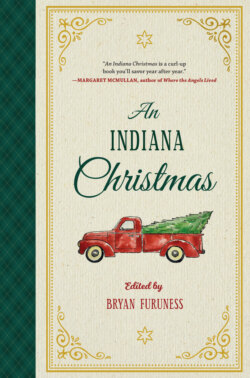

Читать книгу An Indiana Christmas - Bryan Furuness - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

THE OTHER DAY I WAS HAVING COFFEE with Megan from Indiana Humanities. Her organization has a lending library that sends books to reading groups all over the state at no charge. When I told her about this anthology, she said that a book club had just checked out a set of Christmas books.

“Really,” I said.

It was August.

Maybe I shouldn’t have been puzzled. After all, I had passed a happy summer reading Christmas stories and poems and essays for this anthology. I may have been sitting on my deck in a tank top and sunglasses, but in my mind I was tromping through the snow on a Christmas tree farm with Kelsey Timmerman, or riding a horse-drawn sleigh to Jessamyn West’s clapboard house, or standing in a stubbly field with the December barns of a George Kalamaras poem.

Of course, my excuse was an August deadline. Why would a book club choose to read about Christmas in the summer?

Christmas can’t be the sole source of the appeal. If it was, you’d hear Christmas music in July—and to my knowledge, that doesn’t happen.

The appeal must come from the intersection of Christmas and reading. When you cross those wires, you get a strange and powerful synergy.

Picture a deep chair, a soft blanket, a crackling fire, thin branches tapping against a dark windowpane, a Manhattan on the end table, glowing in the firelight like a ruby (I didn’t even mention a book, but you imagined one in your lap, didn’t you?). Forget coziness; this scene evokes a deep contentment. A nested feeling. Hygge, as the Danes call it.

Or picture yourself as a child, on your belly on the floor, paging through a book while music plays low on the stereo and the grown-ups murmur on the couch, someone chuckling, someone stringing popcorn. Now we’re in the territory of nostalgia—for your childhood, or maybe for the childhood you wish you’d had.

Obvious answers, perhaps. But I wonder if the appeal of Christmas stories goes deeper than hygge and nostalgia. Further back than childhood.

You know how sometimes, when you’re drifting off, you suddenly feel like you’re falling? Someone told me this is a vestigial remnant of our old monkey-selves, from the nights we slept in trees and the worst thing that could happen was to fall down to the forest floor where the predators prowled.

This explanation is probably BS. Even so, it’s the kind of BS I like: wrapped in a story, harming no one. It’s like an old myth, the kind the ancients would make up to explain the world around us, to explain ourselves to ourselves. Like the kind of story you tell around a fire with the cold and the dark pressing in all around, which makes you feel like you’re in a diving bell of light and heat. Stories are best when nights are long.

Let’s stay with that image of a fire and all the listeners gathered around. It’s not unlike the nativity scene, is it? A little group, looking inward, huddled together in a vast universe. Christmas is a story of togetherness, a story set and told on a long, dark night.

Picture one more thing for me, and then I’ll let you go to the next fire, the next gathering in this book.

Close your eyes. Imagine yourself falling, back into your past, or into a better dream of your past. When you land, don’t open your eyes. Not yet. Not until you feel warm hands on your cheeks, cradling your face. Not until you hear that voice, the one you thought you would never hear again, say, “Welcome home.”

You’re right where you belong. That’s how you know it’s Christmas.