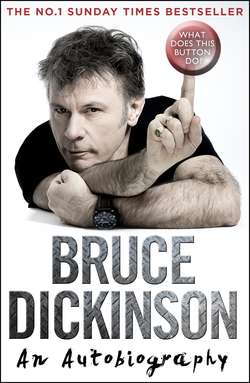

Читать книгу What Does This Button Do?: The No.1 Sunday Times Bestselling Autobiography - Bruce Dickinson, Bruce Dickinson - Страница 8

Born in ’58

ОглавлениеThe events that aggregate to form a personality interact in odd and unpredictable ways. I was an only child, brought up as far as five by my grandparents. It takes a while to figure out the dynamic forces in families, and it took me a long while for the penny to drop. My upbringing, I realised, was a mixture of guilt, unrequited love and jealousy, but all overlaid with an overwhelming sense of duty, of obligation to do the very best. I now realise that there wasn’t a great deal of affection going on, but there was a reasonable attention to detail. I could have done a lot worse given the circumstances.

My real mother was a young mum married in the nick of time to a slightly older soldier. His name was Bruce. My maternal grandfather had been assigned to watch over their courting activities, but he was neither mentally nor morally judgemental enough to be up to the task. I suspect his sympathies secretly lay with the young lovers. Not so my grandmother, whose only child was being stolen by a ruffian, not even a northerner, but an interloper from the flat lands and seagull-spattered desolation of the Norfolk coast. East England: the fens, marshes and bogs – a world that has for centuries been the home of the non-conforming, the anarchist, the sturdy beggar and of hard-won existence clawed from the reclaimed land.

My mother was petite, worked in a shoe shop and had won a scholarship to the Royal Ballet School, but her mother had forbidden her to go to London. Denied the chance to live her dream, she took the next dream that came along, and with that came me. I would stare at a picture of her, on pointe, probably aged about 14. It seemed impossible that this was my mother, a pixie-like starlet full of naïve joy. The picture on the mantelpiece represented all that could have been. Now, the dancing had gone out of her, and now it was all about duty – and the odd gin and tonic.

My parents were so young that it is impossible for me to say what I would have done had the roles been reversed. Life was about education and getting ahead, beyond working class, but working multiple jobs. The only sin was not trying hard.

My father was very serious about most things, and he tried very hard. One of a family of six, he was the offspring of a farm girl sold into service aged 12 and a raffish local builder and motorcycle-riding captain of the football team in Great Yarmouth. The great love of my father’s life was machinery and the world of mechanisms, timing, design and draughtsmanship. He loved cars, and loved to drive, although the laws relating to speed he deemed inapplicable to himself, along with seatbelts and driving drunk. After losing his driving licence, he volunteered for the army. Volunteers got paid better than conscripted men and the army didn’t seem picky about who drove their jeeps.

Driving licence (military) instantly restored, his engineering talents and tidy hand led to a job drawing up the plans for the end of the world. Around a table in Düsseldorf he would carefully draw the circles of megadeaths expected in the anticipated Cold War apocalypse. The rest of his time was spent drinking whisky to drown the boredom and the hopelessness of it all, one imagines. While still enlisted, this beefy Norfolk swimming champion – butterfly, no less – swept my waif-like ballerina mum off her feet.

As the unwanted offspring of the man who stole her only daughter, I represented the spawn of Satan for my grandmother Lily, but for my grandfather Austin I was the closest he would ever have to a son of his own. For the first five years of my life, they were de facto in loco parentis. As early childhood goes, it was pretty decent. There were long walks in the woods, rabbit holes, haunting flatland winter sunsets and sparkling frost, shimmering under purple skies.

My real parents had been travelling and working in a succession of nightclubs with their performing-dog act – as in poodles, hoops and leotards. Go figure.

The number 52 on the house at Manton Crescent was painted white. It was a standard, brick-built, semi-detached council house. Manton Colliery was a deep coal mine, and it was where my grandfather worked.

My grandfather had been a miner since the age of 13. Too small to be legal, he cunningly and barefacedly lied about his age and his height, which, like mine, was not very much. To get round the regulation that said you were tall enough to go ‘down the pit if your lantern did not trail on the ground by its lanyard while suspended from the belt’ he simply put a couple of knots in it. He came close to going to war, but got as far as the garden gate. He was in the Territorial Army, a part-time volunteer, but as coal mining was a reserved occupation he didn’t have to fight.

So he stood in his uniform, ready, as his platoon marched off to fight in France. It was one of these Back to the Future moments, when opening that garden gate and going to war along with his mates would have prevented a lot of things happening, including me. My grandmother stood defiant, hands on hips in the front doorway. ‘If you bloody go I won’t be here when you get back,’ she said. He stayed. Most of his regiment never came back.

With a miner for a grandfather, we got the council home and free coal delivered, and the art of making the coal fire that heated the house has turned me into a lifelong pyromaniac. We did not possess a telephone, a refrigerator, central heating, a car or an inside toilet. We borrowed other people’s fridges and had a small larder, dank and cold, which I avoided like the plague. Cooking was two electric hobs and a coal-fired oven, although electricity was seen as a luxury to be avoided at all costs. We had a vacuum cleaner and my favourite device, a mangle – two rollers that squeezed the water from washed clothing. A giant handle turned the machine over as sheets, shirts and trousers flopped out into a bucket after being squeezed through its rollers.

There was a plastic portable bath for me, as my grandfather would arrive home clean from the pit washrooms. On occasions he would come back from the pub, stinking of beer and onions, and crawl into bed next to me, snoring loudly. In the light from the moon through the wafer-thin curtains, I could see the blue scars that adorned his back: souvenirs of a life underground.

We had a shed in which bits of wood would be hammered and banged, to what end I have no idea, but for me it was a place to hide. It became a spaceship or a castle or a submarine. Two old railway sleepers in our small yard served as a sailing boat, and I fished repeatedly from the side catching sharks that lived in the crevices of the concrete. There was an allotment and some short-lived chrysanthemums that went up in smoke one bonfire night after a rocket went astray.

We had no pets, save a goldfish called Peter who lived for a suspiciously long time.

But one thing we did have was … a television. The presence of this television refocused the whole of my early existence. Through the lens of the TV screen – seven or eight inches across, black and white and grainy – came the wide world. Valve-driven, it took minutes to warm up, and there was a long, slow dying of the light to a singularity when it was switched off, which became a watchable event in its own right. We hosted visitors who came to look at it, caress it and not even watch it – it had such mystique. On the front were occult buttons and dials that turned like great combination locks to select the only two channels available.

The outside world, that is to say anywhere outside Worksop, was accessed primarily by gossip – or the Daily Mirror. The newspaper was always used to make the fire and I usually saw the news two days late, shortly before it was consigned to the inferno. When Yuri Gagarin became the first man to go into space I remember staring at the picture and thinking, How can we burn that? I folded it up and kept it.

If gossip or old newspaper wouldn’t do, the world outside might require a phone call. The big red phone box served as a cough, cold, flu, bubonic plague, ‘you name it you’ll catch it’ distribution centre for the neighbourhood. There was always a queue at peak hours, and a hellish combination of buttons to press and rotary dials in order to make a call, with large buckets of change required for long conversations.

It was like a very inconvenient version of Twitter, with words rationed by money and the vengeful stares of the other 20 people waiting in line to inhale the smoke-and-spit-infused mouthpiece and press the hair-oiled and sweat-coated Bakelite earpiece to the side of their head.

There were certain codes of conduct and regimes to obey in Worksop, although etiquette around the streets was very relaxed. There was little crime and virtually no traffic. Both my grandparents walked everywhere, or caught the bus. Walking five or ten miles each way across fields to go to work was just something they were brought up to do, and so I did it too.

The whole neighbourhood was in a permanent state of shift work. Upstairs curtains closed in daytime meant ‘Tiptoe past – coal miner asleep’. Front room curtains closed: ‘Hurry past – dead person laid out for inspection’. This ghoulish practice was quite popular, if my grandmother was to be believed. I would sit in our front room – permanently freezing, deathly quiet, bedecked with horse brasses and candlesticks that constantly required polishing – and imagine where the body might lie.

During the evening the atmosphere changed, and home turned into a living Gary Larson cartoon. Folding wooden chairs turned the place into a pop-up hair salon, with blue as the only colour and beehive the only game in town. Women with vast knees and polythene bags over their heads sat slowly evaporating under heat lamps as my grandmother roasted, curled and produced that awful smell of dank hair and industrial shampoo.

My escape committee was my uncle John. He forms quite an important part of what button to push next.

First of all, he wasn’t my uncle. He was my godfather – my grandfather’s best mate – and he was in the Royal Air Force and had fought in the war. As a bright working-class boy he was hoovered up by an expanding RAF, which required a whole host of technological skills that were in short supply, as one of Trenchard’s apprentices. An electrical engineer during the Siege of Malta, Flight Sergeant John Booker survived some of the most nail-biting bombardments of the war on an island Hitler was determined to crush at all costs.

I have his medals and a copy of his service Bible, annotated accordingly with verses to give support at a time when things must have been unimaginably grim. And there are pictures, one with him in full flying gear, about to stow away on a night-flying operation, which, as ground crew, was utterly unnecessary – done just for the hell of it.

While I sat on his knee he regaled me with aircraft stories and I touched his silvered Spitfire apprentice model, and a brass four-engined Liberator, with plexiglass propeller disc melted from a downed Spitfire and a green felt pad under its wooden plinth, the material cut from a shattered snooker table in a bombed-out Maltese club. He spoke of airships, of the history of engineering in Britain, of jet engines, Vulcan bombers, naval battles and test pilots. Inspired, I would sit for hours making model aircraft like many a boy of my generation, fiddling with transfers – later upgraded to decals, which sounded so much cleverer. It was a miracle any of my plastic pilots ever survived combat at all, given the fact that their entire bodies were encased in glue and their canopies covered in opaque fingerprints. The model shop in Worksop where I built my plastic air force was, amazingly, still there the last time I looked, on the occasion of my grandmother’s funeral.

Because Uncle John was a technical sort of chap, he had a self-built pond the size of the Möhne Dam, full of red goldfish and cunningly protected by chicken wire, and he drove a rather splendid Ford Consul, which was immaculate, of course. It was this car that transported me to my first airshow in the early sixties, when health and safety was for chickens and the term ‘noise abatement’ had not even entered the vocabulary.

Earthquaking jets like the Vulcan would shatter roofs performing vertical rolls with their giant delta wings while the English Electric Lightning, basically a supersonic firework with a man perched astride it, would streak past inverted, with the tail nearly scoring the runway. Powerful stuff.

Uncle John introduced me to the world of machinery and mechanisms, but I was equally as drawn to the steam trains that still plied their trade through Worksop station. The footbridge and the station today are virtually unchanged to those of my childhood. I swear that the same timbers I stood on as a boy still exist. The smoke, steam and ash clouds which enveloped me mingled with the tarry breath of bitumen to sting my nostrils. I walked to and from the station recently. I thought it was a bloody long way, but as a child it felt like nothing. The smell still lingers.

In short order, I would have settled for steam-train driver, then maybe fighter pilot … and if I got bored with that, astronaut was always a possibility, at least in my dreams. Nothing in childhood is ever wasted.

Somewhere, the fun has to stop, and so I went to school. Manton Primary was the local school for coalminers’ kids. Before it was closed, it achieved a level of notoriety with Daily Mail readers as the school where five-year-olds beat up the teachers. Well, I don’t recollect beating up any teachers, but I was given the gift of wings and also boxing lessons, after a fracas over who should play the role of Angel in the nativity play. I was lusting after those wings but instead got a good kicking in the melee that continued outside the school gates. The outcome was far from satisfactory. When I returned from school, dishevelled and clothes ripped, my grandfather sat me down and opened my hands, which were soft and pudgy. His hands were rough, like sandpaper, with bits of calloused skin stuck like coconut flakes to the deep lines that opened up as he spread his palms in front of me. I remember the glint in his eye.

‘Now, make a fist, lad,’ he said.

So I did.

‘Not like that – you’ll break your thumb. Like this.’

So he showed me.

‘Like this?’ I said.

‘Aye. Now hit my hand.’

Not exactly The Karate Kid – no standing on one leg on the end of a boat, no ‘wax on, wax off’ Hollywood moment. But after a week or so he took me to one side, and very gently, but with a steely determination in his voice, said, ‘Now go and find the lad that did it. And sort him out.’

So I did.

I think it was about 20 minutes before I was dragged away by the teacher and frogmarched home with a very firm grip. My boxing lessons had been rather too effective, and my judgement, at the age of four or five, rather less than discerning.

The ratatat-tat of the letterbox elicited an impassive grandfather: slippers, white singlet and baggy trousers. I don’t remember what the teacher said. All I remember was what my grandfather said: ‘I’ll take care of it.’

And with that, I was released.

What I got was not a beating, or a telling-off, but quiet disapproval and a lecture on the morality of fisticuffs and the rules of the game, which were basically don’t bully people, stick up for yourself and never strike a woman. A gentle, forgiving and thoroughly decent man, he never failed to protect what mattered to him.

Not bad for 1962.

In the midst of all this, my real parents, Sonia and Bruce, were back from the dog-show circuit and living in Sheffield. They would visit on Sunday lunchtimes. I still have the cream-and-brown Bakelite radio set that was on at these occasions. They were always rather strained affairs, leaving me with a lifelong horror of sit-down meals, as well as gin and lipstick. I would push food around the plate and be lectured about not leaving my Brussels sprouts and the perils of not eating food when it was rationed, which of course it wasn’t anymore, but no one could comprehend that reality. The same post-war hangover restricted you to three inches of bathwater, anxiety over the use of electricity and a morbid fear of psychological dissipation caused by speaking on the telephone excessively.

Conversations were peppered with local disasters. So and so had a stroke … auntie somebody had fallen downstairs … teenage pregnancy was rife … and some poor lad had sunk through the crust of one of the many slag heaps that surrounded the pit, only to find red-hot embers beneath, leaving the most horrific burns.

It was following one particular Sunday lunch, when I’d eaten the Brussels sprouts and the chicken formerly wandering about in the garden allotment, that it was time to move on and in with my parents. With my uncle John, I always rode in the front seat, but now I was in the back, staring through the rear window as the first five years of my life shrank away into the distance – then around the corner.

I finally faced forward, into an uncertain future. I could fight a bit, had caught several nasty bugs, commanded my own air force and was pretty close to defying gravity. Living with parents – how hard could it be?