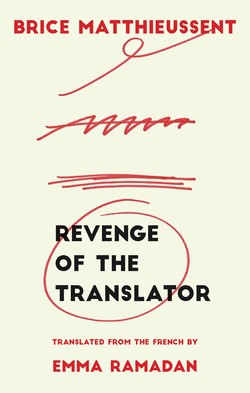

Читать книгу Revenge of the Translator - Brice Matthieussent - Страница 34

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление*

* A recurring nightmare I used to have as a child also feels worthy of being added to my author’s text. In this nightmare, it’s neither day nor night and I’m freefalling through an undefined black space, in the grips of a violent vertigo and a complete loss of any sense of direction, between the walls of what I imagine to be a bottomless pit, a bit like the unlucky hero of “A Descent into the Maelström,” the story by Edgar Allan Poe. Then a fading into darkness, a terrifying blackout. An ellipse, a hole in the narration. Then I climb back up inexplicably, with no tether to any ground or gravity, I am weightless, levitating, or else a shell spurting from a cannon pointed to the sky. Soon I reach the summit of my trajectory, where I am immobilized for a moment in the grips of a retching that leaves me breathless, before starting on another freefall, more and more rapid, more and more panicked. Another fading into black, another loss of consciousness. This entire sequence repeats again and again, with no respite, an inexorable swinging motion. From high to low, then from low to high, given over entirely to this metronomic mechanism, whose purpose I do not know. In a certain way, I suffer like the condemned man of that other story by Edgar Allan Poe, “The Pit and the Pendulum,” but unlike him I have no means to change my destiny or save my life.

For several months of my childhood, I went to sleep every night with the obsessive fear of reliving what I believe today to be the very terror of torture: to know you are given over to an unfamiliar and evil will. But my nocturnal terror was not of a human executioner, merely—which is perhaps worse—of a relentless mechanism, unfamiliar, incomprehensible, absent. An inhuman machinery would launch me toward the black sky, then bring me back down to an unknown depth, again and again.

This repetitive nightmare reminds me of the Goya painting The Straw Manikin. I’ll describe it briefly. Four smiling, certainly cruel young women each hold a corner of a large square blanket over which hovers a puppet in men’s clothing, larger than a child, smaller than a man. Hard to say whether this dislocated mannequin is flying toward the cloudy sky or falling back into the blanket; he seems to float weightlessly, hands and legs sadly turned toward the earth, head curiously tilted toward his shoulder, like a hung man with a broken neck. Beneath his white face made up with blush descends a long black braid curved in the form of a flaccid penis, isolated, backlit, strikingly positioned in front of the most luminous part of the sky. The four young women’s arms are spread wide, as if to welcome the arrival of the stuffed puppet, and they seem delighted with their game, which recommences endlessly. They amuse themselves with the back and forth of the milquetoast who goes up and falls back down at their mercy, obeying the muscles of their arms. In the back and to the left, a massive square tower with a roof of red tiles is hidden in a haze of greenery. This large painting, it seems, is a cartoon tapestry, but it evokes above all a theater stage, and the décor—intangible sun, abundant foliage, half-hidden tower, stormy clouds—resembles a gigantic painted canvas stretched in front of actors, singers, or dancers. (Terrifying Night)