed together in prayer, had been doing only two days before.

So, I prayed to my grandfather, now you know the truth.

During that endless Mass, I had time for a revelation. If my grandfather was in heaven, how could he be upset or disappointed? Wasn’t he shielded from all things unpleasant in the radiant face of God? It seemed a terrible fate to have to watch people for eternity picking their noses, stealing, and doing and thinking all the other things they did and thought in private. This led me to wonder about the saints, the angels, and even God Himself: all of them watching us fall and beg forgiveness, fall and beg again. Down here we only had full knowledge of our private lives. We only truly knew our sinful selves. I thought what an unbearable burden it must be to know the sins and secrets of all the world, especially the ones you loved.

The afternoon sunlight pushed down on Saint John the Divine like a hand on the back of a neck. But with the blue-sky backdrop and green junipers out front the place looked like a postcard from somewhere a whole lot better than this.

Although it was Monday, we had the day off. The monks had another big Mass with the remaining bishops, abbots, and assorted Catholic wheels. The party atmosphere died down right after lunch as the guests finally left the monks and student body to settle into their new/old routines.

Saint John’s was a simple three-story structure of bare grey cinder blocks and big picture windows. A terra-cotta roof flattered it with the look of an old California mission. The seminary wing was connected to the monastery by way of the scullery, dining halls, and guesthouse. The gentle side of the hill rolled down from the buildings and the new abbey church in a quilt of sun-bleached grass, lush clover, and dandelions past their prime. It came to an indeterminate end at a small body of water at the edge of the woods and the foot of Mount Saint John.

The monks preferred us to call it Mary Lake, but that would be overly kind. About fifty yards across and only eight feet deep in the middle, it was semi-square, betraying its man-made origins. The pond attracted boys, frogs, and flies and exuded a fetid stink during the warmest months. Its ill-defined banks were slick with mud, and it was difficult to tell where land ended and water began. To the student body it had always been and would forever remain the Bog.

Dandelion seeds cartwheeled down the hill and brushed against my ankles. Cool clay oozed between my toes. Jon floated on his back, arms splayed, fingers moving enough to keep him afloat on the smooth, almost stagnant surface.

Although we had exchanged letters and the odd phone call, we’d gone nearly three months without seeing each other and, to me, that seemed like forever. I wondered if he felt the same.

Jon had changed since I’d last seen him. His face was slightly more angular than before, jaw more pronounced. His shoulders appeared wider. Over the summer he had even grown a few curly black hairs on his sternum. I glanced down at my bare chest, then dived in, disturbing the calm. Staying under until my lungs burned, I resurfaced behind him. “Miss me?” I asked.

He lied and said he didn’t, then silently slipped away, tea-coloured skin flowing easily under the surface, the dark waves of his hair smoothed flat against his skull. He couldn’t stay under as long as I could. After coming up and gasping for breath, he rubbed his eyes and stared at the new abbey church. “What do you think about all that money going for a building like that? It’s not like any poor people will ever get the chance to use it.”

I swiped the hair from my eyes and blew my nose. “When you say stuff like that, it makes me think you’re reacting against your own cushy life. You wanna hang with the poor people? Come on over to my place for a while.”

Jon’s family owned Benning Home Furnishings: Quality & Tradition Since 1953. He always had a selection of new shoes and, other than his school uniform, he never wore the previous year’s clothes. On top of being rich, Jon had “class”—a kind of charm and refinement I was beginning to notice in others but found sorely lacking in myself.

Blessed with dark, deep eyes, Jon also had skin that was always a shade or two healthier than mine. When he smiled, people stopped what they were doing. From visiting sisters to the girls at the corner store, the few women who entered our lives were united in their opinion: hearts would be broken. Even my own mother said as much. Jon and I really didn’t look much alike—me being pale, my hair straight and blond—but sometimes when we were in town people would mistake us for brothers. That always made me proud.

Jon filled his mouth with Bog water and spat it at me in a thin stream through perfect white teeth. “I guess I did miss you.”

Relief flowed warmly inside me. We floated together, suspended in the last few moments of freedom. Tomorrow classes would start and the whole heavy, antique machinery of the place would shake and rumble to life, then hum all the way to Christmas.

An indistinguishable black form emerged from the guesthouse two hundred yards away. We both squinted, unable to determine who it was. But when the hands went up and rested on the hips, we knew we were regarding Father Albert. He stopped and watched us floating in the Bog, staring back at him. Looking left and right down the empty drive, he started marching across the field.

The first thing to come off was his scapular—over his head and onto the grass. Then came the belt. He picked up the pace and unbuttoned his habit, shrugging it off halfway to the Bog and continuing his waddling jog in T-shirt, boxers, black socks, and shoes. Jon and I turned to each other, bug-eyed with surprise, ready to laugh but not knowing where to begin. Then off came the shoes and socks and finally, at the edge of the mud, the extra-large T-shirt. Skin that white shouldn’t be exposed to the elements.

“You’re the man, Pair!” Jon cried, nearly climbing out of the water. “You are the man.”

When the other monks weren’t around, we called him Pair because père was French for father and he hated teaching French; because he was shaped like a pear; and because he did things no other monk would do.

“Watch out for the tsunami, boys.” He displaced a surprisingly small amount of water, then floated on his back, his taut, hairless gut breaching the surface like the head of a beluga. Treading water with unnatural ease, he murmured, “Isn’t it great when you wait for something, wait a really long time, and it turns out better than you imagined? Must be a little like heaven.” He rolled off his back and scanned the hill to ensure the coast was still clear, then gazed up past the trail of clothes to the new abbey church. “It’s not every day the world gets such a magnificent new sanctuary. I feel like a kid again.”

I sighed, then dog-paddled a figure eight around to the two of them. “It’s just a fancy room for a pipe organ.”

Father Albert’s eyes narrowed slightly, then shifted in my direction. As a satisfied smile stretched across his face, he blew bubbles in the Bog and laughed. “Pinch me. I must be dreaming.”

Night in the dorm. The juniors’ dorm now, not the nursery. The freshmen and sophomores were down the hall, crammed together in the biggest room on campus. Although it was more permanent and less crowded, the nursery reminded me of one of those gymnasium disaster relief centres you see on television with people flaked out all over the floor after an earthquake or flood. Even in the relatively posh juniors’ dorm we slept side by side, partitioned off by flimsy chin-level dividers. Privacy was for people with something to hide.

The bed cradled me hammocklike on old sagging springs. Breathing in bleach, sweat, and dust off the sheets and thin mattress, I could see the lump of Jon in the bed across from me, with Saint Charles Borromeo staring down from his frame on the wall above. Connor, the other guy in our bay, had nailed St. Chuck up there. Aside from being the patron of seminarians, the saint, like Connor, suffered from a debilitating stutter. I couldn’t see him clearly in the dark, halo radiating around his piously cocked head, but I was aware of his gaze. Then someone whimpered in his sleep and I began to pray.

Five days, Lord, and holding. Help me keep my promise to turn away from sin. Help me fight myself and never give up. Make me strong. Make me strong. Make me...

I listened to our breathing. We all seemed to fall into a pattern. Finally I drifted away on a stream of Hail Marys, travelling away from myself, away from what was into what would never be.