Читать книгу Prince - Brian Morton - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

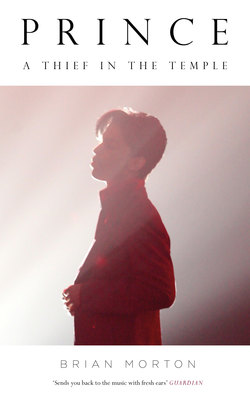

London, 1988, and the auditorium of an old theatre, not quite West End, not yet sleazy. It’s not the obvious setting for a rock concert and unusually the curtains are down. The audience feel uncomfortably like voyeurs. From behind the red plush curtains, a deep carnal throb. Then a dark slit opens up, its edges lit from behind, crimsoned in excitement. Caught in the same rear spotlight, a tiny figure in purple, improbable clash of colours, unmistakably raw symbolism. Not dancing, not running, but sprinting in place; head forward, legs flashing out behind, high-heeled boots like satyr’s hooves pounding the stage; face caught in an expression that could be lust, fear, anger, delight, or all of them. Tantrum child and exhibitionist: Look at me, Dad! . . . Mom!

For a heart-racing minute the beat and the volume increase. And then someone steps out from the shadows and hands him an instrument that seems to sum up every Cultural Studies module on ‘The electric guitar as phallus’, except that this one seems also to represent a question mark, an infinity sign and the astrological symbols for male and female. The curtains swing fully back and the lights plunge and sweep over a stage littered with keyboards, drum risers and propped guitars. There are other musicians on the stage, looking momentarily startled, like tomb-raiders caught in a burst of sunlight.

* * *

Seven years earlier, in the New York Times of December 10, 1981, the critic Robert Palmer had published a story headed ‘Is Prince Leading Music to a True Biracism?’ Questions in NYT headlines are invariably rhetorical. In the article itself, Palmer rather more carefully voiced the growing consensus that a twenty-three-year-old from Minneapolis – not a moving and shaking town in music terms – had overturned a basic industry nostrum about audience colour, and in the process answered the old question about how to take the black and white out of popular music without leaving it grey or beige. In three albums, or rather in the third of his three albums to date, Prince had restarted the faltering progress of black rock.

His own sense of history is impressive, not just because he claims a prominent place in it but also because he displays an eclectic knowledge of what went before. On that night in London, more than half a controversial decade after Palmer’s essay, words like ‘protean’ and ‘mercurial’ seemed insufficient.

* * *

It’s unusual to see closed curtains at a rock concert, but Prince has always occupied the place where music blurs into theatre and theatre blurs into exhibitionism. In that sense, he is the heir of Little Richard, whose piled-up hair, gigolo moustache and falsetto shrieks resurfaced in Prince. Perhaps only Madonna has pushed harder the idea of pop as illicit spectacle.

Indeed, she was to follow him to London on an earlier visit in 1984. He was touring Purple Rain, a quasi-autobiographical album-cum-movie soundtrack that was eventually to shift 13 million copies. The fact that his breakthrough album was tied in to a certain mythology about his upbringing and emergence in Minneapolis was deeply significant. The movie is an adolescent wish-fantasy. What makes it different and clever is the way Prince and director Albert Magnoli manage to weave together themes of display, abandon, secrecy and forbidden longing with cross-threads of responsibility, guilt and self-control. The Kid’s motorcycle is laughably phallic, but doesn’t he ride it with impressive care and road sense? And isn’t there something unexpectedly tender, almost husbandly, about his seductions?

* * *

There was nothing remotely uxorious about his horny, blatant onstage persona, which had moved on from the black panties, boots and bandanna phase, but in 1988 still hadn’t quite yet reached the stage where Prince disported on a heart-shaped bed with one of his dancers. Fans of Prince have a tendency to conflate many concert appearances into one climactic gig. In the same way, Miles Davis’s comeback tours in the 1980s – equally spectacular in the wardrobe department, though inevitably cooler in demeanour – all seem to blend together into one continuous performance.

I have false memories of that first gig, which has become a kind of composite. Clothes, songs and other guitars from earlier and later in Prince’s career seem to be part of it. The curtain wasn’t sensuous velvet, but an ordinary fire-curtain pressed into dramatic service. The supporting personnel shifts, combining the adolescent-male pack behaviour of the early groups with the weird mix of exploitation and feminism of later line-ups; like singer Robert Palmer, Prince was capable of presenting women as cloned sex-objects, but he also operated an impressive gender democracy, giving the likes of Wendy Melvoin and Lisa Coleman a prominent role in the Revolution group and putting his production and songwriting weight behind a whole series of female acts. Again, much like Miles Davis’s last decade, conscious, fact-checked memory will yield one set of impressions (mostly of impressive band members and evolving repertoire) while a more primitive recall narrows the focus to just the leader and what appears to be a single, ongoing, history-of-black-music guitar solo.

* * *

The other word, after ‘protean’ and ‘mercurial’, routinely applied to Prince is ‘seminal’. Ever a man to push his metaphors with excessive literalism, Prince used to feign ejaculation over the first few rows, jerking a milky liquid from the neck of his guitar. (I have no false memory of being so showered, and would seek immediate counselling if I had.) What does come back is how aggressively Prince had plundered the tombs and temples of American music, and how adroitly he personalised the masks and trappings. And how comically: if subsequent chapters fail to deliver a convincing account of the humour in Prince’s art, that’s because it is so wryly and ironically embedded in otherwise serious things.

He’d been widely touted as the reincarnation of Jimi Hendrix. In reality, Prince’s guitar style has little to do with the blues and owes far more to the sustained, almost mystical tonality of Carlos Santana. He was eager to oblige, though, playing behind his head and picking strings with those strange pointy teeth he prefers to keep hidden during interviews. There were subtler echoes, not least that just about every song turned into a long, loose, electronic jam, but turning his back on the audience for long minutes seemed an echo of Miles Davis’s most ambiguous gesture, which some said was contempt for whitey, others claimed was a sign of his concentration and empathy with the band. In Prince’s case, it may have been no more than a tease, a way of showing off his ass, but he knew where it had come from. Prince deeply admired Miles’s working methods – taping hours of ‘rehearsal’ in a bid to push himself and his fellow musicians beyond comfortably familiar idioms – and often alluded to the trumpeter’s phenomenal workrate as a model for his own hyperactivity. As Prince left the stage, the band played a rocked-up version of the bebop classic ‘Now’s The Time’, by Miles’s one-time employer Charlie Parker, whose shambolic lifestyle masked and eventually foreshortened a brilliantly intuitive talent. Prince reportedly still keeps photographs of both men on his desk at Paisley Park.

That night in 1988 Prince duck-walked like T-Bone Walker and Chuck Berry, wailed righteously like Little Willie John, mugged and flounced like Little Richard. One minute he was stock-still, hypnotised by a version of Stevie Wonder’s lateral jazz-soul; the next he was doing endless splits to a relentless funk groove that even James Brown and the JBs would have felt had been taken too far. He sang an intense gospelly song that inescapably recalled Al Green, who took very literally black soul’s sometimes easy, sometimes contradictory blend of sacred and profane by becoming a church minister (albeit a minister who cheerfully ogles pretty girls during his warm-up addresses). British audiences wouldn’t have been so quick to spot references in the stage act to Rick James’s marriage of soul and live sex show; James, with whom Prince toured in 1979, never really made it this side of the Atlantic. They would, though, have recognised the debt to Sly and the Family Stone, primed by the shared vocals of ‘1999’ (one of his first British hits), by a slew of references in the Purple Rain movie, and by the faux-illiterate spelling of songs. In 1970, Sly had released ‘Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)’ with a Larry Graham bass groove that influenced everyone from Prince to Michael Jackson. Though Prince stopped short of calling his first album 4 U he’d adopted the street shorthand style, which in those days came from graffiti and school slambooks rather than phone-texting. As well as 4/fors and U/yous, his liner notes were littered with eye/I graphics, hearts and squiggles, something he’d done since schooldays. It wasn’t to be very long before he adopted an unpronounceable squiggle as his name.

What complicated Prince’s clever referencing of black music and prompted journalist Robert Palmer’s rhetorical headline was his parallel interest in white rock and white songwriters. There was a working assumption in the industry that black musicians didn’t – or couldn’t – rock, and neither did black audiences; r’n’b, soul, funk, perhaps a leaven of jazz, but a fundamental resistance to the basic backbeat of rock’n’roll. There were other, concurrent efforts to inject some life into what sprouted capital letters as Black Rock (notably Vernon Reid’s Living Color) but it was Prince who smudged the distinction and desegregated pop demographics. Jimi Hendrix had shown the way in some regards (and was Reid’s role model) and, of course, Michael Jackson’s Thriller had attracted huge sales with an audience who didn’t usually buy r’n’b.

Hendrix’s and Jackson’s success were to some degree accidents of musical history. Jimi’s style, stagecraft, and eager recolonisation of white blues rock came to notice first of all in Britain; the Experience trio was two-thirds white and they had a white manager. In a somewhat different way, Thriller filled what seemed like a creative vacuum in pop music, left since Stevie Wonder’s muse deserted him. What made Prince different was that he was also able to write and play convincingly colour-blind music. Long before the well-crafted psychedelia of Raspberry Beret, Prince was in thrall to The Beatles. He could also windmill and crash out power chords like Pete Townshend of The Who, and one of the unexpected influences of his teenage years in Minneapolis had been the ‘bicep rock’ of Grand Funk Railroad, still possibly the noisiest band ever.

Onstage, Prince didn’t have quite the range of vocal styles available to him in the studio, but a clear and steady falsetto was one of them and, though it made reference to the peerless Curtis Mayfield, there was no mistaking in it an unlikely debt to Joni Mitchell, especially the laid-back mystery and buried tension of The Hissing of Summer Lawns. It’s an influence that can still be heard on 1987’s ‘Starfish and Coffee’ from the brilliant Sign ‘O’ The Times album, but it’s pervasive. ‘She taught me about colour’, he said to a reporter, though in this case at least he meant voice and instrumental colour rather than the industry demographics he was in the process of changing. Elsewhere, he credited Joni with shaping his understanding of space and silence. In turn, Mitchell acknowledged the impact she’d had on him: ‘Prince has assimilated some of my harmonies, which because they come out of my guitar tunings, is unusual. A lot of the time my chords depict complex emotions . . .’

* * *

Such eclecticism is not unusual in black music. To some degree, it defines it. So Michael Eric Dyson argues in his book Between God and Gangsta Rap, published in 1996, the year Prince’s grasp on that rich dichotomy seemed to come temporarily unstuck. To what extent Prince’s cherry-picking, not just from within the black tradition but between traditions, was new or merely different in degree is scarcely important. What is beyond doubt is that the music of the 1980s and after would have been radically different without him. His most distinctive albums – Dirty Mind, 1999, Purple Rain, Sign ‘O’ The Times, Emancipation – are all contemporary classics. Between 1978 and 1988, he matured, not just as a songwriter and musician, but also as an engineer and producer, turning the slightly fussy feel of his first two albums, the antithesis of a home-made, punk aesthetic, into product that major labels and studios couldn’t match. At the same time, his vehement reaction to corporate pressure became a model for other musicians stuck with no-win contracts or creatively restricted by the men on the twenty-fifth floor. (He put in a call to George Michael during the British singer’s battles with Sony.) Whether Prince really created a new, ‘biracial’ music or was merely a gifted eclectic, less an innovator than a brilliant assimilator who fashioned his own creative environment by plunder – sometimes rich grave goods, sometimes overlooked shards – remains the question. The background to it, if not quite the answer, lies in Prince’s upbringing in a quiet Midwestern city.