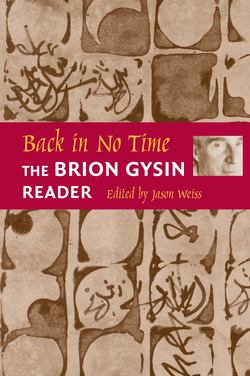

Читать книгу Back in No Time - Brion Gysin - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPotiphar’s Wife

“Potiphar’s Wife” (1950) is one of several stories about life in Morocco that Gysin wrote not long after arriving there. He had been invited to Tangier by Paul Bowles, whom he had known in New York in the 1940s. These pieces were never submitted for publication and only appeared much later in Gysin’s Stories (1984).

The second time he ran away because he had too many elder brothers, Yussef ben Allal El Hamri got a job working with a man who sold pastries from a little cart which rolled through the market of Alcazar Kebir. Yussef had wanted to go to war in the Spanish zone, for he had heard that the Americans were in Morocco, but, as he could never find anyone who could tell him for sure whether they were for or against the Sultan, he allowed himself to be distracted. He had admired the cakes one day when he had not eaten for a long time, and now he was working for Hamid, who made them in his own house.

Hamid payed him four pesetas a day and he rarely went out of the house for fear one of his brothers might see him, take him back home, and beat him. His only trouble was with Hamid’s wife, Zuleika: she hated him. “I’m going to lose this good job; all because of this aunt,” he would say to himself when she complained of anything he did in a loud screaming voice. The trouble had started as soon as Hamid had brought him home on the first night. She had looked at him very closely and said, “You’re not going to have this dirty boy around the house all the time, I hope. Hamid, why do you always want to bring stray dogs home with you?”

“Really,” said Hamid without looking at Yussef, “I hadn’t noticed. Where’s my dinner, Zuleika; what have you made tonight?”

He was a man who shouted at times in order to be sure of his own importance: Zuleika, although she was quite young, knew how to handle him perfectly.

When he was eating she threw a ragged, old grass mat out into the little courtyard of the house where Yussef was sitting patiently waiting.

“You’re too dirty to come in the house,” she said. “You’re too dirty to eat with decent people. Here, take this to sleep on. And here’s your food,” she said, thrusting a plate of scraps at him.

She went on treating him like that, finding fault with everything he did while he was learning and even after he learned to make the cakes as well as Hamid himself. He had learned simply by watching, for Hamid rarely spoke to him either to instruct or to blame him. Zuleika never again spoke to him directly, finding that it humiliated him more to talk about him as if he were a bad dog or a slave in the house.

“I know I’m going to lose this job: I know I am. And all because of you,” Yussef went on thinking to himself all the time.

One day Hamid came back with half the cakes still unsold, saying that he was ill. His wife scoffed at him at first, but it was easy to see that he had a fever for he shook all over. She put him to bed on the floor of the main room and ordered Yussef to take the remainder of the cakes out and sell them. The next day Hamid was much worse and no cakes were made that day. The day after that he looked no better and it began to seem a serious matter, for they lived on a narrow margin like most Moors.

“Give me the money to buy the flour and the sugar and the cinnamon and the raisins and the nuts and the butter and I will go out and buy the things to make the cakes,” said young Yussef breathlessly.

“You?” said Hamid, just managing to raise his head from the pillow.

“You?” echoed his wife. “You?”

Hamid reached under the pillow where he always kept his money and pulled out a bill which he gave to the boy. His wife would have objected, but he closed his eyes and she thought for a minute that he might be going to die.

The cakes were quite as good as usual, and Yussef paid a little boy half a peseta a day to come to the house and get them in order to carry them to a Jewish woman who agreed to sell them for him. That night Hamid called him to his bed to say that he was going to double his wages to eight pesetas. It was easy to see that he was much sicker; perhaps delirious with fever. Yussef went on making the cakes, and Zuleika began to help him when she saw that Hamid was really sick: he was obviously in the hands of Allah, so there was no need to waste her time doing anything for him. Yussef admired her tremendously. She reminded him of the young wife of one of his brothers, who was only a year or so older than he but had bullied him because she was a married woman. He and Zuleika often had their hands in the same big earthen dishes as they were mixing up the things that went into the cakes, and he liked it very much when their hands met. She had to speak to him directly now as they were working together just outside her husband’s room, but she was always curt with him.

All the money of the household was now passing through Yussef’s hands, and Hamid was so ill that he could no longer even keep the accounts. Yussef decided one day how much it was that Hamid owed him, and he kept that money aside to buy new clothes for himself, paying a little at a time and leaving the things in the shops until the time came to get them all out and put them on. He went to the hammam and steamed himself for hours until he felt quite clean and then he put on the new clothes to go to the barber’s where he had his hair well cut and covered with a great deal of brilliantine called “Essence de Violettes,” which smelled very good and very strong.

When he knocked and Zuleika opened the door, she must have thought that it was some stranger for she covered her face and just stood there looking at him for a long time. Then she said, “Ahhh,” letting her breath out. After that she said, “Mmmm,” and it sounded as though a pigeon with its tail out were strutting on the ground between them; her voice came from so far down. That night when she made some broth for Hamid, she came and set the pot of chicken before Yussef who was sitting in the other room and waited until he had put his hands in it before she took any.

Perhaps because the weather had grown colder, she made a bed for him in the other room and laid one of the best rugs on it. He slept there very well, but she lay awake beside Hamid all the night. In the morning she had decided what she must do. When Hamid’s mother and sister came to see him, she began to cry right away, saying he was so very sick that she was afraid he might die at any minute. Her mother-in-law peered into her face, but she looked so haggard from not having slept all night that the old woman decided this outburst must be genuine. Zuleika said that, if Hamid was really going to die, which Allah forbid, she hated the idea of him dying in that house.

“What’s the matter with this house?” snapped the mother-in-law who guessed what was coming although she thought there was quite another reason behind it. “You never complained about it before.”

“But it’s in the Mellah,” wailed Zuleika. “You don’t want him to die in the Mellah!”

“I see,” said the mother-in-law and it was agreed that Hamid should be carried to their house in another quarter of the town.

“I can sleep there with him in your big house,” sobbed Zuleika, “and then I’ll have to come back here every day to see that this horrid boy looks after the pastry business. We don’t want to be entirely a charge on you. That way, there’ll be a little money coming in every day.”

“Hmm, yes,” said the mother-in-law, “That’s quite true.”

“Oh, I know that he will be happier in the house where he was born,” smiled Zuleika through her tears. “I just know he will, although he hardly noticed anything any more. I want to go and get him some water from the holy fountain of Sidi Bou Galem: I know it will do him some good. No, no; I don’t want either one of you to come with me. I’ll take Yussef to carry the water jar. The cakes are made, and that good-for-nothing who has just spent all his money, and the Prophet only knows how much of ours too, on useless new clothes, has nothing to do. Why don’t you just run home and get someone to come and carry Hamid while your mother sits with him a while?”

On the way to the fountain she was very charming to Yussef and told him how awful her family-in-law was and how much she would hate having to live with them. “But I’ll be back every day to look after the house,” she said with a laugh. “In fact, I’ll come twice a day; once in the morning and once at night. Oh, it will be wonderful to get away from them. And for another reason, too. Can you guess what that is?”

“No,” said Yussef dully.

“Silly,” she said.

On the way back from the fountain she pulled him aside on a little side path which led into a field of nothing.

“Why do you want to come this way?” he asked, stumbling after her.

When she turned swiftly to him and cunningly put her two hands on his chest, he said nothing, so she spoke to him; when she asked him again with different words and he said no, she spoke to him sharply. He felt that he could not change his mind which had said no in spite of him; now he could not say yes to her while she was insisting.

She spat at him and said in a low voice trembling with fury, “I’ll kill you, kill you: have him kill you. I’ll tell them you attacked me: here by the saint. D’you hear? They’ll tear you apart … his brothers will kill you. I’ll go now, right now, and tell them. I will; they’ll believe me, they will: you know they will. Kill you, kill you….” She ran after him when he turned up the path.

“You don’t believe me? You’ll see, you’ll see….”

She walked on ahead of him so rapidly that he could barely follow her although she was tripped all the time by her veils. When they got to the house two of Hamid’s brothers were there but she hesitated just at the door, half turned to him with a faltering smile, and Yussef knew that she would say nothing. He had been very afraid for a while, and he knew that he would have a difficult time with a girl like that. They all went out carrying Hamid, and he was left in the house alone for the night.

It was barely light the next morning when she came and Yussef was still asleep; she crawled in beside him without taking her clothes off. When they both got dressed later, she said that she would come back to make his dinner, and she did.

While he was eating she kept urging him to eat more and leaning across the food to stroke his hair. He said that it bothered him. After that, when she first came into the house, she would be almost as she had been before and then she would gradually change, like a cat that seeks to be petted, until she had become quite the contrary.

“Don’t do that,” he said. “Don’t do that all the time. Stop putting your arms around me and wetting my face with your face. I don’t like it when you want to breathe in my mouth. When you feel like that just go and draw two pails of water from the well in the courtyard and put them on to heat.”

Yussef was a very religious boy, and he liked to bathe several times a day on the occasions which the ritual law demands. At first it was like that, and he knew, although he had never had a woman before, that he was a man; acting like a man. He felt that he was more of a man than Hamid, who let her do what she wanted. Before the month was over he no longer felt so safe or so sure. Often, when she came in the morning, he was up already; drawing the water. After that it was always he who drew the two pails of water and then they both went into the room: he went and drew water twice a day, at least.

She was staying longer and longer in the house each day, saying that she really could not stay any longer with Hamid’s family; they were impossible. Her mother and sister began to come and visit her nearly every day. They had not come before because Hamid had said that he did not want to see them in the house all the time because they were on bad terms with his family ever since the wedding dispute. They sat and talked and, when they stayed for meals, having brought a little something with them, Yussef sat down and ate it first as the man of the house should. Because he was so young, one could not treat him as though he were really the man of the house, so it turned into a family meal as though he were still a little boy and they all enjoyed themselves.