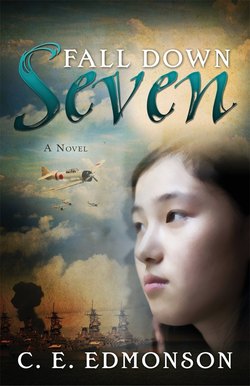

Читать книгу Fall Down Seven - C. E. Edmonson - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеThe day that changed our lives forever started like any other Sunday.

It was December 7, 1941. Our family was up early, as usual, preparing for services at Makai Neighborhood Church. My mom, Akira Arrington, was in the kitchen mixing flour, sugar, buttermilk, and nuts into a batter that would eventually become macadamia pancakes. A bubbling saucepan on the stove held a mix of lychee, mango, guava, and lilikoi that would soon thicken into the compote we’d use to cover the pancakes. All of these fruits and a dozen more grew freely on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, but few of them originated here.

According to my eighth-grade science teacher, Mrs. Koyama, most of the fruits growing wild on the islands had been brought here centuries earlier by explorers. Hawaii being paradise, the fruit trees naturally thrived. Lilikoi, for example, is usually called passion fruit. Native to Brazil, it supposedly got its name from the flower of the vine, which symbolizes the Passion of the Christ. The tendrils represent the whips used against Jesus, the ten petals and sepals represent the ten faithful disciples, the fringe represents the crown of thorns, the three stigmas are the nails, and the five anthers are the wounds.

Okay, I’m doing it again. I’m running off at the pen, just like I’m always running off at the mouth, at least according to my eight-year-old brother, Charlie. I call Charlie “the Whizz.” That’s because the kid never stops moving. At that moment he was in the backyard, throwing baseballs at a mattress propped up against a tree. Behind him the mountains of Oahu soared four thousand feet into the sky.

That early in the morning, the peaks were shrouded by a gray mist that rolled in gentle waves from ridge to ridge. It would burn off in an hour or so, but just at that moment it was pierced by a rainbow that rose from the mist to form a perfect arch before dropping into a narrow ravine. Even by Hawaii’s standards, the rainbow was vivid, its shimmering colors so bright—from the darkest of blues to the darkest of reds—that I had no problem imagining a pot of gold at its end.

My dad, Lieutenant Commander Charles Arrington, US Navy, occupied his usual Sunday-morning place, at least when he wasn’t flying planes from the decks of aircraft carriers somewhere out in the Pacific Ocean. He was sitting on a wicker chair on our back porch—which we called the lanai—reading the Honolulu Advertiser. Dad liked the lanai because it overlooked the Pearl Harbor naval base. Forget the fact that he was on leave and his ship, the USS Lexington, was out at sea. Dad liked to keep an eye on the base at all times because he was in love with flying, and that was where he got to do it. Landing a fighter on the deck of a ship was a fairly new thing at the time, but Charles Arrington was already a veteran. Mostly he trained other pilots.

I was still gazing at the rainbow when Mom put in an appearance. She might have called to me from the kitchen, but I didn’t hear her. When Charlie wanted your attention, he called out in a voice you could hear on the other side of the mountains, but Mom never raised her voice. Born in Japan, she’d been reared in the Japanese tradition, although she’d come to Hawaii with her parents when she was only six and spoke perfect English.

“Emiko, did you put on your dress yet?” she asked.

Obviously I hadn’t. I wore my usual getup: shorts and a cotton blouse. Hawaii is warm all year round—it was seventy degrees on that Sunday morning—and young girls back then were allowed to wear shorts. On the mainland girls mostly wore dresses from the time they were out of diapers. But I was thirteen and rapidly growing past the age when I could get away with shorts. We both knew that.

“It needs to be ironed,” I replied.

“Yes?”

One thing about Mom: although she never directly criticized her children (or anyone else), she could ladle on the guilt. When she was annoyed, she lifted her right eyebrow by way of warning. Ignore this signal and you’d be subjected to a lecture on harmony. Mom was big on obligation to the family and to society in general. Apple carts were not to be upset. To do so would bring shame on the family, and it didn’t get any worse than that. We were encouraged to view everything we did in that light. Would this or that bring shame on the family? If the answer was yes, you didn’t do it. Case closed.

I don’t quite understand how Mom produced two kids so unlike herself. The Whizz never stopped long enough to think about shame or anything else. He was moving through his life at top speed. As for me, girls weren’t supposed to have sharp tongues, not in 1941, and especially not when the mom of the girl in question had been raised in the Japanese tradition. But I had an answer for everything, and I wasn’t afraid to say what I thought. My best friend, Kealani, predicted I’d never find a husband because men don’t like their wives to be smarter than they are. At thirteen years old, I couldn’t make myself care.

Mom’s eyebrow won the debate this time. I fetched the ironing board and iron, and carried both onto the lanai, past the rows of shoes and rubber slippers lined up like military soldiers waiting for inspection. It was like I’d stepped into an alternate universe.

Our house was in the foothills of the Koolau Mountains, and the view from the lanai looked out across the central valley, over the naval base, and into the Pacific. The mountains behind me had checked the mists, leaving pure sunshine to bathe vast fields of sugar cane that swayed in a caressing breeze. The fields ran north from Honolulu and Pearl Harbor, through a central valley that separated us from another set of mountains on Oahu’s eastern edge.

Mainland seasons—winter, spring, summer, fall—don’t mean a lot on Oahu. The temperature’s pretty much the same all year. Hawaii’s year is divided between wet and dry seasons. The wet season begins in November, and that’s when the sugar cane starts to grow. By early December, with the plants about a foot high, their leaves overlap to form a bright-green carpet that stretches as far north as the eye can see.

The green of the sugar cane was offset by the trees on the slope beneath us. The red blossoms on a poinciana tree were crowded so close together that the tree, from above, resembled an open parasol. Just below the poinciana, a little grove of kukui trees clung to the edge of a steep cliff. Their blossoms were as clear and white as the few puffy clouds high above us. Other trees and flowers were even more conspicuous, as if the plant world had decided to run a fashion show. The sweet smell of plumeria and late-season white ginger filled the air, and the dangling, gold blossoms of the shower trees hung from the branches like lace from a bridal gown.

“Are you waiting for the dress to iron itself?”

Did I happen to mention that Mom never uttered a sarcastic word? Did I happen to mention that my dad more than made up for that deficiency? There were times when I wondered how they had ever gotten together. Dad was born and raised in Connecticut, which is six thousand miles from Hawaii, twelve thousand miles from Japan, and light years away from Japanese culture. Charles Arrington was an East Coast Yankee, a man who believed in the old saying “God helps those who help themselves.” By that December he’d flown everything from World War I biplanes to heavy bombers to the fastest fighter planes the country had yet produced. At a time when certain generals predicted that landing an airplane on the deck of moving ship would prove to be impossible, he was out there proving the opposite.

Charles Arrington—Chuck to his friends—was a handsome man by anyone’s standards. Dashing might be a better word. He wasn’t that tall, but to me he was a giant. He had deep-blue eyes and a narrow mustache like Errol Flynn’s in The Charge of the Light Brigade. His mischievous smile reminded me of the Whizz’s grin—or maybe it was the other way around—and his cap bore the golden wings of a naval flyer. But Dad’s attitude was definitely his biggest asset. Failure, he told me too many times to count, teaches success. Don’t be afraid of failure; be afraid of the fear of failure.

“I wanted to ask you something.” I picked up the iron, but then was distracted by a flock of black-hooded mynahs with sun-yellow beaks. They glided over the poinciana to settle, with a flurry of wings and a chorus of harsh squawks, into the branches of a gum tree.

“What were you saying, Emiko?”

“Well, I was just wondering what you’d say if I told you I want to go to college and become a botanist.”

Most women didn’t go to college in 1941 unless they wanted to be teachers. It wasn’t customary. Most girls my age looked forward to marriage and children, not careers. Even when we trained to be nurses or secretaries, we usually gave it up when the babies came along. But Dad had other ideas for me. Mom did too.

“Last week,” Dad noted, “you told me you’d settled on zoologist.”

“Yes, but I think plants are a better bet.”

“And why is that exactly?”

“Because plants are smart enough to keep their mouths shut, and they don’t run away when you try to collect them.”

I loved to make Dad laugh. He wasn’t like Mom, who hid her mouth behind her hand. Dad liked to throw his head back and bray like a donkey. He did that now, much to my satisfaction. I didn’t know it then—even as a faint buzzing registered in my brain—that it would be the last time we would laugh together for nearly four years.

Dad’s head snapped up just as I realized I was hearing the whine of airplane engines—small planes, probably fighters—on the far side of the mountains to the east. Having lived a good part of my life within a few miles of three airfields, I was used to the sound, but there was something off here, something I couldn’t put my finger on.

Dad jumped to his feet. “What is …?” he said, his tone hushed.

I listened to the rattle of a machine gun and heard an explosion in the distance, but I still couldn’t take in the simple fact that the planes weren’t ours. My mind kept saying, No, no, no. Then a torpedo bomber cleared the southern end of the mountains, then another and another and another. To my right, a constellation of black dots grew in size—dozens of planes, each with a single bomb strapped to its undercarriage. They came from the north through the central valley, crossing the fields of pineapple and sugar cane, coming closer and closer until I couldn’t avoid the emblem painted on the fuselage: a big, red sun against a background of white—the flag of Japan. Are we under attack by the Japanese air force?

Mom burst onto the porch. She watched in silence for a moment, then forced back a sob as the Whizz raced across the lanai to wrap his arms around her waist.

“I’ve got to go,” Dad said. “You’ll be fine here. It’s the harbor they’re aiming for.”

The wail of sirens rose from a dozen locations as a line of Japanese pilots—they were close enough for me to see their faces—nosed their planes into long, swooping dives. Their engines were screaming now, the sound painful, as more and more planes—too many to count—followed suit, passing us at more than two hundred miles per hour.

Before me the American fleet—battleships, cruisers, destroyers, minesweepers, and a dozen other vessels—floated alongside Pearl Harbor’s docks, their engines quiet. Just below the harbor the runways of Hickam Field straddled the entrance to the inner bay. Hickam’s runways fed into the Pacific, but no planes moved on them. Jammed close together to prevent sabotage, the planes were sitting ducks for the dive bombers.

I jammed my hands over my ears as the lead plane’s bomb detached and began its long glide toward the huddled aircraft, but my eyes remained open, as if my lids had forgotten how to work. My whole body shook as I watched flames leap from the ground a hundred feet into the air. There were people down there. American soldiers and sailors, civilians too, right inside those flames, right in the heart of those explosions. I opened my mouth to yell “stop,” but the word froze on my lips. This couldn’t be happening. It couldn’t.

When I finally got up the courage to look over at Dad, he was gone. Out on the winding road below, I saw our gray 1938 Ford rushing downhill. A hand touched me, and I jerked away before I realized it was my mother.

“Let’s get inside,” she said.

But I couldn’t move, couldn’t take my eyes away from the slaughter. I watched a long line of torpedo bombers curl around the eastern mountains to approach the harbor from the sea. I watched their torpedoes fall into the peaceful waters of the inner bay, watched them skip over the water before they settled down. Something in me wanted to mark their passage, but the torpedoes were traveling underwater. I could only wait, helpless, until one of our battleships almost lifted out of the water. A few seconds later, the roar of the exploding torpedo reached my ears to blend with the constant explosions at Hickam and Wheeler airfields.

The blasts kept coming after that, so fast I couldn’t keep track even if I weren’t terrified. Within minutes, the harbor and the airfields were covered with an oily, black smoke pierced only by jets of flame as the bombs exploded. The stench of death and destruction reached my nostrils. Still the planes kept coming. Two waves of fighters and bombers, more than three hundred planes, for two hours that seemed more like two years. And my dad was right there in the middle of the fight.

Mom finally came to get me. I remember looking into her dark eyes, as if they might hold an explanation for the insanity, but I found only the need to protect.

“Come inside, Emiko,” she said, taking my arm. “Your brother needs you, and I need you.”

After the Japanese fighters retreated to waiting aircraft carriers, the wail of ambulance sirens replaced the whine of fighter engines. The ambulances ran back and forth between the hospitals over and over again, hour after hour. We could do nothing except choke down the fear that Dad was in one of those ambulances, or that he’d never return at all. It seemed like every ship in the harbor and every plane at the airfields was on fire.

I was inside by then, sitting on a futon with my arm around my brother’s shoulders. Charlie managed to fight back the tears, but his whole body trembled. My mother sat on the other end of the couch, her lips moving, hands folded. Maybe I should have prayed too, but I couldn’t stop looking through the window behind her at the cloud of smoke rising from the harbor, a shimmering curtain of black and gray that only gradually drifted out to sea. When I closed my eyes, I saw the planes again, swarming like insects as they poured down the valley or turned into the harbor, saw their bombs and torpedoes fall away.

Twenty-four hundred Americans died at Pearl Harbor that day. I didn’t know that at the time, but as the fires ebbed and what was left of the fleet came into view, it seemed to me that nobody could have survived the flames and the explosions. Battleships and destroyers and cruisers had sunk to the bottom and turned over. Twisted hunks of metal littered the airfields. Fires continued to burn despite the steady fountains of water pouring from the fire boats. Ten hours later, the ambulances still flew along the streets, from the docks to the hospitals in Honolulu and Diamond Head, ferrying the wounded to overwhelmed emergency rooms.

And still no word from Dad.

Mom, Charlie, and I spent most of the time on the lanai after the Japanese withdrew, peering into the smoke and the chaos as if we could bring Dad home by sheer willpower. Occasionally, a soldier on his way home wandered up the road, his face smeared with soot. Charlie called to them as they passed.

“Have you seen our dad?”

“Who’s your dad, son?”

“Lieutenant Commander Charles Arrington.”

“Sorry, son, I don’t know him.”

Finally, long after dark, when it seemed like I couldn’t stand it for another minute, I spotted the headlights of a car making its way up the winding hill. It stopped in front of our house, and a man got out. The streetlights hadn’t come on that night, and I couldn’t see the car clearly, but something about the way the man walked, with his head up and his shoulders squared, told me who it was.

I grabbed Charlie by the hand and charged out into the street and down the hill. Dad reached out to scoop Charlie into his arms, then took my hand, but he didn’t speak as he led us home. Inside, he put Charlie down and took Mom into his arms. He held her for a long time before he turned his gaze to his children. Dad’s face was streaked with grime, and his blue eyes seemed to reach through me, as if he were staring at something on the far wall and I was as transparent as a window. But I got the message.

Dad would be off to war, and there would be no end to the worrying, the fear that he wouldn’t return. For the next three and a half years, we’d listen to the radio every evening when the news reports came on. We’d listen to the radio and read the newspaper in the morning and watch the newsreels at the movies, like millions of other American families.

There was a difference, though, between the Arringtons and the rest of America. Within a very few days, less than a week, we’d cease to be Japanese-Americans. Somehow, without any discussion at all, we would become Japanese.

We would become the enemy.