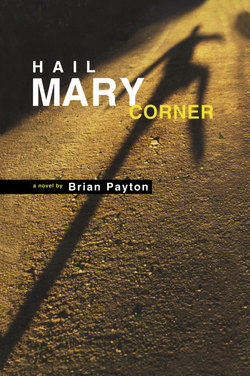

Читать книгу Hail Mary Corner - Brian Payton - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

TWO ROMANS AND CHRISTIANS

ОглавлениеThe close September evening gave no hint of the coming change of season. On its way down, the setting sun kissed the nipple of rock at the top of the large, full hill that was Mount Saint John. When the day finally slipped past the edge of the horizon, the last of the light pooled in the Bog in a blue-orange sheet like metal exposed to fire.

I wasn’t sure how they played it at other schools, but at the Seminary of Saint John the Divine, contestants concentrated on the apprehension, torture, and simulated martyrdom of Christians. Most boys wanted to be Roman.

Old foxholes were dug in the black forest soil. They had been there for generations, hidden behind bushes and under the fan of upturned trees. Everyone knew where they were, except the new kids. I stood alone inside one such crater, last year’s leaves rotting in a pool at my feet. It smelled like urine. I could hear hoots and hollers spread thin in the distance. Crouching down, I pulled out a Marlboro, tapped it on the crush-proof box, and lit it. Jon jumped in from out of nowhere and splashed some of the muck on my cheek.

“Scrupus,” I said, lighting the cigarette, then wiping my face.

“Nutrix,” Jon replied.

“Where’s Connor?” I asked.

“Dunno.”

“What’s the plan?” I took a long drag and tried to look like an army field officer discussing plans for an offensive.

“Eric’s a Christian,” Jon announced. “Volunteered again.”

“He’s so literal. He’ll go far.” There was a rustling of leaves and then choked laughter from behind a rotting log. We both heard it. I removed the cigarette, put a finger to my lips, and winked. “So maybe we’ll head back toward the gym,” I said just loud enough for them to hear.

“Yeah. We’ll surprise the little shits down there.”

Jon pulled my head close and whispered in my ear that he’d leave, making enough commotion for both of us. I should stay behind for the ambush. As soon as he heard me yell, he’d come flying back. I gave him a drag, pinched off the half-smoked butt, and replaced it in the deck. Jon disappeared into the quiet.

Half an hour earlier I had fished a folded little slip of paper with an R out of a baseball cap, which meant I got to hunt down passive apostles and bring them to justice. Roman justice. That should have been exciting, but I was getting a little too old for this kind of crap.

A few minutes later the new kids poked their noses over the rim of the foxhole and peered in. Fresh veal. I scrambled up the side of the hole, slipping and landing on my shin as they hopped away like deer. Jon saw them. He was waiting behind the trunk of an immense maple. We tore after them full-tilt.

Trunks whizzed by in the blue-black twilight. We were closing in. When they were almost to the edge of the Bog, one of them whined like a dog about to get whacked with a broom.

Jon already had his Christian subdued. In mid-stride I reached out just as my man turned around to see. I grabbed him by the collar and we both instantly tripped, tumbling over the mossy twigs into the tall grass. Quickly I jumped back up, hands in front of me ready to choke. The kid lay frozen on his face hoping that if he played dead long enough I might just sniff him, paw around, then wander back into the woods for some berries.

“Get up!” I ordered.

“I’m sorry,” he mumbled straight into the ground.

“Sorry for what? Getting caught? Now you’re going to die for your faith.” I took out the now-crumpled deck of smokes and lit one.

“Who are you?” he asked, slowly sitting up.

“Who am I?” I blew smoke down at him.

“You never came to the Reading of the Rules.”

“Who am I? That should be one of the first things you learn here.”

“Sorry.”

“Stop with the sorry routine. Get up.”

He stood. I couldn’t see him well, but he was a small kid with wide hips and narrow shoulders like those of a girl. His skin seemed pasty, his eyes were almond-shaped, and he had thin, serious lips. You couldn’t really tell if he was white or Mongolian or some wild mix of the two.

“The question,” I said, “is who the hell are you?”

“Michael Ashbury.”

He didn’t look like an Ashbury, that was for sure. I grabbed his collar again, blew a puff of smoke into his face, then shoved him toward the Coliseum. Jon was already leading his Christian down the Appian Way, and I was falling behind.

Mosquitoes filled the air. I almost breathed one in. The Bog churned them out like a factory. There were three flashlights among thirty seminarians. The others were still in hiding or pursuit, and we couldn’t wait any longer. Rosary was only fifteen minutes away.

Connor had a Christian down on his knees. It was Dean, a member of our own class. A couple of other guys lit candles and placed them in a half circle behind him.

Physically Dean was completely average; intellectually he was right off the scale. The results of an IQ test he had taken the year before were so impressive that colleges and universities were already calling the monks from as far away as England. The actual score was a tightly held secret.

Dean was one of those guys who could be cool one minute, moody and withdrawn the next. We tried letting him hang out with us for a while the previous year, but he didn’t have much to say. He was too wrapped up in his own thing, so we let him slip back into obscurity. Now, in the flashlight beam, Dean folded his arms and rolled his eyes.

Connor Atkins was also intelligent, but he shone as the natural athlete of our class. He filled out faster and better than the rest of us. There was an eternal energy about Connor—the way he moved in bold, fluid gestures. He seemed anxious at rest, fully realized in motion. Because of his stutter, he felt more articulate using the language of his body.

Rolling up the sleeve of his T-shirt, Connor made an impressive muscle. Even in the candlelight we could see the glint in his blue eyes and the green vein on his hard right biceps.

“I’m shaking,” Dean said, putting his hands on his hips.

“Say ‘Hail Caesar’ or j-j-join the s-saints,” Connor ordered.

“Hmm. How ‘bout ‘Fuck you’ instead?”

Everyone gasped. Connor smiled, turned as if he was going to let it go, then pushed Dean onto his ass and into the candles. The Romans went wild.

“G-g-get in 1-line,” Connor commanded.

Dean got in line with the four other Christians, then I pushed mine down on the shoulder until he was kneeling in the candles. Standing in front of him, I cracked my knuckles and said, “I don’t want this to get ugly.”

The kid instantly burst into tears. He sat in the dirt and covered his face as Eric arrived on the scene. “Bill! What did you do to him?” Eric pushed people aside to get at me. “You’re not supposed to hurt anybody.”

Eric Dumont had an overly developed sense of right and wrong. He was the most religious kid I had ever met—forever trying to recruit people into the Knights of Mary or some other holy society. He wasn’t really effeminate, but he had the long, slender hands of a woman and was always meticulously groomed. Eric’s hair was his favourite feature. It never yielded to gravity or wind. Dishwater-brown, it was always parted in the middle and flipped back over his ears, Bee Gees-style, and lacquered in place with mousse and hair spray which, along with all hair products, were illegal at Saint John the Divine. He forgave himself this transgression. Sometimes to mask an acne rash growing in that slick, shiny area of his forehead, he’d comb half his bangs down and zap them in place with an extra dose of hair spray that made him look even more ridiculous. We had always been friends, Eric and I, but sometimes I wondered how it all had happened in the first place.

“I didn’t do anything!” I said. “I didn’t even lay a finger on him.”

Eric was right. The first day of class and I had humiliated this kid in front of half the school. The other half would know before their heads hit their pillows. I apologized, then reached out my hand. He took it. I pulled him up and tried to force a smile, but it was much too late.

“It’s just a game,” I said. “I didn’t—”

“Line ‘em up.” Connor took control, and Michael Ashbury fell in with the other Christians. One of the Romans looked at his watch and announced it was ten minutes to rosary. We formed the gauntlet.

Each Christian was given the final chance to say “Hail Caesar.” One of the freshmen caved in and was set free to live in shame. The others were then pushed one by one between two rows of Romans who slapped and shoved, cursed and cuffed the Christians as they passed through. Most put their heads down and ran, receiving little real damage. Eric walked in a slow, dramatic procession, head held high, letting each of us get two or three shots in before he reached the end.

When it came to my Christian, I looked away. I wanted him to have a chance to say his “Hail Caesar” without making it worse than I already had. But Michael Ashbury took a deep breath, let out a weird little laugh, and charged through the Romans. I gave him a cuff on the back of the head, but not too hard. Just enough to let him know I wasn’t babying him.

An almost life-size crucifix loomed over the altar in the student chapel. It was abstract, in the style of the 1960s. Carved from white marble, it looked as much like a mummy or a cocoon as a replica of our Lord in agony. In the back corner of the chapel a more normal statue of the Blessed Virgin stepping on a serpent kept watch over us from behind. A solitary kneeler was parked directly in front of Our Lady’s feet. Eric often said his rosary there. On three of the four walls were the Stations of the Cross below a row of small square windows. The windows were up high and made of coloured, textured glass like the kind found in washrooms and other places where people shouldn’t look in.

There, on its knees under the fluorescent lights, the student body mumbled through never-ending prayers. Each one served to remind me I was straying farther from a state of grace. The Finger of God, it seemed, was pointed directly at me, and I cursed all parents who had christened their daughters Mary.

“Hail, Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou among women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus... “

Mary O’Brien was a local girl whose family came to Mass every Sunday morning. She had spent her entire life below the cliff in Ennis, the bell tower and Mount Saint John her inescapable points of reference. Toward the end of the previous year we started going on walks together. I made her laugh; she gave me impure thoughts. This sort of “fraternization” had to be kept away from school grounds. The monks couldn’t have us “strolling up and down the drive with every girl in town.” I guess they had more faith in our ability to be desired by local representatives of the opposite sex than we did.

The Sunday before the end of the spring term Mary and I had stolen away to the path behind the Bog. We ended up on the bench in front of the secluded statue of Our Lady of the Lake, a place created for quiet, holy meditation. She sat smiling on the bench in the dappled maple light. My hand wasn’t exactly up her blouse, but I could see how it might have looked that way from a distance. We were making out, I admit, but Brother Thomas wasn’t interested in hearing my defence.

“Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death. Amen.”

The rosary was made up of three groups of five Mysteries each. The second group, the Sorrowful Mysteries, included events in the Lord’s journey through the streets of Jerusalem on His way to crucifixion. We took turns reading the brief descriptions out of the prayer book about how Saint Veronica wiped the face of Jesus or how Simon of Cyrene shouldered the cross for a few steps. You were supposed to dedicate each Mystery to some pressing international concern: the conversion of the Soviet Union, the relief of the famine in Ethiopia, or world peace were all acceptable selections. Then it was Michael Ashbury’s turn to take the lead. We juniors were kneeling five pews back, so all I could see was his skinny little neck.

“I wish to dedicate the next Mystery to the upperclassmen at Saint John’s,” he said. “For more maturity in certain juniors and seniors so they won’t pick on kids smaller than them this year. Hail, Mary, full of grace...”

At the end of rosary Jon nudged my shoulder and gestured to the stairwell where Father Gregory was beckoning me. I squeezed out of the pew and genuflected toward the Blessed Sacrament. Then Father Gregory led me down the empty hallway past the open classrooms, the hem of his habit fluttering nervously behind him.

Father Gregory was the rector or headmaster of the seminary. That meant our day-to-day welfare was in his hands. He was our surrogate parent/prison guard. He was also a serious man who had about twelve doctorates and who read the Latin version of the Bible—with the Greek and Hebrew cross references in the margins—just for fun.

He had bad dandruff, and it collected on the inside of his glasses in a filthy haze. Trying to establish eye contact with him was frustrating. I wanted to take his glasses off, wipe them on his habit, then put them back on his face so I could see him better. Let’s just say he wasn’t one of those monks you could imagine boozing it up with Robin Hood and the Merry Men after hijacking the king’s coach. Besides, he was too old—at least 108, it seemed. He often mentioned living through eight popes in much the same way other old people talked about having survived both world wars. But despite his age he was strong and imposing. He was still over six feet tall.

Father Gregory’s office was known as the Cave. Although it was right off the foyer in the heart of the seminary, we rarely had cause to enter. It was both intimidating and exotic. This was the place your dad came on Parents’ Day and sat with you across the desk from Father Gregory. It was here that you suddenly realized your old man was almost as afraid as you were.

The door to the Cave opened on a long, narrow hallway that led to a dimly lit office with about two thousand books covering grey stone walls. Only half of the titles were in English. Everything was neat, dusted, and in its place. The only thing betraying human habitation was a newspaper tossed a little haphazardly onto the Naugahyde couch. Presiding sorrowfully over everything was a big Russian icon of the Madonna and Child.

Behind Father Gregory’s teak desk was a large window that looked out onto the middle of a colossal rhododendron that had grown into a small forest. The Cave was on the main floor of the seminary, and the dormitory wing above—particularly the window over the sinks in the washroom—could be clearly seen from my seat. I knew Jon, Connor, and Eric were probably up there with the lights turned out, watching us and making up dialogue as they saw my lips move. I tried to keep from looking.

“How are you settling in this year?” Father Gregory had my file out. It, and an antique fountain pen, were the only things on the desk. Every seminarian had one of these neat dossiers with lists and dates and records of everything you’d ever done or were likely to do. He hovered over a page, scratched something in there with his old pen, then finally looked up, waiting for my answer.

“Uh, fine. I guess.”

“Doesn’t sound very definitive to me.”

“Great. Everything’s great.”

“Have you had time to put any more thought toward your vocation?”

At the end of the previous year I was invited not to return to Saint John the Divine. The inventory of reasons included attitudinal problems, a questionable dedication toward a religious vocation, a general lack of respect, a tendency to incite rebellion, and the “liaison” with Mary. I was given the summer to pray, think things through, search my heart, and try to come to some conclusion about whether I should return for my third year a “new man” or stay at home and make the best of public school.

“I’m back, aren’t I? I want to be back.”

Father Gregory scribbled something else. “Where do you see yourself in ten years?” It was the priesthood question in another guise.

“Well, maybe teaching religion someplace like Rwanda. Maybe I’ll become a Jesuit.” The monks hated the Jesuits, only they couldn’t admit it. We said things like this just to make them mad. “But I’m not even a senior yet. Who knows what they’re going to be when they’re sixteen?”

He squinted a little, then leaned back in his cushy chair. Shadows moved in the washroom window above his head. “Don’t you miss your family and friends back in Calgary?”

Well, actually, my only friends were interred here on Saint John’s thousand acres. Father Gregory knew that. The group I had grown up with back home had gone off in such entirely different directions that I hardly had anything to say to them. My brother and sisters were all off in their own lives, busy putting our family behind them. For some reason much was expected from parents who’d done almost nothing themselves. My mother worked at the Calgary “International” School of Beauty. My father, a postal worker and regional union representative, believed in progress and often said he’d be damned if he was going to let his kids grow up to sort mail or tint hair.

“No one expects you to take vows yet,” Father Gregory said.

“We’re already living a life of poverty, chastity, and obedience, aren’t we?”

He smiled, took a deep breath, and carefully placed the pen on the file. Locking his gaze between my eyes, he dared me to look away. “Let’s be specific. Do you see yourself as a brother or a priest?”

I hesitated only for a moment. I felt I could trust him. “I don’t know, Father. Were you absolutely sure when you were my age?”

“Fifty-two years ago—1930—I was your age. I was living at St. Cuthbert’s Abbey in New Brunswick, and there was nothing I wanted more in the world than to become a priest.”

He rested his hands on the desk and looked over my head at the ceiling, thinking back half a century. I glanced above his head and through the darkness, squinting into the third-story washroom window, certain I could see something move. The lights came on and there they were, waving, jumping up and down, making faces. Then the lights went out again.

“My parents were killed in a train wreck when I was eleven,” Father Gregory said without the slightest hint of emotion. “My sister was sent to a convent and I was sent to the abbey. The monks raised me to love God and to listen to Him, to listen for a calling. But from my earliest recollection I knew I’d become a priest. I also wanted to become a professional baseball player, mind you, but I knew that wasn’t in the cards... So, no, I don’t think it’s outside the realm of possibility for a young man your age to have some inkling God may be calling him.”

This was the offer of a fresh start, the hand of friendship extended. It was my chance to suck it up, to submit. But something inside me wouldn’t let it happen.

“Did you ever think, even for a second, that the death of your parents had something to do with your decision to become a monk?” I asked. “You practically grew up in a monastery. I mean, it wasn’t a normal childhood. And maybe if your parents had lived...”

He didn’t say anything, just stared at me. Then he bent over and wrote something in the file, paused again, noted something else, flipped it closed, and pushed it aside.

“I mean, I see your point, with your story and all, but—”

He raised his hand to stop me from making it worse. “This is a pivotal year for you, William. A pivotal semester. We’re here to show young men what a religious life is like, to help them find their vocation. That’s what this place is all about. It’s a seminary, not a cheap boarding school. You have some more thinking and praying to do.” He gestured toward the door. “Join your confreres, but understand, you won’t be indulged any longer. You’re a young man. Being a man means having to make decisions. I’ll pray for you. Please pray for me.”

At 12:07 a.m. the sound of a distant splash made it all the way to the open window of our dorm. I heard it again, then some murmuring. It was coming from the Bog. I slipped out of bed and tiptoed to the window.

To keep the world out and our attention in, the dorm windows started six feet off the floor. I stood on a chair and leaned on the cool tile sill. The butternut tree blocked most of the view, but I could just make them out through the crook of a bare branch. It took my eyes a while to adjust, but when they did I saw five or six silhouettes in the half-moon light. They were too far and too dark to make anything out, but I knew they were freshmen. There was a pause, a small splash, someone speaking, then silence. I had to hold my breath and cup my ears to hear anything. When it happened the third time, I remembered. They were being baptized tonight, and Michael Ashbury would be among them.

Aside from Romans and Christians, which everyone played, new seminarians didn’t undergo systematic hazing at Saint John the Divine. They were baptized instead. I heard another splash and remembered my own Bog baptism two years before. The ritual was always performed by sophomores and had been going on almost as long as the seminary itself. Unlike the current evening and its heat wave, that night was cool and cloudy. I stood in the muck up to my knees in almost total darkness and listened to the words—a not-so-clever send-up of the Apostles’ Creed.

“Do you believe in Saint John’s and the Spirit of the Sem?”

The kid in front of me, the one about to get pushed underwater, said, “I do.”

“Do you believe in loyalty, courage, bravery, and truth?”

He did.

“Do you believe in the sacred brotherhood in which you are about to share?”

That, too.

“Do you believe in seeking, supporting, fomenting, and aiding REDRO at all times and under all circumstances?”

He nodded.

“Then I say, Spirit of the Sem, come down on this man and make him one of us this day and forever more.” Here the initiate’s head was pushed underwater and held there while the sophomore pronounced, “I baptize you in the spirit of REDRO.” He made a counterclockwise circle in the air with his left hand as everyone answered a hushed amen.

REDRO was our call to anarchy, REDRO was the mission to pull at the loose threads wherever they were found, to resist in ways big and small, to undermine the monks’ total control. REDRO was about fighting for everything boys had a right to be. REDRO was ORDER spelled backward.

When it was my turn, I listened to the words refract underwater, the cool blackness enveloping me completely. It seemed to go on forever, and my only tie with the surface was the hand holding my head down firmly. Eventually I panicked and pushed upward, trying to reach the air. But I just sank farther into the mud. The boy at the other end of the hand was now silent, and by the time the amen finally reached my ears, he was already lifting me up by my jersey, pulling me back from the murky water an entirely new man.

“What are you doing, pervert?” Eric demanded, interrupting my recollection. He was standing behind me in his pajamas, arms folded across his chest. Jon stood behind him, rubbing his eyes.

“Baptisms tonight,” I said.

“No, freak. Why are you standing there naked?”

I wasn’t naked—I was wearing underwear—but at Saint John the Divine the absence of pajamas constituted nudity.

“You’ll get in trouble. Again.” Eric hopped onto the chair beside me and looked past the butternut tree, thinking no doubt of his own freshman baptism. Jon waited until I stepped down, then took my place on the chair with Eric to watch the last kid get dunked. But the pair soon shuffled off to bed and the dorm was quiet once again.

I heard the cellophane flap of dragonflies through the open window. It reminded me of when I was a kid chasing fireflies down at my grandfather’s house in Texas. I thought that if I could find one this far north I’d catch it, tie it to a little loop of string, and slip it glowing down Mary’s finger by the moonlit Bog. She was the kind of girl who would appreciate that sort of thing. I kept thinking of Mary, and it became impossible to sleep. To keep my hands from distraction, I clenched them in prayer.

Make me pure, oh, Lord. Make me strong. Don’t give up my seat in heaven.