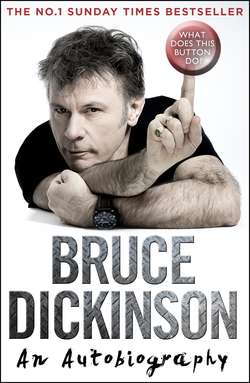

Читать книгу What Does This Button Do?: The No.1 Sunday Times Bestselling Autobiography - Bruce Dickinson, Bruce Dickinson - Страница 16

Going to the Dogs

ОглавлениеIf my account sounds strangely devoid of much in the way of historical studies, that’s because as I progressed to my second year, I wasn’t even turning up to most lectures. Very occasionally, I would drink two or three pints at lunchtime and wend my way into my medieval history tutorial. My tutor was a very nice old lady, and I think she might actually have experienced most of The Cambridge Medieval History she so adored. I can’t remember anything about Charlemagne or Frederick II, but I do remember that the sunshine was very bright and interfered with my daydreams as it streamed through the hazy window that framed her silhouette.

I was now the full-on entertainment officer. I had an office, went to committee meetings and I had a budget. Most crucially, I had a telephone with an outside line and a hotline to every agent in town. Suddenly I had a freshers’ week to organise: booking bands, discos and all that good stuff.

I think I ended up with Fairport Convention as the main event, and the whole week was extremely profitable. I made about 20 per cent on top of my expenditure. I was hauled before the committee and told I was a ‘disgrace’.

‘This is just exploitation of the student body,’ I was informed.

‘So you want me to lose money as a general moral principle?’ I enquired.

After the inquisition, I gave the problem some thought. I had never seen Ian Gillan – one of my vocal heroes – so I phoned up his agent and booked him. Money no object, I said. In return, I suggested, might there be a few pub gigs he could point in my general direction? Speed was fun but constrained. To borrow a song title from my future, I had a ‘Burning Ambition’.

The telephone, of course, gave me the ability to respond to adverts in Melody Maker. One in particular seemed promising: ‘Vocalist required to complete recording project.’ I phoned up. Just one problem: ‘Do you have a tape?’ Of course I didn’t. The guy I spoke to was a recording engineer and also the bass player. It was free studio time, and I had never been in a studio in my life. The influences, though, sounded like a shoo-in for me: Purple, Sabbath and, delightfully, Arthur Brown. He, Ian Gillan and Ronnie James Dio are probably the three singers you could refer to and say, ‘Aha! I see where Dickinson nicked that from.’

I should recount my history with Arthur Brown, one of England’s wackiest performance artists, and one of rock music’s most insanely talented voices. The first time I saw him was at Oundle when I was 16. Kingdom Come was the band, and the album was called Journey. The concert was, for me, a mind-blowing shamanic ritual. I have never tried acid or mushrooms or any hallucinogen, but with Arthur that night I didn’t need to. Deep, deep analogue-synth sine waves scooped your eyeballs up and planted them in stereo where your ears should be. The single screen of blobs and lights and stars compressed time to a singularity.

Then Arthur hit the stage dressed in face paint and a gigantic headdress, standing like an Aztec king before a gigantic tripod, and raised his hands in sacrifice and intoned, in a dark, extended baritone, a command to strip the rust from your soul: ‘Alpha waves compute before eternity began …’

Who cares if it sounds like hippy bollocks? I can tell you I thought I had seen a glimpse of God that night.

In 1976 Arthur had a band with no drummer. On top of that tripod was not an altar, but a Bentley Rhythm Ace drum machine. Arthur wasn’t sacrificing or blessing us; he was fiddling with the analogue tape loops of each individual drum, all of which ran at different speeds, and he was probably cursing frequently in frustration. No one but a madman would even have attempted it. There was a lead guitarist and a bass player, and two keyboard players, with every kind of analogue synth going, VCS3, Theremin and Mellotron.

Somewhere in the midst of this falling-into-a-musical-black-hole experience, two fellows came on stage dressed as brains to be beaten with a stick, and men danced around dressed as traffic lights. Inspired and deliciously potty.

‘Fire’ is the best known track of Arthur’s, and this alone is enough to secure him a place in rock’s pantheon, but all of his albums with Kingdom Come and as the Crazy World of Arthur Brown are worth exploring. Pete Townshend was the associate producer of The Crazy World of Arthur Brown – the whole idea of the Who’s Tommy came from it – and it’s a concept album, one of the first, about a man’s descent into hell. When he opens that door, well, you guessed it: ‘I am the god of hell fire, and I bring you, fire …’

There was a black voice trapped in Arthur’s body, because he could strip the paint off walls when he sang blues standards like ‘I Put a Spell on You’. That night I saw him, Arthur planted the seed for what I describe as ‘theatre of the mind’, with music the proscenium arch and your brain as the stage.

Anyway, back to my immediate problem – I didn’t have a demo tape. I would have to improvise. In my second year in London I had moved my lodgings away from South Woodford – a bland, characterless university halls-of-residence tower block that overlooked the motorway – to somewhere slightly more challenging, but so much more interesting.

The Isle of Dogs is the U-shaped bend in the Thames that features prominently in the credits of EastEnders. In the late seventies it was a desolate, windy and decaying place. Tower blocks sat alongside thirties council flats and houses, all built for the thousands of workers who once populated the London docks. In Tudor times it was a marsh and a refuge for criminals on the run from nearby jails. Because of the tidal flow a wall was built, which gradually formed the shape we all know and love. Water-operated mills were built on the wall, hence the Millwall, which ran down the west side of the Isle. Before basins were scooped out of the mud to form the docks, Henry VIII released wild dogs onto the marshes. He was fed up of spending money on chasing criminals, so he made sure the dogs were fed up in a rather more unpleasant sense.

Tate & Lyle still has a sugar refinery there, and tucked away, on Tiller Road, was the ground-floor flat that was my new abode and the location of my first demo recording. I had a flatmate, but I didn’t see much of him, as he would disappear into his lair and only emerge at odd hours of the night. He had long hair, an Afghan coat, goatee beard and John Lennon glasses, and he giggled a lot to himself for no reason I could fathom.

There was an upright piano left stranded in one bedroom. Clearly not the object to sling in the back of the car when your days at university are over, it had a mostly operating keyboard but sounded like a load of dinner gongs being hammered with tortured dissonance. I had a cassette recorder, and only one cassette. On one side was a series of awful easy listening, and on the other I had recorded some Monty Python. Cassette fiends will recall the curious rituals involved in taping over pre-recorded commercial cassettes. I got busy with a piece of Sellotape and then fiddled with the innards of the recorder, and eventually had my cassette poised and paused, standing atop the piano.

I didn’t bother playing the piano, because I couldn’t. I stepped well away from the tiny built-in condenser microphone and just yelled a lot, wailing through scales and letting off a nasal shriek with a couple of different vibratos as it faded away.

I put it in the post, to the PO box listed in the advert. With it was a note in red biro: ‘Here is the demo. If it’s rubbish there is some Python on the other side for a laugh.’

With that, I resumed normal operations. Go to college. Open the post. Avoid going to lectures. Sort out a rehearsal. Daydream a lot. Drink three pints at lunchtime. Go to tutorial. Remember nothing. Make some phone calls to agents. Wait an hour for the 277 bus. Eat something. See the girlfriend. Pub. Bed.

‘There is a message for you,’ I was told a couple of days later, when I showed up to the entertainments office. ‘This guy phoned back about a tape or something.’

I grabbed the message: ‘Call Phil on this number …’

I dialled ‘this number’, and a friendly, enthusiastic Brummie voice answered: ‘Yeah, I really liked the tape. You were doing some mad melody ideas. A bit like Arthur Brown.’

It was 3 p.m. By 6.30 I had found my way to the studio. It was homemade in a garage. Lined with egg boxes and foam it was Abbey Road as far as I was concerned. For a small pro-am studio it was quite well equipped. It had a small drum kit in situ, and lots of cables, pedals and stands to weave past on the way to the vocal booth. I had no idea about recording. I understood what a tape recorder did, and I understood a bit of what a mixer did (mix, right?), but of multitrack recording, I had no clue.

The idea of headphones was totally new; a monitor mix was an undiscovered country.

Phil played me the backing track. The guitar was pretty cool as well, I thought: a little bit Peter Green, early Fleetwood Mac, ‘The Green Manalishi’ feel. The song was called ‘Dracula’, and it had some corny Carry On/‘Fangs for the Memories’-style lyrics, but played absolutely deadpan serious. Try ‘My only sense of humour is in a jugular vein’ and ‘Your neck is on the menu tonight’ as a taster and you get the idea. I started to sing, having learnt the song in the control room. Phil leaned forward and pushed the talkback button: ‘Erm … how long have you got?’

‘All night if you want,’ I replied.

I could see him leaning back to dial a phone number.

Phil played bass and had called his big brother, Doug, who played drums. Together, we all listened back at four in the morning. I had never double-tracked, or harmonised with myself, but I did that night: three-part ascending choir vocals, big doubled choral pieces. If only the owner of the three-bedroomed semi whose garage it was knew what he started that night.

‘We’d better start the band, then, I suppose,’ said Doug.

I was most impressed by the fact that they had a battered blue transit van. It performed parcel deliveries by day, and at night it would turn into the most exotic four-wheeled magic carpet, transporting our merry souls to la-la land until dawn, when we all went back to the pumpkin patch with the rest of humanity. But before we could sprinkle fairy dust into that petrol tank, we had to find a guitarist.

So an ad was put in Melody Maker: ‘Guitarist wanted for pro recording band. Good prospects.’

My God, I came over all a twitter. Pinch yourself, Dickinson, here comes the Big Time.