Читать книгу Prince - Brian Morton - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

In 2004, Prince released an album called Musicology. Like the first two albums, it is neither bad nor great, and for much of its length merely competent. No one expected the forty-six-year-old to make another Sign ‘O’ The Times, or even a Dirty Mind, but after a run of indifferently received albums another disappointment would have rated as a technical knock-out. In the event, it wasn’t so much treated as a win on points as a sign of recovery, the work of a man who’d come back from a very bad place, calm and rebalanced, less paranoid and vituperative. Prince was Prince again, no longer The Artist Currently Known As Wanker, ‘Squiggle’ or ‘SLAVE’. In the first showcases, he spoke warmly in that unexpected baritone about loyalty to the fans who’d stuck with him, and he delivered an album full of gentle seduction (more Marvin Gaye than Rick James), jazzy soul and power pop.

The fans attributed much of its success to a set of words that appeared over several of the tracks. They were a reminder of where Prince had begun in 1978. The major credit line on For You reads ‘Produced, Arranged, Composed and Performed by Prince’. Lest there be any ambiguity, the publisher details run ‘All selections by Ecnirp Music Inc’. In Prince: A Pop Life, Dave Hill quotes the album’s executive producer Tommy Vicari, somewhere between admiration and exasperation, asking Prince ‘Why don’t you press the record and take the picture as well?’ No sooner said than . . . ‘Dust Cover Design by Prince’.

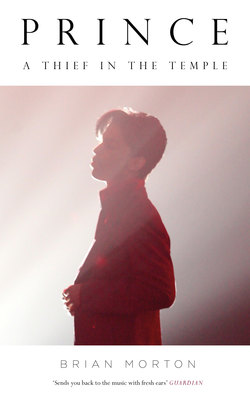

The actual photography on For You is by Joe Giannetti. It catches the producer/arranger/composer/performer/dust-cover designer in blurry soft focus, his towering Afro backlit, the look guarded rather than lustful or defiant. But for a shadow of moustache, it might almost be the young, pre-surgery Michael Jackson. It is a low-key image and it fits the product, because For You is certainly not the epoch sometimes claimed; like its distant successor Musicology, it now seems fussily competent rather than organically brilliant, interesting as a first exposure to Prince’s distinctive coalition of funk, tv jazz and heavy rock, interesting above all for the circumstances in which it was made.

* * *

Central to the Prince mythology is that he was the first black musician to cut free of corporate interference and insist on control of every creative dimension of the music. Even if the latter part is true as read, he certainly wasn’t the first. eBay browsers occasionally turn up albums by the Jimmy Castor Bunch, in fact Jimmy Castor himself, as the silhouette-only images of the other band members might have given away. Jimmy played just about everything you heard. Somewhat up the creative scale was Stevie Wonder, who turned twenty-one in 1971, came of legal age and, benefiting from earlier in-fighting with the label by the self-driven Marvin Gaye, made what was effectively a shotgun contract with Motown which allowed him to write, produce and perform his own work.

By then, though, Stevie Wonder was a veteran, having been spotted by Berry Gordy at the age of ten, and with an enormous amount of second-hand studio knowledge and market awareness. Even so, Wonder’s independence shouldn’t be exaggerated. His greatest albums are the fruit of collaboration, specifically with synthesizer wizards Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff of The Original New Timbral Orchestra, better known to record buyers of a certain age as Tonto’s Expanding Headband. When Stevie split with them later, convinced he’d mastered their skills for himself, his work went into sharp decline. By the same token, Prince’s celebrated independence on For You and after needs to be examined more closely.

The only exception to Prince’s sole credit on For You and the reason there’s a little asterisk beside ‘Composed’ is that the lyrics to the album’s first single ‘Soft and Wet’ are attributed to ‘Prince and C. Moon’. He’s the same C. Moon who’s thanked along with God, Mum and Dad, Bernadette Anderson and a slew of Minneapolis friends and bandmates. He’s also the same Christopher Moon who turned up in the office of the Minneapolis businessman Owen Husney announcing he’d found the next Stevie Wonder.

Both white men – Moon is English by birth and Husney Jewish – play a central part in the Prince story. Husney’s advertising background allowed him to lay siege to the major labels in the most blatant way. His schtick was a good one. Here was a black kid from Minneapolis – virgin territory as far as New York and San Francisco executives were concerned – who played all the instruments and sang all the voices on Moon’s demo tape. If his first reaction was surprise and delight – and Husney was an amateur musician with a bit of band experience – then surely there was someone out there who’d share that response and clinch it with a signature?